eBook - ePub

Order in Chaos

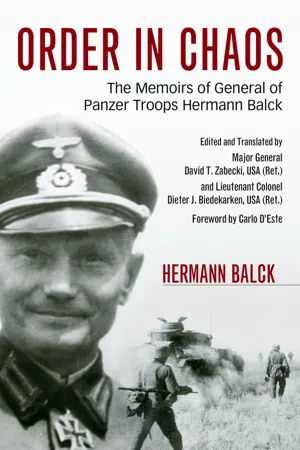

The Memoirs of General of Panzer Troops Hermann Balck

- 578 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Order in Chaos

The Memoirs of General of Panzer Troops Hermann Balck

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Order in Chaos by Hermann Balck, David T. Zabecki,Dieter J. Biedekarken in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

The University Press of KentuckyYear

2015Print ISBN

9780813174037, 9780813161266eBook ISBN

97808131612801

1914

War Breaks Out

Much has been written about the reasons war broke out in 1914, and most of that based on the politics of the day. Much of what has been written is not very deep. The German-English differences were fundamental. In a letter to my father, the German crown prince wrote: “I am concerned with the ever increasing contrast between Germany and England. This concern increased when in conversation with King Edward VII,1 who was always especially friendly to me, he openly expressed to me on several occasions that the differences had to be overcome one way or another. England would not allow the unilateral economic superiority of Germany for any length of time.”

The fact that tsarist Russia was pushing for war with Germany and consciously drove toward it has been clearly proven by the publication of documents and files by the later Bolshevik government. According to Alexander Isvolsky, Russian foreign minister from 1906–1910 and ambassador to Paris from 1910–1917, “I am the father of this war.” And according to Sergey Sasanov, Russian foreign minister from 1910–1916, “The peace-loving German Kaiser will ensure that we can choose the time for war to break out.”

But what was the reason? Russia was a colonial land with vast estates in the hands of the landed barons, “the Boyars,” who controlled a class of peasants whose lot only slightly improved after they had been freed from serfdom. Herein lay the seed for the coming revolution. After the unfortunate Russo-Japanese War of 1904–1905 one of the most important personalities of modern Russian history emerged as prime minister, Pyotr Stolypin. He concentrated his efforts on the right issue, the unjust land distribution. The Stolypin Reform created the independent farmers, the Kulaks. This was a large-scale reform and was very successful.

Naturally the land could only be taken from the landed barons. Their reaction came soon enough. When in 1911 Stolypin was shot and killed in the theater in Kiev, allegedly by a social revolutionary, the reform that had begun with such promise came to an end. That he had been on the right track was proven by the fact that no other social group was persecuted more by the Bolsheviks than the Kulaks.

As so often when an incompetent government is facing internal problems it cannot resolve, it seeks to overcome domestic failures through foreign policy successes. The decision to go to war had been made. Only Germany, which just recently had helped Russia by remaining neutral during Russia’s war with Japan, was an immediately convenient adversary. “The road to Constantinople goes through Berlin.” The German foreign ministry had continuously maintained that Russia would very likely seek friendlier relations. The Kaiser accurately countered, “The Slavs are now siding with England, by whom they were beaten in the Far East.”

Germany, which could not make up its mind whether to side with England or Russia, was caught in between. Since World War I, Germans, as usual, have made Pan-Germanism partly responsible for the war. This fails to recognize the forces of Pan-Slavism in Russia, irredentism in Italy, revanchism in France, jingoism in England, and other “isms” elsewhere. It was a phenomenon of Europe’s imperial age that simultaneously created the same stupidities all over Europe.

As for Germany’s often blamed naval policies, they probably would have brought England to the negotiation table in the end. It is an irony that the German-English Colonial Treaty, which would have brought a great reduction of tensions and a resolution of the differences, was ready to be signed at the beginning of August 1914. “German-English relations were never better than in the summer of 1914,” as Winston Churchill said in the House of Commons. And as Paul Cambon, France’s ambassador to London, expressed among friends in May of 1914, “We have lost this game.”

It would be interesting for the historian to analyze how German-English agreements drove the other adversaries to act quickly. It had to be now or never. As Kaiser Wilhelm II wrote after his abdication: “The French were afraid, even though for the moment they were assured of English support, that later the English would come to an agreement with the Germans at their expense.”2 In the final analysis, however, it seemed inevitable that at the decisive moment both the English and the German sides made mistakes, brought forth old resentments, and were not able to escape the traps of the previous years, including the Schlieffen Plan and English ties with France.

But these are all afterthoughts. At the time we were convinced that we had been attacked by our enemies and we were willing to defend ourselves. Somehow it leaked out that the 10th Jägers would mobilize in an accelerated fashion. To ensure that I did not miss anything, I took an overnight taxi to Goslar at the cost of 75 marks, only to learn that I had two more days. I was supposed to move out with a follow-on unit, the 2nd Field Battalion. There was nothing I could do about it. The only positive result was that I got to see my mother, who had come to Goslar for a few hours. Then she left. She later wrote my father, “Now he belongs to his comrades.”

