![]()

Part One

From Lawlessness to the Rule of Law

![]()

1

Chinese Media and the Rule of Law

The Case of the China Youth Daily, 1979–2006

Qiang Fang

Since the early days of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), CCP leaders such as Mao Zedong have repeatedly stressed the importance of public media to serve the people. According to Julian Chang, Mao first perceived the importance of political propaganda in the 1920s.1 In 1942 Mao evidently stated that literature and art should serve only four kinds of people: workers, farmers, soldiers, and the urban petite bourgeoisie.2 One year before the CCP took over China, Mao further addressed the role of newspapers, which would “allow the Party’s principles, guidelines, policies, working goals, and methods to be spread to the masses in the quickest and broadest way.” Because of the importance of newspapers, Mao also said that it was crucial for the Party to make them appealing to the masses and to correctly publicize the principles and policies of the Party.3 In 1957, with Mao’s encouragement, major intellectual newspapers began lambasting the wrongs of the Party. But as some criticisms went beyond the tolerance of the leaders, Mao and his adherents launched the Anti-Rightist Movement. They accused the editors of those newspapers of being reactionaries and rightists and believed that they stood against the masses.4 During the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976) public media remained a pivotal tool of the CCP and, as Merle Goldman and Lowell Dittmer have argued, were even used as a weapon in political warfare.5

Shortly after the end of the Cultural Revolution, however, a reform occurred in public media that became a part of China’s open policy. Indeed, the recent reform of the media is not the first one in the history of the CCP. According to Leonard L. Chu, three media reforms were conducted in the 1940s and the 1950s.6 Yet, in terms of width and depth, the latest reform dwarfs all previous ones. Because of its significance, scholars around the world have spilled much ink over the post-1976 media reform in China.

Some scholars study the Chinese public media as a whole, while others center their attention on specific and individual media in this period.7 Despite different approaches, most scholars tend to agree that this reform and consumerism have brought certain freedoms to China’s press.8 After the 1989 crackdown on the democratic movement, however, the Chinese government briefly tightened its control over the media.9 After Deng Xiaoping made his “southern tour” to support further reform in 1992, and especially after the CCP terminated its subsidy to the government media, Chinese public media have undergone even more profound reform.10 For the question of whether the media reform has weakened or strengthened the CCP’s control over propaganda, however, there has been a disagreement between two schools of scholars. Researchers such as Daniel Lynch, James F. Schotton, William A. Hachten, Leonard Chu, and Paul Siu-nam Lee argue that the media reform has resulted in the receding of CCP’s ability to mold people’s values and beliefs,11 whereas scholars such as Zhongdang Pan, Ashley Esarey, Marie Brady, and David Shambaugh contend that the reform has actually buttressed the Party’s control over propaganda.12 Both schools, as Guoguang Wu comments, have “certainly contained partial truth” and have enriched our understanding of the development of the Chinese public media in this period.13

In this chapter I shall not try to deal with this question directly. Instead, I shall examine one area that most scholars of Chinese public media have yet to explore: the role of Chinese newspapers in the CCP’s repeated promises of the rule of law.14 To better fill that gap, I shall study the China Youth Daily (Zhongguo qingnianbao; hereinafter CYD), a national newspaper that is both influential and representative. The reasons for choosing it are numerous. First, the CYD is run by the Chinese Communist Party Youth League, making the paper’s importance second only to that of the CCP’s primary mouthpiece, the People’s Daily. Second, the CYD is one of the most popular newspapers in China.15 Third, because most readers of the CYD are young people, who constitute the biggest proportion of the criminals, the legal reports of the newspaper are very important. Fourth, as we will see, the CYD has since the mid-1980s devoted much energy and space to covering law-related reports that help promote the CCP’s efforts to construct a rule-of-law China. More important, the CYD has always been regarded as one of the boldest national dailies, owing to its harsh criticisms and exposure of lawbreaking officials.16

The Cultural Revolution. (University of Michigan)

Some questions to be asked in this research are: What kind of role did the CYD play in tandem with the CCP in promoting the CCP’s goal toward the rule of law? When did the CYD begin to focus on legal issues? What steps did the CYD take to promote the rule of law in China? How and why did the newspaper adapt to the ever-changing political and legal situations in this period? Was the newspaper merely a propaganda tool of the Party? How did the CYD balance its reports to serve both the Party and the general readers? To what extent did the CYD help promote the cause of the rule of law in a reformed China? What are the limitations of the CYD?

To answer those questions, I shall first entertain the CCP’s call for the rule of law17 in the aftermath of the Cultural Revolution. Then I shall analyze the three major shifts of the strategies of the CYD from 1979 to 2006. Finally, I shall examine the historical role of the CYD in the course of China’s march to the rule of law as well as its limitations.

