![]()

1

Pioneer Canals and Republican Improvements

Like so much in American history, the first canals were derivative from those of Europe. The Dutch, the French, and, especially in the latter half of the eighteenth century, the English carried the technology of canal building forward from its ancient origins. The Dutch developed a canal-integrated economy; the French completed the great Languedoc Canal (Canal du Midi), 148 miles long, in 1681; and the English midlands were crisscrossed by a rapidly expanding network of narrow canals from Regents Park in London north to Scotland. Many of the English canals were being built just as the Canal Era opened in the United States.1

In America the Canal Era emerged out of the transfer of European technology, stimulated by the ideal of a water-connected society in a garden environment.2 English examples in canal building were followed most frequently, and the English engineers William Weston and Benjamin Latrobe did the surveys for most of the pioneer canals in the 1790s. Weston brought the Troughton Y level, a spirit level attached to a telescope, which was probably the first leveling instrument in America.3 American engineers such as Loammi Baldwin, Jr., Canvass White, William Strickland, and Robert Mills, who lacked formal training, tramped the English canals and above all sought English experience in their crucial quest for a workable underwater cement.

The engineers who struggled to build the first American canals faced the most elementary yet trouble-plagued problems: how to take an accurate level, often with only the equipment of a country surveyor; how to dig a canal channel and remove the earth most efficiently; how best to cut through tree roots; how to use blasting powder to remove embedded rock; how to keep canal banks from leaking by “puddling”; how to mix a permanent underwater cement, to design lock gates, to make valves for the gradual release of water, and to create locks and gates that could be operated easily by hand power.

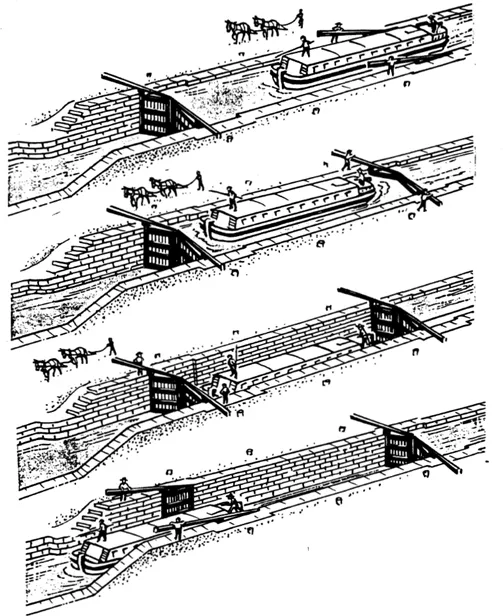

Operation of a canal lock. To lower a boat the lock is filled by opening the wickets in the upper gates. After the water level rises, the upper gates are swung open and the boat enters the lock. The wickets in the lower gates are then opened to drain the lock, lowering the boat as the water falls to the level of the canal below. When the lower level is reached, the lower gates are opened and the boat proceeds downstream. The procedure is reversed to lift boats to higher levels as they move upstream. Drawings from F. Charles Petrillo, Anthracite and Slackwater: The North Branch Canal, 1828-1901 (Easton, Pa., Center for Canal History and Technology, 1986). Reprinted with permission.

The first canals of the 1790s were tiny in size, painfully slow in construction, and financed by companies that were always short of funds. Yet these companies were led by the landed or commercial gentry of the time, with names distinguished for political leadership or social standing. These early canal builders were imbued with a spirit of improvement that has often been obscured by their political contributions in creating a new nation. Although the canals they built were short waterways and their companies were small, they were attempting to achieve the same republican ends that they pursued in better-known positions of public service.4

River improvements in the 1790s and early 1800s were too numerous to trace, but several short canals stand out in the pioneer experiences of canal building in America. The Schuylkill and Susquehanna Canal in Pennsylvania and the Potomac Canal in Virginia started toward a common destination in the Ohio Valley. Navigation of the Susquehanna River was improved by the Conewago and Susquehanna canals. Along the Atlantic coast, the Dismal Swamp Canal connected Chesapeake Bay to Albermarle Sound. In the northeastern states, the Western Inland Lock Navigation Company built important canals in the Mohawk Valley; and in Massachusetts, the Middlesex Canal reached from Boston up to the Merrimack River and New Hampshire. Far to the south the Santee and Cooper Canal brought the trade of the upland rivers to Charleston. Not only did canal ventures in Pennsylvania and Virginia share a common goal in the improvement of water transportation to the Ohio Valley, but their early engineering experiences contributed to the building of other pioneer canals in the 1790s.5

