- 360 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

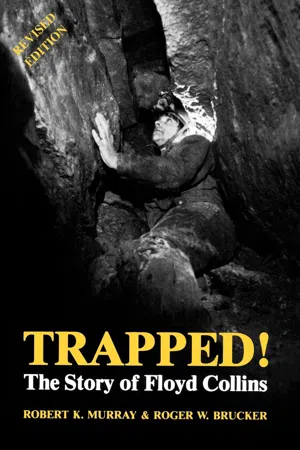

When Floyd Collins became trapped in a cave in southern Kentucky in early 1925, the sensationalism and hysteria of the rescue attempt generated America's first true media spectacle, making Collins's story one of the seminal events of the century. The crowds that gathered outside Sand Cave turned the rescue site into a carnival. Collins's situation was front-page news throughout the country, hourly bulletins interrupted radio programs, and Congress recessed to hear the latest word. Trapped! is both a tense adventure and a brilliant historical recreation of the past. This new edition includes a new epilogue revealing information about the Floyd Collins story that has come to light since the book was first published.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Trapped! by Robert K. Murray,Roger W. Brucker in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

To Find a New Cavern

The cave was only a short distance from Bee Doyle’s house, and Floyd covered the ground quickly. It was not a morning to loiter. A chill westerly had pushed back the rain clouds, which, for the past two days, had brought extreme dampness to the area, and only a weak sun shone through. Winter runoff dripped everywhere and the earth underfoot was in a semisolid state that was neither ice nor mud.

Except for the battered kerosene lantern and a seventy-two foot rope slung over his shoulder, Floyd could have been any Barren County farmer setting out to cut ties for the Louisville & Nashville Railroad or to examine his land for winter damage. Floyd, however, was on a different mission this day. Earlier he had eaten a breakfast of salt pork, potatoes, corn bread, and a quart of coffee. Between bites he had told a worried Doyle that everything was going to turn out all right. Floyd smiled to himself as he recalled Doyle’s face. There was really nothing to be alarmed about—he had been through more difficult situations before. Floyd’s smile suddenly faded as he continued his brisk pace. He should not have told Miss Jane about the angels and the falling rock. She had gotten everyone excited, and he remembered the ensuing family squabble with distaste. Old Man Lee had raged at his foolishness, and even Homer had failed to come to his defense.

Floyd descended a slippery path that skirted a cliff, and made a left turn. He admitted to himself that he would be glad to have this part over with. For three weeks he had been digging in this hole, trying to pick his way through the dangerous, crumbling passageway to solid limestone below. Four days earlier, he had set off a charge of dynamite to remove some of the last obstacles that blocked his path. Now it was mainly a matter of wriggling past the shattered rocks. During the last two days he had built fires at the cave’s mouth hoping that the heat would dry it out. Alternate snow, freezing rains, and a mid-January thaw had turned the ground into a saturated sponge. At best, it was going to be a wet crawl.

The cave loomed ahead. The overhang of sandstone above it was splotched with patches of moss and lichen and was etched and split into sections like layered brick. Extending out about fifty feet, this ledge sheltered a circular area forty feet in diameter. At the back wall on the left was a passage entrance. To reach it, Floyd had dug out a crawlway—a trench roughly six feet deep and four feet wide. Shaded from the light, it led into the gloom. Arriving there, he took off his heavy outside woolen coat and hung it on a projecting rock. He figured he would still be warm enough and he needed to reduce his hundred-and-sixty-pound bulk for the work to come. Clothed in rough overalls, a blue jumper, a woolen shirt, and ankle-high hobnailed boots, Floyd now looked like what he was—one of central Kentucky’s cavers. Somehow, though, he seemed older than his thirty-seven years, his face appearing gaunt behind a long, sharp nose, deep-set eyes, and a prominent gold front tooth. Hurriedly, Floyd lit his lantern, readjusted his rope, and ducked inside.