CCP’S ENGAGEMENT WITH THE RULE OF LAW

Shortly after the tumultuous Cultural Revolution officially ended in 1976, the new leaders, including Deng Xiaoping, who had been attacked during the Cultural Revolution, called for legal reform. At the Third Plenary Session of the CCP held in late 1978, Ye Jianying, the president of the National People’s Congress (NPC), claimed that since the establishment of the PRC, China had never had a decent legal system, which was the main reason that the Gang of Four was able to destroy the socialist legal system and cause numerous deaths. Therefore, Ye noted that “all nations should have a legal system that must have stability, continuity, and immense authority.”18 In 1979 Deng Xiaoping admitted that China had too few laws and asserted that China should have hundreds of new laws. “Neither democracy nor legal system,” Deng continued, “should be loosely grasped.”19

Indeed, legal reform marked a momentous period in China’s lawmaking after 1978.20 China’s new leaders restored the procuratorate in 1978, which had been terminated in 1975, and the Ministry of Judiciary in 1979. Also in 1979 both Beijing and Shanghai allowed the reestablishment of the Lawyer Association. In 1979 and 1986 the NPC passed the Criminal Law and the Civil Law. The most important law enacted in the 1980s was the 1982 constitution, which stated that no person or organization “has the privilege of surpassing the constitution and law.”21

In the 1990s, especially after the Fourteenth Plenary of the CCP in 1992 proposed the establishment of the socialist market economy and Jiang Zemin’s call for making China a state governed by the rule of law in 1996,22 legal reform drastically sped up its pace. A key rationale underscoring the rule-of-law effort was that leaders such as Jiang and some scholars believed that the market economy should be a rule-of-law economy.23 Consequently, both the NPC and local congresses enacted thousands of laws. In the NPC alone, more than two hundred laws were established between 1989 and 2002, almost three times as many as were enacted in the 1980s. Many important laws such as the Judge Law, the Procurator Law, and the Criminal Procedure Law were promulgated in the 1990s. As Stanley B. Lubman aptly notes, “Virtually every element of Chinese law today was either revived or newly created in the course of two decades of extraordinary economic and social change.”24

As the mouthpiece of the CCP, public media have played a significant role in fostering the rule of law in this period. Being one of the most renowned and influential newspapers in the nation, the CYD undoubtedly played a role that was commensurate with its political and social status. To examine the role of the CYD in China’s construction of the rule of law, I have collected and recorded almost all law-related reports published by the CYD between 1979 and 2006. During those twenty-eight years, there were a remarkable number of reports: about 13,670.25 All the law-related reports can roughly be classified in the following five categories,

- Propaganda: CYD carried out the principles of the CCP’s leaders and the central government by publishing leaders’ speeches and governmental orders on law, laws newly passed by the NPC, and crucial editorials from the People’s Daily.

- Problems of law enforcement: CYD published stories about cases involving problems of the courts, judges, police, and other law enforcement agencies.

- Crusader and protector: CYD acted as a crusader against official violations of people’s legal rights and a protector of aggrieved persons.

- Comments, letters, and debates: CYD published commentary and letters written mostly by its reporters and legal specialists regarding the nature and internal problems of the modern-day legal system. Debates on certain legal issues were printed.

- Educator and deterrent: Partly to follow CCP leaders’ calls for constructing the rule of law, and partly to help instill legal sense and knowledge in the populace, the CYD served as both an educator and a transmitter of legal knowledge by telling readers what was illegal and what was legal through specific reports or cases. In addition, reports of the punishments imposed on the culprits functioned as a deterrent to potential criminals.

If we simply read a year’s worth of CYD reports with these five categories in mind, we may not find any significant pattern. But after I examined the CYD reports for twenty-eight years, three distinct periods, each of which contains different clear emphases, emerged: Propaganda and Elementary Educator (1979–1985), Propaganda and Professional Educator (1986–1998), Critic and Advocator of the Rule of Law (1999–2006).

PROPAGANDA AND ELEMENTARY EDUCATOR (1979–1985)

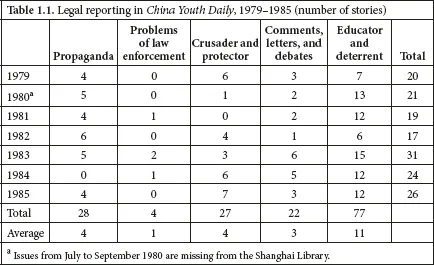

Although legal reform was ignited by the CCP in the late 1970s, it seems that the wave of reform did not reach the public media immediately. During the seven years from 1979 to 1985, there was only minuscule coverage of law-related news or cases in the CYD. As Table 1.1 shows, reports in the CYD corresponding to the five aforementioned categories averaged about twenty-two per year. Most of the reports, seventy-seven, came from the fifth category, educator and deterrent.

In this short period the CYD published a total of twenty-eight reports that fell into the category of Propaganda. On July 5, 1979, an editorial ran in the newspaper titled “Studying Law, Following Law, and Protecting Law,” which conspicuously reflected the tone and principles of the Party. “The seven laws passed by the second meeting of the Fifth National People’s Congress are a big issue in our people’s life,” the editorial said. “It is important to enhance the socialist democracy and perfect the socialist legal system.” In particular, the editorial admonished youth that it is an honor to abide by law and a shame to violate it. Yet the editorial seemed unclear about the true meaning of the rule of law, because it further claimed that following the law was tantamount to following the Party.26 In that sense, the Party is law and vice versa. This is a distortion of the principle of the rule of law, which essentially means that no one is above the law and the law must be applied equally.27

Table 1.1. Legal reporting in China Youth Daily, 1979–1985 (number of stories)

As a tool of the Party, the CYD also published laws that had been passed or promulgated by the NPC or the State Council.28 For instance, right after the new 1982 constitution was passed by the NPC, the CYD published the complete text.2...