![]()

1

NOSTALGIA, NARRATIVE, AND NORTHERN CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT HISTORY

What was that place called Brooklyn really like back then, when you were growing up?

—Elliot Willensky, When Brooklyn Was the World,

1920–1957

Only two things have remained constant in the history of race in Brooklyn: the social symbolism of color and the extraordinary maldistribution of power. The former has faithfully followed the career of the latter.

—Craig Steven Wilder, A Covenant with Color:

Race and Social Power in Brooklyn

On February 3, 1964, one of the largest civil rights demonstrations in U.S. history occurred. Nearly half a million students boycotted a racially segregated municipal public school system as parents and activists demanded a plan for comprehensive desegregation. Ten years after the Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education decision had declared racially segregated public schools unconstitutional, this city’s government had failed to desegregate the school system. The integration movement rallied behind a Christian minister, a man known for his eloquent, trenchant sermons against racial discrimination and poverty. He transformed his church into a movement headquarters, which organized racially integrated “freedom schools” throughout the city. The man and the movement made history.

But this minister’s name was Milton, not Martin; and his church was in Brooklyn, New York, not Birmingham, Alabama.1

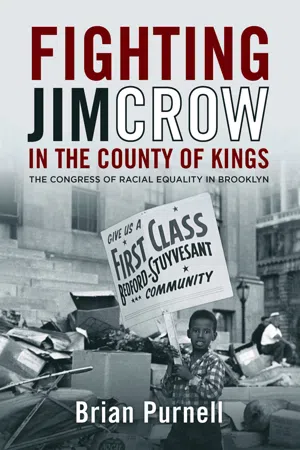

Fighting Jim Crow in the County of Kings narrates the history of the early 1960s civil rights movement in Brooklyn, New York, through an analysis of the Brooklyn chapter of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE). This book highlights the ways northern civil rights activists worked diligently for roughly five years to make forms of racial discrimination in New York City visible to the public and matters of political debate. The chapters that follow also examine how Brooklyn CORE developed a culture of interracial camaraderie through creative direct-action protest campaigns, and how it formed alliances with numerous community-based organizations and local civil rights activists, such as the Reverend Milton Galamison, referred to above. The demonstrations that clearly dramatized the everyday ways racial discrimination circumscribed black citizens’ social lives and economic opportunities won Brooklyn CORE a seat at negotiation tables, and in some cases the chapter secured jobs, housing, and improved city services for black Brooklynites. Mostly, though, an assortment of power brokers—union leaders, elected officials, real estate tycoons, business managers, and school board officials—ignored Brooklyn CORE’s protests, made limited concessions on certain demands, or used investigations and empty promises to delay dealing with widespread forms of racial discrimination. This book therefore pays close attention to Brooklyn CORE’s shortcomings and failures. Its narrative invites readers to question how any band of activists could eliminate systematic forms of racial discrimination, especially without strong, clear, consistent government support, at both the local and national levels.

Most readers will come to this book familiar with what the civil rights movement veteran Julian Bond calls the “master” narrative of the movement. This version of the civil rights movement’s history covers the mid-1950s through mid-1960s, when national leaders and nonviolent activists eradicated Jim Crow policies in the South. The movement achieved major legislative victories in the form of the Civil Rights and Voting Rights Acts and moved the country closer to true democracy, but it declined when activists brought nonviolent protest tactics north. There the civil rights movement encountered riotous African Americans, black power activists, and white backlash. This master narrative is essentially built on a series of dichotomies: North versus South; racial integration versus black power; nonviolent pacifism versus self-defense and violence; the “good early 1960s” versus the “bad late 1960s.” Like many heroic histories, the civil rights movement’s master narrative and its accompanying dichotomies overlook a far more complex, wide-ranging story. They limit civil rights movement history to roughly one decade of events that took place almost entirely in the South and in Washington, D.C. The rest of the country, and events leading up to and following the 1954–65 period, become background props in what is mostly a story of the nation’s triumph over its long history of racial discrimination.2

Academic historians have developed three frameworks that challenge this master narrative’s interpretations. The “freedom North” paradigm expands the geographic scope of the civil rights movement. These studies show that activists fought against local forms of racial discrimination outside the South before, during, and after civil rights movements emerged in southern cities and towns. Northern, urban activists created struggles for black economic and social justice that demanded employment opportunities, desegregated education systems, open housing, and increased political power. This scholarship has proven that the movement did not move from the South to the North; it was already there, and in some places it predated the more familiar southern movement. The history of the civil rights movement outside the South also shows that the national struggle against racism did not end when states or Congress passed antidiscrimination laws and enshrined voting equality; nor did northern civil rights movements fall apart because black power movements emerged. Black power, in many cities outside the South, represented continuations of earlier civil rights movement struggles, albeit with different philosophies, organizations, leaders, and strategies.3