In Pennsylvania, long before the Revolution, a group of Philadelphians including Thomas Gilpin, David Rittenhouse, Benjamin Franklin, William Smith, and Thomas Mifflin began to make plans for water improvements from Philadelphia to the Susquehanna Valley. They developed what Darwin H. Stapleton has called the “Philadelphia plan,” which considered three routes by which Philadelphia might gain the trade of the Susquehanna Valley, one by a canal across the Delmarva Peninsula south of Philadelphia, one by a road from the Susquehanna to a river port near Philadelphia, and a third from the Schuylkill River to the Susquehanna by a canal along their tributaries, the Tulpehocken and the Swatara rivers. The last of these three routes became the project for the Schuylkill and Susquehanna Canal.6

The building of this canal became the goal of the Society for the Improvement of Roads and Inland Navigation in 1789, organized by Robert Morris, Rittenhouse, Smith, and the Philadelphia land speculator John Nicholson. The society’s president was Morris, who signed its memorial to the Pennsylvania Assembly, marking out a water route to the interior. The canal would go up the Schuylkill and Tulpehocken rivers and cross the summit level near Lebanon by a canal, to reach the westward-flowing Quitapahilla River and the Swatara, which was tributary to the Susquehanna.

In response to the society’s proposal and the Morris memorial, the Pennsylvania legislature incorporated the Schuylkill and Susquehanna Navigation Company in 1791 to build the Schuylkill and Susquehanna Canal and improve the navigation of the Schuylkill River. To connect this canal to Philadelphia, the Delaware and Schuylkill Navigation Company was chartered to build another canal to run from Norristown on the Schuylkill for seventeen miles to the Delaware River near Philadelphia. Robert Morris was president of both companies.

The Inland Navigation Society and the Morris memorial projected a route to continue west through the Susquehanna Valley to the Juniata River and up that valley to Poplar Run. There a short mountainous portage was necessary to reach the Conemaugh, the Kiskiminitas, and the Allegheny rivers, which led finally to Pittsburgh on the Ohio River. The total distance of this long water route was calculated to be 426 miles, and Morris and his associates concluded that it would allow goods to be carried more cheaply from Philadelphia to the Ohio River than from any other Atlantic port. This great route, Governor Mifflin told the legislature in 1790, was “a natural avenue from the shores of the Atlantic to the vast regions of the western territory,” connecting “the extreme members of the union,” and offering rewards beyond imagination.7

Almost desperate for professional engineering skill, the Schuylkill and Susquehanna Canal Company brought the English engineer William Weston to supervise construction on the Schuylkill and Susquehanna Canal. Weston was probably the son of Samuel Weston, an experienced English canal engineer, and he was recommended by William Jessop, who was then the leading engineer in England. William Weston had trained under James Brindley and had worked on canals in Ireland and central England. He was offered the then stunning stipend of £800 a year to work for the company for five years. When he arrived in Pennsylvania in 1793, he found more than six hundred men at work at Norristown and on the summit level on the canal between Lebanon and Myerstown.

Weston worked for about two years, hired laborers, and even made bricks for the locks. George Washington, a close friend of Robert Morris, made several trips out from the national capital at Philadelphia and on his third visit could examine the four brick locks built by Weston on the descent from the summit along the Tulpehocken River. But the best the company could do was to make about fifteen miles of canal east of Lebanon, spending $440,000, before funds ran out.8 Nothing was done by the other Schuylkill company, and it would be twenty-seven years before work could be resumed on this waterway with the construction of the Union Canal to be built by a new company that would combine the two short Pennsylvania projects of the 1790s into a larger venture.

