- 300 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Growing Democracy in Japan by Brian Woodall in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Japanese History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Anti-Westminsterian Roots of Japan’s Parliamentary Cabinet System, 1868–1946

The cabinet, in a word, is a board of control chosen by the legislature, out of persons it trusts and knows, to rule the nation.

—Walter Bagehot, The English Constitution ([1867] 1925), 14

In England a party cabinet is headed by the leader of the party commanding the majority in the House of Commons; but not so under the imperial constitution of Japan. To insist on such a principle is to encroach on the sovereign power of the emperor.

—Prime Minister Terauchi Masatake, quoted in T. Iyenaga, “Parties and the Cabinet System in Japan” (1917), 382

INHOSPITABLE ROOTS

The modern cabinet system that was established in 1885 did not materialize out of thin air. In fact, it inherited organizational structures, institutions, and experienced administrators from the “Grand Council,” an administrative system that was originally imported from China during the eighth century and was resurrected as part of the Meiji Restoration, an institutional reconfiguration initiated in 1868. The Chinese characters that combine to form the Japanese term for “cabinet”—nai and kaku—translate to mean “inner palace.”1 From 1868 until 1898, Japan’s central state executive was dominated by a cabal composed of leaders from Satsuma and Chōshū, two feudal domains that played the protagonist’s role in bringing about the Restoration. When a schism in the Meiji government gave impetus to a “freedom and popular rights movement,” the Sat-Chō cabal responded by granting a constitution that vested sovereignty in a divine-right monarch and erected steep barriers to prevent popularly elected representatives from having meaningful influence on national policy. Although the Sat-Chō cabal went to great lengths to control all of the major executive organs, including the military branches, the “people’s parties” and elected members of Parliament managed to claw their way into the inner sanctum of policy-making. So it was that the era of “cabal cabinets” gave way to a brief period in which “party cabinets” wielded influence. When party government became synonymous with political corruption and pusillanimous diplomacy, technocratic government bureaucrats and military officers joined forces with the leaders of fascist-inspired groups in establishing a “new structure” of domestic institutions and a “new order” in East Asia. This ushered in an era of “techno-fascist cabinets.”

Japan’s current parliamentary cabinet system inherited important legacies from the authoritarian prewar order. In fact, the organizational genealogy of many of today’s cabinet-related agencies can be traced to organs established in prewar times. Just as prewar cabinets never played more than a subordinate executive role, postwar cabinets have not played the expected role of imparting strategic direction to government policy. For instance, the decision made by American occupation authorities to indirectly govern a defeated Japan through the existing civil bureaucracy perpetuated a state of affairs in which the primary purpose of cabinet meetings was to ratify decisions made by elite career civil servants. Likewise, the absence of a robust collective solidarity norm that undermines contemporary cabinets is the offspring of a system in which prewar ministers were individually responsible to a divine-right sovereign and were in no way responsible to Parliament. Then there is the human bridge embodied in the twenty-six prewar cabinet ministers—including five prime ministers—who held portfolios in postwar cabinets.2 To understand these legacies, it is necessary to examine the historical process through which an anti-Westminsterian prewar cabinet system evolved.

THE MEIJI RESTORATION

On July 8, 1853, Commodore Matthew C. Perry led a squadron of “black ships” (kurobune)—so known because two of the four American vessels were smoke-belching steam frigates—into Edo Bay. He brushed off attempts to get him to make his appeal at Deshima in faraway Kyūshū, as was required of foreign emissaries. Instead, Perry demanded to present a letter from President Millard Fillmore to the Japanese emperor proposing to open bilateral trade. Perry’s request was denied, and he departed peacefully and vowed to return the following year.

Despite the small size of Perry’s squadron, Japanese officials recognized that it packed sufficient firepower to outgun Edo’s meager shore defenses (Ravina 2004, 55). This created a quandary for Japan’s supreme political leader, the shōgun, who ruled the country from Edo Castle. In fact, well before Perry’s uninvited visit, nationalist thinkers had begun questioning the legitimacy of a shōgun who ruled while a divine-right emperor merely reigned from the Imperial Palace in Kyoto (Pyle 1996b, 51). In an unprecedented move, the shōgun’s chief adviser asked for written input from the local lords—known as daimyō—on how to respond to the American demands (ibid., 62–63). When Perry returned the following February—this time in command of a seven-ship flotilla—the shōgun’s agents meekly acquiesced and signed the Treaty of Peace and Amity (Nichibei Washin Jōyaku). By the terms of the treaty, an American “diplomatic agent”—a role performed by Townshend Harris—was permitted to reside in Japan. Harris negotiated the 1858 U.S.-Japan Treaty of Amity and Commerce, the first of a series of “unequal treaties” with the Western powers that imposed a semi-colonial status by denying tariff autonomy and granting extraterritoriality to Westerners in Japan (Gordon 2003, 50).

