- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

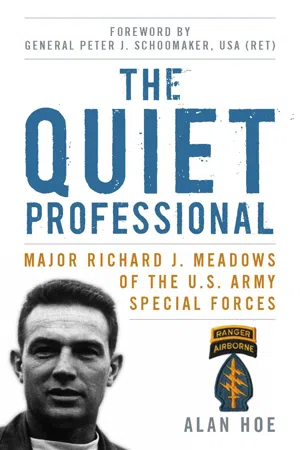

Yes, you can access The Quiet Professional by Alan Hoe in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military & Maritime History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

The University Press of KentuckyYear

2011Print ISBN

9780813144511, 9780813133997eBook ISBN

97808131403391

The Early Years

1932–1947

In the early 1930s America was still in the grip of the economic depression which was to last almost until the decision to enter World War II in December 1941. Nowhere was this worse than in the valleys, forests, and mountains of West Virginia. The state lagged well behind the national average in respect to personal income and overall development. One of the reasons for this is a freak of nature. West Virginia is well-named the “Mountain State,” for almost the whole of it is part of the great Appalachian mountain range.

The earthquakes that formed the Appalachians gave West Virginia two important features. First, the small valleys and, lower down in the foothills, large flood plains are all richly fertile. Second, those tectonic plate collisions exposed some of the heaviest soft coal deposits in America. The majority of the state’s labor force was thus divided between farming and mining. The mountains also locked the folk into small communities in the narrow valleys, where family farms sprang up in the “hollows” along the creeks and rivers.

However, nature mainly benefited the wealthy and powerful who were able to purchase huge tracts of land and exploit the ready supply of cheap labor. They were able to control local commerce through company-owned stores and the application of credit lines to coal workers and small farmers alike. Coal was expensive to transport; therefore, many light industrial factories were established close to the source of power. The result was a sprawling mess of coal camps and factories spewing out the smoke and grime which choked the atmosphere and lent an air of gloomy despair to the once beautiful valleys.

In some ways the character of the West Virginians worsened the situation. Mountain dwellers throughout the world tend to be fiercely independent and inward looking. In West Virginia much of this spirit can be ascribed to the Celtic characteristics of the many Scots and Irish who settled the more inaccessible areas in the 1700s. This history is still detectable today in the speech patterns, musical instruments, ballads, and handicrafts of the area. These people were staunch unionists who refused to accept the Secession Convention in 1861, and in 1863 the new state of West Virginia was accepted into the Union. Tightly knit communities meant that few people looked outside the state to compare their way of life with that of others more affluent. A condition of hopeless acceptance was reached. Some youngsters left the state in search of work, but in the main, the West Virginians of the 1930s divided into three categories. Some eked a living from family farms, some opted for the rigors of the coal camps, and a small percentage lived on the proceeds of bootlegging.

The farmers had chosen a hard life. The rugged terrain made workable land plots small and their priority was to feed their families. Meat was plentiful for the hunters, and many became expert backwoodsmen. White-tailed deer, rabbits, squirrels, and groundhogs were in good supply, along with some of the finest trout fishing in the South. The vegetables and fruit left over after the family had been fed would be sold on the sidewalks in the small towns or bartered for commodities in the few independent stores. Money was scarce. There were slim pickings from these sales. Life was a matter of subsistence, with little money left over for luxuries.

The men who elected to work in the coal industry had an even harder life. This was coal mining at its most basic, and little attention was paid to safety. The coal camps were no more than shantytowns. A gritty black dust penetrated every crack and crevice of the company-owned shacks. The owners of the mines kept a tight grip on their labor force through cleverly imposed debts. What finer way to keep a man bound to the coal faces than by holding his “mark” against groceries and clothing bought at the company store on onerous credit terms: “Saint Peter don’t you call me ’cause I can’t go / I owe my soul to the company store.”

Life was hard and often short. Those who did not die in accidents at the coal face stood a fair chance of succumbing to “black lung” disease (pneumoconiosis), caused by the constant inhalation of the fine, pervasive dust. Conditions were so bad that six times in its history the coal mining areas of West Virginia had been subjected to intervention by the National Guard, which was used to quell riots. In the early 1930s the miners won the right to organize labor unions, but it took years for conditions to improve significantly.