Meanwhile, Robert Fulton advised Governor Mifflin in 1796 from England (where Fulton was studying painting with Benjamin West) on the utility for Pennsylvania of his new system of canal navigation, which “totally explodes the old practice,” would cost half as much, and could be built “through the most mountainous country.” He wrote to the governor that by his system a “Ton of Grain or other material, may be conveyed from Fort Pit or any other point distant 3 or 400 miles to Phila. for 21 shillings.” This was the year Fulton published his Treatise on the Improvement of Canal Navigation, and he recommended not only small boats of light tonnage but inclined planes for mountainous regions and what he called “double inclined planes” for crossing a valley without locks or aqueducts. Fulton had been born in Lancaster County in Pennsylvania, and Benjamin West added his endorsement to Fulton’s “motives of attachment to his country,” assuring Governor Mifflin that this was a “system . . . not to be contradicted.”9 But Fulton’s system would never be attempted, although may have influenced the planes of the railway segments of later Pennsylvania canal routes.

If little progress could be made on the Schuylkill-Susquehanna route to the West, the short “portage canal” at the Great Falls on the lower Susquehanna, completed in 1797, became the first working canal in Pennsylvania. The Susquehanna River rose in New York and was navigable down to the Conewago Falls and rapids, which began the last fifty miles of shallow passage and rough water before the river reached the Chesapeake at Port Deposit in Maryland. Rafts brought lumber from the timber stands on the upper branches of this great river, and long, narrow Durham boats brought wheat and other goods down the river. In 1790, 150,000 bushels of wheat came to the village of Middleton near Conewago Falls, and its mills turned the wheat into flour for shipment overland by wagon to Philadelphia. Only for a short period in the spring did high water allow safe navigation over and below the falls.

The improvement of the lower Susquehanna, combined with a canal across the Delmarva Peninsula, was part of the “Philadelphia plan.” In 1793 the Conewago Canal Company, whose proprietors included Robert Morris, David Rittenhouse, and William Smith, contracted with the Pennsylvania legislature to improve the navigation between Wright’s Ferry (Columbia) and the mouth of the Swatara River and to build a one-mile canal around Conewago Falls. The canal was to be forty feet wide and four feet deep and have at least two locks.10 Weston contributed his knowledge to the project, and in four years the canal was finished. Although it enabled passage of the major obstruction on the lower Susquehanna, James W. Livingood has found that the Conewago Canal had little effect on river navigation.11 The development of the “ark” in 1795, which could run the falls, allowed such craft to avoid the canal, and the continuing difficulties on the lower Susquehanna limited traffic.

The little Conewago Canal was only a part of the long and complex rivalry between Philadelphia and Baltimore for the Susquehanna trade. To obtain the right to construct the Chesapeake and Delaware Canal, Pennsylvania agreed in 1801 to declare the Susquehanna a public highway so the river could be improved. That year a Baltimore company, the Proprietors of the Susquehanna Canal, began work on a canal from the Pennsylvania-Maryland boundary to tidewater.12 Weston was unavailable because he was busy in New York and soon returned to England. The company turned to Benjamin Latrobe, who arrived in 1796 from England, where he had added to his knowledge of canal engineering on the Rye Harbor Improvement and the Basingbroke Canal. Beginning on the Susquehanna Canal in 1801, Latrobe created a straight channel thirty feet wide and three feet deep running for nine miles on the most difficult stretch of the river in Maryland. It had nine locks, which were a hundred feet long and twelve feet wide, and was finished in 1802.

But even this improvement was not profitable. The canal was too narrow for the larger craft coming down the Susquehanna, its use for turning mills increased the current and caused it to silt up, and the boatmen shunned its tolls. Moreover, it was nearly impossible to ascend the lower Susquehanna, “almost the whole of which,” wrote Latrobe in 1808, “is a tremendous rapid from Columbia to the tide.” Even with the Susquehanna Canal in operation, goods coming inland to the Susquehanna Valley were brought by wagon from Philadelphia to enter the river at Columbia. Although Latrobe did improve some rivers in Pennsylvania, the state was so anxious to protect the trade over the Philadelphia and Lancaster Turnpike that it refused to cooperate with Maryland in improving the river above Maryland’s Susquehanna Canal. The canal was sold in 1817 at a loss to the proprietors.13

At the same time, Latrobe began work on the Chesapeake and Delaware Canal, which was tied to the lower Susquehanna improvements and begun by a company chartered in Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Delaware. He began work on this project to connect the Chesapeake and Delaware bays in 1803 and continued until funds were exhausted in 1805 and work stopped. On this canal he trained two future canal engineers, William Strickland and Robert Mills.

