eBook - ePub

Hollywood's Indian

The Portrayal of the Native American in Film

- 264 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Hollywood's Indian

The Portrayal of the Native American in Film

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Hollywood's Indian by Peter C. Rollins, John E. O'Connor, Peter C. Rollins,John E. O'Connor in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Film History & Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Absurd Reality II

Hollywood Goes to the Indians

When McMurphy, the character portrayed by actor Jack Nicholson in the fivefold Oscar-winning movie One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975), prods a mute Indian Chief (played by Indian actor Will Sampson) into pronouncing “ahh juicyfruit,” what the audience heard was far removed from the stereotypical “hows,” “ughs,” and “kemosabes” of tinsel moviedom. “Well goddamn, Chief,” counters McMurphy “And they all think you’re deaf and dumb. Jesus Christ, you fooled them Chief, you fooled them.… You fooled ’em all!” In that simple and fleeting scene, a new generation of hope and anticipation was heralded among Native American moviegoers. Long the downtrodden victims of escapist shoot-’em-and bang-’em-up Westerns, Native Americans were ready for a new cinematic treatment—one that was real and contemporary.

Native Americans had grown accustomed to the film tradition of warpaint and warbonnets. When inventor Thomas Alva Edison premiered the kinetoscope at the 1893 Chicago Columbian World’s Exposition by showing the exotic Hopi Snake Dance, few would have predicted that this kind of depiction would persist into contemporary times. Its longevity, though, is explained by the persistence of myth and symbol. The Indian became a genuine American symbol whose distorted origins are attributed to the folklore of Christopher Columbus when he “discovered” the “New World.” Since then the film industry, or Hollywood, has never allowed Native America to forget it.

The Hollywood Indian is a mythological being who exists nowhere but within the fertile imaginations of its movie actors, producers, and directors. The preponderance of such movie images have reduced native people to ignoble stereotypes. From the novel, to the curious, to the exotic, image after image languished deeper and deeper into a Technicolor sunset. By the time of the 1950s John Wayne B-Westerns, such images droned into the native psyche. The only remedy from such images was a laughter, for these portrayals were too surreal and too removed from the reservation or urban Indian experience to be taken seriously.

In the face of the exotic and primitive, non-Indians had drawn on their own preconceptions and experiences to appropriate selectively elements of the Indian. The consequent image was a subjective interpretation, the purpose of which was to corroborate the outsiders viewpoint. This process is called revisionism, and it, more often than not, entails recasting native people away and apart from their own social and community realities. In an ironic turnabout, Native people eventually began to act and behave like their movie counterparts, often in order to gain a meager subsistence from the tourist trade. In that sense, they were reduced to mere props for commercial gain.

However, beginning in 1968, with the establishment of the American Indian Movement (AIM), much of this misrepresentation was to change. The occupation of Alcatraz Prison in 1969, of the Bureau of Indian Affairs headquarters in 1972, and of Wounded Knee in 1973 followed in rapid succession. These were bloody struggles that many Native Americans consider to be every bit as profound as the political dissolution of the Soviet Union or the dismantling of the Berlin Wall. They served to bring the attention of the modern Native’s plight to mainstream America.

Such activism did not escape the big screen. Hollywood scriptwriters jumped onto the bandwagon with such epics as Tell Them Willie Boy Is Here (1969), Soldier Blue (1970), A Man Called Horse (1970), Little Big Man (1970), Return of a Man Called Horse (1976), and Triumphs of a Man Called Horse (1982). Little Big Man in fact, established a milestone in Hollywood cinema as the result of its three-dimensional character portrayal of Sioux people. This included what is perhaps one of the finest acting roles ever done by an Indian actor, Dan George, who portrayed Old Lodge Skins.

Indian activism, however, was subtly transformed toward unmitigated militancy with the production of Vietnam War-based movies. Movies such as Flap, or Nobody Loves a Drunken Indian (1970), Journey Through Rosebud (1972), Billy Jack (1971), The Trial of Billy Jack (1974), and Billy Jack Goes to Washington (1977) revised the message of Indian activism to an even more bizarre level. Native Americans were portrayed as ex-Vietnam veterans whose anti-American behavior despoiled their common sense. Herein was the ultimate blend of aboriginal nitro and glycerin.

