eBook - ePub

Contemporary Public Health

Principles, Practice, and Policy

- 310 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Contemporary Public Health

Principles, Practice, and Policy

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Contemporary Public Health by James W. Holsinger, James W. HolsingerJr.,James W. Holsinger Jr. in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Medical Education. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Social and Ecological Determinants of Health

In 2003 the landmark report Unequal Treatment drew the nation’s attention to disparities in the way health care is delivered to racial or ethnic minority groups.1 Studies had documented that patients with similar clinical presentations but different races or ethnicities received different clinical recommendations and different levels of clinical care. The report also documented disparities in access to care and health insurance coverage. The health care system responded by launching a variety of initiatives to study the issue, standardize care delivery, heighten providers’ cultural competency, and increase minority representation among health care professionals. The effort to expand access to medical care and health insurance coverage has been a central theme of health care reform.

Although these efforts have yielded some progress in reducing disparities in health care,2 disparities in health itself persist. African American infants are twice as likely as white infants to die before their first birthday, a ratio that has been nearly the same for more than forty years.3, 4 Between 1960 and 2000 the standardized mortality ratio for blacks relative to whites changed little, from 1.472 in 1960 to 1.412 in 2000, and by 2002 there were an estimated 83,750 excess deaths in the United States among blacks.4 The maternal mortality rate is also higher among some racial and ethnic minority groups.5 For example, black women were around 3.4 times as likely as white women to die of pregnancy-related causes in 2006—a difference of 32.7 versus 9.5 maternal deaths for every 100,000 live births.6

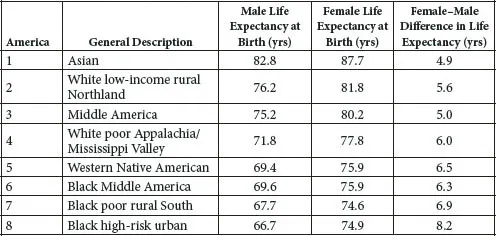

In the “Eight Americas” study, Murray and colleagues divided the U.S. population into eight groups: Asians (America 1), below-median-income whites living in the Northland (America 2), Middle Americans (America 3), poor whites living in Appalachia and the Mississippi Valley (America 4), Native Americans living on reservations in the West (America 5), black Middle Americans (America 6), poor blacks living in the rural South (America 7), and blacks living in high-risk urban environments (America 8).7 For males, the difference in life expectancy between America 1 and America 8 was 16.1 years (table 1.1), as large as the gap between Iceland, which had the highest male life expectancy in the world, and Bangladesh.7

Table 1.1. Life Expectancy of Eight Demographic Subgroups in the United States

Source: Murray CJ, Kulkarni S, Ezzati M. Eight Americas: New perspectives on U.S. health disparities. Am J Prev Med. 2005;29(5 Suppl 1):4–10.

Health disparities are just as large in some cities of the United States. For example, in Orleans Parish (New Orleans), life expectancy varies by 25.5 years between zip codes. In zip code 70112—the neighborhoods of Tulane, Gravier, Iberville, Treme, and the central business district of New Orleans—life expectancy is 54.5 years,8 comparable to the 2009 life expectancy reported by Congo (55 years), Nigeria (54 years), and Uganda (52 years).9

Health disparities related to race and ethnicity persist even among patients in health care systems that offer similar levels of access to care and coverage benefits, such as the Veterans Health Administration and Kaiser Permanente integrated health care systems.10, 11 This evidence tells us that the causes of and solutions to such disparities lie beyond health care.

Determinants of Health and Health Disparities

Understanding the causes of health disparities requires an understanding of the determinants of health itself. Morbidity and mortality are influenced by intrinsic biological factors such as age, sex, and genetic characteristics. Some other risk factors that affect health are referred to as “downstream” determinants because they are often shaped by “upstream” societal conditions. For example, medical care is important, particularly when people become ill, but other factors influence whether people become ill and their resilience and response to treatment. Personal behaviors and actions—such as tobacco use, seeking medical care for chest pain or other health complaints, and adherence to providers’ recommendations—also affect health outcomes. Fully 38 percent of all deaths in the United States have been attributed to four health behaviors: tobacco use, diet, physical activity, and problem drinking.12 Some health problems are produced directly through environmental exposures to physical risks, such as respiratory illness induced by air and water pollution, foodborne infections, injuries sustained in motor vehicle crashes, and the physical and mental trauma resulting from crime.13, 14

However, exposure to these immediate, or proximate, health risks is itself shaped by the context or conditions in which people live—the distal or “upstream” determinants of health.15–22 Living conditions influence the degree to which people are exposed to environmental risks, can pursue healthy behaviors, or are able to obtain quality medical care.23–26 What are known as social determinants of health—personal resources such as education and income and the social environment in which people live, work, study, and play—influence whether people become ill and the severity of illness.27 They affect access to health care but also patients’ vulnerability to illness and their ability to care for conditions at home. Social determinants provide an important key to understanding health disparities in the United States and, as this chapter explains, are themselves the product of more upstream societal influences.

