- 378 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Publisher

The University Press of KentuckyYear

2011Print ISBN

9780813165820, 9780813133980eBook ISBN

97808131403601

Autumn in the Highlands, 1971

In the final analysis, it is their war. They are the ones who have to win it or lose it. We can help them, we can give them equipment, we can send our men out there as advisers, but they have to win it, the people of Vietnam.

—John F. Kennedy

I went to war in a first-class seat on a chartered, civilian jumbo jet. It was September 1971, and I was an infantry lieutenant colonel going back to Vietnam for my second one-year tour there. The airplane was full of military personnel, and the officers were assigned seats in the first-class section. Sitting next to me was an infantry colonel, an army aviator, who introduced himself as Robert S. Keller. He was going to be the senior adviser to the 23rd ARVN Infantry Division. I was going to be the G-3 (operations) adviser to that same division. Colonel Keller would be my commanding officer.

The 23rd ARVN Infantry Division was under II Corps in Pleiku, so after a couple days of personnel processing and orientations in Saigon I moved on to Pleiku for more processing and some briefings by the II Corps advisers in the large American military compound in Pleiku. Transient officers staying overnight were assigned to individual “hooches” in a row of identical small buildings. As I was walking across a big lawn, returning from dinner one beautiful evening, someone’s radio was tuned to the Armed Forces Network (AFN), and Joan Baez was singing “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down.” Just as she sang “See there goes Robert E. Lee,” there was the heavy CRUMP! CRUMP! CRUMP! of mortar rounds falling in the compound. A siren wailed, and I ran to the nearest bunker. Welcome back to Vietnam!

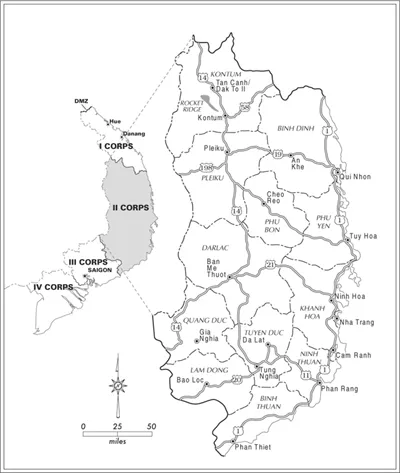

II Corps: major cities, highways, and boundaries of provinces. Small inset map shows the position of II Corps within South Vietnam.

During my first tour in Vietnam, I learned that when you live with intermittent incoming artillery or rocket fire, you become somewhat used to it. To me, the US Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (MACV) compound at Pleiku seemed less dangerous than trying to cross a busy street in Saigon. However, Brigadier General George E. Wear, the II Corps deputy senior adviser, saw the reaction of high-ranking visitors to II Corps headquarters:

The area containing the US Advisory compound [Pleiku Barracks] [and] the II Corps headquarters building with adjoining ARVN living quarters was the prime target for 120-mm rockets. They didn’t do much damage unless a direct hit. We were rocketed on an average of about every two weeks or so during the 20 months I was there. Occasionally, a direct hit would produce US or ARVN casualties. We could tell when the first rocket landed whether they were going to be a problem. Alarms were sounded, artillery fired in the general direction of the launch sites, and we went on about our business. If they started landing during dinner, we usually kept on eating.

I realized near the end of my tour up there that not a single [visiting] full colonel or higher ever spent a night [in Pleiku] in all the time I was there. Colonels and generals would show up during the day for some reason or another and then would quickly depart.1

By 1971, many of the American and South Vietnamese military and pacification experts thought the war was won. However, the South Vietnamese had reached the limits of what they could do to defend themselves, and our government had reached the limits of what it would give them to do it. The North Vietnamese were unfortunately willing to intensify their struggle for final victory, and massive aid from China and the Soviet Union would give them the means to do it.2

As we withdrew from Vietnam, our government’s attention was turning toward other places and other problems. Even the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) was paying less attention to Vietnam. It published a national intelligence estimate on Vietnam in April 1971 and did not publish another one until October 1973, 18 months later.3 The media were also turning away from Vietnam. War news was disappearing from magazine covers, the front pages of newspapers, and TV news programs.

At the peak of our involvement, there were 543,400 Americans in South Vietnam.4 We took over the war, and many of the South Vietnamese military units were relegated to guarding government installations and hunting down local Communist forces while the Americans went into the jungle to seek big battles with the NVA.

