- 306 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

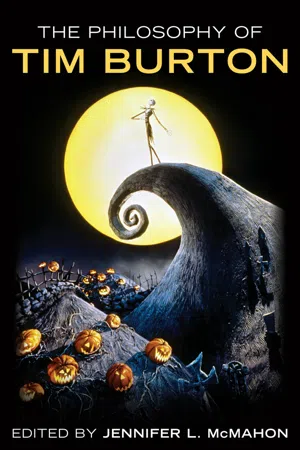

The Philosophy of Tim Burton

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Philosophy of Tim Burton by Jennifer L. McMahon in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Philosophy & Film & Video. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part 1

BURTON AND IDENTITY

FISHING FOR THE [MEDIATING] SELF

Identity and Storytelling in Big Fish

The selfhood of oneself implies otherness to such an intimate degree that one cannot be thought of without the other.

—Paul Ricoeur

No son wants a delusional or dishonest father, but this seems to be the situation that Will Bloom (Billy Crudup) faces in Tim Burton’s film Big Fish (2003). Will is convinced that his father, Ed Bloom (Albert Finney), is an irresponsible liar whose self-proclaimed fantastic identity is delusional. The film’s setting brings father and son together one last time as Ed is confined to his deathbed. Though Will has not spoken to his father in three years, he returns home to be with him during his last days. In addition to dealing with the emotional intensity of preparing to bury his father and comfort his grieving mother, Sandra (Jessica Lange), Will desires to finally know the truth about his father’s life. Will wants his father to admit his failures and, in the process, denounce the long-standing narrative that he has constructed as a way of presenting his life.

“All the Facts, None of the Flavor”

Ed Bloom is a storyteller. He has authored his life around a series of tales, and it is through the retelling of his fantastic tales that he understands and posits the significant moments of his life. He answers the various questions that life poses him with a story, a story in which he is the main character, but one that also includes his son in the long-running narrative. As a boy, Will (Grayson Stone) enjoyed his father’s bedtime stories, but he has outgrown them. He refers to them as “lies” and he is embarrassed that his father continuously tells these tales. Will now seeks the “true versions of things, . . . of stories” related to his father’s past. He believes his father lived a “second life” with another family. Will suspects his father cheated in his marriage and that he was too preoccupied with himself to be honest with Will. Will claims to not know his father, and this distance troubles him. As Will puts it, “We never talked about not talking.” Frustrated, Will believes he is merely a “footnote” in his father’s story. The “truth is,” he claims, “I didn’t see anything of myself in my father, and I don’t think he saw anything of himself in me. We were like strangers who knew each other very well.”

Ed is aware that he is a storyteller, and apparently he is aware that the presentation of himself through story is his own construct: “That’s what I do. I tell stories,” he asserts to his imploring son. Certainly he has learned to see himself as unique and presents himself accordingly. The central story of the film is the story of a giant catfish that eats Ed’s wedding ring on the day of Will’s birth. Along with the story of his marriage, these are the two most prominent of many fantastic tales that Ed often retells. As his death looms, he wishes to retell to his son’s wife, Josephine (Marion Cotillard), the story of his marriage, grumbling that Will would have “told it [to her] wrong anyway—all the facts, none of the flavor.” The negotiation of ritual passages throughout Ed’s life—important events such as high school heroics, leaving home, getting a first job, serving in the military (and mistakenly being thought to have been killed in action), establishing a professional identity, getting married, and of course, becoming a father are all told and retold with customary flavor. But now Will wants truth, not tales. He tells his father, “I believed your stories. . . . I felt like a fool to have trusted you. You’re like Santa Claus and the Easter Bunny combined—just as charming and just as fake.” Defending himself, Ed angrily responds, “I’ve been nothing but myself since the day I was born and if you can’t see that it’s your failing, not mine.”

