- 496 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Publisher

The University Press of KentuckyYear

2013Print ISBN

9780813190686, 9780813122335eBook ISBN

97808131433091

WHY RULERS RULE

At first sight Yeroen’s supremacy seemed to rest on unparalleled physical strength. Yeroen’s bulk and his self-assured manners gave rise to the naive assumption that a chimpanzee community is governed by the law of the strongest. Yeroen looked much stronger than the second adult male, Luit. This false impression was created by the fact that in the years of his supremacy Yeroen’s hair was constantly slightly on end—even when he wasn’t actively displaying—and he walked in an exaggeratedly slow and heavy manner. This habit of making the body look deceptively large and heavy is characteristic of the alpha male, as we saw again later when the other individuals filled this role. The fact of being in a position of power makes a male physically impressive, hence the assumption that he occupies the position that fits his appearance.

Why do people want to rule? You may think the reason is obvious—power, privilege, and perks—but it’s not. Nor does it have anything to do with the more high-minded motives of patriotism, duty, and service. What I hope to show is that all of the usual reasons aspiring rulers give for seeking high office are simply rationalizations by them to do what they are socially and biologically driven to do. Just as the orgastic pleasures associated with sex ensure procreation and contribute to the preservation of the species—regardless of the reasons people give for copulating, such as doing it for love, intimacy, or fun—the rewards that come with ultimate power likewise serve as powerful motivators for would-be rulers to do Nature’s bidding.

WHAT NEEDS TO BE EXPLAINED

During the course of my investigation into the lives and careers of 1,941 twentieth-century rulers, I uncovered a number of puzzling findings. Certain of these findings seemed obvious, but few people had bothered before to ask what they might mean. Other findings seemed contradictory. Yet other findings were so startling that I found it hard to believe they had not been reported before. Any adequate theory about the nature of ruling needs to explain all of these findings. No theory to date does.

Here is what needs to be explained.

• All nations have rulers.1 This fact is almost a truism. It is simply the way things are. Yet people should not take it for granted, since it is a remarkable happening. It represents a clear statement about the way societies work. Despite times of anarchy and the attempts of collective forms of government, such as troikas, juntas, councils, or assemblies, to diffuse executive power, one person usually emerges sooner or later to take charge of the country. Whether countries happen to be democracies or dictatorships, the people eventually want one person at the helm whom they can identify as their leader.

• Essentially all the rulers of all the nations in the world during the past century have been men. Despite the advances made by women during the last part of this past century, especially in democratic nations, males still dominate the global political scene. Even more telling, no woman rules as a dictator or wields absolute power. If a wily and persistent Eve could have tempted a rather dull-witted Adam to defy the Lord’s instructions and eat the forbidden fruit, then surely more clever and resourceful women throughout the ages should have been able to circumvent male hegemony in society at large and displace them as rulers, despite being handicapped by the burden of child-bearing, a relative lack of strength, and the oppressive efforts of men to keep them in their place.

• In many societies throughout the world, male rulers have a decided breeding advantage over other men, not only in their access to women but also in the size of the harems and the number of mistresses they keep. Among the different kinds of rulers, a relationship seems to exist between the relative amount of authority they hold and the extent of their sexual promiscuity, which, in turn, has a direct bearing on the size of their brood. Monarchs and tyrants, for instance, who seem to look upon the fertilization of nubile women as one of their sacred duties, are much more fecund than leaders of emerging and established democracies, who exercise less power.

• No identifiable form of intelligence, talent, genius, or even experience seems necessary for ruling a country. Would-be rulers do not have to pass qualifying examinations in leadership or demonstrate competence in administration or show skill in diplomacy. They do not need to have good communication skills or even be popular with their subjects. While many leaders are imaginative, worldly, and intelligent, others are pedestrian, narrow-minded, and ignorant, which suggests that demonstrated ability or achievement has little to do with securing the highest office in the land.