The American people and Congress were increasingly opposed to continued involvement in Vietnam, and there was no chance this trend would be reversed.5 US troop strength there was now less than 100,000 and falling fast. Most of our allies’ forces were already withdrawn, and world opinion generally did not support our efforts in Vietnam. Some Western governments were even supporting our enemies. In May 1971, Swedish foreign minister Torsten Nilsson announced that Sweden was expanding its assistance to the VC with an initial donation of $550,000 worth of medical supplies and hospital equipment.6

President Richard M. Nixon’s claim that he had a plan to get us out of Vietnam was a major factor in his election in 1968. After his inauguration, he revealed the plan as “Vietnamization”—to turn the war over to the South Vietnamese. He started withdrawing American troops while building up the South Vietnamese government and armed forces. The North Vietnamese said the purpose of Vietnamization was to change the color of the corpses.7

General William C. Westmoreland, the MACV commander, returned to Washington to become chief of staff of the army in July 1968. He was replaced by his deputy, General Creighton W. Abrams, who was given the responsibility of withdrawing his US ground forces while building up the South Vietnamese forces. When Nixon took office, there were about 850,000 troops in South Vietnam’s armed forces. This number was soon increased to more than a million, and the Americans replaced the South Vietnamese’s World War II–era weapons with the same weapons used by the US armed forces. More than a million M-16 rifles, 12,000 M-60 machine guns, 40,000 M-79 grenade launchers, and 2,000 artillery pieces and mortars were given to the Vietnamese. They also received new tactical radios; 46,000 vehicles, ships, and boats; and 1,100 helicopters and other aircraft.8

The Americans created ARVN in their own image as much as possible. The organizational structure, equipment, ranks, supply system, and personnel system were almost exact copies of those in the US Army. Starting with the smallest element, ARVN had infantry platoons of about 30–40 men and infantry companies of 150–200 men in four platoons and a headquarters element. There were three or four companies in a battalion, and three or four battalions in a regiment. The configuration varied by division, and the 23rd ARVN Division had three companies per battalion and four battalions per regiment.

The ARVN artillery batteries, armor companies, and armored cavalry troops had fewer men than similar infantry units, but they were also organized in battalions—or squadrons for the cavalry. An ARVN infantry division also had an artillery regiment consisting of three artillery battalions with 105-mm howitzers. Each infantry regiment had two 81-mm mortars, and each infantry company had two 60-mm mortars. ARVN was plagued by desertions, so most units had fewer men present for duty than was authorized.

The South Vietnamese also had the Airborne Division and Ranger battalions in Ranger groups. They were moved around the country like chess pieces to block enemy threats or to plug holes in the defenses. In addition, Border Ranger battalions were manning static bases along the border. Most of the troops in Border Ranger battalions were from local ethnic groups, like the Montagnards, but most of their officers were Vietnamese. The Border Rangers did not receive the same training as the regular Ranger battalions, and they were not moved around the country to deal with military emergencies.

Regional Forces (RFs), or “Ruffs,” were recruited in each province. The RFs were organized like ARVN units and were under the command of the province chiefs, most of whom were ARVN officers. They could be deployed anywhere in their home province but were seldom sent to other provinces. They were as well armed—including their own artillery—and almost as well trained as the ARVN units. Popular Forces (PFs), or “Puffs,” were also recruited in each village. These forces had the same small arms as ARVN or the RF, but they stayed near their homes and guarded local bridges, government buildings, and their own villages.

The Ruff Puffs had more men under arms than all the regular forces combined. Under the upgrading program started by General Abrams, they had a higher priority than ARVN for new equipment, such as M-16s. They were able to defend against the local VC and even launch limited operations against them, but they lacked the logistical support required to spend extended periods of time in the field. They were not able to engage in lengthy battles with the NVA. Although the Ruff Puffs and civilian police guarded much of the government infrastructure, some of ARVN’s manpower was also committed to guarding government installations—including its own camps—and to clearing roads of mines and ambushes.

Included in the change of direction under General Abrams was a campaign to retrain the South Vietnamese armed forces. More than 12,000 ARVN officers were sent to the United States for advanced training, and 350 five-man teams of American advisers were sent to train the RFs and PFs on their new weapons.9

Because the Americans were withdrawing and the South Vietnamese were being strengthened with new weapons and training, General Abrams considered the advisers essential to his effort to turn the war over to the Vietnamese, and he wanted to improve the quality of the officers selected for adviser assignments. In early 1970, Abrams told Secretary of Defense Melvin R. Laird and chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General Earle G. Wheeler that he was “actively shifting talent from U.S. units into the advisory thing. We’ve got to dig in there and get some blue chips out of the one bag and stick them in the other.”10

The advisers had varying degrees of rapport with and success in dealing with their Vietnamese counterparts. If the ARVN officer did not speak enough English or the American officer did not speak enough Vietnamese—and few did—then they had to communicate through an interpreter, which further complicated their relationship and ability to get anything accomplished. The basic technique was for the adviser to tell his counterpart what he recommended and tell his American superior the same thing. The other American adviser would then tell his counterpart, who would tell his Vietnamese superior or subordinate. When that system worked well—and that did not always happen—the ARVN counterparts would receive orders from their superiors that paralleled their advisers’ recommendations.