The first premonition of “Red Power” decay came shortly after actor Marlon Brando set up a cameo for the Apache urban-Indian actress Sacheen Little Feather as the stand-in for his rejection of the 1973 Best Actor Academy Award for The Godfather. Later in 1973 “Ms. Littlefeather,” as she was called, earned herself even more notoriety as the Pocahontas-in-the-buff activist in a nude October spread in Playboy. Within the context of puritanical America, this unfortunate feature became the ultimate form of image denigration.

Around this time, the famous “Keep America Beautiful” teary Indian (Cherokee actor Iron Eyes Cody) and the Mazola Margarine corn maiden (Chiricahua Apache actress Tenaya Torrez) commercials were being run on television. These stereotyped images and their environmental messages etched themselves indelibly into the minds of millions of householders. The “trashless wilderness” and “corn, or what us Indians call maize” became the forerunners of the New Age ecology movement.

Because such imagery was so heavily invested in American popular culture, gifted Native actors like the Creek Will Sampson (1935–1988) and Salish Chief Dan George (1899–1982) continued to be relegated to second billings in films like The Outlaw Josey Wales (1976, also starring Navajo actress Geraldine Keams), and Buffalo Bill and the Indians, or Sitting Bull’s History Lesson (1976). The same fate befell others like Mohawk actor Jay Silverheels (1912–1980), who was widely recognized as Tonto in The Lone Banger and who went on in 1979 to be the first Native actor awarded a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.

In spite of these shortfalls, the Native presence was posed for a major, albeit short-lived, breakthrough in the film industry. The Indian Actor’s Workshop was begun in the early 1960s and was followed in turn by the establishment of the American Indian Registry for the Performing Arts in the 1980s. Both organizations were committed to promoting Native actors in Native roles. This momentum, which came as a result of advocacy among the ranks of senior Native actors, slowed to a lumbering pace with the untimely deaths of Sampson, George, and Silverheels. It left an enormous vacuum within the professional ranks of the Screen Actors Guild.

So, in spite of Hollywood’s attempts to “correct the record,” the movies of this period all basically had one thing in common—”Indians” in the leading role were played by non-Indians. A few films like House Made of Dawn (1987, starring Pueblo actor Larry Littlebird), When the Legends Die (1972, featuring “the Ute tribe”), and The White Dawn (1975, featuring “the Eskimo People”) attempted to turn the tide. Unfortunately, the films earned the most meager of receipts. This in turn guaranteed that a movie cast by and about Native Americans was a losing investment. Producers and directors continued to seek the box-office appeal of “name recognition” instead. When the casting really mattered—as in the film Banning Brave (1983, starring Robby Benson), which was about the life of the Sioux sprinter Billy Mills, a 1964 Tokyo Olympic gold metalist—non-Indians continued to preempt Indian actors. Ditto for Windwalker (1980), whose lead Indian part was preempted by a British actor, Trevor Howard.

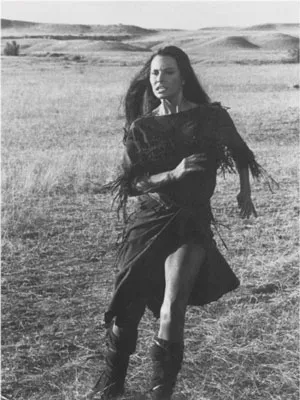

The absurdity of casting non-Indians reached its pinnacle in the mid-1980s. In the opening sequence of The Legend of Walks Far Woman (1984), a legendary Sioux woman warrior, Walks Far Woman—played by buxom Raquel Welch—plummets over a hundred-foot precipice and stands up looking rather ridiculous and totally unscathed. In Outrageous Fortune (1987), actor George Carlin continues the brainless tradition by playing a hippie Indian scout. “That’s my main gig,” exclaims Carlin as he badgers actresses Bette Midler and Shelley Long,—”genuine Indian shit. …”

