- 336 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

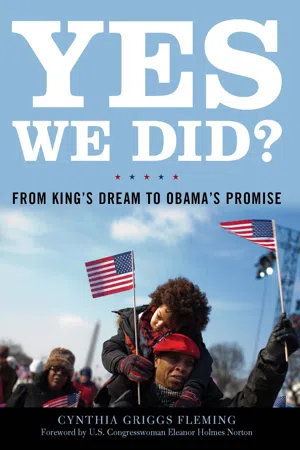

Yes, you can access Yes We Did? by Cynthia Griggs Fleming in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & 21st Century History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

The University Press of KentuckyYear

2009Print ISBN

9780813141060, 9780813125602eBook ISBN

97808131393191. Yes We Can

In late summer 2004, Barack Obama was a young black Illinois politician and the Democratic standard-bearer for a seat in the U.S. Senate. After a sordid scandal forced his Republican opponent to drop out of the race, Obama’s victory in November seemed all but certain, and he was poised to make history by becoming only the third African American since Reconstruction to be elected to the Senate. As the Democrats prepared to hold their convention in Boston that summer, the young black soon-to-be senator came to the attention of the Democratic National Committee, and they decided to ask him to deliver the keynote address to the convention on Tuesday evening. America was about to be introduced to the charismatic politician from Illinois.

From the moment Obama arrived in Boston for the convention in August 2004, there was a buzz of excitement surrounding the candidate, and he was subjected to intense media scrutiny. By the time he stepped onto the CBS set of Face the Nation in advance of his convention address, the buzz had reached fever pitch, prompting Face the Nation host Bob Schieffer to exclaim, “You’re the rock star now.”1 However, Obama already fully appreciated what a unique opportunity the DNC’s invitation presented. But if he was nervous about it, he did not show it. As he prepared his speech, the words came easily. “This was not laborious,” he said, “writing this speech. . . . It came out fairly easily. I had been thinking about these things for two years at that point. I had the opportunity to reflect on what had moved me the most during the course of the campaign and to distill those things. . . . It was more a distillation process than it was a composition process.”2

Finally, the big night came, and Obama stepped out onto the national stage. He began his keynote address with a self-deprecating characterization, calling himself “a skinny kid with a funny name” in whom this country had inspired hope.3 He quickly moved on, his voice gathering strength, and when he reached his stride, his tone and cadence made one think of a southern black preacher. He reached the crescendo as he exclaimed, “There’s not a liberal America and a conservative America—there’s a United States of America.” In response, a deep roar of approval began to build among members of the audience. “There’s not a black America and a white America and Latino America and Asian America.” After the briefest of pauses for dramatic effect, he hammered his message home: “There’s the United States of America. . . . We are one people.”4 The audience in the convention hall went wild. Delegates were cheering and weeping at the same time. Americans sitting in their homes watching this previously unknown young black man from Illinois on television were also deeply moved. It seemed that he had a magical charisma that catapulted him right into their living rooms. The stage was set for Barack Obama to make history.

After his grand debut on the national stage that summer, Obama went on to win his senate seat in the fall by the largest margin in Illinois history: he received a whopping 70 percent of the vote. His attention turned from the national scene back to his constituents in Illinois; but there were influential people on the national scene who did not forget about Barack Obama. The convention speech had left such a lasting impression that journalists continued to write excitedly about the previously unknown black politician from Illinois. And in the afterglow of his electrifying speech, other Americans from all over the country also continued to be intrigued by the young black senator-elect from Illinois. Some of those who paid close attention to Obama after he took his senate seat and began to learn his way around Washington were members of the Democratic Party establishment. When his party recaptured control of Congress in the midterm elections of 2006, the buzz surrounding the freshman senator from Illinois became more intense. Among those buzzing the loudest were the senator’s closest friends and advisers; they began to think the unthinkable and quietly began discussing the prospect of a run for the presidency. Undoubtedly, Obama’s advisers understood what a long shot it was: not only was Barack Obama a black man in a country that had never elected a black president, but he was a freshman senator who had barely begun to learn his way around the corridors of power in the nation’s capital.