Declare something illegal and it becomes more attractive. The National Prohibition Act of 1919 increased the value of bootleg corn liquor. There were those who risked life and freedom to make a living from moonshine whiskey. Many of the farmers indulged in it as a sideline to supplement their meager incomes. Even after prohibition ended it remained illegal to distill without a license, but the mountain men of West Virginia perfected the art of evading the ever-vigilant revenuers.

This was the West Virginia into which Bernard J. Meadows Jr. moved in 1938. Before this transfer the Meadows’s lifestyle had been very basic but on a par with their neighbors in the Allegheny country, where Junior had been born six years earlier. Bernie Meadows Sr. scraped a living as best he could working in the coal camps and supplementing his income by selling moonshine. Junior’s memories of that part of his childhood were vivid and mixed. There were hard times with an always belligerent and often violent father who was prone to taking a little too much of his own illegal brew. His mother, Hattie, suffered as much if not more than Junior at those times.

It is a strange thing that humans sometimes remember more easily the good times than the bad ones. Junior readily appreciated the love and affection that he found within the home of his grandparents, John W. and Fanny Booth. During Bernie Senior’s many absences at the coal camps Junior spent much of his time with John and Fanny. A memory that stayed with him typifies the warm relationship. One of his childhood pleasures was lying in bed in the biting, pre-dawn cold and hearing Grandpa Booth get up to light the fire. The smell of the wood smoke from the potbellied stove would slowly permeate the house as he huddled into the comforting warmth of his rough blanket. Reluctant to face the dawn chill, he strained his ears for a familiar sound. One of his grandfather’s early morning habits was to heat the water for his first hot toddy of the day. The tinkle of spoon against glass was the signal for Junior to rise. Still wrapped in his blanket, he would climb onto his grandfather’s knee, where he would enjoy the treat of being handed the glass and spoon to scoop out the warming residue. In Meadows’s own words: “It was a purely private time. Grandpa would put his arm around me and begin to tell stories as I enjoyed the taste of sugar and the remains of the warm whiskey. He was a gentle man and still had a British accent—forever telling jokes against the Irish in that very precise way of speaking that he had. Those were some of the happiest times of my childhood.”

Junior was a shy boy, which was natural enough considering his environment. The community was very small and strangers were unusual in the hollows (sometimes they would be revenuers looking for moonshine stills), and so the family was his main experience of the adult world.

He remembered the happy days spent with Grandpa Booth. Though his clothes were poor, usually hand-me-downs, his food was wholesome. There was a wild aspect to the life that appealed to him—the days were spent hunting squirrels, deer, and turkeys. He would catch crawdads to bait his raccoon traps—raccoons being considered good food. In the evenings, before the advent of the radio, the family would gather on the veranda to tell tales and sing.

Meadows did not build a close relationship with his older sister, Verna Lee. She moved everywhere with her mother, and so they met only on those occasions when Meadows spent time at whatever place his mother was. In later years, Verna Lee would be of great assistance to her brother.

Meadows did not have a good relationship with his mother, and his happiest months were spent with the Booths. There was no way to get a good living from the farms, but at that age Junior had no need of money. Most of the Meadows and Booths (the maternal side of the family) were moonshiners, and the competition to produce the best corn liquor was fierce. Both families had a reputation for making a fine drink. They made their own special brew with peaches and apricots. Straight corn liquor could fetch around $8 a gallon then, but the peach and apricot “brandy” was good for about $15. All the family drank on those evenings sitting on the veranda, “porching” as they called it. The liquor would make the songs and stories more prolific, and in the flickering glow of the kerosene lamp the screeches of the bobcats and cries of the whippoorwills created an eerie atmosphere. The arrival of the radio, known locally as the “squeaky box,” rather changed that way of life.

