1. Japanese Advances and Retreats

Few examples in the history of warfare would match the success of the Japanese during the first six months of World War II. Once Imperial General Headquarters made the decision that Japan's future could be secured only by aggressive actions against the United States and its Pacific allies, it set in motion a series of attacks that were, in retrospect, gambles of the highest order. The first of these, the strike against Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941, was perhaps the biggest gamble of all, but the attack was absolutely necessary if Japan was to carry out its plans for further expansion in the Pacific and Southeast Asia, and it was the key to Japanese victories elsewhere in the ensuing months. Some later critics have faulted Admiral Chuichi Nagumo for not continuing his attacks against the vital docks and the supply and storage areas of Oahu, but he had succeeded in his primary mission of neutralizing the powerful United States Pacific fleet. The damage wrought during the few minutes of that raid canceled all immediate offensive plans of the United States and made defense the only possible alternative for the military planners in Washington and Pearl Harbor.1

The second gamblers' throw was to send an army and naval force against the British in Malaya. Operating against superior numbers of British and Australian troops, General Tomoyuki Yamashita conducted a most brilliant rapid advance in difficult terrain, which culminated in the capture of Singapore on 15 February 1942. The British fleet in the Indian Ocean was largely neutralized by the air attacks on Admiral Sir James Somerville's force, during which the battleships Prince of Wales and Repulse were sunk. Simultaneous actions had begun against the Phillipines on 8 December 1941, and successful Japanese air attacks destroyed almost all the U.S. fighter and bomber force on Luzon. Although the Japanese timetable for conquering the main Philippine islands was set back by the heroic defense of Bataan and Corregidor, the final issue was never in doubt since there was no reasonable possibility of reinforcing General Douglas MacArthur's outnumbered force. General Masaharu Homma, although dissatisfied with the progress of his army, all but finished his task when the Bataan defenders surrendered on 8 April 1942.2

These early victories were complemented by others—the conquest of Wake Island, the occupation of Hong Kong, the defeat of the British in Burma. Finally, in March 1942 one of their major goals, the petroleum-rich Dutch East Indies fell to the Japanese. Everywhere the Japanese navy and army had been successful. The Pearl Harbor stroke had assured the commander of the Japanese Combined Fleet, Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, of short-term naval dominance of the Central and South Pacific. During the early months of 1942 only token Australian forces stood in the way of Japanese occupation of New Guinea and ultimately, perhaps, even the conquest of the sparsely inhabited continent of Australia itself.

Yet the rapid and, in some cases, unexpected successes in all areas had negative overtones also. Imperial General Headquarters, enamored of the victories, did not assign clear priorities to its objectives. Instead, Japanese naval, army, and air forces were spread thin over the vast area of Southeast Asia and the Pacific. As a result, commanders in the field had insufficient forces in any one region to achieve the necessary intermediate objectives. This was certainly the situation facing the Japanese commanders in the southernmost part of the newly conquered Co-Prosperity Sphere. The lack of troops and materiel was one major factor in the failure of the Japanese to take Port Moresby and place themselves in a position to threaten northern Australia directly.

Those first months of the war proved to be a heady experience for the Japanese commanders; throughout much of 1942 they blithely advanced their plans for continued offensive operations, despite the fact that Allied strength was slowly recovering from the devastating blows delivered earlier. On 8 and 9 March a large Japanese task force stood off northern New Guinea and landed troops at Lae and Salamaua. Two days later the Japanese had secured Finschaven to the north. Within a few weeks radio stations and airfields had been established at both Lae and Salamaua.3 Thus the Japanese before the end of March were firmly established on the north coast and were ready not only to expand their lodgments but to move southward over the Owen Stanley Mountains toward Port Moresby. The only definite resistance they met, a portent of the future, was the air strike delivered by ninety planes from the Enterprise and Yorktown. Flying over the seven-thousand-foot-high mountains, it caught the invading transports and their naval escorts by surprise on 10 March. This raid on Lae and Salamaua sank four transports and damaged thirteen others. The Japanese casualties were 130 killed and 145 wounded. It was the worst loss of ships and men to their southern forces since the war began.4 Still, this daring U.S. air raid had little effect on the Japanese control of the Huon Peninsula and the entrance to the Bismarck Sea.