Regardless of how improbable it was, however, months before the others around the young senator began to speak of the possibility of an Obama presidential candidacy, Barack and Michelle Obama’s oldest daughter, Malia, had no trouble envisioning it. The subject came up on the day Obama took his oath of office for the Senate. Right after the solemn ceremony, he and his family were strolling around the capitol grounds savoring the moment. At one point on that magical afternoon, Malia paused and earnestly looked up at her father, asking, “Daddy, are you going to be president?”5 Anyone who overheard the innocent question six-year-old Malia asked her father that afternoon would have simply smiled politely at the child’s obvious faith in her father. But from her vantage point as a twenty-first-century black child who had never had her vision of prospects and possibilities circumscribed by the ugly reality of legal segregation or the frightening brutality of racial violence, the question was a perfectly logical one.

Some months later, Barack Obama was part of a crowded field of Democratic hopefuls in the race for the party’s nomination. Then in January 2008, when he went to the snowy white state of Iowa, Obama emerged from the pack to make history again. January 3, 2008, was a cold, snowy night in Des Moines, Iowa. But inside the hall where presidential candidate Barack Obama, the forty-six-year-old junior senator from Illinois, was delivering his victory speech after winning the Iowa Caucus, the air was warm and the atmosphere crackled with excitement. The hall was jam-packed, and the nearly all-white crowd roared its approval when Obama said, “Hope—hope is what led me here today—with a father from Kenya; a mother from Kansas; and a story that could only happen in the United States of America. Hope is the bedrock of this nation; the belief that our destiny will not be written for us, but by us; by all those men and women who are not content to settle for the world as it is; who have the courage to remake the world as it should be.” Obama’s victory as a black candidate in one of the whitest states in the country was remarkable. Some even said it was a miracle.

Col. Alexander Jefferson is also black. That January evening, Colonel Jefferson was sitting in his living room in Detroit, Michigan, the blackest city in America, and he was thrilled by Obama’s victory. Jefferson is a retired army officer, and even in his eighties his military bearing is still obvious: his body is slender and straight, and his gaze is just as sharp as it was over fifty years ago when he was flying a plane as one of the famed Tuskegee Airmen searching the skies for German aircraft. A native Detroiter, he is acutely aware that his city has an astronomical budget deficit, an unemployment rate that is out of control, and a public school system in crisis. But despite the problems all around him, Jefferson was heartened by Obama’s victory. When he reflects on Obama’s Iowa victory and his ultimate success in the national election, he shakes his head in amazement. “I never thought I’d see it happen in my lifetime,” the old man says in a voice tinged with wonder.6 Regardless of whether Obama’s success will have any impact on his city’s crisis, Colonel Jefferson, like African Americans everywhere, basks in the symbolism of this black electoral victory. However, it is not only Obama’s color that strikes a chord with African Americans, but also his words. That night in Iowa when the he clearly associated his quest for the presidency with the black freedom struggle of the 1960s, African Americans smiled. Obama said, “Hope is what led a band of colonists to rise up against an empire; what led the greatest of generations to free a continent and heal a nation; what led young women and young men to sit at lunch counters and brave fire hoses and march through Selma and Montgomery for freedom’s cause.” Obama was making a clear connection between the civil rights movement of the 1960s and his historic candidacy, and black people, especially those from the civil rights generation, said “Amen.”

Barack Obama’s unprecedented electoral success came exactly forty years after Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., the most potent black leadership symbol of the twentieth century, was assassinated. Thus, even as African Americans look forward to the tantalizing possibilities for African American progress that an Obama presidency holds, many find themselves looking backward, reflecting on the impact on black progress of King’s death forty years ago. Just as Barack Obama has become the most famous black leader in the twenty-first century, Martin Luther King had become the most famous black leader of the twentieth century by the time of his death. King never ran for political office, never held any government post at all. Nevertheless, he was widely admired because of his unshakable commitment to the cause of social justice, his ability to empathize with the disparate elements of his broad constituency, and his remarkable oratorical skills.

