- 514 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

A War of Logistics

The First Indochina War ran from 1945 to 1954 and has been described as “a war in which logistics decided the outcome.”1 Indeed, every aspect of the struggle between the French Union forces and the Viet Minh for the control of Indochina was permeated by logistical considerations, and the way in which the French and their Viet Minh opponents organized and employed their logistical resources to meet the physical and operational challenges of the war determined in large part the outcome of not only the battles and campaigns, but the overall conflict. For both sides the objectives, scope, timing, duration, and general nature of all major operations were determined in large measure by logistical constraints, particularly the means of transporting men and materiel to the area of operations. Every campaign constituted a test of the efficiency and effectiveness of the logistical systems of the opposing forces upon which rested victory or defeat.

The efforts of the French and the Viet Minh to develop efficient and effective logistical systems in Indochina were shaped by both the physical environment and their respective internal political, social, and economic situations. The difficult terrain, harsh climate, great distances, and limited transportation infrastructure of Indochina had a profound impact, as did the commitment of each side to the struggle, the national resources of money, men, expertise, and materiel that they could bring to bear, and outside support. To a very great degree their respective national goals, level of technological sophistication, and very different military philosophies also shaped not only their strategy, tactics, and organization of combat forces, but their respective logistical doctrines and organizations as well.

In addition to the common challenges faced by both opponents, each of them also faced a number of more specific challenges that particularly influenced the evolution of their respective logistical systems. For the French Union forces, the specific factors that shaped their supply and transportation systems included the magnitude and diversity of the forces supported, the necessity of converting what was essentially a static support system into one capable of supporting mobile forces in extended operations over a wide area, and the restrictions on air and ground transport imposed by the physical environment and enemy action. For the Viet Minh, the unique challenges that shaped their logistical support system included an initial lack of logistical experience and technical expertise, the vulnerability of their logistical facilities and lines of communication to French airpower, and a comparatively low level of military technology.

The Physical Environment

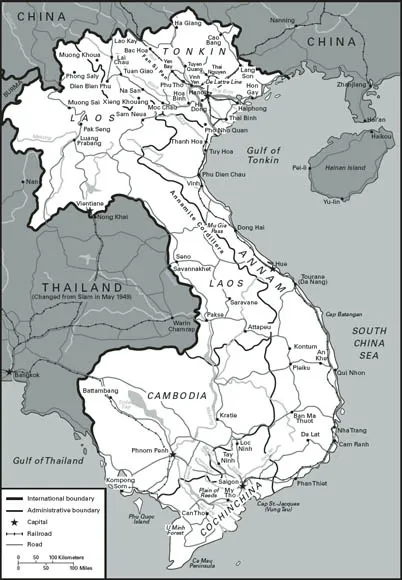

Perhaps no single factor had a greater impact on the organization and employment of both French Union and Viet Minh forces than did the physical environment of Indochina. The terrain and climate of Indochina are generally unfavorable for large-scale conventional military operations.2 The steep mountains, dense forests and jungle, abundant waterways, swamps, and intensely cultivated rice paddies with their dikes and drainage ditches restrict cross-country mobility even on foot during the dry season and make large areas virtually impassable during the rainy season. The difficult topography and limited transportation infrastructure (see map 1.1) combine to impede motorized transport and to limit vehicular traffic to a few constricted routes. Armor operations, while not impossible, are severely restricted. The dense vegetation that covers most of Indochina also limits mobility while providing excellent concealment and ambush sites. As one French staff officer noted, “Although the terrain is never absolutely impenetrable, its nature is such as to confer upon it a coefficient of penetrability which exerts a direct and profound influence upon the nature and the rhythm of the operations.”3 A French correspondent, Lucien Bodard, described the situation even more succinctly, “From mountain peak to mountain peak, it was a Fenimore Cooper kind of war.”4

The monsoon climate of Indochina as well as the consistently high humidity and temperature also affect military operations to an important degree. Rain and fog restrict visibility both on the ground and from the air and limit flying operations during the rainy season. The floods, swollen streams, washouts, landslides, and mud that accompany the rainy season further restrict ground mobility. The timing and tempo of combat operations are thus largely determined by the prevailing climatic conditions. Accordingly, most major combat operations during the First Indochina War took place during the dry season from October to May. Of the twenty-six offensives launched by the Viet Minh against the French between September 1952 and July 1954, nineteen were initiated during the relatively dry “winter–spring” season, and of the other seven, four were continuations of attacks begun during the preceding dry season.5

To the hazards of terrain, vegetation, and climate must be added the impact on personnel of a generally unhealthy climate, disease, and dangerous fauna. The heat and high humidity prevalent throughout most of Indochina as well as torrential rain during the rainy season can take a high toll on the soldier. Serious diseases, including malaria, dengue fever, cholera, hepatitis, typhoid, and tropical ulcers, are common. For example, between 1950 and 1954 about one-fourth of all French Union troops were infected by schistosomiasis and leptospirosis.6 Most of Indochina is also infested with leeches, a variety of biting insects, crocodiles, and poisonous snakes, including the cobra, krait, eyelash viper, and sea snake.7 Attacks by tigers, wild elephants, and wild pigs are not unknown. “And,” as one historian has written, “there were rats, big and savage, that could find their way even into a jungle fort’s bunkhouse to bite through a sleeping soldier’s boot into his foot.”8

Map 1.1. Geography of Indochina.