By the early 1990s, that “genuine Indian shit” had come full circle. What should have happened, a sequel to Cuckoo’s Nest—a full-featured realistic and contemporary performance about and by an Indian—occurred with Powwow Highway (1989). Given an unexpected second life as a rental video, the acting of a then-unknown Mohawk Indian actor, Gary Farmer, came closest to revealing the “modern” Indian-self, much in the same light that Indian producer Bob Hicks attempted to pioneer in Return to the Country (1982). Yet although Farmer, as Philbert Bono, is believable to Indians and non-Indians alike, he is still cast as a sidekick to the main actor, A. Martinez. In this film a Vietnam vet, Buddy Red Bow, trails through a cultural and spiritual reawakening while Bono is reduced to a kind of bankrupt Indian trickster. The problem with Powwow Highway is that it suffered from a predictable activist storyline that froze solid sometime in the early 1970s. In spite of this flaw, Hollywood was suddenly enamored of the novelty of the multicultural drumbeat—Indians played by Indians.

Another variation on this Hollywood multicultural love affair was Thunderheart (1992, starring Oneida actor Graham Greene). Although technically superior to another B-movie Journey Through Rosebud (1972), it managed to rehash a basic plot of the naive half-breed who stumbles upon reservation graft and corruption. But the original conception of this ploy had already been hatched in Tell Them Willie Boy Is Here (1969). In that film, a Paiute Indian returns to the reservation to expose the evil machinations of the non-Indian agent.

In Thunderheart, the plot is updated so that the blame is shifted to corrupt tribal government officials. Its screenplay was loosely based on the real-life murder of a Native activist, Anna Mae Aquash (played by Sheila Tousey, a Menominee of the Stockbridge and Munsee tribes). In spite of its casting achievement, the film nonetheless went on to demonstrate that a non-Native actor cast as a “wannabe” can still walk away completely unscathed from an unpalatable and unresolvable situation.

Figure 1.1. Sex symbol (Raquel Welch) as Indian: Non-Natives pitched to white audiences? Courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art/Film Stills Archive.

But the finest example of this wannabe syndrome, as well as being one of the premier reincarnation film of all times, is Dances With Wolves. Winner of seven Academy Awards, including Best Picture for 1990, the story is a remarkable clone of Little Big Man (1970). Both films used the backdrop of the historic Lakota and Cheyenne wars. Both typecast the Lakota and Cheyenne as hero tribes, victimized by their common archenemies, the U.S. Cavalry, and “those damn Pawnees!” However, unlike Little Big Man, which reveled in its pointed anti-Vietnam War message, Dances With Wolves was devoid of any redeeming social merits. Rather, it was apolitical and subconsciously plied its appeal by professing a simple New Age homily about peace and Mother Earth.

Nonetheless, as a result of its box-office appeal, Dances With Wolves accomplished what few other Western films have done. It ushered forth a new wave of Indian sympathy films and unleashed another dose of Indian hysteria among revisionist historians. For example, films like War Party (1990) and Clearcut (1991) attempted to place the Indian into a contemporary framework. But unlike Powwow Highway, the plots of these films were as surreal and bizarre as a Salvador Dali painting. Rather, both films were, more or less, classic in the manner in which they were depicted as psychodramas. Native actors finally got to act out unabashed their colonially induced angst, although that depiction still gets mixed reviews even among Native moviegoers.

Not to be left out, the TV industry also attempted to remake bestsell-ing novels into prime-time movies. ABC-TVs The Son of the Morning Star debuted to uninspired TV viewers in 1991. Lonesome Dove (1991) fared a little better, and there was great anticipation for the made-for-TV screen adaptation of Modoc writer Michael Dorris’s The Broken Cord (1992). Unfortunately, TV producers preempted Native actors with non-Indian actors and, as a consequence, the staged overall effect remained dull and staid.