Liège

We loaded up on 4 August. Amid thundering cheers the train drove into the night. It was an earnest, sincere enthusiasm. The whole country felt that there was no other way; it had to be done. I never once saw anyone drunk during the mobilization phase. The movement through Germany was like a triumphal march; everywhere the same excitement. Germany was united.

On 6 August we off-loaded in Malmedy and continued on foot toward our battalion. Liège supposedly had fallen. We moved via Thieux toward Louveigné. In a forest the first shots rang out, our advance elements were in contact with Belgian Franc-tireurs.3 The rumor that Liège had been taken was not confirmed. On the contrary, it appeared that things were not going right at the front. The supply trains of several regiments were flooding past us, all mixed up. People were telling the most horrific stories. We questioned a one-year volunteer from the field battalion who was sitting in one of the vehicles. Charging into a trench, he had received a rifle butt blow to his head, which knocked him unconscious. When the attack later advanced, he had been brought to the rear. But when we asked him about one officer or another, the answer was either “Dead!” or “Wounded!” With fixed bayonets we spent the night in the ditch along the road, numbed by the apparent defeat.

Scattered troops of the battalion arrived. They all talked about the heavy losses of mostly officers. They had stormed the Belgian trenches at night, but were then shot up by our own infantry. The mood of the troops was not really down. On the contrary, they all were mad at the Belgians. They were not real soldiers, and they maimed our wounded. After showing a white flag, they then fired on our exposed troops. Entire companies had surrendered to individual Jägers. And the Belgians were miserable shots, or such were the reports.

A battalion commander of Field Artillery Regiment Number 11 spent the night with us. We learned more from him. Six infantry brigades had been committed at night to take Liège. The most forward troops had already broken through and penetrated partially into the suburbs of Liège when heavy friendly fire forced them to retreat. The units had been completely disrupted. During the withdrawal the populace rebelled. Anyone who became separated from his unit faced potential death from ambush. Units marching through villages usually had their supply trains ambushed. Shots were fired from all the houses. When the battalion of Field Artillery Regiment Number 11 passed through Louveigné they were shot at from all the houses. The battalion commander set up one battery and destroyed the village. Horror stories upon horror stories, and all were believed.

On 8 August the situation became clearer. Liège had actually fallen. Singing, we advanced toward the field battalion, down the hill near Louveigné. A dark cloud hovered over the village with rising flames. That had been their summary punishment. In the town we encountered the first dead bodies of Belgian farmers, small people with grimacing faces full of anger and deadly fear. Cattle were running around without their masters. A few women squatted with the remnants of their belongings, staring with empty eyes. This was our first glimpse of war.

At noon we arrived at the battalion. Seven officers and 150 Jägers were dead, wounded, or missing, most of them through friendly fire. Liège has occupied my thinking repeatedly ever since. It had been a clear victory for the troops, but the mid-level and the higher leadership had not been up to the situation. Nobody except Ludendorff had shown the resolve to work through the crisis. Generals who later became highly proven leaders had failed here. What had happened? The troops had been deployed without training into this hasty attack. Night fighting was not the strong suit of the German Army. The mid- and lower-level leadership was not prepared for the required tasks. They were forced to learn on the battlefield.

That was the situation on 8 August. The Belgians were withdrawing to the west, the Germans to the east. In between lay the forts of Liège, still defended by their occupants. In the city of Liège itself, Ludendorff had a single brigade. His tough will and the recklessness of his personality had carried him through. This success was his alone.

The events of the next few days pushed us back and forth. Once again we passed through Louveigné. We were ordered to take all male inhabitants prisoner because shots rang out constantly during the night. We picked up sixty-two. In the parish rectory a bloody Hussar’s uniform was found. The rectory went up in flames. Nobody thought of the possibility that the village priest might have been caring for a wounded Hussar. Despite a general sense of consternation, the prisoners were not shot, but hauled away to do forced labor.

I was a platoon leader in the 2nd Company, which I had joined. The platoon leaders along with me were Reserve First Lieutenant Nottebohn, who became a professor and noted food chemist in Hamburg, and Reserve Second Lieutenant Jung, who became the chief judge of the state court in Breslau and was also one of the defenders of that city in 1945. In 1918 all three of us returned to Goslar as company commanders, all wounded many times over. Jung and Nottebohn were among our best officers during the war.

Near Hermalle we crossed the Maas River on 14 August. Belgian government flyers were posted on the walls of all the houses, warning everyone not to approach us with weapons in hand. East of the Maas the poster warnings were a bit more ambiguous, urging the citizens to delay the advance of the enemy.