The arrival of Perry’s ships turned what had been a “chronic low-grade crisis into an acute, reactionary situation” (ibid., 46). When the domestic powder keg finally exploded in 1867, the shōgun was Tokugawa Yoshinobu, fifteenth in a family dynasty that had ruled Japan through relative peace for 264 years. In essence, the Tokugawa shōgunate governed through a system of “centralized feudalism,” whereby ruling power was based in Edo while some 250-odd daimyō enjoyed substantial autonomy in administering their regional domains (Craig 1961, 3). Some of these daimyō were blood relatives (shinpan daimyō) or hereditary vassals (fudai daimyō) of the Tokugawa. But certain “outside lords” (tozama daimyō) were never fully trusted—and for good reason, as we shall see—as they had to be forced to submit to Tokugawa domination yet were too powerful to be removed.

Thus, the shōgunate ensured that tozama daimyō governed domains far from Edo and that they and all daimyō spent alternate years in the shōgunal capital, while their wives and heirs remained there as hostages. This “alternate attendance” (sankin kōtai) system consumed up to half the time and revenue of the daimyō “in the purely ceremonial functions of attending the shōgun’s court and traveling in stately procession between Edo and their fiefs” (Vlastos 1990, 6). Some of the tozama daimyō—such as Mori of Chōshū, whose castle had to be relocated because the Tokugawa substantially reduced the area of domain—continued to harbor animosity toward the shōgunate two and a half centuries later (Hackett 1971, 6–7). By the time of Perry’s visit, certain powerful tozama daimyō were contravening shōgunal prohibitions by engaging in foreign trade, setting up Western-style factories, and building strong local militaries (Pyle 1996b, 70–71). It was difficult for the shōgunate to police and punish such acts of insubordination because of the distance of these domains from Edo. With Tokugawa influence waning, some tozama daimyō began pressing for the creation of a council of lords in Kyoto, in which the Tokugawa shōgun would be first among equals, to grant them greater voice in national politics.

If the tozama daimyō felt constrained by the shōgunate’s stifling controls, low-ranking samurai were incensed at a social order that placed them in perpetual subordination to superiors who “had been corrupted by inherited rank beyond the possibility of . . . redemption” (Smith 1988, 11). They were also outraged that a shōgunal official coerced the emperor into consenting to the inequitable Harris Treaty that invited “the threat of barbarian domination and debauchment” (ibid., 159). For the most part, these “men of spirit” (shishi) were angry young samurai who lived on modest incomes, if not in real poverty, and deeply resented the fact that they were denied access to important offices of government by a rigid hereditary system (ibid., 136, 139–40; Jansen 2002, 338). After Perry’s uncongenial visit, shishi emerged from domains across the country and converged upon Kyoto. When Tokugawa forces sought to squelch the mounting intrigue in the imperial capital, many of these young hotheads fled to Chōshū, where they were joined by a handful of refugee allies from the Imperial Court (Beasley 1995, 48). Although there was no specific unifying ideology, these firebrands shared a belief that action, not mere words, was necessary to destroy an incurably corrupt shōgunate, restore ruling power to the emperor, and cast out the Western barbarians. In retrospect, the temperament of these shishi is reflected in the violent ends they met. Indeed, seven of the ten leading figures in the defeat of the shōgunate and establishment of the new regime were assassinated, committed suicide, or were executed.3