The military problems posed by the inhospitable environment of Indochina were compounded by the lack of a well-developed transportation system.9 Transoceanic and coastal water transport were important links in the military supply system of the French—and to a lesser degree of the Viet Minh. However, the limited development of Indochinese ports restricted major military cargo importation to only a few major ports, principally Saigon and Haiphong, both of which were perpetually clogged. Natural conditions limited the military use of inland waterways, few of which were improved sufficiently to support heavy, sustained military personnel and cargo movements. The limited rail network, its capacity degraded by the poor condition of the existing right-of-way, was also inadequate to support major military movements. Moreover, the many culverts, bridges, and tunnels made the Indochinese rail system extremely vulnerable to sabotage and ambush. Similarly, the highway network of Indochina was not well-suited to support military operations in the more remote regions, particularly northwestern Tonkin, Upper Laos, and the Central Highlands. The lack of routes into the remote areas, inadequate road construction and maintenance, and the vulnerability of bridges, culverts, ferries, and other facilities to the effects of both climate and enemy action restricted the military use of the Indochinese highway network for both the French and the Viet Minh, although the impact was greater on the more motorized French Union forces, which consequently relied increasingly on air transport for the rapid movement of personnel and supplies. Even so, the few all-weather airfields available in Indochina were inadequate and poorly positioned to support sustained airlift operations, and the construction of new airfields was both expensive and technically challenging.10

One additional geographical factor that has been little recognized but which made military operations in Indochina more difficult for both the French and the Viet Minh was the lack of accurate maps. Much of Indochina was uncharted by the French, and the maps that did exist were frequently inaccurate. The lack of adequate maps and accurate survey data adversely affected the plotting of artillery fires and air strikes, the location of airdrop and paradrop zones, route reconnaissance, and aerial observation as well as general operational planning. In the more remote regions, such as Upper Laos, it was even difficult to obtain native guides, since the inhabitants were so isolated that they frequently were unfamiliar with the terrain outside their home valley. The deficiencies of their maps were never fully corrected by the French, as became readily apparent to U.S. military personnel in the early 1960s. U.S. forces subsequently resurveyed almost the entire region using aerial photography.

The impact of terrain and climate on logistical operations was particularly profound. The difficult terrain forced both sides to decentralize their logistical operations and to reduce as much as possible the logistical burden on combat units. The prevailing conditions also limited motor transport operations, for which the French substituted air movement and the Viet Minh substituted manpower. Food and equipment deteriorated rapidly in the hot and humid climate of Indochina, and the corrosive effects on weapons, vehicles, and aircraft of salty coastal air and dust during the dry season were significant.

The prevailing environmental conditions and poor transportation infrastructure affected both sides, but tended to favor the more lightly equipped Viet Minh and the guerrilla tactics that they employed throughout most of the war. In general, the Viet Minh proved more adaptable to the physical environment in which the war was conducted. They became very adept at conducting relatively large-scale movements on foot over the difficult terrain and at utilizing the dense vegetation for concealing such movements from French aerial observation. They also made excellent use of heavily forested areas for concealing their supply installations and for preparing ambushes against the usually road-bound French Union forces.

Despite the considerable resources at their command, the French proved relatively inflexible and unable to adapt to the hostile physical environment. The highly mechanized French Union forces were frequently thwarted by the lack of adequate roads, obstacles to cross-country mobility, and poor trafficability, particularly in the rainy season. The one significant French advantage, airpower, was largely negated by frequently poor flying conditions and the hazards of flying in the largely uncharted mountainous regions. In sum, as contemporary U.S. intelligence officers noted, “In a country where mountains, forests, swamps, waterways, and rice fields make movement off the road virtually impossible for vehicles other than amphibians or tanks, the guerrilla-like Viet Minh have a great advantage of tactical mobility over the French ground forces.”11 Indeed, the physical environment of Indochina offered opportunities as well as challenges for the antagonist who was prepared to seize them.

