![]()

CLAY COUNTY

The Hundred-Year War

![]()

The Incident at the Courthouse

The sun had pushed its way above the jagged hills of Clay County, melting the mists over the waters of the South Fork of the Kentucky River, sucking up the fog from the dark hollows when, on the morning of June 9, 1899, Bad Tom Baker and thirty of his mountain kinsmen and followers rode into the Clay County seat of Manchester, Kentucky. People along the road into town and along the steep street leading to the hilltop courthouse watched with uneasy glances as the silent men rode up Anderson Street, turned and stopped in front of the two-story courthouse where soldiers, members of the Kentucky State Militia, stood in small groups around tents pitched on the courthouse lawn.

The soldiers shifted uncertainly as the horsemen drew up and formed a ragged line on either side of their leader, who sat for a moment, not speaking, looking with what seemed to be amused contempt at the youthful militiamen. He, Thomas Baker, sometimes called Bad Tom, was the reason the soldiers were there, just as the soldiers were the reason he was there. With an unhurried glance right and then left, and a nod as if in approval of what he saw, Baker dismounted, hitched his horse to the top rail of the low fence, and turned toward the courthouse.

Twice in recent months Tom, leader of the Baker clan in its lingering feud with the Howard and White families, had been accused of brutal murders, the most recent the killing of Deputy Sheriff Will White. In keeping with mountain custom, county officials had sent word to Tom, his son James and his brother Wiley to come in and face trial. Tom had declined the invitation, repeating his belief that he could never hope for a fair trial in courts that he said were controlled by his feud enemies, the Howards and Whites. Local lawmen, knowing that the Bakers could summon fifty men in minutes to defend the clan if need be, were not eager to go up on Crane Creek and bring Tom in.

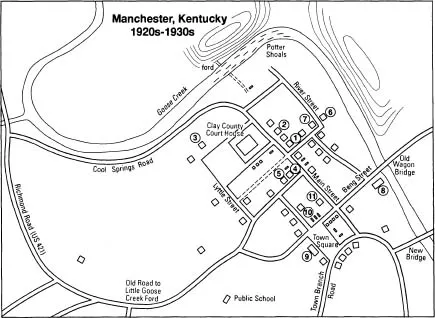

Map 2

Based on information from Jan R. Walters provided by Tom Walters.

1. Bill Marcum house, later a boarding house where Big Jim Howard lived in his last years.

2. Beverly White house, from which Tom Baker was shot.

3. County jail

4. Dr. D.L. Anderson home

5. First National Bank

6. Pitt Stivers home

7. Rev. Francis R. Walters home

8. Livery stable

9. John A. Webb Hotel, owned before 1896 by Calvin Coldiron

10. Dr. Monroe Porter’s drugstore

11. Post Office

But Tom had also sent word that he would come in if Governor William O. Bradley would send troops to protect him and guarantee him a fair trial. He added, however, that he would not be put into “that stinking rathole of a jail”; he demanded a room in the nearby hotel. And he warned that he and his men would surrender their guns only if the Whites and Howards were disarmed first. Col. Roger D. Williams, in charge of the troops, had sent word the previous day that this would be done, and now in the humid morning of the mountain summer, Bad Tom Baker and Colonel Williams faced each other, polite but unsmiling, on the walkway leading to the courthouse.

Whatever he had expected, Colonel Williams confronted no cartoon stereotype of the shifty-eyed, tobacco-stained hillbilly. Almost six feet tall and solidly built (a young woman who once applied to Baker for a teacher’s job described him as “a fine figure of a man”), with dark hair under his slouch hat, a full mustache, and gray eyes that regarded the soldier before him with a level gaze, Bad Tom was no simple ridgerunner. His dark broadcloth suit was rumpled from the ride in from Crane Creek but was in keeping with the styles of the day, as were his white shirt and black bow tie. Standing behind him, his son James and brother Wiley were similarly dressed, in contrast to the rough work clothes of the horsemen leaning on the fence, some holding rifles casually in the crook of their arms, most with long-barreled pistols stuck into their belts.