To many, a man who would crawl around under the earth rather than cultivate its surface might seem like a shiftless sort. Floyd Collins was not. Caves provided his livelihood. Moreover, the same spirit that led others to scale mountain heights caused him to go into the depths. Even now, despite the danger, he thrilled at the thought of exploring the underground unknown. Ever since he had started to work in this cave in early January, he had been convinced that its treacherous passageway would lead to marvelous discoveries below, and he was determined to find them. Besides, they might also make him rich.

The cave’s entrance passage sloped slightly downward for about fifteen feet and ended in a four-foot drop at a small square hole through which Floyd gently lowered himself. Bearing to the right, he was shortly forced onto his hands and knees as the passageway doubled back under itself once. The path then twisted and turned and divided into a number of false leads between tumbled limestone blocks before it narrowed to a squeeze that caused Floyd to squirm in order to get his body through. The way enlarged temporarily as it continued down at an angle of almost ten degrees. Suddenly it pinched to barely ten inches high, and bent sharply to the right. Not long afterward, the passage heightened into a small chamber that allowed Floyd to sit up. Here, earlier in the week, he had placed a crowbar, a shovel, and some burlap bags he had used for removing loose gravel and rock. He picked up the crowbar, lowered himself into the continuing passage, and resumed crawling on his belly. Shortly, he arrived at another squeeze, which opened into a ten-foot pitlike chute. At the bottom of the chute was a cubbyhole the size of the inside of a kneehole desk. Leading out of it was a crack about the circumference of a large wastebasket.

Floyd was now a hundred and fifteen feet from the mouth of the cave and fifty-five feet underground. He had reached this point several times before, but had always been stopped by a pile of rocks, a terminal breakdown. However, Monday’s dynamite blast and his subsequent removal of the rock fragments had opened the way for him to continue. Here, in the bottom of the chute, there was so little room that he had been forced to work upside down to scrape out the last of the loose material. Today, he turned feetfirst into the chute and, hunching the rest of his body up in a ball, eased himself cautiously through the cubbyhole and into the crevice. He moved his rope coil ahead of him, shoving it as far as his arms could extend. Then he pulled himself out and repeated the procedure, this time pushing a lantern and checking some of the jagged ceiling rocks for stability as he went. Because this hole was a burrow through limestone rubble, it did not have solid bedrock sides and ceiling. Extreme care was therefore necessary. As Floyd moved again into the crack, he noticed the roof was one huge limestone block for a distance of about four feet. But the remainder of the ceiling was loose with smaller rocks protruding. One, which Floyd guessed to weigh about a hundred pounds, hung ominously down at the narrowest part of the crevice. Skillfully, he moved past it.

Floyd emerged onto a narrow ledge, caught his breath, and peered into a hole some sixty feet deep. Since its sides were sloping, he tied his rope to a boulder and descended easily with its aid. The walls of this pit appeared dark gray in his lantern light and revealed nothing interesting. If there was a “big cave,” it still lay beyond. Yet Floyd was excited because this deep cavity gave promise of new passages out and down, and he looked around for possible leads. Suddenly his lantern flickered, telling him he had better leave. No matter, he thought. There would be ample time to explore further after he told Doyle and the others what he had found. Laboriously, he rope-walked his way up the steep pitch to the ledge above. He decided to leave the rope tied where it was because he could use it again later. Then, perspiring freely, he pushed his lantern ahead of him in the crevice as far as he could reach, turned over on his back, and entered, inching his body along by hunching his shoulders, twisting his hips, and pressing his feet against the walls and the floor.