Earlier, on 23 January, an amphibious force of the Japanese 4th Fleet, supported by Admiral Nagumo's carrier striking force, had landed at Rabaul on New Britain. The small Australian garrison was overwhelmed, and soon the Japanese had extended their control over northern New Britain and neighboring New Ireland. Despite these successes, the offensive halted. The entire southern area was considered of secondary importance; the Japanese High Command was more concerned with operations in Malaya, Burma, and the Indian Ocean area, where Nagumo's carrier striking force was sent next. Also Admiral Yamamoto was planning to expand the Japanese main line of defense far to the east by occupying Midway Island. Thus, what many Japanese leaders later called the victory disease played an important role in stopping their heretofore relatively unimpeded southern offensives. The Japanese, so confident of ultimate victory and buoyed by their early successes, believed that they could continue those advances in all directions and in all theaters. One who disagreed was Admiral Shigeyoshi Inouye, commander of the 4th Fleet in charge of the offensives in the Central and South Pacific. From February on, he bombarded his superiors with requests for more ships and men in order to take Port Moresby, occupy the Solomon Islands, and thus directly threaten the long, tenuous American supply line to Australia and New Zealand. It was not until April that all was in place for a combined operation to seize crucial Port Moresby. Even then, the plan, called Operation MO, was not based on the overwhelming numerical superiority the Japanese could have brought to bear. Rather, they attempted the invasion with a much smaller task force than Inouye wanted.

The complex MO invasion plan was thwarted by the only Allied force readily available, the carrier task force of Vice Admiral Frank Jack Fletcher. The subsequent battle for the Coral Sea, fought on 7-8 May, cost the Americans two cruisers and the carrier Lexington from their depleted force in the South Pacific; in return they sank the small carrier Shoho and a few small craft at Tulagi. The action, fought completely by the air arms of both navies, was a tactical victory for the Japanese but undoubtedly a strategic victory for the United States. The eleven transports carrying the Japanese 3d Naval Landing Force and the army's South Seas Detachment, which were scheduled to take Port Moresby, were turned back.5 For Australia, the Coral Sea engagement was one of the most significant of the entire war.

The Allies were forced to counter a further threat to the vital port on 22 July, when General Tomitaro Horii landed sixteen thousand men at Buna on the north coast. After consolidating his position there, he sent his troops south over the Kokoda Trail with the objective of capturing Port Moresby. Opposed by the Australian infantry of the 7th Division, which they outnumbered, the Japanese struggled through thick jungle, across nearly impassable streams, up over the Owen Stanley Mountains, of which some peaks rose higher than thirteen thousand feet. By mid-September 1942 they had reached the southern foothills just a few miles from Port Moresby. Here they were halted by the dogged determination of the Australians, together with exhaustion and sickness in the Japanese ranks and the demands made by the Guadalcanal operation. Meanwhile, Australian troops and American combat engineers stopped the second prong of the Japanese thrust, a landing at Milne Bay in eastern Papua.

The Japanese would never get any closer to Port Moresby. What was left of Horii's command retreated to Kokoda in September, pursued by reinforced Australian units now confident that they could beat the Japanese in any environment. Kokoda fell to them in October, and in November the American 32d Division was given the unenviable task of taking Buna, which finally fell on 2 January 1943 after some of the bloodiest fighting of the war to date. The last Japanese bastion in this vital area of the north coast, Sanananda, was captured on 22 January. The defense of eastern New Guinea had cost the Allied command eighty-five hundred casualties, including three thousand dead, but Port Moresby was secure, and the Allies had regained the offensive in New Guinea, never again to relinquish it.6

Shocked by the rate of Japanese conquests in all theaters during the first months of the war, the Allies confronted the enemy with a highly divided command structure. The short-lived ABDA (American, British, Dutch, Australian) command in the Dutch East Indies exemplified how disastrous such division could be. A similar set of problems handicapped the British, Americans, and Chinese who were attempting to halt the Japanese in Burma. Finally, in late March 1942 the Joint Chiefs of Staff reached an agreement on how to divide command responsibility in the Pacific theater. Accepting the reality of the areas where the war was being fought, they divided ultimate responsibility between General Douglas MacArthur in the Southwest Pacific area and Admiral Chester Nimitz in the vast Pacific Ocean areas extending from Alaska to New Zealand. Nimitz kept direct command over the most crucial portion, the Central Pacific, and allowed his subordinate commanders in the North and South Pacific considerable freedom in decision making.