In this tender plot, accented with colorful flashback scenes featuring a young Ed Bloom (Ewan McGregor), Will confronts his father’s characteristic obstinacy while attempting to investigate the facts of his father’s life. His search brings surprising results, which are finally confirmed when the family doctor (Robert Guillaume), who was present at Will’s birth, announces the ordinary circumstances of Will’s origin and in the process absolves any lingering misperceptions concerning Ed’s apparent failures. Dr. Bennett brings Will to a point of recognition and confirms for the audience the harmless, even necessary manner and motive of Ed’s colorful identity.

In Big Fish storytelling is highlighted as a means of discourse. Though Will is a successful journalist, his investigative manner proves limited and pales when matched with his father’s colorful narrative. Interestingly, both father and son are aware of their preferred narrative styles: “We’re storytellers, both of us,” Ed tells his agitated son. “I speak mine out. You write yours down—same thing.” Clearly, the identity of both characters is vitally linked to their narratives, and as such the film offers a rich opportunity to discuss foundational philosophical issues concerning personal identity and the nature of the self. I shall focus on narrative accounts of identity, or what may be referred to as intersubjective accounts of the self. Proponents of these accounts maintain that self-identity is constructed as a narrative within a dynamic process of social and linguistic interaction, and they support the view of the self as a product of storytelling. After discussing the ways in which Ed Bloom’s storytelling persona illustrates more abstract philosophical accounts of the self, I shall also comment on the role of storytelling in societal discourse as exemplified in the happy ending of Big Fish.

Society and Self-Construction

Burton’s film suggests the importance of understanding narrative identity. In particular, it indicates that identity is best understood as an intersubjective construct. By intersubjective I mean the sharing of subjective states that affect human development. Through encounters with others sharing material space, physical interaction, and language, we develop the idea of the self, namely, a sense of who we are. Indeed, many modern philosophers would suggest that our identity is being formed before we ever reflect upon or conceptualize our own unique sense of self. The question of the self is a prominent one in philosophy. Theories of self-development and personal identity understandably connect to the way one sees the world, how one identifies others, how one judges others, and so forth. Given this, most philosophers eventually offer some commentary relevant to discussion of the human self, and the history of philosophy would suggest various ways of understanding the self. For example, some have believed the human self to be a carbon copy of a heavenly blueprint, whereas others have posited the self as a blank tablet upon which humans write selfhood into existence as a result of experiences. Metaphysical approaches to understanding the self often emphasize its a priori nature and claim the self to be independent of experience. For example, Plato (427–347 B.C.) suggests the empirical self is a mimetic reprint of an eternal soul. On the other hand, a posteriori positions hold that the self is a product of experience. Such views are held by philosophers who reject mimetic, essentialist accounts of the self and instead suggest that the self is a product of cumulating experience. For example, David Hume (1711–1776) argues that the human self is “nothing but a bundle or collection of different perceptions. . . . The mind is a kind of theater where several perceptions successfully make their appearance, pass, repass, glide away, and mingle in an infinite variety of positions and situations.” As this passage suggests, Hume denies the existence of an enduring self. Indeed, he goes so far as to refer to the self as a “fiction.”1 Considering the self as a “fiction” anticipates Ed Bloom’s storied self-presentation. Importantly, it introduces the notion of the self as narrative.

Much of contemporary philosophical discussion of the self originates with Rene Descartes (1596–1650), who famously identified the self as a “thinking thing” in his formula cogito ergo sum (I think, therefore I am).2 In fact, almost all modern discussions of the self in some way respond to Descartes’s characterization of the cogito as an independent substance. Bertrand Russell (1872–1970) summarizes the broad-ranging Cartesian effect on modern philosophy: “There is thus, in all philosophy derived from Descartes, a tendency to subjectivism.”3 The legacy of Descartes’s formula, however, is a dualistic mind/body dichotomy. While this view may have offered a sense of certainty in the seventeenth century, it is one that many modern thinkers reject, favoring instead a more holistic understanding of mind, body, and self. What modern critics suggest constitutes the self is not fully covered by the cogito.

