- 444 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

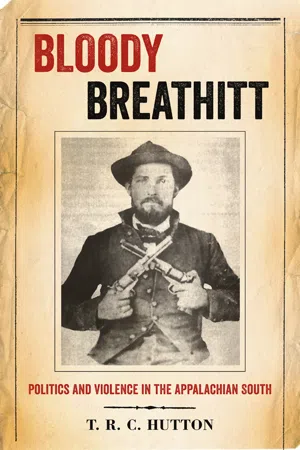

Yes, you can access Bloody Breathitt by T.R.C. Hutton in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

The University Press of KentuckyYear

2013Print ISBN

9780813161242, 9780813136462eBook ISBN

97808131424251

“TO THEM, IT WAS NO-MAN’S LAND”

Before Breathitt Was Bloody

Without hazarding any thing, I think, Sir, I may say, more of the happiness of this Commonwealth, depends upon the County Government under which we live, than upon the State or the United States’ Government.

—Alexander Campbell, delegate to Virginia’s

Second Constitutional Convention (1829)

Second Constitutional Convention (1829)

As an old man, George Washington Noble recalled watching a “pitched battle” when he was a child in Breathitt County, Kentucky, in the 1850s. It was a semiofficial Court Day event, a hand-to-hand tussle for money and prestige between various communities’ “champion fighters,” referred to locally as “Tessy Boys.”1 As in a duel, the fights employed seconds to prevent foul play and to give a potential deadly free-for-all a measure of ritualized order; it was, after all, around the same time that another fight with no public supervision had ended in a fatal stabbing.2 In Jackson, Breathitt’s county seat, this display of fisticuffs added entertainment, and an aura of masculine brio, to a staid political and legal event, augmenting the more formal proceedings going on inside the courthouse. It was an inclusive activity, establishing democratic homosocial interactions between men from disparate neighborhoods across a very large county, gathering “high and low into deeply charged, face-to-face, ritualized encounters.”3 A rough, unruly, violent spectacle occurring during a public event that ensured civic order, the Tessy Boys’ fight serves as an allegory for Breathitt County’s social and political existence in the two decades before the Civil War. The incorporation of fighting into a state-ordained ritual like Court Day (an always-boisterous event in the antebellum South) mirrored the state’s marginally successful attempt to bring stability to a chaotic environment.4

Antebellum Breathitt County was just another representation of southern society re-created in the Kentucky mountains. The Tessy Boys may have had a peculiar local name, but they were a pretty close facsimile to the semiorganized Court Day tussles that were then de rigueur throughout Kentucky and the other slave states.5 Reading about Bloody Breathitt in 1905, one would have been falsely led to believe that it had always been a wooded preserve for antediluvian chaos. Once it had been named “Bloody Breathitt” in the 1870s this relatively peaceful stage of its history, Tessy Boys and all, was mostly forgotten.

Long before the homicides and mayhem for which it would later be known, antebellum Breathitt County did contain the potential for turmoil. The 1839 formation of Breathitt County in eastern Kentucky’s Three Forks region (the drainage area of the Kentucky River’s three tributaries) happened out of desire to bring a governmental and commercial order to an inert, untapped wilderness.6 Well to the east of the old Wilderness Road (the main road between Virginia and central Kentucky that provided access to both for portions of southeastern Kentucky’s mountains), it was one of the last areas of Kentucky with a permanent population. Breathitt County’s creation was brought about by landowners who saw the area as a commodity rather than just a living space. It was a governmental entity, like other counties, but it was also a business venture carried out for personal, not public, gain. Moreover, it was a venture that ran counter to the interests of many of the preexistent population. This was meant to be a profitable order and, like many other such schemes of the nineteenth century, it had unforeseen outcomes.

“These people lived here in seclusion for several years; not knowing [of ]what country or nation they were citizens”

The story of early Breathitt County is one of in-state sectionalism, an upland county founded according to mostly lowland interests. The enormously luxuriant rolling hills of the Bluegrass in north-central Kentucky, a cultivator’s paradise where a facsimile of the Virginia plantation economy could be re-created, was the first section of any economic consequence for white settlers and their slaves.7 “The [non-Indian] population of Kentucky until the separation from Virginia,” wrote one early twentieth-century Kentucky historian, “was practically confined to the Bluegrass.”8 From there Kentuckians spread outward after 1792 statehood, south to the Green River Valley and westward to the tobacco-growing Pennyroyal and Jackson Purchase sections.

