![]()

RELIGIOUS ASPECTS OF SOUTHERN CULTURE

![]()

“JUST A LITTLE TALK WITH JESUS”

Elvis Presley, Religious Music, and Southern Spirituality

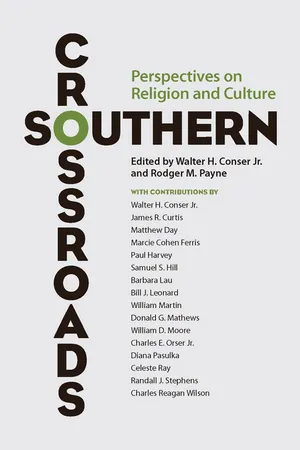

CHARLES REAGAN WILSON

Popular religious music, such as that sung by gospel quartets and country music bands, is a powerful expression of southern religious life. Nurtured in Nashville and Memphis, in local congregations and regional songfests, this music sometimes transgressed boundaries, though often it confirmed them. Using the person of Elvis Presley as a window to explore southern religious practice and belief, Charles Reagan Wilson identifies a distinctive southern spirituality that is often overlooked in studies of the South. Wilson finds that Elvis’s journey from the Spirit-filled Pentecostal faith of his youth to the experimental spirituality of the 1960s mirrors changes in American as well as southern culture. Moreover, Wilson investigates the ethos of Protestant evangelicalism, with its dynamic of individualism and personal piety, a theme that is also examined by others in this volume.

In December 1956 Elvis Presley dropped in at Sun Studios in Memphis, just as a Carl Perkins recording session was ending. Presley was now a national star, having transcended earlier that year his previous status as a regional rockabilly performer. That special day became known as the Million Dollar Session because of the supposed “million dollars” worth of talent that included Presley, Perkins, Jerry Lee Lewis, and, briefly, Johnny Cash. An open microphone recorded a lively jam session. For the student of southern religious music, it was an especially revealing moment. In addition to improvising with country, blues, and early rock songs, the group sang from the common body of southern religious songs, some of them gospel tunes that dated from nineteenth-century revivals, others African American spirituals, others popular gospel-quartet numbers. All of these young performers who had grown up in the countryside near Memphis knew the songs, and when one started singing, the others easily fell into supporting lines. They had all come out of church backgrounds and would have been familiar with “Farther Along,” “When God Dips His Love in My Heart,” “Blessed Jesus (Hold My Hand),” and “As We Travel Along on the Jericho Road.” Elvis sang “Peace in the Valley,” an old classic written by black composer Thomas A. Dorsey and the song he sang on the “Ed Sullivan Show” to defuse public concerns that he was an immoral renegade destroying America’s youth. Between songs the boys talked about the white gospel quartets that were so active around Memphis, an epicenter of white and black gospel traditions.1

“Just a Little Talk with Jesus” was an especially revealing song of southern spirituality that day in Sun Studios, two years after the 1954 Brown decision and one year before the Soviet satellite Sputnik, during a decade that launched extraordinary cultural changes in the South. Elvis knew the song profoundly, singing a lively version and then slowing down the pace to fit the mood of the lyrics. The song’s narrator tells the essential evangelical story of one “lost in sin” but not without hope because “Jesus took me in.” When that happened, “a little light from heaven” filled his soul. Redemption is seen in the next lines, which say God “made my heart in love and He wrote my name above.” Despite “doubts and fears” and even though “your eyes be filled with tears,” “my Jesus is a friend who watches day and night.” In the end, “just a little talk with Jesus gonna make it right.”2

The Million Dollar Session is an appropriate introduction to the importance of Elvis Presley in understanding the role that music played in defining a distinctive southern spirituality and the impact on that relationship of the dramatic changes in the South over the roughly two decades between that day in Sun Studios in 1956 and Presley’s death in Memphis in 1977. Charles Wolfe, Peter Guralnick, and other historians and journalists have written about Presley’s relationship to the gospel music tradition, but the broader question of how Presley can help open up the unexplored issue of southern spirituality has not been explored.

Studies of “American spirituality” that stress the distinction between “religion” and “spirituality” have recently appeared. Robert Wuthnow, a leading student of American spirituality, concludes that this new scholarly work reflects increasing popular interest in spirituality. People see spirituality as “somehow more authentic, more personally compelling, an expression of their search for the sacred,” whereas religion suggests a “social arrangement that seems arbitrary, limiting or at best convenient.”3 Despite the new popular and scholarly interest in American spirituality, none of the scholarly works even mentions the South or southerners, and certainly none addresses a regional expression of spirituality that comes out of the white working-class culture of the South. Neither the Encyclopedia of Religion in the South nor the Encyclopedia of Southern Culture include entries on “spirituality,” and a survey of classic works by historians Samuel Hill, David Edwin Harrell, Wayne Flynt, and others suggest they have seldom dealt directly with “spirituality” in the context of a southern regional religious tradition.