The south had particular autonomy after October 1942, when Vice Admiral William F. Halsey assumed command from his predecessor at Noumea, Vice Admiral Robert Ghormley. The Southwest Pacific theater included Australia, New Guinea, the Solomon Islands, the Philippines, and all the Netherlands Indies except Sumatra. The eastern boundary of the Southwest Pacific area was arbitrarily established at longitude 159° east, but this division proved unworkable. Already, in late 1942, the Solomons presented a problem. The projected invasion of Guadalcanal should by definition have been under MacArthur's command, but logic dictated that it be directed from New Caledonia. The competing headquarters agreed to give the Commander, South Pacific Area, control of the Solomons operation, but he was to cooperate fully with MacArthur's headquarters in Brisbane.7

Since the major ground actions to contain the Japanese offensives were at first all in the Southwest Pacific, most of the men and material supplied to the Pacific in 1942 went to MacArthur. Troops dispatched to the South Pacific were mainly to defend the islands guarding Australia's line of communications with Hawaii and the west coast of the United States. Although MacArthur, with some justification, complained bitterly against the “Europe first” doctrine of the Joint Chiefs, the fact is that between January and March 1942 nearly eighty thousand troops were sent to the Southwest Pacific. Before the end of the year more than a quarter of a million men would be under MacArthur's command. By midyear, the 32d and 41st American divisions had arrived in Australia to beef up The Australian forces. The 37th Division was in Fiji, the Americal Division was posted to New Caledonia, and the 147th Regiment was in Tongatabu—all guarding the vital supply routes to Australia and New Zealand.

In addition there had been a slow, almost reluctant buildup of air power in Australia. When Lieutenant General George Kenney arrived to take command of the 5th Air Force, he found the organization a shambles and almost totally committed to a defensive role. This was not surprising since the Allied fighter planes, P-39s and P-40s, were distinctly inferior to their Japanese counterparts above fifteen thousand feet. In July, in the South Pacific, Admiral John McCain, commanding AirSoPac, had fewer than three hundred planes of all types scattered from Samoa to Espíritu Santo. The most important component of his force prior to the Guadalcanal landings were two marine squadrons, which had been provided by Admiral Nimitz to give air cover for that invasion.8

Although the Japanese still had the upper hand in the vast southern areas and could still determine where to launch an offensive, they had been halted in New Guinea and by the close of the year would stand on the defensive at Buna. The Allies in both Pacific areas were slowly building up the necessary force not only to blunt those offensives but to turn the tide of the war. The three keys to the Allied reversal of fortune were northern New Guinea, the Battle of Midway, and the contest for Guadalcanal.

Admiral Yamamoto's belated, complex plan for bringing the bulk of the United States Central Pacific fleet into one final confrontation was put into motion in late May. He had concluded correctly that Admiral Nimitz would not allow the Japanese to occupy Midway Island without a struggle. He was not aware, however, of the degree to which the Japanese naval code was understood by the Americans. The ability to decode Japanese messages, together with a gambler's intuition, enabled Admirals Raymond Spruance and Frank Jack Fletcher to ambush Yamamoto's leading elements—his carrier striking force, commanded by the Pearl Harbor admiral Nagumo. Many experts have considered the Midway engagement, begun on 3 June, to be the most crucial of the Pacific War. Like the Coral Sea battle, it was fought entirely by aircraft. The following day witnessed the practical end to Japan's attempt to dominate the vast reaches of the Central Pacific. Dive bombers from the Enterprise and Yorktown struck Nagumo's carriers with devastating force. Before the end of the next day, 4 June, all four Japanese carriers—the Akagi, Kaga, Soryu, and Hiryu—had been sunk. Almost all of Japan's most experienced pilots were also lost. The Americans sustained minimal damage to the facilities on Midway Island, and the Yorktown and one destroyer were sunk. Without air cover for the main elements of his battle fleet and transports, Yamamoto did not dare continue with the invasion plans and ordered a general withdrawal from the area on 6 June.9

The Midway defeat had ramifications far beyond a mere tactical victory. Although the Japanese fleet remained a powerful force for another two years, it would never again be so dominant. American shipyards were already busy on the construction of new fleet carriers and fast battleships, which by mid-1943 would give Admiral Nimitz his hoped-for big Blue Water Fleet. Indeed, his concentration on building up the Central Pacific naval forces helped put Admiral Halsey at a disadvantage against the Japanese later that year, during the Solomons battles. Still, Halsey did not generally have to contend with enemy aircraft carriers; most of the Japanese ships involved in South Pacific operations were cruisers and destroyers. Yamamoto and his successor, Admiral Mineichi Koga, like Nimitz, concentrated on the Central Pacific, where they expected a further decisive battle would be fought.

