![]()

The Witness to Impartial Love

John G. Fee and the Founding of Berea College

[Berea] was founded by zealous missionaries before the war, to meet the wants of the region. Notwithstanding its earnest advocacy of liberty, and opposition to caste, it grew rapidly in reputation and efficiency. It became so great apower, that leading men in this section of the State said that it was endangering slavery and must be suppressed. Accordingly the Teachers and leading Trustees were driven from the State. In due time they returned.

First Catalogue of Berea College

AMERICA in 1855 was a nation awash in excitement. Reformers denounced the evils of liquor and secret societies. Women’s rights advocates such as Lucy Stone, Abbie Kelly Foster, and Antoinette Brown Blackwell gained a national hearing. For many reformers, however, slavery was the dominant issue. Amid border skirmishes between proslavery and “Free Soil” militias, the abolitionist John Brown joined his sons and became the leader of an abolitionist group in “Bleeding Kansas.” Addressing an antislavery society gathering in New York City, Ralph Waldo Emerson estimated that $200 million was needed to purchase the freedom of every slave in the South. Frederick Douglass published My Bondage, My Freedom. In that year John G. Fee, his wife, Matilda, and others opened a school in Kentucky that attracted local attention for good teaching, lively preaching, and abolitionism. The values embodied in the school’s constitution bore witness to the tremendous commitment and sacrifice of Berea’s founding generation.

Charles Grandison Finney. His revivals not only converted individual souls but also motivated social reform.

Roots

The founding of Berea College was characterized by several influences manifested in various reform efforts in nineteenth-century America. The first of these influences was personified in Charles Grandison Finney (1792-1875). Beginning his career as a lawyer, Finney experienced an intense conversion while studying the Mosaic law. He embraced the New School Theology wing of Presbyterianism, which was less strict in interpreting Calvinist doctrines such as election and predestination. His preaching emphasized the mutual cooperation between the work of the Holy Spirit and the human spirit in conversion. His revival meetings were electrifying, featuring converts falling to their knees in tearful surrender, public prayers by women, and an anxious bench in front of the assembly for those under conviction of sin. These meetings connected conversion and revival to a sense of social reform and concern for others. Finney’s linkage between the commonality of sin and the universality of grace demonstrated itself in a type of Christian egalitarianism.1 John G. Fee was converted to abolitionism while attending Lane Seminary in 1842. Two classmates, John Milton Campbell and James C. White, were instrumental in Fee’s reconsideration of slavery. They impressed two Scriptures with particular impact on Fee: “You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, . . . and your neighbor as yourself” and “Do unto others what you would have them do unto you.” Fee was convinced that these principles were critical to his obedience to God. “Lord, if needs be,” Fee prayed, “make me an abolitionist.” Fee’s conversion was total. “The surrender was complete,” Fee recalled. “I arose from my knees with the consciousness that I had died to the world and accepted Christ in all the fullness of his character as I then understood Him.”2

Lane Seminary, founded near Cincinnati in 1829, formed a second influence in the founding of Berea. Students performed manual labor in addition to their studies. New and Old School Presbyterians fought for control of the seminary, but New School views rose under the influence of the radical New York philanthropist Arthur Tappan and Lyman Beecher, the seminary’s president. Lane was one of the first schools in America to admit African Americans. Under Beecher’s leadership the school espoused a moderate view of the slavery question, encouraging gradual abolition and colonization, a movement that argued for the voluntary resettlement of African Americans in Africa.3

Lane’s moderate position on slavery was directly challenged by one of Finney’s more radical disciples, Theodore Weld. Already an advocate for temperance, manual labor, and education for women, Weld entered Lane as a recent convert to the abolitionist cause. In the spring of 1834 Weld organized an eighteen-day debate that changed the students’ stance from gradual to immediate abolition. Students promoted pro-abolition views and began ministries among African Americans in Cincinnati. Fearing mob violence because of their proximity to proslavery sympathizers, the seminary trustees voted to restrain the students from any activity not approved by the faculty. The students rebelled and by 1835, 95 of the 103 students had left the school. Along with Professor John Morgan, who had also been expelled, some 75 of these students proclaimed themselves “Lane rebels.”4

The rebels found refuge at Oberlin, which had been founded in 1831 by John Jay Shipherd. The school’s ideals followed the ministerial example of the missionary John Frederick Oberlin (1740–1826). Working among the poor of the Vosges Mountains in France, Reverend Oberlin preached a gospel that featured a combination of fervent German Lutheran pietism and the social and educational theories of the French Enlightenment. John Oberlin was the first to train and employ women as teachers, and his campaign of social uplift led many mountain people out of ignorance and poverty. For his own part, Shipherd imagined clearing the Ohio wilderness for a communal settlement and manual labor institute. A women’s department and seminary would be added as the school developed.5

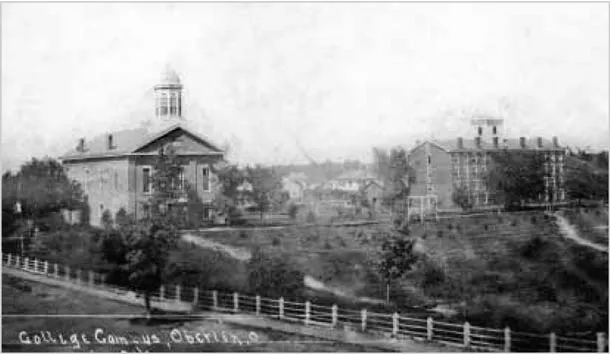

Oberlin College campus, 1860. Many of Berea’s founders and early teachers were associated with Oberlin. All but three of Berea’s presidents have been students or teachers at Oberlin.

