eBook - ePub

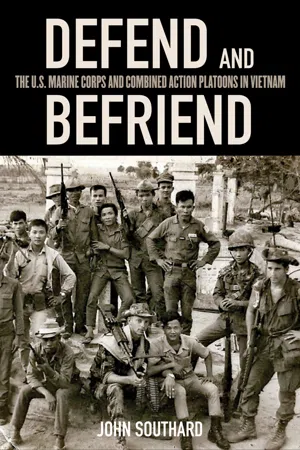

Defend and Befriend

The U.S. Marine Corps and Combined Action Platoons in Vietnam

- 232 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Defend and Befriend by John Southard in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military & Maritime History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

The Evolution of Combined Action Platoons

We had found the key to our main problem—how to fight the war. The struggle was in the rice paddies, in and among the people, not passing through, but living among them, night and day, sharing their victories and defeats, suffering with them if need be, and joining them in steps toward a better life long overdue.

—Lewis Walt

The practice of embedding U.S. Marines among an indigenous population did not originate in Vietnam. The World War I–era Marine Corps first combined the military and political components of a counterinsurgency in Haiti, the Dominican Republic, and Nicaragua. In all three engagements, Marines organized and commanded small units of indigenous military personnel. Alongside the local forces, the Marines conducted patrols against insurgents while providing aid to civilians. The Marines’ experiences in these conflicts spawned doctrinal developments in the Marine Corps during the early 1930s that spoke to counterinsurgency and counterguerrilla warfare. However, the later wars against the empire of Japan and the Communists in Korea rendered counterinsurgency doctrine and training obsolete. By the start of the Vietnam War, the Marine Corps had dedicated itself to mirroring the fundamental strategies and tactics of World War II and the Korean War, which had brought the institution military success and the American public’s admiration and attention. From the 1930s through the early 1960s, the Marine Corps had developed into America’s finest amphibious assault force. In the decades preceding Vietnam, the Marine Corps had paid little attention to the concept of counterinsurgency. Yet in Vietnam, Marine commanders such as Lewis Walt and Victor Krulak quickly realized that the geographic, political, and military landscape of the war was incongruent with the decades of conventional training they had both received and helped to advance. The program emerged spontaneously as part of a larger strategic framework in which Marine commanders sought to gain military and political leverage among the indigenous people in I Corps.

Learning from its experiences in the Caribbean, the Corps formalized a small-wars doctrine in the 1930s.1 The development of the Fleet Marine Force in 1933, confirming the Marine Corps as an amphibious landing force tied to the U.S. Navy, sparked much controversy within the service over the development of its small-wars doctrine. Many Marines, including the assistant commandant, Lt. Gen. John Russell, envisioned a future Corps prepared for a large conventional confrontation with the world’s major powers. Focusing on small wars in peripheral regions would undermine the development and ultimate success of the Fleet Marine Force. Yet the Marine officers advocating the development of small-wars doctrine pushed hard enough to get a manual published in 1935, ultimately titled the Small Wars Manual five years later.2 The 1940 version of the manual defines small wars as “operations undertaken under executive authority, wherein military force is combined with diplomatic pressure in the internal or external affairs of another state whose government is unstable, inadequate, or unsatisfactory for the preservation of life and of such interests as are determined by the foreign policy of our Nation.”3 The manual included detailed descriptions of the military and political components of a small war, much of it based on the Marines’ experiences in Latin America. Throughout the late 1930s, Marine schools gradually increased the amount of time allotted for small-war instruction, but lessons never surpassed 10 percent of the overall academic curriculum.