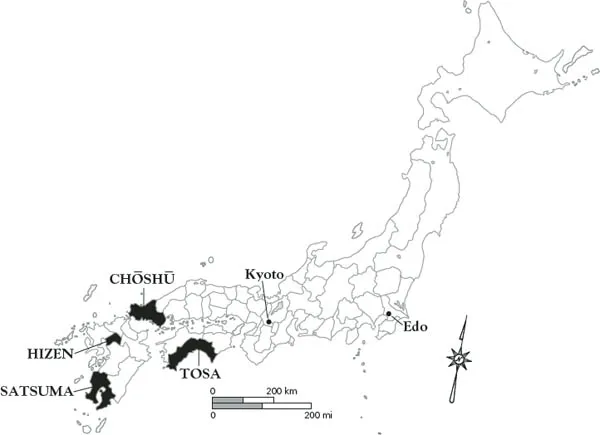

Figure 1.1. Major Outside Domains. Map by Dick Gilbreath, University of Kentucky cartography lab

The Tokugawa rulers attempted to turn back the insurrection through various reforms. In 1862, the shōgunate modified the alternate attendance system to require daimyō to reside in Edo only one hundred days every three years and permitted family hostages to leave. The ban on the construction of oceangoing vessels was lifted, and, in a move that had not occurred in two hundred years, the shōgun traveled to Kyoto to consult with the emperor (Pyle 1996b, 66–67; Duus 1998, 76). Meanwhile, the shōgunate retained a French mission to advise in military modernization, and considered adopting a Western-style cabinet system with functional ministries (Cullen 2003, 196). This was too late and too little. In 1863, loyalists convinced the emperor to order the shōgun to expel the Western barbarians, and a deadline of 25 June was agreed to, even though the shōgunate knew that it could not enforce this order (Gordon 2003, 55).

When the Edo authorities failed to act, Chōshū hotheads took matters into their own hands and fired on Western ships passing through the Strait of Shimonoseki, eliciting a retaliatory bombardment by British, Dutch, French, and American warships. Around the same time, Satsuma, another powerful tozama domain, was shelled by British warships for refusing to make reparations for the assassination of an English businessman by samurai retainers of its daimyō. In 1864, extremist samurai from Chōshū and elsewhere marched on Kyoto to rescue the emperor, but Tokugawa and Satsuma troops drove them out (Gordon 2003, 56). The shōgunate dispatched a punitive mission to Chōshū, which saw to it that the leaders of the failed coup were executed. In January 1866, officials from Tosa, another important tozama domain, brokered a secret alliance between Satsuma and Chōshū in the cause of toppling the shōgunate. When the shōgunate dispatched a second punitive mission to Chōshū in June, Satsuma and other domains refused to supply troops (ibid., 57).

So it was that the curtain came down on two and a half centuries of Pax Tokugawa. In November 1867, after coming to believe that he would remain first among peers in a governing council of daimyō, Shōgun Tokugawa Yoshinobu agreed to “return” power to the emperor and withdrew to his castle in Osaka. But leaders from Satsuma and Chōshū engineered the issuance on January 3, 1868, of an imperial rescript officially declaring the shōgunate defunct and “restoring” ruling power to the Emperor Meiji, then a fifteen-year-old boy. Yoshinobu responded by dispatching a sizable army to Kyoto to deliver a message protesting his ouster, but a small defensive force from Chōshū, Satsuma, and Tosa easily prevailed. After Edo Castle was bloodlessly surrendered to a combined Satsuma-Chōshū army in April 1868, the defeat of the Tokugawa shōgunate was complete, save for a few scattered pockets of resistance that held out for another year. The Boshin War was a small-scale civil war in which an undermanned “imperial” army soundly defeated forces loyal to Yoshinobu, who was sent into confinement. The conflict’s final battles were fought to suppress Enomoto Takeaki and his followers, the last remaining band of rebels, who had commandeered some of the shōgunate’s naval vessels and sailed off to Hokkaidō to carry on the fight. By the time Enomoto’s forces were finally defeated in July of 1869, the emperor had been relocated to Edo, now known as Tokyo or “eastern capital.” In the meantime, the powerful outside lords symbolically returned control of their domains to the emperor in 1871; soon, virtually all daimyō had followed suit and were appointed governors of their former fiefs, now known as “prefectures.”