The Cumberland Plateau, the mountain range that covers most of eastern Kentucky, was always defined in contradistinction to the rest of the state, and it was a subject of little curiosity in the early Republic. In 1751 explorer Christopher Gist and his party probably became the first white men to see Breathitt County’s future location when they passed through on their return from the Ohio Country.9 “None of any particular note” is the only comment given for Kentucky’s mountains in one 1815 atlas.10 With the exception of longhunters and trappers, most first-generation Kentuckians considered the plateau little more than an impediment.11 Settlers arrived only after lower-lying areas like the Bluegrass had become surveyed, taxed, and overcrowded beyond their satisfaction. Recognizing that theirs was a relatively new community, Kentucky mountaineers of the Civil War era still called the Bluegrass their state’s “old settlements.”12

In 1889 New England writer Charles Dudley Warner described Kentucky as divided into three distinct regions, “like Gaul,” an oft-repeated allusion to Caesar’s Commentaries on the Gallic War.13 The dramatic contrast between the highlands and the central Bluegrass (the western third was eventually overshadowed or conflated with the central Bluegrass) popularized a more simplistic geographical commentary asserting “two Kentuckys” in place of Warner’s three: one defined by the Bluegrass’s agrarian wealth and the other by the highlands’ hardscrabble deprivation.14 This geographic metaphor came to influence Kentuckians’ self-image. The patrician, commercially vigorous Bluegrass was obliged to share Kentucky’s (inter)national image with the plebian, underdeveloped uplands, “polished blue grass civilization” eternally saddled with “the semi-barbarism of the mountains.”15 Residents of both sections eventually took this exaggerated stark contrast to heart. Breathitt County native E. L. Noble (George Noble’s much younger cousin) portrayed his ancestors entering stateless “forest primeval worlds, rich in primeval glory and wealth of worlds now unknown to man. . . . These people lived here in seclusion for several years; not knowing [of] what country or nation they were citizens.”16

Early travelers’ accounts suggest that this was an old assumption, and one quickly challenged. In 1834 New Yorker Charles Fenno Hoffman was surprised to find highland Kentuckians “sing[ing] the praises of ‘old Kain-tuck’ with as much fervor as the yeoman who rides over his thousand fat acres in the finest regions of Kentucky [that is, the Bluegrass]” despite their general “ignorance of the world.”17 Hoffman probably did not realize that his rustic hosts were likely themselves recent arrivals. Moreover, as unaware as eastern Kentuckians may have been of the “world” (which, to Knickerbocker Hoffman, was probably restricted to east of the Hudson River), they knew quite well who certified their contracts, counted their votes, and accepted their tax money. Early nineteenth-century eastern Kentucky was sparsely populated, but it was not the wilderness primeval “beyond the polis,” as it was often portrayed.18 As Durwood Dunn noted about Cades Cove, Tennessee, during the same period, “isolation was always relative.”19

Isolation was relative, and also a problem partially solved by bringing government closer to home. For generations, Kentuckians who chose to settle in the mountains were forced to make a long trip westward to see or use any functions of government. Early state maps show tremendous counties covering vast amounts of land stretching far from their respective Bluegrass courthouse towns. In the Three Forks region extraordinary circumstances made it abundantly clear that a more available jurisprudence system was necessary. In 1805 conflict arose among cattlemen living between the middle and north forks. Steers belonging to the Strong and Callahan families strayed from a Virginia-bound cattle drive and destroyed crops belonging to one John Amis. Amis took revenge on his careless neighbors by somehow drowning a number of their cattle in the north fork. In retaliation, the Strongs and Callahans allegedly killed Amis’s own livestock and assaulted his wife. Amis and his confederates struck back days later by firing on the offending party and shots were returned, with no immediate resolution to the fracas. The shooting eventually died down, and word reached the state capital, Frankfort, of what had gone on, but prosecution of the accused would be difficult, with Madison County’s seat of government nearly a hundred miles from the Three Forks. The Kentucky General Assembly first formed Clay County out of Madison and two other counties in 1807, a landmass with fewer than six inhabitants per square mile.20 If the state government’s intention was to bring law and order to the area, it would seem that the effort was only partially successful; Amis was fatally shot while on the witness stand at Clay County’s first court session.21

Typically, however, new mountain counties were founded because of everyday civic needs and desires. After a pioneer settlement turned into a multifamily village, those that saw a need for closer government—usually those with the most property—had only to gather a dozen or so signatures to form a new county. As tiny villages became county seats, petitioning “first families” gained tremendously, and enough of their new earnings trickled down to their neighbors to create a general agreement that county formation was an unalloyed good.22 In the spirit of pleasing voters, their requests were approved with alacrity. Drawing new county boundaries and the settling of subsequent border disputes became the Kentucky General Assembly’s primary functions during...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Introduction: “The darkest and bloodiest of all the dark and bloody feud counties”

- 1. “To them, it was no-man’s land”: Before Breathitt Was Bloody

- 2. “Suppressing the late rebellion”: Guerrilla Fighting in a Loyal State

- 3. “The war spirit was high”: Scenes from an Un-Reconstructed County

- 4. “The civilizing and Christianizing effects of material improvement and development”

- 5. Death of a Feudal Hero

- 6. “There has always been the bitterest political feeling in the county”: A Courthouse Ring in the Age of Assassination

- 7. “The feudal wars of Eastern Kentucky will no doubt be utilized in coming years by writers of fiction”: Reading and Writing Bloody Breathitt

- Epilogue

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index