- 344 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

A Military History of China

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access A Military History of China by David A. Graff, Robin Higham, David A. Graff,Robin Higham in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Chinese History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

ONE

Introduction

Armed conflict has always played an important role in Chinese history. Most of China's imperial dynasties were established as a result of success in battle, and the same may be said of the Nationalist (Guomindang KMT) and Communist regimes in the twentieth century. Periods of dynastic decline were marked by great peasant rebellions, and the collapse of central authority repeatedly gave rise to prolonged, multicornered power struggles between regional warlords.

Questions of military institutions and strategy have always occupied a prominent place in Chinese political thought, and the armed confrontation between the sedentary Chinese state and the nomadic peoples of the Inner Asian steppe was one of the most fundamental themes of Chinese history prior to the twentieth century.

China's modernization efforts in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries were stimulated by repeated defeats at the hands of the Western powers (and later Japan), beginning with the Opium War of 1839-1842, and by the need to respond to the challenge of domestic rebellions such as that of the Taipings (1850-1864). Indeed, it is arguable that the pursuit of “wealth and power” has been a common denominator of all Chinese regimes from the twilight of the Qing dynasty to the People's Republic (PRC) in the post-Deng era.

In spite of this history, the existing literature has tended to neglect or downplay the role of war and the military. Works on premodern China have emphasized (and reflected) the Confucian pacifism and antimilitary bias of the scholar-official class, while the literature on the nineteenth and twentieth centuries gives pride of place to intellectual, cultural, and political developments. The English-language literature on Chinese military history, ancient or modern, is extremely limited; for premodern China in particular, there is only a handful of books, several of which are now out of print. This volume is intended to fill the gap by offering a wide-ranging overview of the major themes, issues, and patterns of Chinese military history, from the first millennium B.C.E. to the present day. It is designed to provide nonspecialists and newcomers to the subject with basic orientation in fifteen key areas, and each chapter concludes with suggestions for further reading and research.

THE LAY OF THE LAND

The People's Republic of China covers roughly the same land area as the United States, and is somewhat larger than Europe (from Moscow west to the Atlantic). In contrast to the United States and Europe, however, China is not richly endowed with arable land. Most of the country's territory is mountain, desert, or arid plateau, and there is no counterpart to the vast arable expanse of the American Midwest. The largest zone of flat, fertile land, the North China Plain along the lower reaches of the Yellow River, is only a little larger than than the combined land area of Illinois and Iowa. In southern and western China, arable land (and human population) is concentrated in the much smaller river valleys and coastal lowlands. Population is especially sparse in the vast, arid western territories of Xinjiang, Tibet, and Qinghai, which account for nearly half of China's total land area. The country's highest mountains are found in the far west, in the Himalaya and Pamir ranges along the fringes of the Tibetan plateau, and the greatest rivers, the Yellow and the Yangzi, flow eastward from the Tibetan highlands to the Pacific Ocean. These western territories were little touched by Chinese settlement until very recent times. Together with the Gobi Desert in today's Mongolia, they formed an all but insurmountable barrier to the westward and northward expansion of the sedentary, agricultural lifestyle of the Han Chinese.

For most of China's history, these western and northern territories were left in the hands of peoples whose languages, cultures, and ways of life were dramatically different from those of their Han neighbors. Some, such as the Iranian and Turkish oasis dwellers of Xinjiang and the Tibetans of the Yarlung Zangbo (Brahmaputra) valley, were small-scale agriculturalists, but the dominant mode of livelihood was pastoral nomadism. The outer regions were linked to the Chinese heartland by the exchange of horses and other livestock for the products of China's farmers and artisans, including grain, silk, and metalware. Trade in luxuries extended even farther, along the fabled Silk Road that connected China with the Middle East and the Mediterranean world. Given the vast distances, harsh landscapes, and tough customers along the way, however, there was very little direct contact between the two ends of the Eurasian landmass before Europeans found their way to China by sea in the early years of the sixteenth century.

