eBook - ePub

Drawing the Line

The Untold Story of the Animation Unions from Bosko to Bart Simpson

- 440 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Drawing the Line by Tom Sito in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Animation. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

The World of the

Animation Studio

The Cartoon Assembly Line

Any nut that wants to spend hundreds of hours and thousands of drawings to make a few feet of film is welcome to come join the club!

—Winsor McCay

Animation is a strange art form. It is art and theater produced in industrial quantities. Many more drawings and paintings are discarded than appear in a final film. Inspiration and creative talent are treated like so much raw material. Who are the people who work in such a system? An animation crew is a collection of dozens, often hundreds, of artists, writers, technicians, and support staff closeted in some large space, usually uncomfortable, for months, trying to create a film that looks like it was made by one hand. When working on an animated feature-film deadline, artists typically put in ten- to fourteen-hour days, seven days a week. This is as true for modern digital imaging as it was for the silent black-and-white films. Animators spend more time with their coworkers than with their own families.

In 1938, Ted Le Berthon, a newspaper columnist, wrote: “Cartoon studios are hard-driven fable factories, jammed with sweating commercial artists who work at breakneck speed on monotonous routines at meager pay. . . . The whole strange business gets in their blood. They think it, dream it, and live it. It is hard on their nerves. The main industrial ailments are eyestrain, neuritis, arthritis and alcoholism.”1 I had a conversation with director Robert Zemeckis in Radio City Music Hall at the premiere of his award-winning Who Framed Roger Rabbit? (1988). At the wrap party, he marveled at the way an animation crew works: “I’m used to using the same crew, and we go from picture to picture. But you animation folks come together and live with each other for years! You marry each other, bear each other’s children, bury each other’s grandfathers, and when the film is over, phfftt! You scatter to the four winds.”

Companies, like empires, rise, dominate, and fall. The make-or-break film becomes just another box in the stacks in a video store, or another download. Yesterday’s headline-grabbing studio soon becomes just a file in a licensing attorney’s office and a footnote in a film-trivia book. But the hard core of professional animators moves on from project to project. There is an old saying among animation veterans: “You always work with the same people. Only the producers change.” The long hours of confinement and mutual ordeal create a camaraderie unique in film-making.

For example, in 1975 I first met Eric Goldberg in New York, where he was animating educational films at a small company called Teletactics. A year later we worked on the feature film Raggedy Ann & Andy (1977). Then Eric worked in London, and I worked in Toronto. In 1982, we worked together in Hollywood on Ziggy’s Gift, a TV special. Back in Los Angeles, we hooked up again at Walt Disney Studios for Aladdin (1992) and Pocahontas (1995). I went on to DreamWorks SKG, then to Warner Bros., where we got together again for Looney Tunes: Back in Action (2003). This is typical in the film business. We sometimes call ourselves animation gypsies or migrant film workers.2 Our social network is tight and global. If an animator takes off his toupee in Los Angeles, his animation buddies in London, Manila, Seoul, Barcelona, Orlando, Berlin, and Istanbul will know in short order.

What kind of person wants to work in this kind of field? Every studio has a kaleidoscope of colorful characters. There are all nationalities, all colors, all pressed into the same space. Traditionally animation artists have come from the quieter side of the classroom, from the ranks of the comic-book reading, reticent kids who like spending long hours in solitude.

So how did it get this way?

Art by assembly line is not a new idea. Artists throughout history have used apprentices and associates for large jobs. In the seventeenth century, artists like Rubens and Van Dyck had an assembly line of underpainters, finishers, and toucher-uppers, with clients having rotating sitting appointments. Apprentices mixed colors, applied varnish, even hand-carved pencils and made paper. Michelangelo is noted in contemporary accounts as being unique because he dismissed his staff and worked on the Sistine Chapel ceiling without helpers. Earlier, there were medieval guilds of cathedral builders who crossed borders to work whenever the duke of Chartres or someone got the green light for a new job. If the contract was for length of production on a new Gothic cathedral, it must have meant 150 years worth of work. Talk about job security!

When motion pictures were invented, the young medium hired technicians from circuses and vaudeville. They came around looking for work when the big-top shows were in their winter quarters. Their special skills of hanging lights, applying makeup, and painting scenery were sorely needed in the new industry. Circus job titles—gaffer, grip, best boy—were even incorporated into film jargon.