The Interaction of Education and Income

The relationship between affluence and health has been described throughout history. In modern times, the Whitehall studies from the 1970s in the United Kingdom and decades of subsequent research throughout the world have documented large health inequities associated with social class and occupation.28 The most familiar social determinants in the United States are income and education. Adults living in poverty are more than five times as likely to report only fair or poor health compared with adults whose incomes are at least four times the poverty level.29 In adults, serious psychological distress is more than five times as common among the poor.3 Men and women in the highest income group can expect to live at least 6.5 years longer than poor men and women.20

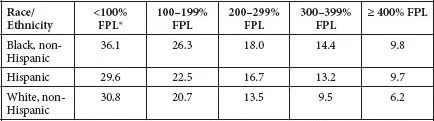

The relationship between income and health is not restricted to the poor. Studies of Americans at all income levels reveal inferior health status in lower versus higher income strata (table 1.2).20 For example, the life expectancy of a 25-year-old with a family income that is 400 percent or more of the poverty level (more than $87,000 per year for a family of four in 2009) is 55.7 years, with progressively shorter life expectancies as family income declines: 53.8 years with an income 200 to 399 percent of the poverty level, 51.4 years with an income 100 to 199 percent of the poverty level, and 49.2 years with an income less than 100 percent of the poverty level. The same health gradient by income is apparent in the prevalence rates for coronary heart disease, diabetes, and activity limitations due to chronic disease. Even those with incomes at 300 to 399 percent of the poverty level have worse health outcomes than those with incomes of 400 percent or greater.20

Table 1.2. Self-Reported Health by Income, Race, and Ethnicity

Note: Values refer to the proportion of adults aged 25 years and older who described their health as “fair” or “poor.”

Source: Braveman P, Egerter S. Overcoming Obstacles to Health. Princeton, NJ: Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; 2008.

*FPL, federal poverty level.

Source: Braveman P, Egerter S. Overcoming Obstacles to Health. Princeton, NJ: Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; 2008.

*FPL, federal poverty level.

This pattern is of great importance to the large and growing middle-class population of the United States. A common misconception among the public and policy makers is that health outcomes are compromised only for those few members of the population living at the extremes of social disadvantage. The mistaken belief is that only those living in extreme poverty or in oppressed urban neighborhoods, in rural areas, or on Native American reservations are confronted by living conditions of sufficient severity to affect health. Yet the scientific evidence documents a clear income gradient and dose-response relationship between income or wealth and health, suggesting that all members of the population, including the middle class, experience inferior health outcomes compared with more affluent members. Current economic trends are expanding the size of the middle class in the United States (see later), and the adverse health risks they experience carry increased public health implications.

That income is important to health may not be surprising to some, but the magnitude of the relationship is not always recognized. For example, Krieger and colleagues reported that 14 percent of premature deaths among whites and 30 percent of premature deaths among blacks between 1960 and 2002 would not have occurred if all persons had experienced the mortality rates of whites in the highest income quintile.30 Woolf and associates reported that 25 percent of all deaths in Virginia between 1996 and 2002 would have been averted if the mortality rates of the five most affluent counties and cities existed statewide.31 Muennig and colleagues estimated that living at less than 200 percent of the federal poverty level claimed more than 400 million quality-adjusted life years between 1997 and 2002, a larger effect than tobacco use and obesity.32 These estimates all rely on assumptions about causality that ignore the influence of confounding variables, but they suggest that the confluence of conditions existing among people with limited income exerts a much greater health influence than is widely appreciated.

An important pathway to income is education, and the literature documents profound health disparities among adults with different levels of educational attainment. Adults who lack a high school education or...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Dedication

- Foreword

- Preface

- Introduction: History and Context of Public Health Care

- 1. The Social and Ecological Determinants of Health

- 2. The Health of Marginalized Populations

- 3. Public Health Workforce and Education in the United States

- 4. The Role of Community-Oriented Primary Care in Improving Health Care

- 5. Who Is the Public in Public Health?

- 6. Public Health Services and Systems Research: Building the Science of Public Health Practice

- 7. National Accreditation of Public Health Departments

- 8. Contemporary Issues in Scientific Communication and Public Health Education

- 9. Partnerships in Public Health: Working Together for a Mutual Benefit

- 10. The Organizational Landscape of the American Public Health System

- 11. International Lessons for the United States on Health, Health Care, and Health Policy

- Conclusion: Future of Public Health

- List of Contributors

- Index