eBook - ePub

Helen Matthews Lewis

Living Social Justice in Appalachia

- 276 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Helen Matthews Lewis

Living Social Justice in Appalachia

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Publisher

The University Press of KentuckyYear

2012Print ISBN

9780813145204, 9780813134376eBook ISBN

9780813140063CHAPTER 1

The Making of an Unruly Woman, 1924–1955

I had a grandmother who loved to argue with preachers. She was Scotch Presbyterian, as she said, and she loved the Baptist preachers to come to the house so she could argue with them about predestination. And I see myself as I get older being more like this grandmother, who speaks back at things and won’t shut up and says the wrong thing at the wrong time.

—Helen Matthews Lewis, quoted in Lori Briscoe et al., “Unruly Woman: An Interview with Helen Lewis”

Helen Matthews Lewis grew up, attended college, became a social justice activist, and married in Georgia. She both loved and worked to change the land-based society that shaped her formative years. As she learned and developed, Georgia developed and changed, too. Urban growth and rural poverty, populism and progressivism, religious conservatism and religious radicalism, racial hatred and racial justice, traditional gender roles and new opportunities for women, galvanized her and her home state from the mid-1920s through the mid-1950s.

Helen’s roots in Georgia run deep and shape many of her lifelong views and values. She grew up knowing that two of her great-grandfathers fought for the Confederacy during the Civil War. She saw how Georgia, like other southern states, enforced a rigid system of segregation, denying African American citizens their basic rights to vote, own property, and gain high-quality education. As a child, Helen recognized the power of racism. While still a young girl, she witnessed her father’s kindness and respect for a Negro neighbor, but she also witnessed the effects of a memorable incidence of racially inspired community violence.

Growing up in rural Georgia meant that she understood rural poverty. Although her family was not poor, the town where she lived did not yet have a public water system or electricity. By the late 1920s, when she was a girl, the boll weevil had decimated the state’s cotton economy, forcing many farmers to become tenants or sharecroppers. Many rural Georgians experienced structural poverty long before the Great Depression, which deepened, rather than caused, the economic inequality she critiqued as a young college student.

She also became keenly aware of the role of women and saw how women could claim power in a male-dominated society and how they could be punished for what were considered social transgressions. One grandmother, Mary Ida Dailey Matthews, the Scotch Presbyterian who argued with Baptist ministers, chopped down a family member’s moonshine still. Another grandmother, Jane Victoria Harris, birthed a daughter without being married and lived the rest of her life in isolation and denial.

Despite, or perhaps because of, Mary Ida’s argumentative Presbyterianism, Helen became more concerned with the power of religion to advance social justice rather than becoming attached to a particular denomination or doctrine. In 1941 Helen enrolled in Bessie Tift College, a private Baptist women’s school in Forsyth. There, she heard Clarence Jordan preach his Cotton Patch Gospels. A homegrown social justice activist and Baptist theologian, Jordan taught economic justice and racial reconciliation by retelling New Testament scriptures in “Cotton Patch” versions, using language and settings familiar to rural listeners. Forty-seven years later, Helen vividly recalls the transformative impact Jordan’s social justice gospel stories had on her.

While Helen studied at Bessie Tift, the United States entered World War II. As in other historical time periods, war accelerated the economic, social, and cultural changes already under way. Thousands of women went to work in greater numbers than ever before as men entered the armed services. Women also joined the armed services, swelling the numbers of WACs and WAVES. Although federal spending on the war effort began to end the Depression nationwide, Helen no longer had the financial resources she needed to continue her college studies and temporarily left school in 1942.

In 1943, Helen enrolled in Georgia State College for Women (GSCW), a public four-year liberal arts institution. Many of her teachers had been suffragettes, helping to win women’s right to vote in 1920. At GSCW, Helen learned that women could be leaders. She worked with her classmate Mary Flannery O’Connor on the 1945 yearbook and became the yearbook editor in 1946. Helen also became an activist, speaking out against economic injustice and joining the Young Women’s Christian Association’s (YWCA’s) national campaign against racism. Helen’s story of participation in the YWCA provides new insights into understanding the importance of this organization in the rural South.

When Georgia became the first state to allow eighteen-year-olds to vote, Helen joined the GSCW League of Women Voters. In 1946, with eighteen-year-olds going to the polls for the first time, Helen, now a graduate, moved to Atlanta to take part in the “Children’s Crusade,” a statewide effort mobilizing young voters to support a progressive candidate for governor. A photograph in the New York Times pictures her among the young leaders in the campaign. The progressive candidate lost, but Helen maintained what became a lifelong commitment to political engagement, human rights, and social justice activism.

Encouraged by GSCW faculty, she entered graduate school at Duke University. There she met Judd Lewis, a graduate student in economics. When she decided to discontinue her studies and return to Atlanta, he enrolled at Emory University there. They married in 1947, Helen envisioning “an egalitarian partnership marriage.” She continued her social justice activism after her marriage. While he attended classes at Emory, she was arrested for participating in an interracial event in Atlanta sponsored by the YWCA.