• Leaders need not be sane, rational, or even mentally competent to rule a country. My results reveal high rates of alcoholism, drug use, depression, mania, and paranoia among certain kinds of rulers. Remarkably, over this past century, many rulers even have managed to keep power despite being floridly crazy or demented.

• Although intellectual or academic credentials seem irrelevant for ruling, one of the time-honored ways individuals establish their qualifications for leadership is by showing physical prowess and courage in battle. If a David can slay a Goliath, then he is worthy of being crowned a king. Being a fierce “warrior” is important for being a hero, and being a hero is important for being a ruler. Therefore, it is not surprising to find that in many regions of the world a military career is a prerequisite for becoming a ruler and, in those regions where it is not, being a lawyer, who uses words as weapons, is a popular profession.

• Many leaders who come to power forcibly do not seem to learn from the mistakes of past rulers. Nor are most really interested in consulting with their predecessors and potentially benefitting from their advice. This suggests there is something about ruling or the people who become rulers that fosters a kind of personal grandiosity that blinds them to political reality and lets them believe they will be able to accomplish in the future what ex-rulers were unable to do in the past.

• In many instances, would-be rulers risk their lives to gain ultimate power and, once they have it, risk their lives to keep it. Sometimes they cling to power so tenaciously that they even ignore warnings about their imminent death. These are not occasional happenings. As my results reveal, the mortality rate among all rulers worldwide due to assassination, execution, and suicide is astounding, making ruling the most dangerous professional activity known.

• Throughout history, rulers who attain legendary status often tend to be those who have conquered other nations, won major wars, expanded their country’s boundaries, founded new nations, forcibly transformed their societies, and imposed their own beliefs on their subjects. In short, they have killed, plundered, oppressed, and destroyed. Rarely do rulers achieve greatness who have been ambassadors for peace, kept the status quo, defended free speech, promoted independent thinking, and avoided wars at all costs.

HUMANS ARE ANIMALS, TOO

While it is possible to come up with sociological, religious, or psychological theories for all of these observations, no credible explanation of ruling can ignore the potential influences of biology—although almost all past and current theories about leadership do! Missing from all explanations of political behavior to date is the simple fact that humans are mammals who belong to the order of primates, the family of hominids, the genus of homo, and the species of sapiens. As primates, they share the characteristics of other higher primates and so can be expected to act at times like monkeys and apes. Once you accept this reality, everything else about the process of becoming and being a ruler begins to make sense.

By comparing the behaviors of individuals with those of their simian ancestors, I am not trying to disparage the political activity of humans—nor, for that matter, of other primates. I am only saying there is a dimension of ruling that has not yet been adequately explored. People may choose to ignore their animal heritage by interpreting their behavior as divinely inspired, socially purposeful, or even self-serving, all of which they attribute to being human; but they masticate, defecate, masturbate, fornicate, and procreate much as chimps and other apes do, so they should have little cause to get upset if they learn that they act like other primates when they politically agitate, debate, abdicate, placate, and administrate, too.

As it happens, of all the fields of human endeavor, politics seems to be the one most rooted in primitive primate behavior. The natural and social sciences rely heavily on information-gathering, problem-solving, and reasoning. The arts rely heavily on creative expression, intuition, and the exercise of special skills. In contrast to the arts and sciences, which require the use of mankind’s highest mental faculties, located largely in the neocortex, the most evolutionarily advanced part of the brain, the striving for political power seems fueled more by secretions from man’s nether parts—his gonads and adrenal glands—as well as activity from within the limbic system and hypothalamus, the most ancient parts of the brain, all of which deal with such instinctive responses as fight-or-flight, territoriality, aggression, sex, and survival.