The Operational Environment

The changing operational environment also had a profound impact on the development of the logistical systems of both sides. Operationally, the First Indochina War can be divided into two main periods set apart by the beginning in 1949–1950 of large-scale logistical support of the Viet Minh by Communist China and of the French Union forces by the United States.12 Before 1950, the war in Indochina was largely confined to small-scale guerrilla and counterguerrilla operations that did not seriously strain the logistical structure or the logistical resources of either side. With the increased resources available to both sides after 1950, the tempo and scope of the war increased and it became, at least in Tonkin (the key theater of operations), a conventional war involving large, well-armed forces engaged in extended, complex offensive operations covering wide areas. Such operations imposed additional support requirements that in turn required substantial changes in the logistical organizations and methods of both sides.

The two logistical systems that evolved between 1945 and 1954 differed significantly in size, structure, technological level, doctrine, and methods, but it was their relative efficiency and effectiveness in overcoming the various environmental and operational challenges that they faced that in the end determined the outcome of the First Indochina War. Although size and technological sophistication seemed to give the French an overwhelming initial advantage, they in fact imposed tremendous logistical burdens with which the French were unable to cope.13 Commenting on that fact, American historian Ronald H. Spector wrote: “Observers also tended to err in assessing the French supply and transport system as superior to that of the Viet Minh. In fact, the reverse was true, for the road-bound French supply convoys, with hundreds of trucks constantly exposed to ambush, were far more vulnerable and less flexible than the primitive Viet Minh supply services.”14 Ultimately, it was the simpler and less technologically advanced Viet Minh system that proved better adapted to the existing physical and operational environment and thus more effective.

The degree to which logistical considerations influenced the nature and outcome of the war differed for each of the two opponents. Although both the French and the Viet Minh faced many of the same logistical challenges imposed by the physical and operational environment, their reactions were quite different, and in effect there were two wars fought simultaneously in Indochina between 1945 and 1954.15 The French war against the Viet Minh was essentially a limited struggle to regain and maintain control over a hostile (or at best indifferent) population, a war with a very definite air and water dimension especially in the logistical arena, and largely a war of position and a contest for control of the few available lines of ground communication. The Viet Minh war against the French was a total war for national liberation, almost exclusively a ground war, and very much a war of mobility. Furthermore, for the Viet Minh the main battlefield was largely confined to the Red River delta and the hills and mountains of Tonkin and Upper Laos, while for the French the entire length and breadth of Indochina had to be considered. The difference in the war from the Viet Minh and French perspectives was clearly understood by Ho Chi Minh and Vo Nguyen Giap, the leaders of the Viet Minh, but it seems to have largely escaped the notice of the higher level commanders and staff officers of the French Union forces despite the fact that the warning—“REMEMBER—THE ENEMY IS NOT FIGHTING THIS WAR AS PER FRENCH ARMY REGULATIONS”—was prominently posted in the French guerrilla warfare school in Tonkin and appeared on the masthead of the school’s monthly magazine.16

The very different nature of the two “wars” that comprised the conflict in Indochina can best be seen by studying the three main campaigns into which the operational logistics history of the war can be divided. These three logistical campaigns overlapped each other and extended over the entire course of the war, but each dominated a particular temporal period to which they gave a particular character.

From the logistical point of view, the first campaign of the Indochina war was fought in the period between the return of French forces to Indochina in August 1945 and December 1950. This was the period in which both sides built up their forces, worked out their strategy, and developed their logistical doctrine and organization while conducting mainly small-scale guerrilla and counterguerrilla operations that did not seriously strain their logistical resources. The initial phase, in which both sides sought a political accommodation, ended with the Viet Minh uprising in the Haiphong-Hanoi area in December 1946. Unsuccessful in their first attempt at a conventional victory, the Viet Minh retreated to their protected base areas north and south of the Red River delta and subsequently concentrated on building a main battle force capable of defeating the French Union forces in large-scale conventional operations. Harassed by sabotage, ambushes, and local guerrilla attacks on isolated outposts, the French worked to develop their forces and a strategy that would facilitate their efforts to regain control of...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Maps, Tables, and Figures

- Table of Equivalencies

- Note on Translation, Acronyms, and Measurements

- Preface

- 1. A War of Logistics

- 2. French Union Combat Forces

- 3. Viet Minh Combat Forces

- 4. French Logistical Doctrine and Organization

- 5. Viet Minh Logistical Doctrine and Organization

- 6. The Opposing Transport Systems

- 7. French Sources of Supply

- 8. Viet Minh Sources of Supply

- 9. The Shape of Battles to Come

- 10. The Campaign for the Base Areas

- 11. The Campaign for the Lines of Communication

- 12. Planning and Buildup for the Battle of Dien Bien Phu

- 13. The Limits of Aerial Resupply

- 14. The Triumph of the Porters

- 15. Logistics and the War in Indochina, 1945–1954

- Notes

- Glossary of Abbreviations, Acronyms, and Terms

- Selected Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access A War of Logistics by Charles R. Shrader in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Asian History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.