While Pennsylvanians sought to improve the Schuylkill and Susquehanna routes to the Ohio Valley, Virginians sought to improve the Potomac route to the West, believing it superior to any other. The guiding spirit in Virginia’s effort was George Washington, who, after the Revolutionary War, turned his attention to canals. He made a tour of the waterways of eastern New York in 1783 and the next year undertook a great circular expedition up the Potomac, across the mountains to the Ohio River and Lake Erie, and back by the Kanawha and James rivers. His interest in the improvement of the Potomac had grown following his expedition to Fort Dusquesne in 1784, and his belief in canals was strengthened by his long experience as a surveyor.

When the Potomac Company was organized in 1785 to improve the Potomac navigation, Washington became its president. He believed such improvements would prove profitable to his land speculations, would be critical to the interests of his state of Virginia, and would help to preserve the American Union. Washington worried that western settlers would become commercially dependent upon the British and the Spanish “at the flanks and rear” of the United States. On his return from his long western journey in 1784, he wrote in his diary, “The Western Settlers—from my own observation—stand as it were upon a pivet—the touch of a feather would almost incline them any way.” A few days later he wrote almost the same words in a letter to Virginia’s governor, Benjamin Harrison.14

Washington estimated that the improvement of sixty miles of Potomac River navigation from Georgetown to Harpers Ferry could ultimately replace two hundred miles of land travel to the Ohio River. This could be done by improving the Potomac, adding a portage road from the Cumberland to the Monongahela River, and following the Monongahela to the Ohio. In a larger scheme he wished to turn the trade of the interior to the Potomac and his native Virginia, rather than allowing it to be drawn to the Mohawk Valley, the Hudson River, and New York. Since the Potomac is in Maryland, his efforts required the cooperation of that state, which he achieved in the Mount Vernon Compact of 1785, in spite of the resistance of Baltimore merchants.

Both James Madison and Thomas Jefferson supported the Potomac Company. Madison saw to the company’s interests in the Virginia legislature. Jefferson wrote to Washington in 1784 that the Potomac offered the shortest route to the “Western world.” In the “rivalship between the Hudson and Patowmac” he found the Potomac route 730 miles nearer from the Ohio River to Alexandria than to New York. “Nature then has declared in favour of the Potowmack,” he added, “and . . . it behoves [sic] us then to open our doors to it.”15

On the Potomac River there were five rapids or falls to be passed. Ten miles above Georgetown the Potomac Company built a canal with five locks around the largest obstruction, the Great Falls. James Rumsey, the chief engineer, was really a surveyor-mechanic, better known for his later attempts at steam navigation. William Weston came to the Great Falls works in 1795 and gave his advice. Washington continued to draw upon Weston by letters, and Weston returned briefly in 1796. Labor was supplied by free, indentured, and slave workers. Stock subscriptions given by merchants and planters from Alexandria and Georgetown were paid on a “pledge now—pay later” basis, and land speculations such as those of Richard Henry Lee and James Madison at Great Falls became enmeshed with canal stock pledges, to the detriment of the latter. Only an additional stock subscription by the Maryland legislature allowed the company to open the locks at Great Falls in 1802. Through them passed the little boats that entered the Potomac at Lock’s Cove, from which they were poled to Georgetown, Washington, or Alexandria.

By then the company had abandoned its plans for connections to the Ohio and limited its work to the improvement of the Potomac. But traffic on the Potomac was limited by lack of the anticipated settlement upriver and by changes in the European market so that by 1822 the company had spent $729,387 and had debts of $175,886.16 Still, the Potomac Company’s improvements served the Potomac trade and kept alive the ultimate goal of a canal to the Ohio River. Its faltering finances demonstrated the need for the national aid that would make possible its successor, the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal, which would pass beside the Potomac to Harpers Ferry by 1830.

In 1785, the year the Potomac Company was chartered, George Washington also sponsored the James River Company farther south in Virginia. Under the active management of Edmund Randolph, this company built a seven-mile canal from Richmond to the falls at Westham, which began to operate in 1795. And to the southwest, the Dismal Swamp Canal was built to connect Chesapeake Bay and the Pasquotank River, which led to Albermarle Sound off North Carolina. This waterway, opened in 1794 to small boats and enlarged in 1807 to take six-foot-wid...