It was his empathy with one group of his constituents, striking sanitation workers in Memphis, Tennessee, that prompted one of the most masterful speeches of his career: it was the last speech he ever gave. King delivered that speech on the evening of April 3, 1968, in Memphis. It was a stormy night, and as he spoke, brilliant flashes of lightning and loud claps of thunder eerily punctuated his powerful words: “I’ve been to the mountaintop. . . . I’ve looked over and I’ve seen the Promised Land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight that we as a people will get to the Promised Land.”7 The audience was swept up in the confidence of King’s prediction, and their applause was deafening. After it was over, King was so drained that two of his close associates, Rev. Ralph Abernathy and Rev. Samuel Billy Kyles, had to help him to his seat. Even those closest to King, who had heard him speak countless times before, realized that they had just witnessed a remarkable performance, even for King.8

The next day, King spent hours with close advisers planning the Poor People’s Campaign. They met in room 306 of the Lorraine Motel in the heart of Memphis’s black community. By that evening, the mood of the group turned lighthearted, and as they engaged in good-natured banter, a pillow fight broke out. It was a remarkable sight: Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and some of the best-known leaders in the Southern Christian Leadership Conference pummeling one another with pillows as they laughed, teased, and joked. Local Baptist minister and activist Samuel Billy Kyles turned into the parking lot of the Lorraine Motel at five o’clock that afternoon. After parking his car, he walked up the stairs closest to room 306; he had come to pick the group up and take them to his house for dinner. Although Kyles had told King he would be there by five, he was not surprised that King was not ready. As he recalls, “Doc was always late, so I told him I’d be there by 5:00, and I knew that he would probably be ready by 6:00.” Kyles’s strategy worked: as six o’clock approached, the pillow fight broke up, and the others drifted off to their rooms to freshen up for dinner. Only King, Abernathy, and Kyles were left in room 306. All the motel rooms opened out onto a balcony overlooking the parking lot and a swimming pool below, and just then King and Kyles walked out of room 306 together onto the balcony. They paused, and then Kyles turned and began walking toward the stairway to his right. King was left standing alone on the balcony, gazing off into the distance. Abernathy was still in room 306, putting the finishing touches on his appearance. By this time, other members of SCLC’s inner circle had already descended the stairs to the parking lot.9

Kyles was halfway between the stairs and the lone figure of King lost in thought on the balcony when he heard the loud report of a gunshot. He froze. It took his mind a few seconds to process what had just happened behind him. When he whirled around, he saw King lying on his back with a gaping wound to his jaw. In the parking lot below, James Bevel, a young Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) strategist, was actually looking up at the balcony at the precise moment when the shot rang out. In that awful instant, Bevel was smiling, still buoyed by the playful mood left over from the pillow fight. And besides, Bevel recalls, “I thought Bernard [Lafayette] was playing a firecracker trick on us.” Bevel explains, “Bernard used to do this kind of stuff. He’d light a firecracker and then fall out.” But as the sight of King’s fallen body finally registered on Bevel’s consciousness, the young activist’s smile disappeared, replaced by a look of shock, horror, and profound disbelief. With tears in his eyes, the young activist mumbled to nobody in particular, “No. That’s King. He don’t play like that.”10

Kyles closed the distance between himself and the fallen King in three giant steps just as Bevel and the others in the parking lot below came charging up the stairs. With barely a pause, Kyles quickly ran into room 306 to call for an ambulance. In those days, many motel phones did not have dials; the only way to make a call was to pick up the receiver and wait for the hotel operator to answer. Kyles lunged at the phone and grabbed the receiver almost before his whole body was in the room, but the operator did not come on the line. The frantic minister waited for some seconds and then rushed back out on the balcony and asked one of the many Memphis police officers hovering around the scene to use his radio to call for an ambulance. It was only later, after the chaos had subsided, that Kyles discovered that the motel operator, who happened to be the motel owner’s wife, had left the switchboard and run out into the parking lot when she heard the shot, leaving the untended switchboard buzzing. When she looked up at the balcony and realized the enormity of the tragedy unfolding there, she collapsed from a massive heart attack right on the spot. She later died without ever regaining consciousness.11