When Judd accepted a job in Virginia, Helen entered a master’s of arts program at the University of Virginia. In preparing her master’s thesis, she analyzed Gunnar Myrdal’s influential 1,500-page-book published in 1944, An American Dilemma: The Negro Problem and Modern Democracy. Extending Myrdal’s groundbreaking work, her thesis, “The Woman Movement and the Negro Movement: Parallel Struggles for Rights,” points to similar social and economic barriers facing both African Americans and women, predating the civil rights and the women’s movements of the 1960s, as well as later postmodern theoretical constructs of intersectionality. Demonstrating her synthetic analytical skills and commitment to practical applications, she provides both a theoretical and a common-sense basis for alliances and cross-organizing between the two groups.

After Helen left Georgia, she did not live there again for nearly fifty years. Yet her knowledge of rural life formed during her youth in Georgia, the deep religious faith that inspired her commitment to social justice, and the conviction that she, as a woman, must take action against racism and economic exploitation shaped the rest of her life.

Family Memories

I was born in a little place out in the country from Nicholson, Georgia, which is 12 miles north of Athens in Jackson County. My father was a farmer when I was born, and he passed the test during the depression and became a rural letter carrier, which was wonderful because he had a job. So we were well off because he was a mail carrier. (“Unruly Woman: An Interview with Helen Lewis”)

My grandmother on my father’s side was Mary Ida Dailey. She was the daughter of James Monroe Dailey, a Confederate veteran. People always said, “he was so mean he didn’t even die at Shiloh.” After the war, he spent much of his time sitting around the courthouse with other veterans telling war stories. He apparently was a moonshiner and taught at least one of his sons the craft. Mary Ida Dailey married Daniel Presley Matthews, and their son Hugh Presley Matthews was my father. Mary Ida played the organ at the Presbyterian Church, and she strongly opposed drinking moonshine. The story is that she chopped up a still my [d]ad’s brother was building. Mary Ida was the Scotch Presbyterian grandmother who liked to argue with the Baptist preachers.

My grandmother on my mother’s side was Jane Victoria Harris, and the family called her Vicki. Vicki wasn’t married when she had my mother, Maurie Harris. Maurie wasn’t allowed to call Vicki her mother, and she had to pretend to be the daughter of her grandmother Martha Harris. Vicki became a sort of recluse, staying in her room and smoking Asthamador cigarettes.

After Hugh Matthews married Maurie Harris, they lived in a rural community outside Nicholson. Then they moved into town when I was probably about one or two years old. There were about 300 people in the town, and it had a post office and a train came through every day. There wasn’t any electricity, paved roads, or water systems, though. (Unpublished correspondence with Judith Jennings, 2010)

I remember experiences with race relations when I was a child that made me start thinking. My father was a farmer and a rural letter carrier. He took me out to this black community in the country, which was on his mail route. He said he wanted me to meet the most educated man in the county, and it was a black schoolteacher and preacher who did calligraphy. My father got him to write my name on a card because he was intrigued with his handwriting you know, seeing it as a mail carrier. It was just a very impressive thing that here was the most educated man in the county, and my father took me to meet him. I saved that little card for years. Later that same man came to my house to see my father—I must have been seven or eight years old—and he, as black folks did, came to the back door. My mother was in the front room with some women, quilting or something, and I ran to her and said, “Mr. Rakestraw is at the door,” and the women laughed because you weren’t supposed to call a black man “Mister.” And I was so shamed by that. You know, as a child to be laughed at is a terrible thing. (“You’ve Got to Be Converted: An Interview with Helen Matthews Lewis”)

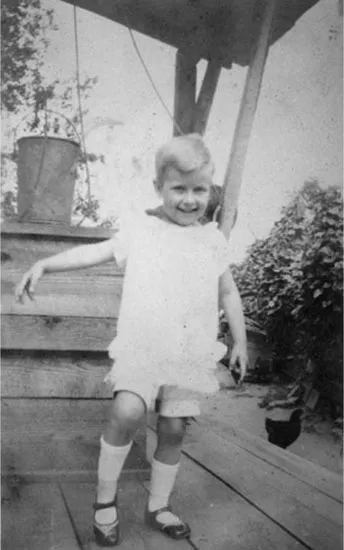

Helen at age four, in 1928

But then when I was ten years old, we got transferred to Cumming, Georgia, which is in Forsyth County, the county where there were no blacks at all. They had a bad race riot in the 20s and had run out all of the African American population and had lynched several and hung them around the courthouse. I heard these stories. And I went to people’s houses that had gravestones from the black cemetery—they’d dug them up and took them home and used them for flagstones. So I had grown up in a community that was just old-timey south, complete segregation and all that. But before I got to Cumming, I was not familiar with hostility. My father was very kind to everybody, blacks, whites, whatever, on his route. I’d never seen the signs of hostility that I saw when we moved to Cumming. And to hear these stories was just horrible. I had a music teacher who brought a black woman with her, who had been with her family for years, an old woman. And they had lived together ever since she had grown up. A group of men came with torches and stuff and made her get up in the middle of the night, and they took that woman out of the county, wouldn’t let her stay in the county, so the black woman had to be taken back to Alabama. So things like that just made me aware of real racism and real violence against blacks. (“Unruly Woman: An Interview with Helen Lewis”)