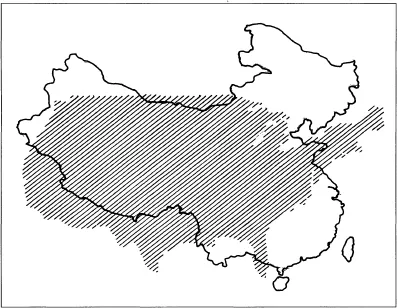

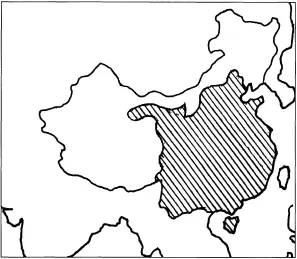

Map 1.2 Relative size of China and the 48 contiguous United States. Adapted by Don Graff based upon Interpreting China's Grand Strategy, Michael D. Swaine and Ashley J. Tellis (Santa Monica, CA: Rand Corporation, 2000)

The territory of today's China can be divided into two zones. The first, “China proper,” was and is densely populated, agricultural, and inhabited mainly by the Han majority; in imperial times its people were ruled directly by the Son of Heaven. The second zone consists of Tibet, Qinghai, Xinjiang, Inner Mongolia, and the three Manchurian provinces; in earlier times this zone also included the territory that is now the independent republic of Mongolia. These lands were (and in some cases still are) very sparsely populated and inhabited by non-Han ethnic groups. At some times in Chinese history these areas paid tribute to the Middle Kingdom and were treated as vassal states; at other times, however, they were fiercely independent and threatening. The power of China in this region has fluctuated greatly over the centuries. The Former Han and Tang dynasties dominated Xinjiang, but Song and Ming did not. Tibet was first attached to the empire by the Mongol Yuan dynasty, but recovered its independence when the Yuan gave way to a new native Chinese dynasty, the Ming. Today's PRC owes its shape largely to the Manchus, who conquered China and established the Qing dynasty in 1644. They brought their own homeland, Manchuria, into the empire, and went on to subdue Mongolia, Tibet, and Xinjiang. Of this Qing legacy only “outer” Mongolia has been lost, primarily as a result of Russian pressure in the early part of the twentieth century.

The theater in which Chinese military history was acted out included not just the territory of today's China (and Mongolia), but covered a vast, subcontinental region of East Asia. The Korean peninsula was administered as an integral part of the Han empire, and was the scene of Chinese military interventions by the Sui and Tang dynasties during the seventh century, by the Ming dynasty in the 1590s, by the Qing in the 1890s, and by the Communists in the 1950s. Northern Vietnam, including today's Hanoi, was ruled by the Qin, Han, and Tang dynasties, and Chinese armies sometimes penetrated even farther south. Han and Tang armies pushed deep into what is now the territory of the former Soviet republics of Central Asia. Mongol-led forces based in China invaded Japan, Burma, and Java in the thirteenth century, and a Qing army marched into Nepal in the 1790s. In the first half of the fifteenth century the Ming “treasure fleets,” led by Zheng He and his associates, explored the Indian Ocean littoral, and in the last three decades the People's Republic has been striving to establish its military dominance in the South China Sea. In periods when China was united and strong, most military encounters took place along the periphery as the country's rulers sought to assert their suzerainty over neighboring states and peoples. During periods of division and civil war, on the other hand, the locus of most military action was the densely populated heartland of “China proper.”

RESOURCES AND INFRASTRUCTURE

In ancient and imperial times, the Chinese heartland was richly endowed with the resources needed to support military endeavors. First and foremost among these resources was China's large population, recorded at more than 56 million by the Han census of 157 C.E., when the population of the Roman Empire was not more than 46 million. During the Song period China's population rose to an estimated 120 million, and between 1650 and 1850 it is believed to have tripled to 410 million.1 These numbers made it possible for the country's rulers to maintain very large military establishments, nearly a million men in the early ninth century and possibly as many as four million under the late Ming. The vast majority of the people, however, were farmers who provided the grain that was needed to feed the troops. When necessary they could be pressed into service as porters for the army, and as corvée laborers they built the roads and canals over which the imperial army moved and the city walls and frontier fortifications that buttressed the defense of the realm. In some periods women as well as men might be called up for labor service.