The most contentious example of a non-Native production was yet to come. It occurred in the screenplay adaptation of mystery novelist Tony Hillermans Dark Wind (1992). Non-Native actor Lou Diamond Phillips was cast as the central character, Navajo policeman Chee, while the six-foot-plus Gary Farmer was miscast as a five-foot-tall, more or less, Hopi policeman. Both the odd combination of actors and the spiritually offensive aspects of the storyline resulted in official protests being lodged by both the Navajo and Hopi tribal governments. Fearing legal reprisal, its makers pulled the film out of the American market and floated it among the die-hard, Karl May-reared moviegoers of Europe instead.

But it was now 1992, and this quincentennial celebration was supposed to be a banner year for indigenous peoples. The reality of political correctness, however, turned it into a categorical revisionist bust instead. Neither of the celebratory films 1492 nor Christopher Columbus: The Discovery broke any box-office records or changed any minds about Native people. In fact, if it proved anything, it really did reinforce the old adage that immortal gods don’t shit from the sky. Even though attempts were made to draw moviegoers to the exotic pull of the undiscovered New World, the mind’s eye proved far more compelling.

Hollywood continued to remain mired in mythmaking. If any strides were to be had, they usually resulted from the work of a few well-placed Native consultants. In this manner, Native playwrights and cultural experts were finally given the opportunity to add a tribal precision and to insert snippets of real Native languages, rather than the usual made-up ones.

The Black Bobe (1991) was one of the first representatives of such an attempt. A story about a Jesuit missionary among the warring Huron, Algonquin, and Iroquois tribes, it attempted to debunk the idea that all Native people lived among one another in blissful harmony. Its mistake, though, was to depict a contemporary pan-Indian powwow in 1634 and to insinuate that the only kind of Indian sex was doggie-style intercourse. Another film inspired by Native consultants was the forgettable Geronimo: An American Hero (1993). The portrayal of Geronimo by Wes Studi attempted to revamp the warring Apache into a gentler and kinder mystic chief. But the fact of the matter is that because Geronimo has been cast in so many fierce roles, everyone has genuinely forgotten how to deal with the humanization of such a legend. In spite of all their efforts, Geronimo remains, well, Geronimo. ABC-TVs own cartoon rendition of Geronimoo in the Cowboys of Moo Mesa was far more interesting and honest.

The most intriguing effort of this cycle, however, was the The Last of the Mohicans (1992). This film was a fusion of fact and fiction. The fact was supplied by Native consultants, the fiction by James Fenimore Cooper. At the symbolic center of this film was American Indian Movement activist Russell Means. Means was cast as Chingachgook, a marathon-running sidekick of Hawk-eye, played by non-Indian Daniel Day-Lewis. Although Cherokee actor Wes Studi, playing the Huron villain Magua, ultimately stole the show, the cooptation of a militant AIM founder was the cinematic milestone.

Means’s presence resounded with the same activist overtones found in his predecessor, Sacheen Little Feather, a full two decades earlier. Both came to uncertain terms with Hollywood and both were hopelessly...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1. Absurd Reality II: Hollywood Goes to the Indians

- 2. The White Man’s Indian: An Institutional Approach

- 3. The Indian of the North: Western Traditions and Finnish Indians

- 4. Trapped in the History of Film: The Vanishing American

- 5. The Representation of Conquest: John Ford and the Hollywood Indian (1939-1964)

- 6. Cultural Confusion: Broken Arrow

- 7. The Hollywood Indian versus Native Americans: Tell Them Willie Boy Is Here

- 8. Native Americans in a Revisionist Western: Little Big Man

- 9. Driving the Red Road: Powwow Highway

- 10. “Going Indian”: Dances With Wolves

- 11. Deconstructing an American Myth: The Last of the Mohicans

- 12. Playing Indian in the 1990s: Pocahontas and The Indian in the Cupboard

- 13. This Is What It Means to Say Smoke Signals: Native American Cultural Sovereignty

- Bibliography

- Contributors

- Index