- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Crawfish Bottom by Douglas A. Boyd in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

The University Press of KentuckyYear

2011Print ISBN

9780813144337, 9780813134086eBook ISBN

9780813140124Chapter One

The “Lower” Part of the City

Very few documentary records exist that allow us to interpret the earliest periods of the neighborhood known as “Craw” or “the Bottom,” the poorest section of Frankfort. However, existing sources suggest that from its inception Craw captured and sustained the Frankfort public’s fascination. Few academic historians have written about Craw, and those who have rarely expand beyond brief, tangential references, and primary sources are rare. The relatively few existing newspaper accounts that reference Craw mostly chronicle crime, violence, flooding, rampant alcohol use, and poverty. Nevertheless, this small corpus of early newspaper references and articles contains crucial sources for setting up the historical context and interpreting Craw’s earliest years.

Since the neighborhood is no longer physically available for analysis, this chapter chronologically and thematically examines the trajectory of Craw’s life and death by reaching back to a memory embodied no longer in human persons, but in print, exploring this neighborhood between the time of its birth in the early 1870s and the first premature declaration of its demise in the shadows of Prohibition in 1918. In this period, the “lower” part of the city of Frankfort first began to demonstrate the characteristic traits that would eventually define it and serve as rationalizations for its reform and eventual destruction. During the 1870s, Frankfort newspapers provide the earliest historical references to the neighborhood as “Crawfish Bottom,” “Craw,” or “the Craw.”1 The use of these distinct tags by the city’s news organizations demonstrates emerging patterns of meaning inextricably linked to these unofficial, vernacular terms representing this neighborhood.

THE LOWLANDS

The neighborhood occupied fifty acres of low-lying land along the Kentucky River. In 1897, local historian Jennie Chinn Morton described the land that eventually became Craw as having once been a racecourse for training horses and grounds for circus shows.2 In celebration of Frankfort’s centennial in 1886, a local newspaper, the Capital, conducted several interviews with longtime local citizens and printed their reminiscences of Frankfort. The eight pages of this special edition present some of those interviews, which offer a few clues about the early days of the land that would later be called “Craw.” Residents described this section of town as unsuitable for building, due to the regularity of flooding by the Kentucky River; one noted that when General James Wilkinson was stationed there in 1795–1796, the land was a “pond of stagnant water.” Wilkinson reportedly dug ditches to drain the land “so as to very much improve the premises, and destroy the noxious effluvia, thereby preserving the health of the citizens.”3 Captain Sanford Goins narrated his childhood memories of Frankfort during the 1820s: “What today is so well known as ‘Craw’ was a large lake or pond of water.”4

Prior to the Civil War, settlement in Craw had remained relatively sparse. In 1851, the legislature voted to move the gas works from the northwest corner of Capitol Square to the corner of Mero and Washington streets. However, the effects of the emissions—“the most villainous compound of foul scents”—proved to be more severe than city officials expected.5 The legislature subsequently declared the gas works a “nuisance” and moved it to the edge of town, what would later become Craw.

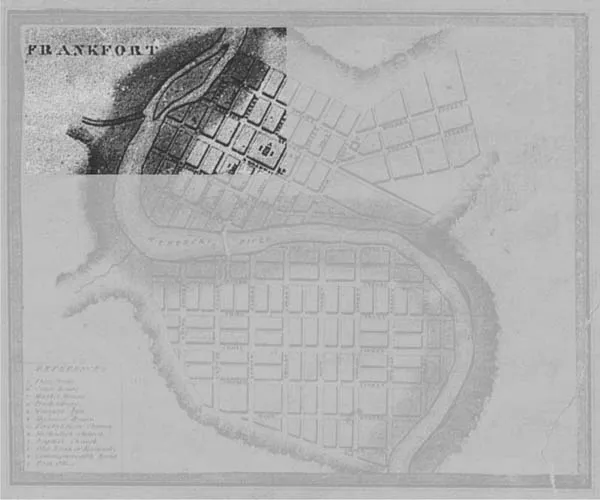

Frankfort in 1796 as depicted on the map “Road from Limestone to Frankfort in the state of Kentucky.” Plate #22 from Georges Henri Victor Collot’s Voyages dans l’Amérique septentrionale, 1826. The map was drawn in 1796 but not published until 1826. Courtesy of W. S. Hoole Special Collections, University of Alabama Libraries.

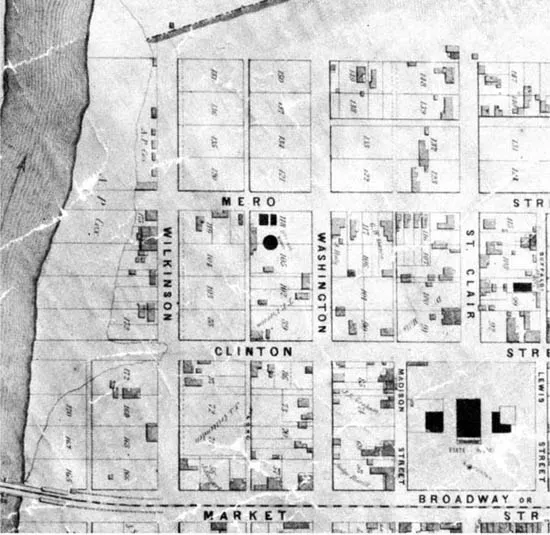

The neighborhood in 1818 as depicted on the map “Kentucky: Reduced from Doct. Luke Munsell Map 1818 and 1834—Inset of Frankfort” (as indicated by added screening). Courtesy of the Kentucky Historical Society.