In 1913, John Randolph Bray was making animated shorts in the manner of pioneer cartoonists Winsor McCay and Emile Cohl; that is, by making thousands of drawings alone. For example, for The Sinking of the Lusitania (1917), McCay and his assistant, John Fitzsimmons, took twenty-two months to make twenty-five thousand drawings. The backgrounds were drawn on the same pages as the character drawings.3 After great exertion, Bray produced his first cartoon short, The Artist’s Dream. He sold it to Pathé Pictures, and that led to a request for a series of animated shorts to run on a regular delivery schedule in Pathé theaters. Bray realized he needed to do things differently because the workload was far beyond his individual capacity. So he turned to the newfangled notion of the specialized production line. Frederick Taylor’s landmark 1911 book, The Principles of Scientific Management, theorizes the concept.4 These theories were utilized by automaker Henry Ford to develop his famous assembly line, which soon became the standard for all American heavy industry. Bray and his production manager, wife Margaret, read Taylor’s book and decided to adapt the assembly-line process to making animated cartoons.

Instead of one master cartoonist drawing everything, the process was broken into specific jobs. One person made up the story, another designed a character, and another animated it, that is, created the motion by drawing keyframes. (Keyframes are the animator’s drawings of sequential steps of an action that, when run at film speed, look like movement.) Another artist assisted or cleaned up the drawings, others drew the remaining in-between drawings needed to complete the actions the animator designed. Still another painted the characters onto the new acetate cels developed by Earl Hurd. (Before the invention of acetate celluloids, assistants were called “blackeners” because they inked in the little black bodies of a Felix the Cat or Mickey Mouse.) Another painted background landscapes, one more photographed the drawings onto film. A similar studio was set up in the Bronx under Raoul Barré, but Bray’s ideas set the stage for animation production for the rest of the twentieth century. Many of Bray’s supervising artists (he called them foremen) went on to open their own studios and copy Bray’s production techniques. These artists included Max Fleischer, Paul Terry, and Walter Lantz. Bray used the term “cheapmen” for artists with less-influential positions.5

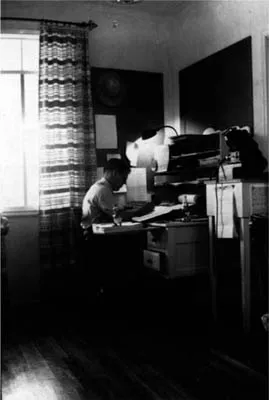

Animator Al Eugster at his desk at the Walt Disney Hyperion Studio annex, working on Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, circa 1937. Eugster was a dependable staff animator who worked at many of the top studios in the golden age of animation. Besides Disney’s he worked at Fleischer’s, Famous, and Sullivan’s and finished his career doing commercials. Every morning he lined up on his desk all the pencils he intended to use, and all the cigars he intended to smoke. Courtesy of the Al Eugster Estate and Mark Mayerson.

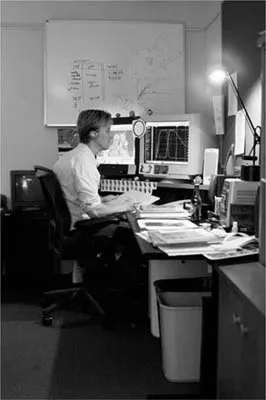

Animator Kevin Koch at his digital workstation on Over the Hedge, at DreamWorks Animation, circa 2005. Even though the equipment has changed radically, the animator faces the same creative challenges his pencil-sharpening ancestor possessed. No cigars, though. Koch became Animation Guild president in 2001. His credits include Shrek 2 and Madagascar. Courtesy of DreamWorks Animation.

Gregory LaCava was probably the first animation director.6 That was in 1916 at the Hearst studio. By the early 1920s, the jobs of animation checker and storyboard artist had been created. (A checker was roughly equivalent to a proofreader, performing quality control and numbering the artwork.) A separate artist, called a layout artist, was needed to define the staging of the storyboard sketch before animating. Film editors and, later, sound editors were added. In the late 1930s, to satisfy his desire for realistic animation, Walt Disney created a separate department for special-effects animators—artists who specialized in drawing smoke, flame, water, and lightning. In the 1950s, Jay Ward, Bill Hanna, and Joe Barbera modified the theatrical-shorts production line for the special needs of large-scale television production (see chapter 7).

Bray’s industrialized production line became the norm for all animated films from Colonel Heeza Liar in 1914 to today’s $500 million digital mega hits. This system determined that the American animation studio would be an industrialized plant and not a cooperative atelier of artisans. The unions that were eventually created to support animation workers were also conceived on an industrial model created by American Federation of Labor (AF of L) founder Samuel Gompers. As a young cigar maker in 1877 Gompers witnessed the national railroad workers strikes then called the Great Upheaval. These strikes flared into ugly street battles with guns and bombs. Strikers set fire to railroad sheds, and militia fired their rifles indiscriminately into crowds of workers’ families. Anarchists set off bombs in train boilers and shouted “Hurrah for anarchy” as they were hanged. The news of the American labor unrest reached Europe, where Karl Marx wondered if the worker revolution he envisioned might first start in America. Shocked by the useless carnage, Samuel Gompers conceived a new union of craftsmen governed not by a political committee but by a board of officers who could talk as equals to corporate leaders. His AF of L had an executive board elected by the membership with a president, vice president, and sergeant at arms. This became the model for all American labor unions. At first the AF of L was to be a union only of skilled craftsmen, like animators. In 1951 it joined with the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO), the alliance of unskilled laborers.