“Mr. Baker,” said Williams, nodding politely.

“Colonel.”

The officer shifted. He did not relish the role of peace officer.

“I am Col. Roger Williams, Mr. Baker,” he said. “I have been ordered by the court to place you under arrest.”

“Yes,” said Tom, curtly. “I know.”

“I also have orders to bring your son James and your brother Wiley into court.”

Tom half-turned to the two men behind him. “This is them,” he said.

“I’ll have to ask you to surrender your weapons and accompany me into court,” said the colonel. Tom looked at him without moving.

“They said I wouldn’t have to stay in the jail,” he said.

“Yes,” said Williams, “right here, sir.” He led the way to one of the tents pitched on the lawn, furnished with two cots, a lantern, and a table of sorts with a pitcher and wash basin on it. Baker glanced at it, expressionless. The soldiers standing nearby looked nervously at the notorious mountain feudist and his hard-faced followers.

“You’ll be flanked by soldiers to protect you at all times,” Williams continued. Baker nodded curtly, and again Williams had the unpleasant feeling that he was being put into the position of seeking the approval of this accused killer. His men, he knew, assumed that no one would dare attack the army, but he understood the danger in his position, miles from a road or railroad, his inexperienced troops surrounded by hardened marksmen.

“You may have whatever visitors you like, as long as they are not armed,” he said. “We will provide your meals.”

Tom shook his head. “Don’t bother about it. We’ll eat across the street.”

Williams started to object but apparently decided against it.

“I’ll have to ask you for your weapons,” he said. “Your men will have to surrender their weapons when they come on courthouse grounds.”

Tom reached under the tails of his coat and brought out a black .44 caliber revolver and handed it to Williams in an offhand manner.

“Where you putting Jim and Wiley?” he asked bluntly. “I want them with me.”

“I wasn’t told anything about them,” said Williams. “I’ll have to consult Judge Cook.”

Tom looked at him, nodded. “I guess we better go in,” he said. And Williams, again feeling that he was taking rather than giving orders, turned toward the courthouse steps. Before they entered, Tom turned and stepped back toward his kinsmen.

“John,” he called. “Charlie.” Two men pushed their way through the group. “You’re going to have to give up your guns,” he told them. “Just be sure you get them back before you leave for the day. Don’t go out on the streets, out in town, without them. There’ll likely be a lot of people in town, being Saturday. Stay away from Bev White and his dog-shit deputies, hear? And Jim Howard. I don’t know if he’s here. Watch out for him. Tell the boys, any of them need to go back home, do it now before they give up their guns. If they need to go, it’s all right.

“I look for General Garrard to be here directly,” Tom said. “A.C. Lyttle will be the lawyer for Jim and Wiley. The general says he’s got me one named Robertson, but it may be A.C. I don’t know. They’re going to ask the trial be shifted to down at London or Barbourville, and the general says we’ll get it, so we oughtn’t be here more than today. Emily’s coming in this afternoon. If I’m inside, you boys look out after her, take her over to the Potter place.”

The men nodded, looking at the ground. Tom turned and joined the colonel, and the group walked into the courthouse. As they approached the doors leading to the courtroom they passed the office of Sheriff Beverly White, who looked up from behind the counter where already a half-dozen pistols lay, two in holsters. The colonel put three more pistols down and again led the way down the hall. Tom Baker gave no sign that he recognized the sheriff, whose brother Will he was accused of killing. He hesitated only a second when he saw, standing in the doorway of the tax assessor’s office, James “Big Jim” Howard, the man who had killed Tom’s father, Baldy George Baker. After two delays and a hung jury (the jury had reportedly voted 11-1 for acquittal), Howard had been found guilty by a Laurel Circuit Court jury but was free on appeal. Taller than Baker, wide in the shoulder, ramrod straight, well-dressed, and handsome, Big Jim Howard was imposing. For a second he stared without expression at the Bakers. Then a soldier came forward to hold the doors to the courtroom, and Williams and the Bakers went in.