In this chapter, I draw from several a posteriori philosophers who reject essentialist views of the self, philosophers who attempt to transcend the Cartesian formula and reject the notion of a substantive human soul or a “transcendent ego.”4 According to several prominent philosophers, the narrative account of identity posits the self as a psychosocial construct, a creation made on the part of society and the subject in and through linguistic interaction. These philosophical views recognize the interactive, reciprocal construction of what we generally call the self. The self, then, is not the discovery of an existing thing. Instead, philosophers who endorse a narrative account of the self believe that personal narratives are being written for us even before we are fully aware of the social influences that shape identity. An intersubjective account of the human self is one that sees the self as arising from human experience and language. Clearly, this view of selfhood offers an excellent basis for understanding Ed Bloom’s persona. Since selfhood is developed in a social context, narrative is a primary means by which human socializing is formed and reflected. Moreover, an intersubjective construction of selfhood provides critical understanding for dramatically illustrated depictions of the self in contemporary popular culture, specifically, in Burton’s Big Fish.

Jean-Paul Sartre: Consciousness as Prerequisite for Selfhood

When considering an intersubjective notion of human self, it is important to consider what makes selfhood possible in the first place. An important concept for understanding selfhood is found in the work of Jean-Paul Sartre (1905–1980). His major work, Being and Nothingness, rejects an essentialist, substantive view of human identity.5 Here Sartre denies that the self is substantive, eternal, or intrinsic to the human animal. Instead, he asserts that individual identity is a conceptual figure that evolves through experience. Specifically, Sartre argues that the human self is constructed over time as a result of ongoing interactions with others.

Being and Nothingness asserts that humans are profoundly affected by their material and linguistic surroundings long before they become reflective and aware of their own responses to such surroundings. Indeed, Sartre makes the role of social interaction clear when he characterizes human consciousness, in itself, as a nothing. As Sartre makes plain, consciousness is not a substantive thing. Just as the eye is distinct from what it sees, human consciousness is distinct from the material and linguistic contexts that eventually shape self-consciousness. For Sartre, consciousness is the negation of substance, a blank slate upon which human identity will eventually be formed. Consciousness, then, is the prerequisite for selfhood. However, it is not synonymous with it. Humans have consciousness but not intrinsic identity, so humans may be said to arrive on the scene with consciousness but not a self. Self-consciousness develops through the experiences that humans have, even experiences that begin long before reflective responses, and long before logical decision making. Human consciousness, developed over time through social interaction, eventually evolves to self-consciousness. Social interaction prompts both the internalization of socially assigned traits and reflection on the part of the individual. The internalization that begins in the prereflective states of human development literally forms the self. Eventually the reflective process makes possible the dissociation from that identity that was written for us before we became aware of those influences. Over time we become aware of those influences and begin intentional construction of personal identity. Sartre writes, “I see myself because somebody sees me.”6 Evolving from prereflective influences, self-consciousness is necessary for one to positively construct selfhood; however, consciousness alone is not sufficient.

For Sartre, the selfhood that one eventually develops has been shaped by prereflective experiences. Eventually, a reflective human may reject or affirm prereflective influences, but that awareness is not always comfortably experienced; it does not occur naturally simply because one is human. The influence of others is vital; the prereflective influence of others is foundational. As social animals, humans are continuously being shaped; that is, one’s sense of self is dynamically constructed as one grows increasingly reflective. Humans begin to shape themselves based on the stage set by prereflective influences that have first begun to form the idea of who they are. Human development, then, is contingent upon being with others. Indeed, as Sartre states, others are a “necessary condition for [one’s] being-for-[him/her]self.”7 Though self is an idea, a construct, it is situated in physical, tangible contexts. Therefore, others in the physical world shape us: “The Other holds a secret—the secret of what I am.”8 Over time, human consciousness begins to reflect the influence of others as humans develop a self: “The Other teaches [us] who [we are].”9

Sartre’s view requires the actual physical, material reciprocal interactions with others, such as the “look” and “touch.”10 In other words, even in our prereflective state, consciousness is being developed as a result of our ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Introduction

- Part 1. Burton and Identity

- Part 2. Burton and Authority

- Part 3. Burton and Aesthetics

- List of Contributors

- Index