In the field of animation, new studio head John Randolph Bray had created a paradox. His assembly line for art created a class of workers who (still today) see themselves as individual artists yet also as part of a company that needs their output to blend into the whole. But Bray ensured that they could count on work and paychecks every week. The assembly-line system relieves artists of the burden of mastering business affairs, in addition to the skills they need in drawing, acting, natural science, action analysis, and cinema. They just go to work and let the big boss worry about making deals and signing contracts. Bray also defined the relationship of the animation studio head to his staff. He wore suits and high, starched collars and glared at his staff through his pince-nez. He set his desk on a level above his open production floor so he could bark orders down at the artists. James “Shamus” Culhane recalled Bray as cool and aloof. He said as a young boy he was afraid to even wish “Mr. Bray” a good morning.7

In the Depression years of the 1930s, animation was still a young industry filled with young, single people making good money while their relatives stood in breadlines. The young artists lived and worked as a team under pressure-cooker conditions for countless hours, so when the time came to loosen up and celebrate, they partied hard. In 1938 when Walt Disney threw a huge Christmas party in his studio for his staff after Snow White’s successful premiere, the animation crew went on a wild debauch. People got so drunk they fell out of windows. Luckily, the party was on the ground floor, so no one was hurt. But the studio was so trashed afterward that Walt decided to hold all future parties in rented space. A year later he threw a company party at a dude ranch north of Norco, California. When Walt and Roy Disney and their wives drove up to the lodge a day later, they found something more like a Roman orgy than a Christmas party. Guys and gals were running naked from room to room, and one animator drunkenly galloped a horse up a stairway and down a second-floor hallway. Maurice Noble recalls standing at the head of the stairs waving a welcome to his bosses. Walt and Roy got back in their car and left before local reporters could associate them with the wild goings-on.8

From 1928 to 1955, American animation exploded with the creation of a legion of characters and films as famous now as they were sixty years ago. The Max Fleischer studio had Betty Boop, Koko, and Popeye; Leon Schlesinger’s studio (later Warner Bros.) had Bugs Bunny, Daffy Duck, Porky Pig, Elmer Fudd, the Road Runner, and Wile E. Coyote. Walt Disney had Mickey Mouse, Donald Duck, Goofy, and the Big Five feature-length films: Snow White, Fantasia, Bambi, Pinocchio, and Dumbo; MGM had Tom and Jerry, Droopy Dog, and the Tex Avery cartoons. Walter Lantz had Woody Woodpecker, Andy Panda, and Chilly Willy; Terrytoons had Gandy Goose, Barney Bear, Mighty Mouse, and Heckle and Jeckle. After 1945, United Productions of America (UPA) expanded the range of animation into new styles and modern interpretations with Mr. Magoo, Gerald McBoing-Boing, and the Telltale Heart. The skills of drawn performance and graphic storytelling reached a level of artistry envied today. It was truly a golden age.

We like to think of those times as the golden age not only of animation art but of working conditions. When modern animators think of animation workers of the 1930s and 1940s, they may rhapsodize that artists then lived on the love of cartoons and had no pressures. Today we labor ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction Why a History of Animation Unions?

- 1. The World of the Animation Studio The Cartoon Assembly Line

- 2. Suits Producers as Artists See Them

- 3. Hollywood Labor, 1933–1941 The Birth of Cartoonists Unions

- 4. The Fleischer Strike A Union Busted, a Studio Destroyed

- 5. The Great Disney Studio Strike The Civil War of Animation

- 6. The War of Hollywood and the Blacklist 1945–1953

- 7. A Bag of Oranges The Terrytoons Strike and the Great White Father

- 8. Lost Generations 1952–1988

- 9. Animation and the Global Market The Runaway Wars, 1979–1982

- 10. Fox and Hounds The Torch Seen Passing

- 11. Camelot 1988–2001

- 12. Animation . . . Isn’t That All Done on Computers Now? The Digital Revolution

- Conclusion Where to Now?

- Appendix 1. Animation Union Leaders

- Appendix 2. Dramatis Personae

- Appendix 3. Glossary

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index