Jim Howard turned and went back into his small but neat office. The day was beginning to heat up, and he opened a window and stood for a minute looking out at the tents and soldiers on the lawn. In front of the line of tents stood the much-talked-about Gatling gun that the troops had brought aboard the special Louisville and Nashville Railway car from Frankfort, loading it with a great deal of sweating and cursing onto a wagon at the station in London for the twenty-five-mile trip over the mountain road to Manchester, the county seat of Clay County and the center of the feud that for half a century had slowly engulfed the county and its people.

Along the walk men milled around the gun, admiring it, laughing at the rumor that either the Howards or the Bakers would bushwhack the troops and capture the gun before the soldiers could haul it back to London. They had already sized up the young city boys and decided that if they had to fight their way out of the county they would have little chance against the feudists.

Shortly before noon a smart, one-horse buggy drew up, two horsemen riding before, two behind, and the Baker clansmen stepped back to make way for the dignified, white-haired man who stepped stiffly down. “All right, get back for the general,” one man said, and the others made way for General Theophilus Toulmin (T.T.) Garrard, hero of the Mexican and Civil wars, former member of Congress and the state legislature, grandson of a governor, and patriarch of the Garrard family that for fifty years had opposed, in commerce and politics and the degrading feud, the Whites and their followers. From his guard-surrounded, lonely, decaying mansion out on Goose Creek, the general had driven into town to lend his support to his Baker followers, just as old Judge B.P. White had come up to the courthouse to help the Howards, long allies of his family, in case of trouble. Now the general nodded his thanks and made his way into the courthouse.

“Tom going to tell us when to come in?” asked one of the men. Another said someone would. Talking quietly among themselves, the men squatted or sprawled on the grass. Several lit pipes. One, without ceremony, stood up and urinated on a tree near the walk, earning the indignant attention of a young trooper.

“There’s a latrine around back,” he said sternly. The man finished urinating, looked at him and said, “Go piss in it, then.” Red-faced, the soldier glared for a moment, then turned away. There was a muttering among the soldiers. The clansmen smirked.

After what seemed a long time a man came to the door of the courthouse and said, “You can come in if you want to,” and the men filed into the courthouse. Inside, a deputy took their guns and placed them on the counter in the sheriff’s office. For a moment it seemed there might be trouble when a young man said he’d be damned if he was going to give Bev White his gun, but an older man standing behind him said, “Come on,” and the man handed it over.

Quietly, not speaking, the men shuffled into the courtroom, filled the long benches. On the bench, on a platform elevated about eighteen inches above the floor, sat stern-faced Judge King Cook, up from Pineville, in Bell County, to fill in for Judge Eversole, who had asked to be excused because of illness in his family. Most people in Manchester believed that Eversole was simply afraid to hold court with both Jim Howard and Tom Baker in town and their families standing by. For that reason, Judge Eversole had asked for troops to keep order, and Judge Cook had underlined that act by forbidding anyone to come into the courthouse armed.

Now Colonel Williams sat conspicuously to one side of the judge as a reminder to anyone tempted to start trouble. Sitting at the table to the left was General Garrard, the two lawyers he had brought from Lexington to help defend the Bakers, and Tom, who turned and watched as his kinsmen trooped into the courtrooms. The judge rapped for order, A.C. Lyttle asked to approach the bench, and the three lawyers and the prosecutor argued quietly for more than half an hour over the defense request to transfer the trial to another jurisdiction. It was after eleven o’clock when the judge told the Commonwealth’s attorney to proceed. For the next half-hour the man argued forcefully that the Bakers could receive a fair trial in Manchester and that if they were as innocent as they claimed, they should be glad to be tried by people most likely to be familiar with the facts.

A.C. Lyttle rose to present the case for changing venue, but Judge Cook interrupted and announced a recess until two o’clock. Grumbling, the Baker followers filed out. They grumbled more loudly when they found that the sheriff’s office was closed and there was no way for them to retrieve their guns. On the walk outside, General Garrard and Tom Baker stood apart from the rest.