Historian Samuel Weber’s recent article, “Spirituality in the South,” prepared for The New Encyclopedia of Southern Culture, has intentionally opened up the topic for analysis, but the essay stresses that “one can see as many ‘spiritualities’ . . . as there are individual seekers.”4 While undoubtedly true, Elvis Presley’s inherited and changing spirituality does relate to predominant regional patterns. While young Presley can easily be seen as a representative southerner of his time and place, it is hard to make that argument for the last two decades of his life, dominated as they were by the extraordinary success and celebrity that moved him beyond regional to national and international contexts. Nonetheless, his relationship to religious music and southern spirituality makes him a revealing and perhaps even an emblematic figure in southern culture.

The scholarly discussion of spirituality originally came more out of Catholic tradition than the Protestant one that has dominated the American South. The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church defines the term “spirituality” as referring to “people’s subjective practice and experience of their religion, or to the spiritual exercises and beliefs which individuals or groups have with regard to their personal experience with God.” This might include prayer, meditation, contemplation, and mysticism. It notes that certain groups have “a characteristic set of spiritual practices and beliefs” such that “they may be regarded as constituting a ‘school of spirituality,’ ” such as Cistercian spirituality, Carmelite spirituality, or Jesuit spirituality. Reflecting recent changes, the dictionary notes that this usage is now more generalized, “so that there is an increasing interest in ‘lay spirituality,’ ‘married spirituality,’ etc.”5 In this context, religious music should be seen as the essence of a distinctive southern school of spirituality, rooted in particular spiritual exercises and devotional practices.

Consideration of spirituality in a regional context deepens the understanding that religiosity has infused southern culture far beyond the church doors. Presley’s spirituality reflected the significance of the role of spiritual practice. Robert Wuthnow makes a useful distinction between “spirituality,” which he defines as “a transcendent state of being or an aspect of reality,” and the related idea of “spiritual practice,” which he sees as “a more active or intentional form of behavior.”6 Few studies have examined ways in which spiritual practices change during people’s lives and even fewer give attention to ways that American cultural changes affect the meaning of spiritual practices. Spirituality is socially constructed, and Elvis Presley’s evolving spirituality, based in distinctive southern spiritual practices, provides a revealing focus for examining a virtually unexplored area of southern religiosity over several decades in the mid-twentieth century.

OLD-TIME MUSIC—ELVIS’S SPIRITUAL INHERITANCE

Gladys Presley’s favorite singing group was the Louvin Brothers, the harmonizing country-music duo steeped in the South’s religious music, and their experience shows something of a traditional, southern white school of spirituality based in religious music, which Elvis inherited. Born in the 1920s, the Louvins grew up at Sand Mountain, an isolated area in northern Alabama less than two hundred miles from Presley’s Tupelo and part of the same hill-country, predominantly white folk culture. Music was an essential part of individual, family, and community life. In addition to dances and fiddling contests, such specifically religious gatherings as all-day church singings and Sacred Harp singings characterized the culture of the area. Their grandfather was a traditional banjo picker, and their mother sang old, unaccompanied folk ballads, like “Knoxville Girl,” with roots in the British Isles. Their mother’s family in general were active in Sacred Harp singing, a tradition based on songs from a popular songbook of that name from the 1840s that used shape notes, rather than position on the musical staff, to determine pitch. Once popular in New England and other areas of the United States, by the twentieth century shape-note singing came to be associated mostly with southern rural communities. Churches moved beyond its forms as worship music, but periodic singings, often in church buildings, created a “second church” experience as people renewed a traditional Calvinist-inspired faith by singing the old songs the old way. Sacred Harp singing helped to perpetuate a strong strain of Calvinism in the rural South, even as churches themselves softened Calvinism’s rigors through a theology of redemption.

As well as growing up singing Sacred Harp songs, the Louvins participated in other activities that gave structure to this southern school of spirituality. Rural singing schools taught by traveling teachers who would instruct students in religious and other music, for example, became pervasive in the hill-country South. The singing convention also anchored southern spirituality. It gathered together those who wanted to sing new songs, published in small, paperback religious songbooks—which became an important devotional factor—and made accessible older and newer religious songs. Companies in the Tennessee towns of Lawrenceburg and Chattanooga, not far from either the Louvins or the Presleys, used modern, aggressive sales practices to promote their books, including sponsoring professional gospel quartets who sang from the new songbooks. These institutions and practices provided a structure for a southern spirituality rooted in religious music.7

The Louvins lived through the modernization of southern religious music, and the publishing companies were one example of that. The coming of radio in the 1920s and rural electrification of much of the rural South in the 1930s made religious music even more accessible and important to a changing culture. The Louvins heard Sunday morning preaching and everyday hymn singing on their radios. Phonograph records as well became an important source for the Louvins and other southerners in the evolving culture of spirituality in the decades between world wars. When their father visited Knoxville, he would go to the music store and bring home a dozen or so albums, which the family would listen to long into the night, including the mournful ballads of the Carter Family and the up-tempo religious songs of the Chuck Wagon Gang, both enormously popular, early southern recording artists who drew from the traditional musical culture and defined it for a new generation of listeners. Once they started performing, the Louvins themselves became a force in this school of southern spirituality. “We were always ...