The second framework, the “long civil rights movement” paradigm, expands civil rights movement history to before 1954 and beyond 1965. This expanded chronology locates the civil rights movement’s origins in earlier periods, and it includes radical and conservative forms of activism. Black southerners fought against Jim Crow discrimination in the early twentieth century. They pushed for what the historian Tomiko Brown-Nagin has called “pragmatic civil rights”: a protest agenda that challenged racial discrimination but protected the power and influence that black business owners and political figures wielded within the racially segregated system. The long civil rights movement paradigm also includes antidiscrimination activism spearheaded by the Old Left, particularly through studies of the Congress of Industrial Organizations and its efforts to unionize African American workers, and the antiracist activism of the Communist Party, U.S.A. The long civil rights movement framework reveals a history of struggle against American racism that unfolded over several decades, not merely one, and was marked by moments of continuity and change. It seeks to reveal how the wave of national activism that flourished in the late 1950s and the 1960s was an extension of earlier phases of antiracist activism. It also extends the chronology of the civil rights movement beyond the 1960s and examines the similarities and differences between the civil rights and black power movements.4

Last, a “black power studies” paradigm challenges a dichotomous separation of civil rights movement history from black power movement history. New histories of the black power movement have rejected representations that frame it solely as a denunciation of interracial organizations and nonviolence. They also go beyond chronologies that orient the black power movement’s origins in the mid- to late 1960s and geographical frameworks that situate the black power movement only in cities outside the South. The black power movement was southern and northern, cultural, political, and economic, revolutionary and conservative, local, national, and international, feminist, and intergenerational. Postwar black power movement organizing, these studies have begun to demonstrate, took many different economic, intellectual, cultural, artistic, gendered, and political forms.5

In addition to these three paradigms, roughly three decades of revisionist work has produced numerous new vantage points from which to study civil rights movement history. In 1980 William Chafe’s Civilities and Civil Rights paved the way for local studies of the long black freedom movement that offered new interpretations of the movement’s leadership, political and economic effects, and long-term legacies. Civil rights and black power movement histories have also expanded to include histories of the post–World War II welfare rights movements. Studies of black women in the civil rights and black power movements have forced historians to analyze how competing leadership styles, social movement philosophies, and gender ideologies influenced the modern black freedom movement. Studies of memory and the civil rights movement have analyzed how, over time, modern politics has influenced which stories about the civil rights movement people have preserved. Histories of the black freedom movement in the Southwest and transnational studies have expanded even further civil rights movement history’s geographic scope. Histories of the civil rights movement in parts of the country where Asian, Mexican, and Latin American activists fought alongside, and against, blacks and whites have pushed this field beyond a strictly black-white paradigm. All these revisionist approaches have placed the civil rights movement within much broader understandings of post–World War II U.S. and even global history.6

These revisionist interpretations have important critics, who raise questions about losing sight of a national synthesis narrative in favor of countless local studies; the dangers of blurring ideological lines between civil rights and black power; and stretching the chronological and spatial boundaries of the postwar black freedom movement to the point where the period loses its historical specificity. Fighting Jim Crow in the County of Kings does not argue against or attempt to disprove legitimate criticisms of the new paradigms. Over time, new branches of historical research, and the debates they generate, will inevitably foster new syntheses of postwar U.S. history. This book contributes to that new, emerging synthesis with a narrative analysis of interracial civil rights activism in one of the largest, most iconic postwar cities.7

This book’s analysis draws from and contributes to several of the paradigms mentioned. Brooklyn CORE’s early 1960s history shows that members of the Old Left did not disappear completely from political organizing with the onset of post–World War II anti-Communist McCarthyism but instead resurfaced and contributed to local civil rights movement campaigns. Fighting Jim Crow in the County of Kings highlights the Brooklyn movement’s connection to the national movement, but at the same time it furthers the argument that the national movement was essentially a collection of many different local variations and activists. Unlike many other histories of the northern civil rights movement, this book takes up the interracial, nonviolent phase of activism as its main subject. Who those interracial activists were, how they formed a cohesive social movement culture, how they tackled racial discrimination in their city, what they achieved, where they failed, and what happened to them are the main subjects of this book.