Onward into France

In the meantime we were attached to General Georg von der Marwitz’s II Cavalry Corps. The French cavalry was near Ramillies Offues. Enemy bicycle troops occupied the hill. Dust was rising near the edge of a forest. Glimmering in the sunshine we could see a heavy concentration of French cuirassiers, still wearing chest armor and shiny helmets. Then things started to happen on our side, too, with machine gun fire reverberating and artillery firing. Like lightning the bicycle unit jumped off their bikes, dropped down, and started to fire. Horses reared as shrapnel exploded along the edge of the forest. Then we attacked. The French fired nervously, aiming too high. Then they abandoned their positions. On the hill they left some bicycles, rifles, and uniform items. The 29th Jägers took several prisoners, two artillery pieces, and two machine guns. As we stormed up the hill, a farmer fired from behind from the roof of his house on our advancing battalion. The farmhouse was set ablaze, and as I noted in my journal at the time, the farmer hanged himself. Those were the facts we were convinced of then. Today, I am certain that the puffs of smoke from the roof of the farmhouse were shots from French scouts who were aiming too high. But who knew then that the impact from an infantry rifle bullet created a sharp bang and a dust cloud?

A Jäger detachment was formed from the 10th, 4th, 9th, and 7th Jäger Battalions.4 Our commander took overall command, and Captain von Rauch took over our battalion. I became the adjutant, even though I was still a Fähnrich.

On 19 August we made contact with the enemy again. French shrapnel hit the tightly advancing columns. I had to clear my way back to the battalion with drawn saber through the quickly withdrawing cavalry. Toward the evening we were positioned south of the Bois de Buis. Several times I rode across the battlefield from company to company through artillery fire, withdrawing cavalry, and French patrols.

Up until the fall of Brussels we received the latest Belgian newspapers every day. At first the Belgians reported they were winning near Liège, then west of Liège, then between Liège and Brussels, then near Brussels, and then it was over. We were most amused with the portrayals of morale. The feared German Uhlans5 supposedly were giving themselves up by the hundreds because of hunger. We were portrayed as just a bunch of hoodlums that were kept together by the whip, and not wanting anything to do with war. Berlin was in revolution and the Kaiser had been murdered. The Belgian press, of course, had nothing but high praise for the Belgian and French soldiers. “What human beings! Such character!” wrote a correspondent about French soldiers near Dinant. A German prisoner was quoted as having said, “The Belgians, they’re not just soldiers, they’re lions!” A Belgian corporal reportedly killed single-handedly all the members of an entire German battery. Cannons towed by thirty-two horses had supposedly arrived in Liège. “A good prey for our brave soldiers.” General Otto von Emmich supposedly had lost his Pour le Mérite for filing false victory reports . . . so on and so forth.

The German cavalry was moved to the right flank and the enemy withdrew from Belgium. We were fighting against French cuirassiers. Dismounted, they defended themselves in an orchard. Their shiny helmets and chest armor, red trousers, and high boots with knee pads hindered them from handling their carbines and fighting on foot. How irresponsible it was to send human beings into a war in 1914 with equipment that had not changed since the Napoleonic Wars.

On 24 August we seized Tournai, fighting against French territorial defense units. We captured one general officer, one colonel, and six hundred soldiers. The numerous enemy dead proved the superior marksmanship of our Jägers. Neither backyards, nor street fighting, nor poor terrain could stop the momentum of our attack. Shots rang out along the streets and impacted with a sharp bang into the houses behind us. We again heard cries that the Belgians were shooting at us from the rear. Supposedly shots were even fired at us from the steeple of the cathedral. In the confusion and tenseness of the street fighting and the anger about the supposed involvement of civilians in the fighting, a cannon crew grabbed a bunch of them and used them as human shields to move a gun forward. The human shield disappeared as the barricades and the houses crumbled under the close-range artillery barrage. I was able to prevent an artillery volley directed against the cathedral. Throughout my life architecture was my hobby. My war hysteria was slowly melting away.

Tournai

Once we were in the city we received the following order from the cavalry corps: “Take as hostages in Tournai the mayor and two hundred citizens, to include the highest church official plus twenty priests. Bring them to Ath. Disarm the citizens’ militias; collect all the weapons; seize all the cash boxes; remove all the flags; destroy all the post, telegraph, and rail installations; demand 2 million francs in reparations; threaten to destroy and burn the city, to include all monasteries and churches. Execute this threat at the least sign of resistance by the citizens or in the event that German military personnel come under fire.”

This order was given because some of the citizens had shot at German troops from the rear. The staff of the 10th Jäger Battalion was charged with the execution of the order. I picked two Oberjägers6 and twelve Jägers from my old platoon as a security and covering force. The remainder of the battalion and the cavalry moved on and only my commander, Captain von Rauch, and I remained behind in the city, negotiating with the mayor. His face showed his shock. He finally ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Maps

- Foreword by Carlo D’Este

- Preface

- Introduction

- 1. 1914

- 2. 1915

- 3. 1916

- 4. 1917

- 5. 1918

- 6. Retrospective on World War I

- 7. 1919

- 8. 1920

- 9. 1921

- 10. In the Third Reich

- 11. World War II

- 12. Greece

- 13. Russia

- 14. 1942

- 15. 1943

- 16. The Gross-Deutschland Division

- 17. Commander in Chief, Army Group G

- 18. North of the Danube

- 19. Looking Back

- Appendixes

- Notes

- Index