In a matter of minutes the ambulance arrived, and Memphis police officers helped the attendants carry the wounded King down the stairs and into the ambulance. As it took off, tires screeching and siren wailing, many of those left behind who had just been laughing and talking and throwing pillows at King and at each other looked on in silence, tears coursing down their cheeks. For all of these men, the loss they suffered that day as a result of the events on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel was a very personal one. They had prayed with Martin Luther King, they had marched with him, they had plotted strategy with him, they had celebrated with him, and they had cried with him. Now they were crying for him and for themselves. How could they continue the struggle without him?

All over the country, African Americans recoiled in shock and horror and reacted with rage when they heard the awful news. Even those who had disagreed with parts of King’s philosophy were deeply affected. That moment on April 4, 1968, was a defining moment for the African American freedom struggle and for the future direction of African American leadership. During his brief thirteen-year career as an activist, King had achieved a visibility and renown unparalleled by any other African American leader in the history of America. By this time, King’s name had become synonymous with the civil rights movement in the minds of most Americans, black and white, and he seemed equally comfortable meeting with President Lyndon Baines Johnson in the White House or with black sharecroppers in the Black Belt in Alabama. King’s message of nonviolence and Christian love gained the attention of many Americans during the turbulent decade of the 1960s. The learned phrases that were so characteristic of King’s speeches were a consequence of his eastern education, and they mixed easily with his soft southern accent and the simple homilies from his African American culture. These elements, combined, enabled him to craft eloquent orations that appealed to his varied countrymen.

But the Martin Luther King this country has mourned and eulogized ever since that fateful day in Memphis is not the man who died April 4, 1968. Instead, in the days and weeks following the traumatic assassination, many Americans reached back into the past and resurrected a younger version of King to mourn. Substituting their idealized version of King absolved them of the responsibility to face the stubborn and continuing problems that the mature King recognized before his death. The younger, more popular version of Martin Luther King Jr. is still alive and well in the new millennium, and he seems to be caught in some sort of cosmic loop, forever standing on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C., delivering his “I Have A Dream” speech over and over again. Many Americans who were alive at the time nostalgically remember the sight of the young preacher standing in the hot sun while the musical phrases of the masterful speech rolled off his tongue: “Now is the time to rise from the dark and desolate valley of segregation to the sunlit path of racial justice. . . . Now is the time to make justice a reality for all of God’s children.” King admonished his audience, “In the process of gaining our rightful place, we must not be guilty of wrongful deeds. Let us not seek to satisfy our thirst for freedom by drinking from the cup of bitterness and hatred. . . . Again and again we must rise to the majestic heights of meeting physical force with soul force.” King’s voice soared in mighty triumph as he ended his speech: “Free at last! Free at last! Thank God Almighty, we are free at last!” It was a message that made Americans feel good about themselves and optimistic about the future of their country.12

By the time Martin Luther King Jr., the mature activist, came to Memphis in the last hours of his life, he had changed. Standing on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel on April 4, 1968, and gazing off into the distance, he was able to see far beyond the colored and white signs, the separate drinking fountains, the separate bathrooms, and his “I Have a Dream” speech. This more mature King had advanced to a point in his thinking where he focused on basic issues of economic justice that reached far outside the South. He had come to believe that African Americans suffered b...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Participants

- Foreword

- Acknowledgments

- Prologue

- 1. Yes We Can

- 2. Black Leadership in Historical Perspective

- 3. After King, Where Do We Go from Here?

- 4. The Media and the Message

- 5. From Protest to Inclusion

- 6. The Continuing Challenge of Black Economic Underdevelopment

- 7. Black Culture Then and Now

- 8. Black Community and Black Identity

- 9. A Crisis of Victory

- Epilogue

- Notes

- Bibliographic Essay

- Index