When not with his grandparents, Junior lived in a company-owned shack in one of the coal camps. It was a far cry from Grandpa Booth’s home at Johnson’s Creek. The atmosphere was violent. The frustration of the miners in never being able to get financially ahead of the owners due to the enforced credit system and meager wages led to drunkenness and fighting. Bernie Meadows, tough and violent himself, was never far from the action. In Junior’s words:

Nothing was ever so true as the lines from the song, “I loaded sixteen tons and what did I get? Another day older and deeper in debt.” Life was pretty tough until the day Dad said: “To hell with this. No more coal towns.” In truth he’d just had his still busted up by the law for about the thirtieth time and he’d been told by the deputy sheriff to get out of West Virginia or die. That deputy meant it too. Dad often told me that the deputies would take all the moonshine back to the jailhouse to destroy it, but the quality was so good that usually they drank it or sold it themselves. Anyway, soon after that he moved on and got himself a job in the coal mining company at Besoco. That was all he could get in spite of saying “no more coal towns.” Somehow he eventually raised enough money to lease about one hundred acres of farmland—he was always a country boy at heart and never a true miner. He sent for Mom and me, and a lot of the Booths and Meadows clan followed us.

He bought some stock. A cow, some chickens, ducks, and a horse and life was pretty good for a while. We were into the foothills of the mountains and the moonshine stills were set up again, but this time Dad wasn’t a part of it—he never brewed another drop as far as I know. I didn’t mind that one little bit—I’d spent too many hours at one end of a crosscut saw turning out cordwood for the stills. This was the biggest give-away to the revenuers. A moonshine still burns up a whole heap of wood in a short time and they’d look for piles of cordwood or places where the moonshiners had been felling and know they were in the right area. Sometimes we hauled timber for what seemed miles to cut down the odds of discovery. When Dad’s moonshining days came to an end it was because his sentry fell asleep and got himself whacked over the head. Good military lesson there. He might have stopped brewing but he sure as heck didn’t stop drinking the stuff.

Junior was turning six years old when he started his formal education, though life was far from settled. His mother and father were going through a bad patch; separations were frequent and often violent, and Junior saw Hattie only occasionally. The farm didn’t work out and Bernie Senior was forced to keep returning to the Besoco coal camps he hated. Junior spent much of his time with his grandparents. Often his father would return from Besoco to try to take him back, but Junior would usually manage to hide out in the woods until he left. Aware of his own tendency to violence when he was drinking, Bernie Meadows went through long periods of abstinence, but these were not peaceful times as he then became prone to bouts of religious mania that were as disturbing as his drunkenness. Junior felt sorry for his father, but he just couldn’t face the move to the coal camps again or the atmosphere at home. During the school vacations and on weekends he was hired out as a farmhand (he received none of the pay himself). He did not like farming: “It always seemed to me that more work went into maintaining the horse than the horse put into the farm.” His family had thought that he should become either a farmer or a builder, but to Junior life was much sweeter hunting groundhog than “pulling corn” or “laying planks.”

Those halcyon days in the mountains were responsible for the real birth of the “point man.” The writer who captured Junior’s imagination was Zane Grey. One of his heroes in particular was the legendary Louis Wetzel, intrepid hunter of the Huron, Shawnee, and Delaware Indians, who inhabited the forests bordering the Ohio River. The woodlands of the Virginias provided a living theater within which Junior could reenact the stories of the frontiersmen. The young warrior, now (in his own mind at least) the very reincarnation of Louis Wetzel, was to carry out many a daring mission as he stealthily took himself foot by careful foot through the undergrowth. Not a leaf would he disturb, not a branch would he shake as he closed with his deadly foe. All the odds were against him in these Indian-infested forests, but, dammit, he was going to win through. Zane Grey’s characters were not the only examples to him in the art of fieldcraft. Grandpa Booth and Uncles Oscar and Henderson, all hard-muscled men of whipcord strength, were also accomplished hunters eager to pass on their skills to such a willing youth. He learned well lessons that would never desert him.

A boy given these surroundings and home life either uses his imagination or develops into a dull and uninteresting individual. Junior let his thoughts run rife as he invented secret and dangerous missions for himself. A squirrel would become the dreaded Silver-tip, chief of the Shawnee nation and arch enemy of Wetzel. After a long stalk it would be dropped with a single shot to the head. Sometimes he would be Wetzel, sometimes Colonel Zane or maybe even Major Sam McColoch bent on doing good for his country. Whatever the self-imposed mission, it is apparent that the frontiersmen of legend and book really lived in the mind of the young backwoodsman. His Uncle Oscar gave him his introduction into tracking and he took it seriously. He would lie down to look along a fading spoor, knowing that the light patterns change from that perspective, where he might pick up the trail from a leaf or bent twig that reflected the sun differently from its neighbors. He knew that if he carefully removed the leaves from around a slight indentation there was a good chance that underneath there would be a near-perfect print in the soft earth. All these and many of the tricks of the woodsman were learned from books and relatives and all helped him in his frequent games of make-believe.