In the two decades following the publication of the Small Wars Manual, pacification and counterinsurgency fell by the wayside. In the years preceding World War II, the Marine Corps collaborated with the navy in perfecting the doctrine and practice of the Fleet Marine Force. The Marine Corps hammered its officers with schooling and joint exercises with the navy, learning and practicing the art of launching amphibious assaults to capture forward bases. From 1932 to 1941, Marine officers tackled scenarios in the classroom that tested their ability to devise solutions for assaulting enemy beachheads. “Fleet landing exercises” every winter off the coast of San Diego gave Marines and sailors the opportunity to rehearse the developing Fleet Marine Force doctrine.4 In World War II, the aggressive, offensive-minded approach to waging a successful war in the Pacific justified the continuance of the Fleet Marine Force concept. The triumphant Marine amphibious assaults against a well-trained Japanese military bolstered the already beaming pride the Corps had in its conventional abilities. The Korean War further boosted the prestige of the Marine Corps. The successful amphibious assault at Inchon in September 1950 and the subsequent annihilation of Chinese forces during the First Marine Division’s retreat from the Chosin Reservoir at year’s end upheld the Marines’ insistence on enhancing the Fleet Marine Force concept. After the Korean War, the Marine Corps continued the development of the Fleet Marine Force, despite President Dwight Eisenhower’s “New Look,” which emphasized strategic air power and the threat of massive retaliation with nuclear weapons. Facing massive cuts in size and strength in the Eisenhower administration, the Marine Corps attempted to usher in vertical assault to its amphibious doctrine to keep the military branch afloat in the Department of Defense. The advent of helicopters in the Fleet Marine Force of the 1950s also made counterinsurgency seem obsolete. As Marine Corps schooling in the late 1950s opined, “The civil population must be excluded, where possible, from close contact with our forces.”5

In 1961, President John F. Kennedy began to replace Ike’s “New Look” with “Flexible Response,” a strategy centered on preparing the U.S. military to fight any type of war, small or large, conventional or unconventional, anywhere in the world. Kennedy’s bid to spread the importance of counterinsurgency across all services fell mostly on deaf ears in the Corps. Marine Corps schools implemented counterinsurgency instruction in their curricula, but the Marines learned little about civil affairs, civic action, and population control.6 In the early 1960s, instruction on counterinsurgency lagged far behind amphibious assault doctrine and division-sized exercises that resembled World War II landings in the Pacific.7 The commandant of the Corps during the Kennedy administration, Gen. David Shoup, frequently expressed his reluctance to develop counterinsurgency doctrine. Shoup, who became a strong critic of American intervention in Vietnam, deemed counterinsurgency unrealistic and believed, in any case, that it should fall under the auspices of the army, not the amphibious assault-minded Marine Corps.8 Gen. Wallace Greene, Shoup’s successor as commandant, communicated to Congress in 1965 that “the Marine Corps is in the best condition of readiness that I have seen in my thirty-five years of naval service.”9 Greene’s analysis of the readiness of the Marine Corps was, in a sense, correct. The Marine Corps was indeed ready to fight a war, but not the type of conflict that erupted in Vietnam. The Marines who landed at Da Nang in March 1965 were products of a Corps that had an ardent affinity for amphibious and vertical assaults, rendering the concept of counterinsurgency insignificant in the minds of some of the highest-ranking and influential Marines. Marine commanders in South Vietnam had to transform a large portion of their conventional force into an unconventional, versatile group that could counter guerrilla activity. Yet when the Marines first arrived for combat purposes in South Vietnam, decades had passed since the Marine Corps had given any serious attention to counterinsurgency.