Set in a city that had a growing Puerto Rican population, the history of Brooklyn CORE touches briefly on the ways African Americans and whites included Puerto Ricans in the early 1960s civil rights movement. Occasionally in its campaigns, Brooklyn CORE lumped together Puerto Ricans and African Americans, claiming that both groups experienced similar forms of racial discrimination. As migrants from largely agricultural societies subject to housing discrimination, underserved neighborhoods, inferior public schools, and racially segmented job markets, Puerto Ricans and African Americans shared similar social experiences in postwar New York City. But Puerto Ricans were also multiracial Spanish speakers from a Caribbean Island who carried their own diverse ideologies about race and politics. Brooklyn CORE activists may have assumed that Puerto Ricans and African Americans experienced the same racially discriminatory system in identical ways, but political coalitions between blacks and Puerto Ricans were never natural or inevitable. In fact, the history of Brooklyn CORE reveals that many times during the early 1960s interracial civil rights activists may have spoken for Puerto Ricans in ways that Puerto Ricans might not have spoken for themselves.8

Forging strong African American–Puerto Rican ties was one challenge Brooklyn CORE faced, but maintaining members’ political focus in the face of frustrating campaigns was the most significant factor that influenced Brooklyn CORE’s rise and fall. Though most early histories of the civil rights movement posit that nonviolent, interracial protest failed in the North because northern blacks turned quickly to identity politics and violence, the history of Brooklyn CORE shows that the interracial northern civil rights movement declined slowly and several years before African Americans organized around black power, because direct-action protest could not produce tangible results quickly. Local power brokers in government, labor unions, and real estate never fully embraced the civil rights movement’s agenda in such a way that reversed decades of racial discrimination in housing and employment, and activists grew disillusioned with these power brokers’ penchant for delaying comprehensive desegregation plans. Some members of Brooklyn CORE became unfocused and traded direct-action protest targeting everyday forms of racial discrimination for massive symbolic demonstrations. The World’s Fair “stall-in” demonstration in the spring of 1964 was effectively the last major campaign that Brooklyn CORE’s interracial membership initiated. It generated a massive media response, but it showed that Brooklyn CORE activists no longer influenced public discourse in such a way that forced power brokers to negotiate, as it had done in previous years. A combination of internal and external factors led to the decline of the interracial civil rights movement in Brooklyn, but none of them really stemmed from the emergence of black power or black nationalism, which became prominent two years after the interracial, nonviolent, direct-action phase of Brooklyn CORE ended.

Not until Americans are able to see how the interracial phase of the northern, urban civil rights movement developed—not as some transplanted southern social movement being tested on foreign streets, but as a social movement that grew out of northern activists’ specific needs to fight northern forms and systems of racial discrimination—will they be able to expand their notions of how the post–World War II black freedom movement unfolded on national terms, and the ways racism is truly an American dilemma, not merely a southern one.

Part of Brooklyn CORE’s raison d’être was to make the effects of racial discrimination in the New York City visible and recognizable to ordinary citizens and municipal power brokers. Many post–World War II New Yorkers simply ignored local forms of racial discrimination. They differentiated the supposedly benign forms of segregation in their city from the pernicious racism in the South. New York State had passed the nation’s first law banning racial discrimination in employment in 1945. And no public signs designated some spaces in Brooklyn “Whites Only” and others “Colored Only.” New Yorkers, therefore, used the term de facto to describe their racially segregated social and economic worlds. De facto implied that racially segregated neighborhoods and employment patterns resulted from chance, or they reflected natural choices. Either way, de facto differentiated the North’s forms of racial difference from the South’s de jure system of racial segregation, which was enforced by law. But this distinction was only superficially accurate: the absence of racist laws in the North was never tantamount to the absence of racism. The term de facto provided convenient cover for northerners’ racial prejudices and for discriminatory policies that shaped the North. It allowed northerners to believe that, with respect to residential segregation and employment discrimination, they were not as bad as southerners, and that whatever racism existed in the North was simply unfortunate, but nonetheless uncontrollable. Or, as the novelist and essayist James Baldwin summarized, labeling New York City’s segregation system de facto meant that “Negroes are segregated but nobody did it.”9

As James Wolfinger and Jeanne Theoharis have argued, activists in northern cities struggled to address local forms of racial discrimination because “at times it hid in plain sight.” Gunnar Myrdal put it this way when he surveyed American racism in the 1940s: “It is convenient for Northerners’ good conscious to forget about the Negro.” In the North, Myrdal concluded, a social paradox existed in which “almost everybody is against discrimination in general but, at the same time, almost everybody p...