By saying that potential neurophysiological and hormonal factors influence political activity, I am not suggesting that rulers do not rely heavily on their higher critical faculties as well, which certainly are necessary for managing the complexities of government and the formulation of economic and social politics. It is a matter of emphasis. In the arts and sciences, the creative and problem-solving activities of individuals seem to stem from the natural curiosity and exploratory activity often shown by our simian ancestors, which seem to be more evolutionarily advanced forms of mental activity than the expression of dominance, aggression, and territoriality, which are common to ruling but are likewise found in many lower forms of animal life. In the arts and the sciences, man’s higher cognitive functions are put to use largely in the service of his curiosity about the world and himself, whereas in his striving for ultimate power they are put to use for the expression of the even more primitive instincts found in animal life forms antedating the existence of monkeys and apes.

There are other differences between the arts and sciences and politics to consider. Within the arts and the sciences, individuals give performances, produce works, or create actual products that bear their personal mark and become identified with them. In politics, aspiring leaders come to power through fulfilling certain social expectations and winning people over to them. Because they usually have no identifiable work product attributed exclusively to them other than their ability to get others to comply with their wishes, people’s reaction to them often depends more on their personal biases, beliefs, and vested interests than on any critical appraisal of a specific body of work. Instead of depending on brilliance, breadth of knowledge, creative problem-solving, or special talents, which are necessary for achievement in the arts and sciences, many would-be rulers seem to rely more on cunning, courage, physical prowess, deception, and power tactics to ascend the social hierarchy and gain ultimate power. That is why becoming a ruler requires no special academic training, artistic skills, or even superior intellect. That is why charisma, oratory, manipulation, and intimidation are often more important than wisdom, special expertise, and administrative experience. Humans have evolved more sophisticated and civilized methods than other primates for awarding leaders power, such as election campaigns, constitutions, and rules for succession; but, when you strip away all the trappings, the different ways that aspirants for high office jockey for power over others and keep it seem remarkably similar at times to those of our simian kin. And in many instances, such as when potential rulers resort to assassinations, wholesale killings, or armed conflicts to gain power, the human methods seem even more primitive.

It is not my intention to review the vast literature on primate behavior. Most readers are already familiar with the importance of dominance hierarchies, the breeding advantages of the alpha male, the numerous challenges by other males to topple the reigning leader, the formation of alliances among chimps to reduce the power of the alpha male, and the responsibilities of the leader to his troupe. As such pioneers in the field of primatology as Jane Goodall, Dian Fossey, and Robert M. Sapolsky have shown,2 the resemblances between how chimps, gorillas, and baboons establish dominance and how humans do are striking. In his trail-blazing books, Chimpanzee Politics and Peacemaking among Primates, Frans de Waal3 describes certain political behaviors in chimps that resemble those in humans. Certain animal purists criticized de Waal for “anthropomorphizing” the activities of chimps; that is, imputing human motives to their behaviors instead of interpreting them as unique to chimps. My approach, which mirrors his, may evoke a more negative reaction. I shall be interpreting the political activities of humans on the basis of behaviors observed in chimps, baboons, and gorillas, “simianizing” or “primatomorphizing” them, if you will. Now, that does not mean I do not see many kinds of political behaviors as unique to humans, with no obvious analogue in other primates. There are important differences. For instance, although humans and baboons may fight among themselves, dominate others, and keep harems, only humans have the ability to give pious excuses for what they do.

UNSEEN FORCES AT WORK

A Head for the Body Politic

As a result of my studies, I have come to the conclusion that the reason people want to rule is the same reason all societies want a ruler: It is part of the natural order of things. Just as every person needs a head, every society needs a leader. Just as any head with a brain will do for controlling the body, any leader will do for controlling the body politic. The existence of a leader is simply a matter of completeness. This may seem like a trivial observation on my part, but it is not. It has enormous implications. The compelling need for a leader, often any leader, is the only way to account for many of the rulers who have emerged during this past century. Just as the brain serves as a nerve center for integrating all the incoming messages from the physical body, the leader assumes executive control of the social body, with responsibility for coordinating the actions of its component parts. Not every brain lets the body function optimally. Likewise, there is no rule that a leader will carry out his social role wisely or well; he simply needs to do it. Except for rare periods of social anarchy or political chaos, there always will be a leader or, if not, a multi-headed ruling body until a suitable leader emerges, because the body politic cannot function independently on its own.