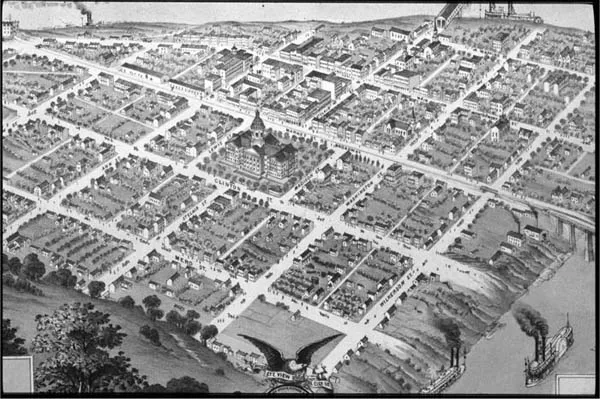

According to available maps and images of Frankfort, the two vacant blocks of the northwestern part of town remained mostly vacant until the 1870s. The 1854 Hart and Mapother map of Frankfort (see page 18) shows the northwestern-most block, then framed by Wilkinson and Mero streets, almost completely vacant, although occupation of the blocks adjacent to Fort Hill increased to the east, away from the river. The Hart and Mapother map does show some settlement along Fort Hill, but Hill Street still lacked municipal sanction. The 1871 Birdseye map of Frankfort (see page 19) visually supports this development pattern, with the viewable city blocks nearest the river in the northwest corner still relatively vacant.6 In the early 1870s, rapid development of the land to the north of Mero Street formed the Hill Street blocks of Craw on the tracts of land adjacent to the steep wall of Fort Hill on the north, and the 1880 census reveals the civic creation of Hill Street adjacent to Fort Hill.

The neighborhood in 1854 as depicted on the map “The City of Frankfort, Franklin Co. KY: Hart and Mapother Map, 1854.” Courtesy of the Kentucky Historical Society.

The 1882 Frankfort atlas visually displays dwellings on each tract of land on the south side of Hill Street between Wilkinson and St. Clair streets. The Frankfort city directory for 1884–1885 demonstrates Hill Street’s development, with dwellings appearing mainly on the south side of the street, from the river to the workhouse; by the mid-1890s the development of dwellings had reached capacity on both sides of the street. The atlas also confirms the rapid settlement of all three east-west blocks north of Mero Street moving away from the river in the early to mid-1870s.

Northwest Frankfort as depicted in “Birdseye View of the City of Frankfort the Capital of Kentucky, 1871.” Courtesy of the Kentucky Historical Society.

According to historian Carl E. Kramer, the Civil War’s end brought the arrival of former slaves to Frankfort, seeking homes for their families. The land in Craw was inexpensive, so between 1865 and 1880 construction commenced on humble dwellings for rental to blacks—always a slight majority—and poor whites.7 The evidence clearly demonstrates a population explosion in the neighborhood in the years following the Civil War. Frankfort’s African American population grew from 1,282 in 1860 to 2,335 in 1870—an 82.1 percent increase. Between 1870 and 1880, the black population rose from 2,335 to 3,199, representing another 39 percent increase.8 The 1880 census lists 173 “colored” residents and only 18 white residents living on Hill Street. The 1884–1885 Frankfort city directory lists 69 percent of the households in Craw’s core boundaries as “colored.” Craw also housed a large portion of Frankfort’s immigrant population, predominately German and Irish. The 1884–1885 directories list professions among the black population as diverse as teachers, Capitol Hotel waiters, porters, drivers, and general and domestic laborers. Among the white populace in Craw at the time, occupations included mainly general laborers, those who worked in the nearby river mills, and a few policemen.

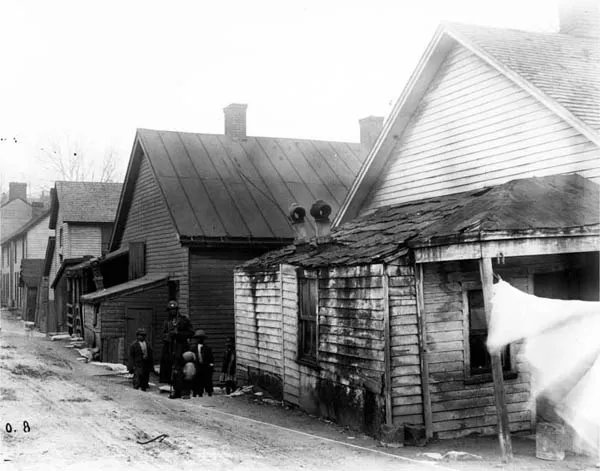

(Above) Early photo of the neighborhood from the “Slums of Frankfort” series. Photograph no. 3, 1913, Wilkinson Street. Courtesy of the Kentucky Historical Society.