Patriotism arrived early to become a part of Junior’s makeup. In the main this was due to the stories told by his kinfolk and the school system, which at that time still required the daily Pledge of Allegiance. One of Junior’s early decisions during his schooldays was to rid himself of the name “Bernard,” which he hated. Instead he assumed the mantle of “Richard” (after a favorite cousin) and used the name from then on.

The young Richard was receiving other lessons in life, though at the time he did not recognize them for what they were. Sometimes he would accompany Grandpa Booth to town to sell eggs—a veritable fortune was to be made at ten cents a dozen. Grandpa Booth also had a little sideline that he kept to himself. He sold perfume. He would carry with him a small case containing tiny sample bottles, take orders, deliver the next week, and hope to collect the money at the same time. Most of the women who placed orders were trying in a pathetic way to escape the harsh realities and drudgery of life and for a few brief moments imagine themselves in a place far removed from the coal camps. The luxury of a perfume (even an inexpensive one) was hard for them to ignore, though few of them could really afford the purchase. After selling his eggs, Richard would meet up with his grandfather along the road and go with him to the various shacks and houses.

Sometimes there would be a little shuffling and blushing as the lady of the house said that she had no money, and Grandpa would say that in that case he couldn’t leave the perfume. Sometimes he would be invited inside to discuss the matter and he would turn to me and tell me to wait down the road a piece. He’d then appear a little later looking sort of red-faced and a bit breathless. He wouldn’t say anything and he’d avoid meeting my eyes directly and we’d go off down the road again. This could happen two or three times, and it was a long while before I realized just how those ladies were paying for their perfume and why he was getting so darned tired!

The see-saw of life took young Richard to stay once more with his father, who was now back in the Johnson’s Creek area and mixing his work between carpentry (at which he was untrained but expert) and laboring on another rented farm. His violence was as unpredictable as ever, though Richard knew the warning signs and avoided him as much as possible if he was drinking or quoting loudly from the Bible. School activity was to bring the next clash. Richard had become very good at basketball and had made the school first team. As is the way with youth, he now saw in himself the ability to become a basketball star, and the school coach, Mr. McNish, gave him every encouragement. Not so Bernie Meadows. To him, if school was to deprive him of his son’s availability as a source of cheap labor, then it was a place for learning to read and calculate—not for wasting time with ball games. Bernie steadfastly refused to let his boy stay late at school to take part in ball practice. The coach, recognizing a real talent, fixed things so that training took place during the noontime break. All went well until an important match was scheduled to take place one evening. This match was for championship points and the team was pitted against their old rival, Beckley High School. Richard decided to ignore parental protest an...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword

- Preface

- Prologue: Changing the Course of the Vietnam War

- 1. The Early Years, 1932–1947

- 2. The Young Soldier and Korea, 1947–1952

- 3. Special Forces, 1952–1960

- 4. A Lighthearted Interlude with the Brits, 1960–1961

- 5. Laos and the Learning Curve, 1962

- 6. Panama and the Fun Years, 1962–1965

- 7. Vietnam and RT Ohio, 1965

- 8. Vietnam Through an Officer’s Eyes, 1966–1970

- 9. They’ll Know We Cared: Son Tay, 1970

- 10. The Rangers, Mr. Meadows, and Delta Force, 1970–1980

- 11. “Agent” Meadows in Tehran, 1980

- 12. Footloose, 1980–1984

- 13. Entrepreneur in Peru, 1984–1989

- 14. The Golden Days in Peru, 1989–1991

- 15. The Bubble Bursts in Peru, 1991–1995

- 16. A Special Forces Marriage

- 17. The Last Patrol

- Epilogue

- Acknowledgments

- Appendix: Research Notes on the Use and Effects of Agent Orange

- Notes

- Suggested Readings

- Index