“I want to thank you,” said Tom.

“Not at all, not at all,” Garrard replied. “I suppose I should be getting on out home, nothing for me to do now. Too bad we got such a late start, but I think you’ll be able to finish up this afternoon. Lyttle says he has no doubts you’ll get a change of venue; Cook doesn’t want the trial held here, with everybody in town, afraid of what might happen. But you’ll probably have to stay the night here and leave in the morning. I’ll be here before you leave. Try to keep your men from getting into trouble. It’s my guess there are plenty of men around who wouldn’t mind a gunfight.”

Tom, Jim, and Wiley ate dinner at the Potter House, smoked for a while, and returned to the courtroom, but were startled to learn that Judge Cook, after observing the Baker clansmen in the courtroom that morning, saw the possibility of an outbreak that could cost lives and ruin chances for a successful term of court, and ordered the court cleared. The Baker followers were outraged, stormed from the building, then came back to kick on the door to the sheriff’s office, demanding return of their guns. A bailiff came out of the courtroom and told them the guns would be given back as soon as court adjourned. Judge Cook didn’t want any shooting, inside or outside the court.

A.C. Lyttle made a passionate plea for a change of venue, arguing that no man under God’s sun could find an impartial jury in Clay County to try Tom Baker and his kin. He pointed out that the county was under the control of the Whites and Howards, and that violence was sure to erupt if the trial of a Baker for killing a White were held in Manchester, troops or no troops.

Looking at the soldiers and the Baker followers talking and gesticulating outside the courtroom window, Judge King Cook needed no reminder of the truth of Lyttle’s argument. Inside or within gunshot of the courthouse were the heirs of the long, bloody war that had gripped and scarred Clay County almost from the moment of its founding in 1806, when it was carved out of neighboring Floyd, Knox, and Madison Counties and named for Revolutionary War hero General Green Clay, of the famous Kentucky family.

A rugged, scenic recess in the heart of the Cumberland Mountains of the Appalachian range, Clay County seemed doomed to trouble from its beginnings. In the early days the rough terrain made road-building so difficult and costly that settlers could seldom manage more than rocky trails, though every able-bodied man was required to work on the roads or contribute to their construction. This lack of roads helped to isolate them from the mainstream of America as the tide of settlement swept westward, and made it hard to develop trade with the booming towns of Central Kentucky.

And Clay had wealth to trade. The wide, beautiful hills contained some of the finest virgin timber in the eastern United States—beech, oak, poplar, walnut, hickory, chestnut. Under the dark hills lay coal seams whose value had not been guessed. And along the banks of Goose and Sexton Creeks were wells that yielded water rich with salt, that mineral so precious on the frontier.

It was the salt wells that drew the earliest settlers into Clay County. Jim Burchell, taxidermist and amateur geologist from Manchester, believes that Spaniards and possibly Welsh, who some believe were in the country long before Daniel Boone and his kind, were drawn there by Indian tales of great salt deposits. The first settler who made salt there was James Collins, a long hunter who in 1775 tracked some animals to a large salt lick on what is now Collins Fork of Goose Creek, and the following year returned to stake a claim. Word of his discovery spread slowly, partly because of the Revolution but chiefly because no one realized how much salt was there. But by 1800 settlers were beginning to sink the big salt wells along Goose Creek, and the fledgling state of Kentucky considered the salt so valuable that it built the first road into the county to get the salt out. It was not much of a road, but a road.

Considering the isolation of Clay County and the difficulty of transportation, the salt industry grew fairly rapidly. In 1802 there were two wells in the county, with an output of less than 500 bushels a year. By 1845 there were fifteen deep wells—some drilled to depths of a thousand feet—whose waters yielded a pound and a quarter of salt per gallon. With the accompanying furnaces, they were producing 250,000 bushels a year, and with salt selling for a dollar and a half to two dollars a...