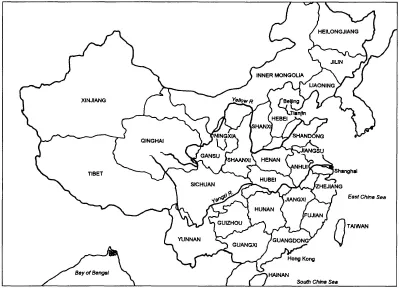

Map 1.3 China's provinces in the second half of the twentieth century. Adapted by Don Graff based upon Interpreting China's Grand Strategy, Michael D. Swaine and Ashley J. Tellis (Santa Monica, CA: Rand Corporation, 2000)

Other resources provided the materials for the instruments of war. Timber from the mountain fringes of the Sichuan basin made possible the construction of the great river flotillas that swept down the Yangzi to conquer the south in 280 and 589, and the forested hills of the Yangzi watershed and the coastal provinces of Zhejiang and Fujian provided for the huge treasure ships of Zheng He's fleet in the early Ming. Under the Northern Song dynasty, deposits of iron in Shandong, northern Jiangsu, and the Henan-Hebei border region were the basis for an arms industry that supplied China's soldiers with spearheads, arrowheads, swords, helmets, and armor for both man and horse. In the early eleventh century, foundries in these areas not far from the capital city of Kaifeng were producing 58,000 tons of iron a year, much of which went to meet the needs of the military.2

The Chinese heartland was wanting in regard to only one of the essential tools of premodern warfare. Its forested mountains and densely populated farmland were not well suited for the raising of horses, and this was especially true of the warmer and wetter lands south of the Yangzi River. Although the great majority of Chinese soldiers through the ages marched and fought on foot, cavalry forces were vital because they provided a powerful offensive element on the battlefield and they alone were capable of keeping up with highly mobile nomadic opponents. When imperial control extended over the grasslands of the steppe margin, state herds of as many as 700,000 head (as in the middle of the seventh century under the Tang dynasty) provided the basis for cavalry forces that extended the emperor's authority to even more distant regions. When control over the pastures was lost, however, the cavalry component dwindled and Chinese armies found themselves at a grave disadvantage against mounted opponents.

On the defensive, at least, investment in infrastructure made possible by China's vast human and material resources could compensate for a shortage of horses. Towns and cities were surrounded by massive walls built of stamped earth (hangtu), and the same method was used to construct the early versions of the northern frontier fortifications that became known as the Great Wall. During the Song and Ming periods, fortifications became more elaborate and walls acquired facings of stone or brick. Some of these city walls still had defensive value as late as the Civil War of 1946-1949. Since water transport was by far the most cost-effective means of moving bulky goods in premodern times, imperial governments also devoted considerable attention to augmenting and connecting China's rivers with man-made canals. The most famous of these, the Grand Canal, was first opened by the Sui dynasty at the beginning of the seventh century to connect the Lower Yangzi region with the Yellow River and the area around today's Beijing; carefully maintained by subsequent dynasties, parts of the canal remain in use today. State granaries were established at key points on the riverine transportation network, both to provide for the needs of military campaigns and to give relief to the population in the event of famine.

It was only after the Western imperialist onslaught began in the Opium War of 1839-1842 that the military resources and infrastructure characteristic of more than two thousand years of Chinese history began to see significant changes. Steam-powered vessels gave the British and other foreign interlopers easy access to China's internal waterways, which now became avenues for invasion. The climax of the Opium War came when water-borne British forces cut the Grand Canal where it meets the Yangzi at Zhenjiang, then moved upstream to attack the city of Nanjing. Foreign warships would continue to ply China's rivers until Communist field artillery denied HMS Amethyst passage of the Yangzi in 1949. By the last decades of the nineteenth century, China's most capable statesmen and military leaders were well aware that the empire would have to adopt key Western technologies in order to defend itself effectively. These included not only steamships and modern rifles and artillery, but also the railroad and the telegraph. The first Chinese steamships were built in the 1860s, but telegraphs and railroads—far more intrusive presences in the ancestral landscape—had to wait much longer. A short railway line built by foreigners near Shanghai in 1876 was purchased and dismantled by Qing authorities the following year, and it was not until after 1900 that China's first major trunk lines were built. The telegraph (and later telephone and wireless communications) allowed closer control and better coordination of armed forces, and the railway held out the hope that the country could be more effectively defended by forces operating on interior lines. The railway was a two-edged sword, however. Fears that foreign-financed and -controlled rail lines would permit foreign penetration of the Chinese hinterland contributed to the mood of crisis that preceded the Wuchang Uprising of 1911, which precipitated the fall of the Qing dynasty. The nation's rail network did indeed facilitate the Japanese invasion and occupation of eastern China in 1937-1945, but at the same time the invaders found their communications, logistics, lines of advance, and zones of occupation tied to the railway lines. The new technology offered unprecedented opportunities, but also imposed its own constraints on military operations.