The advisers and their counterparts often had a difficult relationship. In addition to the language and cultural differences, the advisers were often younger and sometimes lower in rank than their Vietnamese counterparts. In the early 1960s, the American captains and lieutenants advising ARVN battalions and companies in the field were on their first tour in Vietnam. Few of them were old enough to have experienced combat in Korea, but they were advising men with years of combat experience, sometimes going back to serving with the French against the Viet Minh ten years earlier. In those circumstances, the advisers tended to concentrate on equipment and logistical matters. However, after the mid-1960s, when US involvement surged, the advisers became their counterparts’ link to vital US helicopter airlift, artillery and tactical air support, and B-52 strikes. The relationship became much closer then. In December 1968, at the height of the war, 11,000 American advisers were working with the South Vietnamese armed forces.11 By the time the last US advisers left Vietnam in early 1973, many ARVN officers had worked with as many as 20 to 30 different advisers.12

South Vietnam had its own air force, the South Vietnamese Air Force (VNAF). The performance of VNAF’s A-1 and A-37 fighter-bomber pilots was excellent, and its AC-47 gunship and C-123 cargo aircraft crews were almost as good. VNAF fighter-bomber pilots were more experienced than the Americans, and after years of bombing in their own country, they knew the territory. However, both the Americans and the South Vietnamese held VNAF helicopter crews in contempt. The only exception was the crews of VNAF helicopter gunships. ARVN had no helicopters of its own; they all belonged to VNAF, and VNAF was a separate service with its own chain of command. VNAF troop-lift helicopter units were seldom responsive to ARVN officers, and their support for ARVN was notoriously poor.

VNAF helicopter pilots sold rides to unauthorized civilians, charged refugees for evacuation flights, and sometimes sold their equipment on the black market. Whenever we were flying in a VNAF helicopter without seat belts or doors and with a VNAF “cowboy” pilot at the controls, I maintained a tight grip on some part of the interior frame and hoped for the best. How well the engines were being maintained was also a worry. If we informed our ARVN counterparts that our helicopter support for a mission was coming from VNAF rather than from a US unit, we could see disappointment and even fear in their eyes. ARVN soldiers could see the stark contrast between VNAF pilots and the US helicopter pilots who risked their lives to resupply and evacuate advisers. VNAF helicopter pilots had a bad reputation for refusing to fly medical evacuation (medevac), troop transport, or resupply missions if they might encounter hostile fire.

VNAF medevac pilots sometimes refused to pick up ARVN casualties in the battle area. Their medevac pilots would even hover four or five feet off the ground, ready for a fast getaway but so high only the walking wounded could get onboard. The advisers were ordered not to call for a “dustoff” (an American helicopter medevac mission) unless there was an American casualty because the USAF advisers with VNAF were trying to force ARVN commanders to put pressure on VNAF to do its job. We complied, but it was hard to tell a counterpart that we could not call for a dustoff to pick up his wounded men and that he would need to use his chain of command to complain about VNAF so they would be forced to do their job.

On paper, the South Vietnamese armed forces looked impressive, but, as with many military organizations, the actual strength present for duty was usually less. The II Corps commander, Lieutenant General Ngo Dzu, visited the 23rd Division one day and invited the division commander, Brigadier General Vo Vanh Canh, Colonel Keller, and me to join him for an informal lunch at a local restaurant. General Dzu told us that a few weeks earlier he and another ARVN general ate lunch in a civilian restaurant. When Dzu had asked their waiter, a young man of military age, why he was not in the army, the waiter told them that he was in the army, but that his company commander allowed him to work full-time as a waiter as long as he split his civilian wages with the commander. This pra...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Maps

- Preface

- Prologue Kontum: Now and Then

- 1. Autumn in the Highlands, 1971

- 2. Fighting in Phu Nhon

- 3. A Hundred Tons of Bombs

- 4. The Looming Threat

- 5. The Year of the Rat

- 6. The North Vietnamese Invasion

- 7. Attacking in An Khe Pass

- 8. Our Firebases Fall

- 9. The Collapse at Tan Canh

- 10. A Debacle at Dak To

- 11. A New Team for the Defense

- 12. Closing in on Kontum

- 13. Cut Off and Surrounded

- 14. Tanks Attacking!

- 15. Struggling to Hold It Together

- 16. “Brother, This Is Going to Be It!”

- 17. “You Are Going to Be Overrun”

- 18. The Dirty Job of Killing

- 19. All Over but the Shooting?

- 20. Finishing the Job

- Epilogue: The End of the Fight

- Acknowledgments

- Glossary: Abbreviations and Military Jargon

- Notes

- Selected Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Kontum by Thomas P. McKenna in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & 20th Century History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.