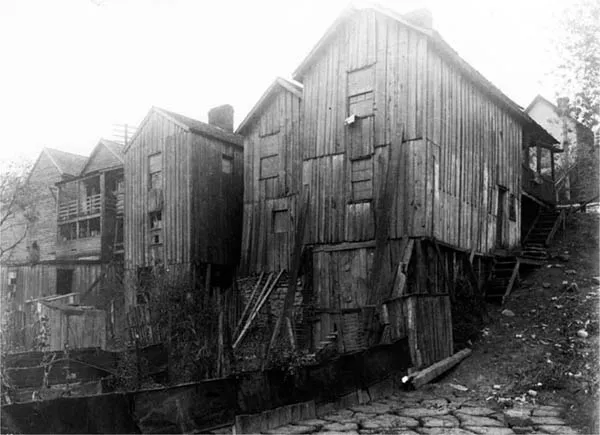

(Below) Early photo of the neighborhood from the “Slums of Frankfort” series. Photograph no. 8, 1913. Courtesy of the Kentucky Historical Society.

At different times in history this neighborhood possessed many labels that conveyed varying sets of meanings and associations to different groups of people. In the years immediately following the Civil War, newspapers still referred to this part of town as the “lower part of the city.” “We regret to learn,” one newspaper reported in 1876, “that a portion of the inhabitants of the lower part of the city, near the foot of Clinton and Mero street, were in some danger of having the lower stories of their dwellings invaded by the rising freshet.”9 Also during the 1870s, Frankfort newspaper articles began to call for the implementation of municipal improvements for the “lower” part of town. Public requests for improvements focused mostly on the lack of street lighting and the poor condition of the area’s sidewalks and roads. One 1877 article complained, “The darkness back of Mero Street, even on moonlit nights is almost impenetrable.” In addition to noting the street’s bad sidewalks and dangerous crossings, the article suggests that “a few lamps, distributed with good judgment, would help that part of the city very materially.”10 Another article that year stated that in order to fully appreciate darkness, one should travel “beyond Mero Street . . . after nightfall when there is no moon.11 “Beyond Mero Street” referred to the newly populated Hill Street block between Fort Hill and Mero Street, primarily inhabited by African American families in the 1870s and 1880s.

Fish Trap Island in 1818 as depicted on the map “Kentucky: Reduced from Doct. Luke Munsell Map 1818 and 1834 (Inset of Frankfort).” Courtesy of the Kentucky Historical Society.

Early photo of the neighborhood from the “Civic League” series. “Exterior of Residences,” 1913. Courtesy of the Kentucky Historical Society.

Earlier in the 1870s, newspaper articles had also begun to associate this part of town with the less-desirable elements of society: “Sabbath Desecration—We are requested to call the attention of the proper officers of the city to the fact that a motley congregation of a hundred or more boys and men, white and black, assemble every Sunday on the sandbar, in the rear of Scott’s tenement houses, on [the] Kentucky river, within the city limits, where they shamefully desecrate the Sabbath, and horrify all decent people by shouting, racing, swearing, gaming in many ways, and committing all manner of acts of Satanic deviltry.”12 John L. Scott’s tenement houses on Wilkinson Street, between Mero and Clinton, behind which such offenses occurred, backed up to the river just above Fish Trap Island, otherwise known as “the sandbar.”13 In the early years of Frankfort, “an assortment of snags, sandbars, rock shoals, [and] submerged islands” made the Kentucky River very difficult to navigate.14 Fish Trap Island, a significant obstacle to river navigation at that time, measured nine hundred yards in length and rose sixty inches above the water.15 Its size and its relative isolation from the rest of the city made it a semiprotected place in which to violate civic and moral virtues. In addition to civic sins like gambling, and religious sins like “Sabbath desecration,” reports of violent crimes within the confines of the “lower” part of Frankfort also became more prevalent. One 1875 article reported three “culled gentamen” who had been placed in the “cooler” for a violent confrontation that had broken out in “the lower part of the city.”16

Early photo of the neighborhood from the “Civic League” series. “Views in Poor Settlements/Black Family in Front of Residences,” 1913. Courtesy of the Kentucky Historical Society.

In or around 1877, this part of town earned a more specific name, distinguishing it from the rest of Frankfort, as the city’s newspapers less frequently used generic, spatially oriented terminology to describe the area. A February 1877 article in the Weekly Yeoman reported that “Esquire McDonald investigated a breach of the peace among some colored folk from ‘Craw-fish Bottom.’”17 In August 1877 a piece announced that “the Alcalde of Craw Fish Bottom has recovered from the effects of a splinter, and is now on post.”18 That year the same newspaper also reported that “some of the co...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Series Editors’ Foreword

- Foreword

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Reputation as History

- 1. The “Lower” Part of the City

- 2. Defining Craw

- 3. Contesting Public Memory

- 4. The Other Side of the Tracks

- 5. The King of Craw

- Conclusion: Remembering Craw

- Notes

- Selected Bibliography

- Index