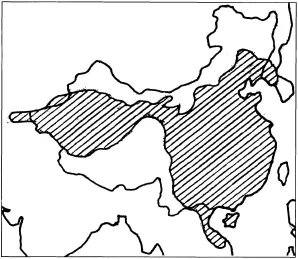

Map 1.4 A Strong dynasty: Han circa 100 B.C.E. Adapted by Don Graff based upon Interpreting China's Grand Strategy, Michael D. Swaine and Ashley J. Tellis (Santa Monica, CA: Rand Corporation, 2000) p. 42

Map 1.5 A weak dynasty: Ming circa 1640 C.E. Adapted by Don Graff based upon Interpreting China's Grand Strategy, Michael D. Swaine and Ashley J. Tellis (Santa Monica, CA: Rand Corporation, 2000) p. 42

The new prominence of steamships and railways from the late nineteenth century onward required the exploitation of new resources, most notably coal. Several areas of northern China (particularly Shanxi province) were found to hold rich reserves of coal, which remained an important fuel source even at the end of the twentieth century. As late as 1980 there were still some 10,000 steam locomotives operating in China, and diesel and electric locomotives will not likely bury the last steam engine until the second decade of the twenty-first century. Military aviation (from 1913) and motor vehicles demanded another sort of fuel. For more than two decades, China's need for oil was largely met by the great oilfield opened at Daqing in Manchuria in the early 1960s. Today, however, China no longer produces all of the petroleum needed by its rapidly growing economy, and the quest for new oil reserves is an important factor behind the assertion of sovereignty over the South China sea. Initially dependent on waterborne transit, China turned to rail transportation in the twentieth century and is only now beginning to create a modern highway system.

In spite of these changes, Chinese military logistics in the twentieth century did not represent a surgical break with the imperial past. Mao's armies in 1949 still moved in the traditional manner, by horse and foot, and many PLA units continued to rely on horse, donkey, and even camel transport long after the establishment of the People's Republic. Even without considering China's relative poverty, labor-saving devices did not always make sound sense. As the Chinese intervention in Korea in the winter of 1950-1951 showed, packing supplies in by porters who could disappear in the daytime was more effective than hauling things in train and truck convoys easily detected by the enemy's aerial reconnaisance. And the size of China's population (1.158 billion in the 1992 census and about 1.3 billion in 2001) meant that labor was always cheap relative to capital equipment. In recent years, however, China's large population has come to be regarded more as a burden than an asset. The country is no longer self-sufficient in grain, and the imposition of birth control policies reflected the fear that economic advances and improvements in the standard of living would be eaten up by population growth.

An additional resource needs to be mentioned, one that was by no means unimportant in premodern times and has become essential in today's world of high-technology warfare: educated, literate, highly skilled, and innovative personnel. Clerical personnel were a presence in Chinese armies throughout the imperial period (as evidenced, for example, by the Han-period documents of military administration recovered from Edsen-gol in Inner Mongolia), and the spread of woodblock printing during the Northern Song period must have led to an increase of popular literacy. Well-known Chinese innovations of the imperial period included not only printing, but also paper, gunpowder, and the mariner's compass. After 1500 C.E., Chinese technology began to lag behind that of the West, probably due more to revolutionary developments in Europe than stagnation in China. After the middle of the nineteenth century, however, the Chinese began to master one Western technology after another, from the steam engine and the telegraph to jet aircraft, the atomic bomb, and intercontinental ballistic missiles. The gap has not been entirely closed today, but it is clear that the West's continued technological superiority is now dependent on contin...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Maps

- Preface to the Updated Edition

- Chronology

- Editors' Note

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Continuity and Change

- 3. State Making and State Breaking

- 4. The Northern Frontier

- 5. Water Forces and Naval Operations

- 6. Military Writings

- 7. The Qing Empire

- 8. The Taiping Rebellion: A Military Assessment of Revolution and Counterrevolution

- 9. Beyond the Marble Boat: The Transformation of the Chinese Military, 1850–1911

- 10. Warlordism in Early Republican China

- 11. The National Army from Whampoa to 1949

- 12. The Sino-Japanese Conflict, 1931–1945

- 13. “Political Power Grows Out of the Barrel of a Gun”: Mao and the Red Army

- 14. Always Faithful: The PLA from 1949 to 1989

- 15. China's Foreign Conflicts Since 1949

- 16. Recent Developments in the Chinese Military

- Chinese Place Names

- About the Contributors

- Index