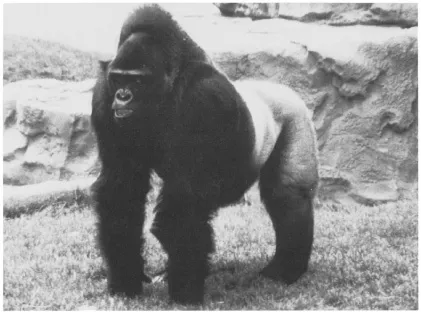

To demonstrate that my notion about the importance of a single leader serving as the head of a social body is not entirely fanciful, I cite the observation made by G.B. Schaller, who conducted the classical study on mountain gorillas, on the central role of the leader in the gorilla community.4

The focal point of each group is the leader, who is, without exception, the dominant silver-backed male. The entire daily routine—the time of rising, the direction and distance of travel, the location and duration of rest periods, and finally the time of nest building—is largely determined by the leader. Every independent animal in the group, except occasionally subordinate males, appears to be constantly aware of the location and activity of the leader either directly or through the behavior of animals in his vicinity. Cues reflecting a changed pattern of activity are rapidly transmitted through the group and the subsequent behavior of the members is patterned after that of the leader. This response insures cohesiveness and co-ordination of action. The complete adherence of gorillas to one leader must be considered in all discussions of groups, for variations in behavior between groups tend to reflect individual idiosyncracies of the leader.

1.1: Silverback gorilla. Between the ages of nine and ten, adult males turn silver. Blackbacks have been reported to turn silver prematurely after assuming leadership. Photograph by Nancy Staley/WRPC AV Archives.

What G.B. Schaller observed with respect to the importance of a leader for mountain gorillas, I claim also applies for humans, although perhaps in less dramatic ways. From the vantage point of the social unit, it probably makes little difference if the leader is brilliant, fair, capricious, stupid, or insane, just as it makes little difference for the existence of a family unit if either parent has those qualities. That does not mean a social unit is as well off with a deficient head as with a competent one; it only means that a country can exist as a social unit with one or the other. What matters is that the country has an acknowledged leader to guide it and that he stays in charge until someone else replaces him. In such a political cauldron, you would expect to find a wide range of personality types among rulers having no single attribute in common except for their fervent desire to rule—a situation, as you will see, that corresponds to what actually exists. Although rulers drawn to certain kinds of rule share certain features, rulers in general come from all levels of society; represent every race, color, and creed; show the gamut of intelligence and imagination; and have almost every kind of quality.

The need for a single leader to be head of a social unit seems biologically and psychologically rooted in our being. It is part of the genetic blueprint that governs our lives. The drive to be the alpha male provides the basic impetus for the dominance hierarchy, which, with the apparent exception of the bonobos,5 seems to govern most social interactions among higher primates. In humans, this need for a strong male leader becomes powerfully reinforced within the family unit. Born as helpless infants, people could not survive without their parents to nourish and protect them during their early years of dependency. Almo...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Introduction

- 1. Why Rulers Rule

- 2. It’s a Man’s World

- 3. The Perks of Power

- 4. A Dangerous Game

- 5. Rearing Rulers

- 6. Little Acorns into Mighty Oaks

- 7. Of Sound Mind??

- 8. The Measure of Political Greatness

- 9. The Seven Pillars of Greatness

- 10. Warmongers or Peacemakers?

- Appendix A: Sample of Rulers

- Appendix B: Methodology

- Appendix C: Data Collection and Statistics

- Appendix D: Political Greatness Scale

- Notes

- Statistics

- Acknowledgments

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access King of the Mountain by Arnold M. Ludwig in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Political History & Theory. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.