The arrival of the Lane rebels transformed the emerging Oberlin school and colony. Shipherd visited the displaced Lane seminarians and, aided by donations from Arthur and Lewis Tappan, invited the exiles to Oberlin. Asa Mahan, a Cincinnati pastor who had supported the rebels, was named the school’s first president. Finney was called as professor of theology, and Professor Morgan also joined the faculty. At Oberlin free speech was unconditionally guaranteed on all reform issues, and African American students were soon admitted. Oberlin was also the first coeducational college in the United States. The manual labor program helped students and the institute meet educational costs. In 1858 the school was formally designated as Oberlin College. Central to all Oberlin’s early innovations was Finney’s perfectionist theology of the conversion of sinners and Christian sanctification.6

The American Missionary Association also profoundly influenced Berea’s beginnings. Formed in 1846 from four separate missionary societies, the AMA concentrated on home missions, work among Native Americans, missionary activities among blacks in the West Indies, and African missions. The Tappans were the principal philanthropists behind the AMA, and the association’s first president was Joseph H. Payne, a Lane rebel and Oberlinite. George Whipple, principal and professor at Oberlin, was perhaps the association’s most influential member, serving as both corresponding secretary and editor of its publication, the American Missionary. The AMA was distinctly abolitionist in character. Missionaries committed to their antislavery work were exhorted to “talk it, preach it, pray it, vote it.”7

Otis Waters. Along with George Candee and William E. Lincoln, Waters was an Oberlin graduate. He taught schools in Berea and in neighboring Rockcastle County. His innovative methods let him use the short school terms to full advantage.

Until 1860 more than nine-tenths of all missionaries sent out by the association were Oberlin graduates. Three of Berea’s earliest teachers (Otis Waters, George Candee, and William E. Lincoln) were Oberlin graduates and funded by the AMA. Berea College’s founders, John G. Fee and J. A. R. Rogers, were supported in their rural pastorates by the AMA. The AMA would also hold funds in trust for the college as it reemerged after the Civil War.8

Berea’s founders and ideals were rooted in the work of Finney, Lane Seminary, Oberlin College, and the American Missionary Association. Fee and Rogers embraced Oberlin’s values of interracial coeducation, free speech, manual labor, and Christian perfectionism. All these grand ideas had found success in the relative safety of the North. Fee’s great adventure now was to put these values into practice in the midst of slavery in his home state of Kentucky.

A Southern Abolitionist

Located in the middle of a sparsely inhabited wilderness, the fledgling school opened in 1855 in a one-room clapboard building, the old district schoolhouse. Berea enjoyed a good reputation, even among local slaveholders. This view continued despite the antislavery views held by Waters, Lincoln, and other northern men who taught in the school. Many people in Madison County were less sure of the school’s founder, John G. Fee, however. Born September 9, 1816, in Bracken County, Kentucky, Fee attended Lane Seminary to prepare for the ministry and returned home convinced of the evil of slavery. He parted with the Presbyterian Church, in which he had been ordained, because that denomination was not sufficiently opposed to slavery. Unable to convince his family of his views, Fee was eventually disowned and disinherited by his slaveholding father for his abolitionist stance.9

Lacking support from a denomination or his family, Fee nevertheless enjoyed the devotion of his wife, Matilda Hamilton Fee. Zealous in support of Fee’s cause, she was described by the abolitionist William Goodell as being as thoroughly abolitionist as her husband.10 In 1844 Fee founded an antislavery church in the mountains of Lewis County and received financial support from the American Missionary Association. In addition, he pastored a number of “free” churches in rural Ohio River counties. He attended and participated in antislavery meetings in northern cities, where he was a popular speaker. Fee gained some reputation in the North as the author of abolitionist pamphlets and of a notable book, An Anti-Slavery Manual, published in 1848.

Fee also found a key source of support in the South. Cassius Clay, a prominent Madison County landholder, politician, and antislavery advocate, found in Fee an ally for free speech and a potential means of expanding his own influence in the mountains of eastern Kentucky, “where there were but few slaves and the people courageous.” Clay had been converted to the antislavery cause in 1832 when, as a student at Yale University, he was deeply impressed by a sermon given by William Lloyd Garrison. Returning to Kentucky, Clay established an antislavery newspaper, the True American, in 1845. Several of Fee’s antislavery articles were published in the pages of Clay’s newspaper. Clay had freed his own slaves by 1844, and his open opposition to the “peculiar institution” aroused bitter hostility and violence. Whereas Fee went about his circuit unarmed, Clay was physically prepared to defend his ideas, having a pistol and a bowie knife close at hand.11

Clay requested a boxful of Fee’s Manual in 1853 for distribution in Madison County and later that year invited Fee to hold a series of religious meetings in an area of botto...