Out of this foment emerged the Meiji Restoration (Meiji ishin), a dramatic reconfiguration of institutional and structural arrangements amid a “generation of sweeping and breathless change such as history had rarely seen” (Smith 1988, 134). Yet, in reality, an oligarchy composed largely of young ex-samurai primarily from Satsuma and Chōshū—with supporting roles played by similarly spirited men from Tosa and Hizen, another powerful tozama domain—replaced the Tokugawa shōgunate as the actual rulers of a new regime that continued to govern behind the façade of imperial rule. This marks the genesis of the era of “hanbatsu (domain clique) politics”—during which time a “Sat-Chō-To-Hi alliance” (Sat-Chō-To-Hi dōmei)—supposedly ruled the roost (Large 2009, 156). However, the real power brokers in this arrangement were oligarchs from Chōshū and Satsuma, who were at pains to establish institutions that enabled them to maintain an iron grip on political power and the distribution of policy benefits. From 1871 until 1898, this Sat-Chō cabal controlled all of the key positions in government, including the most coveted and powerful ministerial portfolios. This did not go unnoticed by leaders from Tosa and Hizen, a number of whom would soon leave their positions in government and become renegade agents of change.

Cabinet Forms and Structures

Japan’s first cabinets emerged three and a half years after the Meiji Restoration and were cobbled together out of preexisting organizational structures and staffed in large measure by members of the traditional administrative elite. Having vanquished the shōgunate and, at least on paper, returned ruling power to the emperor, the victorious insurrectionaries had to establish an administrative system through which to govern the country. To reinforce their “Restoration” message, they resurrected a long moribund governmental system fashioned after a model imported from T’ang China during the eighth century.4 Out of the Grand Council of State, as that administrative system was known, emerged what were, in effect, Japan’s first proto-cabinets. These proto-cabinets arose spontaneously within the group of relatively youthful officials appointed to serve as imperial councilors (sangi), whose membership bore testimony to Sat-Chō dominance. This oligarchic control continued even after the establishment of a modern cabinet system in 1885, and would persist for nearly a decade and a half thereafter.

Chinese Roots of Japan’s Cabinet System

China was the natural place for the Emperor Meiji’s distant predecessors to look for inspiration in designing administrative structures to facilitate centralized control over all of Japan. As Korean priests who appeared at the Japanese Court in A.D. 623 reported, “The Land of Great T’ang is an admirable country whose laws are complete and fixed. Constant communications should be kept up with it” (Asakawa 1903, 150, 253). Japan’s rulers dispatched numerous missions across the treacherous seas separating Japan from the Asian mainland (ibid., 148–150). Some Japanese emissaries remained in China for decades. In 649, the Japanese government enlisted several returnees from missions to T’ang China to advise in the design of governmental institutions (Varley 1974b, 27).5 Their input led to the creation of an administrative system based on a Department of Rites (Jingikan) and a Department of State (Dajōkan). The Department of Rites oversaw matters involving religious and court rituals, yet enjoyed little real power (Varley 1974a, 34). The Department of State—also known as the Grand Council—administered secular affairs. In theory, the council was under a leadership triumvirate consisting of a grand minister of state (dajōdaijin), minister of the left (sadaijin), and minister of the right (udaijin). However, in practice the grand minister had no specific duties other than to advise the emperor, and the post generally remained vacant. The council was divided into eight functional ministries: Central Administration, Ceremonial, Civil Affairs, People’s Affairs, Military Affairs, Justice, Finance, and Imperial Household (Varley 1974a, 34).6

Over time, the Grand Council’s administrative powers dissipated. By the mid-ninth century, the Fujiwara family, through its monopolization of the positions of regent (sesshō) and chief councilor (kanpaku), was able to effectively manipulate a succession of emperors. Wit...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Abbreviations and Japanese Terms

- Note on Conventions

- Introduction

- 1. The Anti-Westminsterian Roots of Japan’s Parliamentary Cabinet System, 1868–1946

- 2. Comprador Cabinets and Democracy by the Sword, 1946–1955

- 3. Corporatist Cabinets and the Emergence of the “1955 System,” 1955–1972

- 4. Confederate Cabinets and the Demise of the “1955 System,” 1972–1993

- 5. Disjoined Cabinets—Act I: Coalition Governments and the Lost Decades, 1993–2006

- 6. Disjoined Cabinets—Act II: Twisted Diets and Lost Leadership Opportunity, 2006–2013

- Conclusion

- Acknowledgments

- Appendix A. Japanese Cabinets and Cabinet Ministers Database

- Appendix B. Ministers’ Parliamentary and Social Attributes

- Appendix C. Ministerial Hierarchy

- Notes

- Selected References

- Index