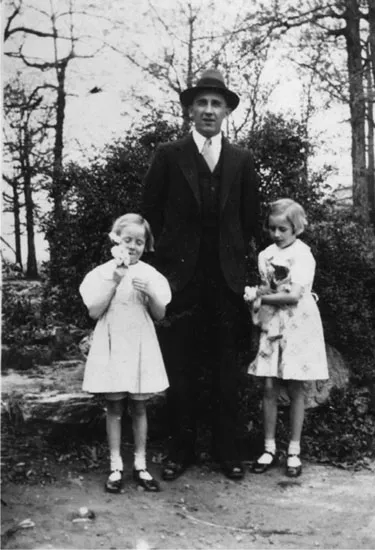

Helen (right) with her father, Hugh Matthews, and her sister, JoAnn, in the 1930s

Helen (right) with her mother, Maurie Harris Matthews, and her sister, JoAnn, in the 1930s

Radicalization and World War II

In 1941, Helen entered Bessie Tift College for Women. Founded in 1849 as the Forsyth Female Collegiate Institute, it became Monroe Female College after the Civil War. In 1907, the school was renamed for Bessie Willingham Tift (c. 1861–1936), an alumna, community leader, and wife of businessman Henry Tift (1841–1922).

As part of the Georgia Baptist Convention, the college welcomed presentations by visiting preachers, such as Clarence Jordan. Like Helen, Georgia-born Clarence Jordan (1912–1969) grew up witnessing economic disparity and racial animosity between African Americans and whites. As a preacher, Jordan delivered his Cotton Patch Gospel sermons in small towns and rural areas across the state. In 1942, he helped establish Koinoinia, a Christian community in which members pooled their resources, treated all persons as equals regardless of race or class, and learned new farming techniques to increase production and profit and help break the cycle of poverty for local families (see Andrew S. Chancey, “Clarence Jordan [1912–1969]”).

I was converted by Clarence Jordan. There is no doubt about that. I was 17 years old, a freshman at Bessie Tift College, a little Baptist school in Forsyth, Georgia, and we had required chapel. All these preachers and people would come and talk to us. One day this young preacher came, 1941 or ’42—it was either the fall or the spring. He had just finished going to Baptist seminary and was starting this interracial farm in rural Georgia called Koinoinia. And he tells us about it, what he’s going to do, and he retold the story of the Good Samaritan, only it was his Cotton Patch version. This man was going down the road and gets beat up by thieves and is left bloody on the side of the road. And the first car that comes by is a preacher, and he’s hurrying off to church, and he sees the poor man beside the road, and he’s practicing up on his sermon, to get them to come up and get saved that night. And he says, “Oh that poor fellow, but I don’t have time. I’ve got to get to church.” Then the next person is the choir leader and the person is so-and-so—you know he goes through these—and finally this old black man, he’s riding down the road in his wagon and he sees him. He gets out, he bandages him up, he puts him in his wagon, and he takes him down to town and tries to put him in the hospital, and they won’t let him in because this black man has brought him in. So he takes him down into “niggertown” where there’s no lights and there’s no pavement, and there’s holes in the road, you know. And he’s the Good Samaritan.

I’m sitting there listening to this man, and it’s kind of like, “My God that is it, that is it! This is the story. This is it!” And there’s no going back after that. I mean it just turned my mind. From then on. (“You’ve Got to Be Converted: An Interview with Helen Lewis”)

The United States entered World War II after the bombing of Pearl Harbor in December 1941. In the spring of 1942, in the European theater of the war, Germany bombed the cathedral cities of Britain, the United States’ main ally. Helen published this brief poem in the college newspaper.

The Campus Quill

Bessie Tift College

April 30, 1942

Two Stories Told in

England, sirens, signals, darkness,

Planes, terror, fright, fears,

Bombs, fire, shells, destruction.

Pain, death, silence, tears.

America, music, singing, laughter

Lights, gladness, fun, thrill,

Parties, rides, school, frolic,

Work, play, peace, good will.

In Georgia, as in other southern states, thousands of men and women joined the war effort. Federal defense money stimulated the national economy and funded new industries in Georgia and other southern states. As men entered the armed forces, large numbers of women, in Georgia and across the United States, went to work outside the home for the first time. Helen went to work, too, leaving Bessie Tift College in 1942 to become a wage earner.

Helen reentered college in 1943, enrolling in Georgia State College for Women (GSCW) in Milledgeville during a new era in Georgia politics. Before 1942, Populist Democrat Eugene Talmadge (1884–1946) dominated the state....

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1. The Making of an Unruly Woman, 1924–1955

- 2. Breaking New Ground, 1955–1977

- 3. Local to Global, 1975–1985

- 4. Participatory Research, 1983–1999

- 5. Telling Our Stories, 1999–2010

- The Final Word

- Chronology

- Bibliography

- List of Contributing Activists and Scholars

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Helen Matthews Lewis by Helen M. Lewis, Patricia D. Beaver,Judith Jennings in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.