At the narrowest part of the fissure he again moved his lantern ahead, this time shoving it into the cubbyhole, where it toppled over and went out. Floyd had been plunged into darkness many times before and it did not bother him. But in this particular situation it was a nuisance not to have light. He tucked his arms along his sides, compressed himself as flat as possible, and again began to combine shoulder and hip motions to wiggle through. Bringing his feet into play, he dug them hard into the sides and floor of the crack for better leverage. He guessed that he was just now emerging from under the large limestone block and kicked out with his right foot for a final surge. Inadvertently, he struck the hanging rock that he had so carefully avoided on the way in. It broke loose and fell. At that precise moment, Floyd’s left foot was in a small V-shaped indentation in the floor of the crevice and the falling rock, dropping across his left leg at the ankle, pinned his left foot there. Hoping to free it, he kicked again with his right foot. This dislodged more rocks from above, further trapping his left foot and then his right one as well.

Floyd’s head was lying toward the cave’s entrance, just at the cubbyhole in the bottom of the ten-foot chute. He was reclining as if in a barber’s chair, lying on his left side at an angle of about forty-five degrees. His left arm was partially pinned under him, his left cheek rested against the floor rock, and his right arm and hand were held close to his body by the crevice wall and the limestone boulder above. Coming to within a few inches of his chest, this block’s flat undersurface prevented him from turning over. Entirely surrounded by rock and earth, Floyd was in a coffinlike straitjacket. His feet were pinned, his left hand and forearm could move only slightly, his right hand and arm were useless, and he could not roll over.

Panic seized him. Since he was in the dark, he could not fully assess the damage, but he knew he was in trouble. He first worked his abdominal and thigh muscles, struggling to free his feet. Next, he clawed at the gravel sifting around his legs. This loosened more debris which slid slowly onto his body, and soon his fingertips oozed blood from the futile effort. He twisted and humped his torso for relief from the sharp stones grinding into his back, but his lunges only shook down more dirt from above. Fragments of rock and sand drifted in around him, wedging his body more tightly and eventually immobilizing even his hands. When his panic finally subsided, he lay still, realizing belatedly that his every movement made his predicament worse. Over the wild beating of his heart, he could hear the soft rivers of dirt still sliding downward.

Although he knew it was useless, Floyd began to yell. He had no idea how long he screamed, but he soon lost his voice. Then he began to shiver. He was cold and wished he was wearing his heavy woolen coat. He felt miserable in his wet and sweaty clothing, and his left leg throbbed with pain. To add to his discomfort, a stream of water was running across the underside of the limestone boulder and a small tributary was dripping onto his face. Worse, his bladder felt like it was going to burst. Oh, God, he thought, I’ve got to piss! Was anyone ever trapped this way? To lie here even a few moments was agony; for hours it would be unbearable.

At last Floyd began to pray. Harboring vestiges of a hard-shell Baptist upbringing, he fervently begged God to help him. Finally, he lost track of time. He dozed fitfully, waking on several occasions but always mercifully slipping back into sleep. For now, exhaustion was his kindest friend, supplying the necessary drug that made his plight at all endurable. Jumbled thoughts alternated with his fretting and sleeping, but throughout he retained the belief that someone would ultimately find him. He had entered the cave at ten o’clock that morning. Along about noon, he had been trapped. Bee Doyle knew where he was and would surely begin searching for him when he failed to return. Doyle would raise the alarm, reasoned Floyd, and then aid would come.

That was Friday night, January 30, 1925.

The Green River in central Kentucky is formed from trickles that drain through limestone beds which, according to the natives, give the water a flavor that makes a lip-smacking whiskey. By percolating down the joints and fractures of this same limestone, the water also carves out fantastic subterranean caverns.

This process has been going on for 20 million years. Since the Tertiary period, water has seeped through the underlying Kentucky rock, gradually dissolving away the limestone and forming openings that over time have enlarged and become joined. Disintegration of the limestone has also continued on the top, bottom, and sides of these openings, and the draining water has cut passageways that interconnect at several levels. Simultaneously, water penetrating down and through the rock has not only created vertical shafts, horizontal tubes, and canyon passages, but has left behind spectacular crystalline formations on its way to reach the Green River.