One of the few exceptions to the Marine Corps’ infatuation with conventional war appeared in the 1962 publication of Field Manual (FM)-21, Operations against Guerrilla Forces. This field manual acknowledged the successful counterguerrilla campaigns of the U.S. Army in the Philippines at the turn of the century as well as the later British counterinsurgency in Malaya. FM-21 stressed the need in counterguerrilla operations for a temporary patrol base distant from the parent bases. The manual also noted that success in a guerrilla environment depended heavily upon small-unit patrols. Some criteria for a successful counterguerrilla operation in the manual differed from the ultimate mission of CAPs in Vietnam. For example, the manual lays out plans of attack for assaulting guerrilla homes and camps, but CAPs, charged with the primary goal of protecting the villages, did not have as objectives finding and then destroying enemy base camps. Moreover, according to the manual, the best sources of intelligence are maps, recent patrols, photographs, and ground and aerial reconnaissance. Gaining intelligence via interaction with local civilians is conspicuously absent from the intelligence section. Successful counterguerrilla operations, according to the manual, did not entail staying in the villages. Rather, one of the methods for reducing villagers’ contact with the enemy was to evacuate or relocate civilians from enemy hotbeds to safer locations, because “areas cleared of civilians provide better areas for tactical operations.” The manual does mention the importance of amicable U.S.-civilian relationships, but it also justifies civilian relocation, arguing that “total or partial evacuation of a given area may be undertaken for the security of the population for imperative military reasons.”10 Operations against Guerrilla Forces was a marked deviation from the primary mission of amphibious assaults that so aptly characterized Marine Corps training and doctrine before the Vietnam War. In the same year as the release of FM-21, a U.S. Marine Corps publication found that the service was foremost prepared to commence amphibious assaults.11 However, storming beachheads in South Vietnam would not earn the respect or win the allegiance of civilians isolated in rural areas.

In Vietnam, the program did not emerge as a direct by-product of Marine Corps doctrine. Instead, the concept of CAPs emerged and progressed in an evolutionary manner, as Marine commanders in 1965 began to realize that the United States could not win the war by relying on its overwhelming firepower and superior technology. When the Marines arrived in Da Nang, they fell under the command of U.S. Army general William Westmoreland, who as commander of MACV held operational control over all American forces in South Vietnam. Just as the Marines in the years leading up to 1965 were obsessed with continuing their amphibious assault doctrine, the army possessed an institutional devotion to conventional war in the form of attrition.12 Backed by Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, Westmoreland employed a strategy whereby American forces would use their mobility, firepower, and technology to attain high enemy body counts. With the larger NVA and VC main force units roaming the countryside, Westmoreland saw attrition as the only conceivable choice to win the war. He wanted the Marines to leave the enclaves they had established along the coast of I Corps. Westmoreland and his MACV staff described the enclave strategy as “an inglorious, static use of U.S. forces in overpopulated areas with little chance of direct or immediate impact on the outcome of events.”13 Moreover, Westmoreland feared enclaves would allow the NVA to infiltrate the Central Highlands, rendering the area impenetrable for U.S. forces.

Leading the III Marine Amphibious Force in Vietnam from June 1965 until June 1967, Lt. Gen. Lewis Walt disagreed with Westmoreland’s strategy. During his two years as commander of the U.S. Marine force in I Corps, Walt pursued a strategy of protecting the rural population within the enclaves the Marines had established. Walt’s inclusion of the Vietnamese people in his strategic blueprint may come as a surprise to some. After all, Walt, who by 1965 had served in the Marine Corps for nearly thirty years, was inextricably connected with a service that took great pride in its amphibious assault capabilities. After briefly serving in the Colorado National Guard, Walt had joined the Marine Corps in 1936 as a second lieutenant. By the fall of 1942, after his service with the First Marine Raider Battalion on the Solomon Islands and the Fifth Marines on Guadalcanal, Walt had been promoted to major. He went on to lead Marines at Cape Gloucester and Peleliu, ultimately returning to the United States in November 1944, having earned the Silver Star and two Navy Crosses for his participation in the Pacific. Walt commanded the Fifth Marine Regiment in the Korean War and later accepted positions in Quantico, Virginia, as an educator of Marine officers. Just before landing the job as IIIMAF commander, Walt had directed the Marine Corps Landing Force Development Center.