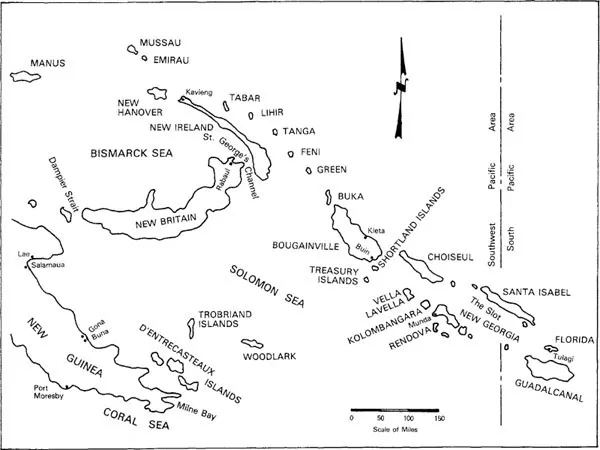

Japanese occupation of the Solomon Islands proceeded in an unhurried fashion during the spring of 1942 (Map 1). From the central base at Rabaul, General Hitoshi Imamura, in command of the 8th Area Army, and his naval counterpart, Vice Admiral Jinichi Kusaka, in charge of the Southeast Area Fleet, had their attention firmly fixed on Port Moresby. They were aware that no Allied force protected the many islands stretching southeast from New Ireland for over six hundred miles. Therefore, there was no reason to rush significant numbers of troops to any of these islands while the demands in New Guinea were still high. Nevertheless, key points on New Ireland were occupied in February, followed by landings adjacent to the Buka passage and on the east coast of Bougainville by the end of March. Then by the close of April a small force was sent to Tulagi in the southern Solomons, there to establish a seaplane base.

At first the Japanese paid little attention to the main southern island, Guadalcanal, located twenty miles from Tulagi across a stretch of open water that would later earn the name of “Iron Bottom Sound.” Then in mid-June, Japanese lower-echelon officers made the fateful decision to build an airfield on Guadalcanal. Within a month more than two thousand workers were clearing the jungle there and doing preliminary work for the airstrip. The discovery of this construction frightened Admiral Ernest King, the American Chief of Naval Operations, since it threatened to checkmate the American military buildup eastward in the New Hebrides. Land-based bombers sited on Guadalcanal would directly threaten Allied convoys bound for New Zealand and Australia. The Joint Chiefs on 2 July hastily decided to mount the first American offensive of the war, a shoestring operation code named WATCHTOWER.10

The decision to capture Guadalcanal came as a shock to both General MacArthur and Admiral Ghormley in Noumea. MacArthur's forces were attempting to halt Horrii's advance on Port Moresby, and he certainly could not spare his green reserves to open a new front hundreds of miles away. The assault force Ghormley was ordered to use was the 1st Marine Division, only one of whose regiments, the 7th Marines, had arrived. The rest of the division was at sea on its way to New Zealand. Admiral King had promised the commander of the “Old Breed,” Major General Alexander Vandegrift, that the unit would have time to prepare for its first combat, not projected until early in 1943. Instead, Washington issued orders to seize the airfield the Japanese were building on Guadalcanal now, shrugging off the objections of MacArthur and Ghormley, who were told to get on with the invasion. The only concession was to postpone D day until 7 August. Thus the overreaction of Admiral King and his staff began a chain of events that would culminate in the worst defeats suffered by the Japanese army and navy in the war up until that time. The battle for Guadalcanal was basically an encounter conflict; neither side had planned for a decisive meeting, but once engaged, neither would pull back.

Map1. SOLOMON ISLANDS AND ADJACENT AREAS

The early stages of the battle for Guadalcanal were replete with bad planning and errors on both sides. The projected covering force for Vandegrift's marines contained three of the four carriers the United States had in the Pacific, in addition to a new battleship and a division of Australian cruisers. Admiral Fletcher, who had his misgivings about the entire operation, made it clear, however, that he would not risk his carriers to protect the amphibious force. The commander of that force, Rear Admiral Richmond Kelly Turner, argued that he would need four days to get al...