Geologically known as the Central Kentucky Karst, this area is part of a huge limestone belt extending from southern Indiana, through Kentucky, and into Tennessee. More than elsewhere, however, the surface of the Central Kentucky Karst is riddled with sinkholes and its underground is shot through with caves. Literally thousands of them honeycomb the landscape. Appearing as depressions on the land’s surface, the sinkholes are prominent funnels through which water seeps to seek its hydrological base at the Green River. The caves range from the simple (containing one passage of no more than a few yards) to the complex (possessing miles of interconnecting shafts and passageways). Historically and geologically, the most famous of these is Mammoth Cave, which has given its name to the entire surrounding region. Mammoth achieved notoriety almost fifty years before the California Gold Rush and before Yellowstone or Yosemite were even heard of. Over the years other caves have become known and commercially developed in Kentucky’s cave region: Hidden River Cave, Diamond Caverns, Great Onyx Cave, Mammoth Onyx Cave, Crystal Cave, and Colossal Cavern, to name only a few.

Interest in Kentucky’s caves has not been just a modern phenomenon. Three to four thousand years ago prehistoric peoples knew about the caverns and used them for various purposes. These ancient visitors left remnants of torches, sticks, and canes, as well as bone fragments, human feces, and at least five desiccated bodies as mute testimony to their presence. About thirty-five hundred years ago, prehistoric groups actually made their camps in Mammoth Cave and Salts Cave. With underground temperatures hovering at a year-round 54° F., these two caves provided shelter and comfort against the cold winter winds and the hot summer temperatures above. Walls and ceilings of parts of both Salts Cave and Mammoth Cave remain blackened to this day by the torches and fires of these prehistoric men.

There is also evidence that these prehistoric cavers mined the caves. They were interested in chert (a dull-colored flintlike silica), gypsum (a white powder that produces paint or plaster when heated and mixed with water), and mirabilite (a laxative and a salt substitute). Remains of human feces near quantities of mirabilite suggest that ancient peoples came there to cure their constipation. In 1935, a prehistoric body was discovered trapped under a seven-ton boulder in Mammoth Cave. The victim had been mining gypsum when he was crushed by the rockfall. Ancient men also engaged in some exploration of the caves. Several of their explorers ventured at least two miles back into the caverns. Torch fragments composed of reeds from the banks of the Green River indicate their routes. At least two sets of bare footprints preserved in mud reveal that a man and a woman followed interconnecting passages from Salts Cave to Unknown Cave, a remarkable feat. There is a question, however, about how much the successor to ancient man, the American Indians, knew of or used the caves. We know that they visited them but we have no evidence of their deep penetration.

According to popular myth, the first white man to show an interest in the Kentucky caves was a frontiersman named Houchins who chased a bear into the mouth of Mammoth in 1797. The next year, 1798, Valentine Simons registered a two-hundred-acre survey known as the “Mammoth Cave Tract,” and began leaching saltpeter out of it. Mammoth’s earth contains calcium nitrate, derived from nitrogen-fixing bacteria in the cave soil. But before it was suitable for making gunpowder it had to be converted into potassium nitrate, or “true” saltpeter. Simons operated such a conversion works just inside the mouth of the cave prior to the War of 1812. However, the low price of the product barely enabled him to survive, and in that year he sold Mammoth to Charles Wilkens, a saltpeter dealer, and Hyman Gratz, a wealthy Philadelphian. Happily for the new owners, the war suddenly dried up all overseas sources of saltpeter and the price soared. For a time Wilkens and Gratz even found it profitable to import gangs of slaves to work the cave’s deposits.

After the war the demand for saltpeter again declined, and Mammoth began to be exploited as a tourist attraction. The discovery of ancient bones and a mummy helped fuel popular interest, and several eastern newspapers began publishing articles about the cavern. In 1828, Gratz took advantage of a drop in land values to buy out Wilkens and, expecting to capitalize on the tourist trade, added to his holdings until he owned about sixteen hundred acres. He also built a rustic inn with sleeping quarters at the cave in order to entice overnight visitors. But the venture failed as the frontier moved rapidly westward, leaving Mammoth in the backwater.