While Walt’s accomplishments in the 1940s and 1950s certainly bolstered his stature as a U.S. Marine officer, they do not shed light on why he sought to protect the rural population of I Corps and in turn become one of the chief architects of the Combined Action Program. Indeed, counterguerrilla and counterinsurgency operations seldom occurred in the Pacific theater of World War II or in the Korean War. More than any other era in his illustrious career, Walt’s pre–World War II service provided the future IIIMAF commander with a general knowledge of “small wars” and the importance of aiding the civilian population. In 1936, as a newly commissioned junior officer, Walt attended the Basic School in Philadelphia. In the 1920s and 1930s, the school conducted classes on the “small-war” experiences of the Marine Corps in Haiti, the Dominican Republic, and Nicaragua. Capt. Lewis “Chesty” Puller was the primary instructor of Walt’s group of junior officers.14 Puller used the Small Wars Manual as a general text, supplementing it with his personal wartime experiences in Haiti and Nicaragua. His recollections taught the junior officers the values of living off the land and engaging with the indigenous population in a productive way. According to one of Puller’s biographers, Walt “absorbed every word” that “Chesty” said.15

When Walt took control of IIIMAF in the spring of 1965, he admitted that the Marines had many strategic challenges ahead of them in I Corps. Walt faced the grim reality that the war in Vietnam would not feature many of the amphibious assaults that had symbolized the Marine Corps and its doctrine in the previous decades. Gradually, as the Marines opened three separate enclaves in I Corps during 1965, spreading from Thua Thien province to Quang Ngai province, Walt recognized, “It was a new kind of war we were in, where concern for the people was as essential to the battle as guns or ammunition, where restraint was as necessary as food or water.”16 From the spring of 1965 until their departure six years later, the Marines created their own way of fighting the war in Vietnam. Although adhering in part to MACV’s attrition-based strategy, the Marines exuded an unmatched dedication to securing and controlling the rural population.

Engagement in civic action was vital for creating amicable relations between the Americans and the Vietnamese. Early civic action in I Corps usually consisted of infrequent medical aid from corpsmen along with the distribution of C rations and soap to civilians. Throughout South Vietnam, government agencies and nongovernment organizations (NGOs) that provided supplies for civic action worked independently of each other. The result was disorganization and a time-consuming bureaucratic maze through which supplies were channeled before reaching their destination. Frequently, agencies failed to communicate with each other, resulting in lost supplies. Poor coordination also resulted in inequities: an abundance of supplies might land in one rural area while other villages received none.

In 1965, Walt amalgamated the multiple civic action agencies into the Joint Coordinating Council (JCC), a group of military and civilian representatives who collectively managed and organized the pacification effort in I Corps. The JCC determined requirements for agencies aiding Vietnamese civilians in I Corps and recommended specific procedures to make the multiagency process more efficient. Originally consisting of seven members, including representatives from IIIMAF, the MACV, the U.S. Operations Mission to Vietnam (USOM), and the Joint U.S. Public Affairs Office (JUSPAO), the JCC formed committees in special areas of interest for pacification and civic action such as public health, education, logistics, and finance. The JCC remained mindful of Saigon’s instructions for the overall pacification effort in South Vietnam, consistently molding its overall mission according to the RVN’s plans for rural development.

Also beginning in 1965, Walt oversaw various Marine programs to help pacify villages within the enclaves. Before the Marines’ arrival in I Corps in 1965, the VC had frequented villages to enforce rice taxes during harvest season. According to Walt, the rice demands from the VC varie...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Maps

- Preface

- Abbreviations and Acronyms

- Introduction

- 1. The Evolution of Combined Action Platoons

- 2. Combined Action Platoons, Green Berets, and Mobile Advisory Teams

- 3. Becoming a Combined Action Platoon Marine

- 4. Life in a Combined Action Platoon

- 5. Popular Forces in Combined Action Platoons

- 6. The Combined Action Program and U.S. Military Strategy in Vietnam

- Conclusion

- Acknowledgments

- Appendix: Historiographical Essay

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index