For a decade the fortunes of Mammoth remained at low ebb. Then, in 1838, Franklin Gorin of Glasgow, Kentucky, purchased the tract from the Gratz family for $5000, enlarged the rustic lodge to accommodate forty persons, and rechristened it the Mammoth Cave Inn. Gorin appointed as cave guide a slave named Stephen Bishop, who became one of the most famous cave explorers in the region’s history. Although only seventeen years old at the time, Bishop skillfully added variations to the scenic tourist route and developed an attractive spiel. A self-educated man, he displayed a remarkable range of wit and humor and acquired considerable familiarity with geology. In his spare time he explored the depths of Mammoth on his own and discovered what are now called Gorin’s Dome, the River Styx, Pensacola Avenue, Bunyan’s Way, and Great Relief Hall. He also caught and displayed the first cave blindfish.

Gradually more tourists began to arrive at Mammoth, and by the spring of 1839 Gorin was doing a modest business. But his capital and foresight were limited and late in that same year he sold the cave, the inn, and Stephen Bishop for $10,000 to Dr. John Croghan, a Louisville physician. Croghan immediately converted the inn into the Mammoth Cave Hotel and, with the aid of the Kentucky legislature, got one road constructed from Cave City to Mammoth, another from Rowletts to Mammoth, and a third from Dripping Springs. These routes across semiwilderness permitted the Louisville and Nashville stage to reach the cave and stop overnight. As a result, Mammoth became a regular station on the way from Louisville to Nashville, offering travelers cave tours, rooms, and meals.

Bishop, in the meantime, added new delights to the cave trips by his continued discoveries—Mammoth Dome, the Snowball Room, and Cleaveland Avenue. Ultimately a visitor could select a guided tour of from two to nine miles. Bishop also drafted a map showing the various underground chambers and gave printed copies to the cave’s guests. But Bishop did not share all of the cave’s secrets and continued to make private explorations far beyond the end of the tourist trails. Because of what he found, he began to suspect that all of the caves in the Mammoth region were somehow interconnected.

In 1849, Croghan, a bachelor, died of tuberculosis, leaving Mammoth in trust to a succession of nieces and nephews. In his will he granted Stephen Bishop his freedom at the end of seven years. Ironically, only one year after Bishop was freed he also died, a young man of thirty-six. By that time the expansion of steamboat traffic, the connecting stage lines, and the completion of the Louisville & Nashville Railroad brought an ever-increasing number of tourists to the cavern.

The Civil War hurt Mammoth. Radical Reconstruction and continuing North-South animosities also worked against the tourist trade. Yet there were always those who were willing to brave almost any hardship to enjoy the sights of Mammoth, including such famous persons as Jenny Lind, the Swedish Nightingale, who is said to have sung arias under the arches in Gothic Avenue, and the actor Edwin Booth, who set the walls to ringing with Hamlet’s soliloquy. Still, a revival in tourism did not occur until the mid 1880s when a narrow-gauge spur of the L&N Railroad was built directly to the mouth of the cave. Known as the Mammoth Cave Railroad, it ran from Glasgow Junction (now Park City) to the cave’s entrance, a distance of nine miles. This service was first inaugurated in 1886, and the engine, “Hercules,” thereafter carried in its two coaches a maximum of forty passengers each way on two trips a day. Other innovations and improvements in facilities rap...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Prologue

- 1. To Find a New Cavern

- 2. Friends and Relatives

- 3. The Outside World Intrudes

- 4. Human Chains and High Hopes

- 5. Final Contact

- 6. The State Takes Over

- 7. Carnival Sunday

- 8. Investigation and Frustration

- 9. The Struggle Ends

- 10. Making of a Legend

- Epilogue

- Epilogue 1999

- Notes on Sources

- Index