eBook - ePub

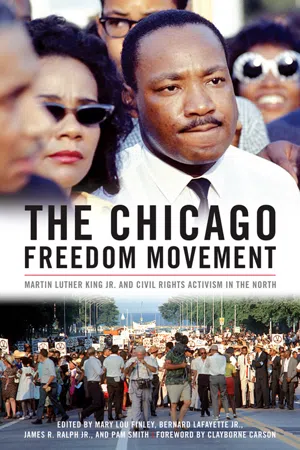

The Chicago Freedom Movement

Martin Luther King Jr. and Civil Rights Activism in the North

- 528 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Chicago Freedom Movement

Martin Luther King Jr. and Civil Rights Activism in the North

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Chicago Freedom Movement by Mary Lou Finley, Bernard LaFayette, James R. Ralph, Pam Smith, Mary Lou Finley,Bernard LaFayetteJr.,James R. RalphJr.,Pam Smith,Bernard LaFayette Jr.,James R. Ralph Jr. in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

The University Press of KentuckyYear

2016Print ISBN

9780813175003, 9780813166506eBook ISBN

9780813166513Part 1

Living the Chicago Freedom Movement

1

In Their Own Voices

The Story of the Movement as Told by the Participants

American popular culture likes to simplify complex issues. The Chicago Freedom Movement has often been depicted as a contest of wills between Martin Luther King Jr. and Mayor Richard J. Daley, with Daley “winning” and King “losing.” That depiction is misleading. The Chicago Freedom Movement was a mass movement driven by inspired leadership and with the broad involvement of a community fed up with decades of entrenched inequity and abuse.

The strength of the Chicago Freedom Movement came from people seeking to make lasting changes in their communities. In this opening section, the story of the Chicago Freedom Movement is told in the words of those who were present and made numerous personal sacrifices to better the lives of current and future black Chicagoans. The recollections of a few are offered here as representative of the many who gave their time and energy to make the Chicago Freedom Movement what it was. While most of the voices here belong to Chicago Freedom Movement activists, the perspectives of others who were involved in the broader upheaval the movement caused are also included. As editors, we have added material to contextualize the participant accounts.

The Chicago Freedom Movement stood on the shoulders of earlier generations of activists in Chicago. And that is a long list of people, starting with John W. E. Thomas’s pursuit of civil rights in the Illinois legislature in the aftermath of the Civil War, Ida B. Wells-Barnett’s fight against lynching in the early 1900s, Earl Dickerson’s quest to end restrictive covenants in the 1930s and 1940s, James Farmer’s and Bernice Fisher’s vision for the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) in the early 1940s, and Charles Hayes’s and Addie Wyatt’s broad vision for civil rights unionism in the 1940s and 1950s. When the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) arrived in 1965, Chicago activists were not wringing their hands and waiting for a rescuer. The struggle was already under way to end inadequate schools, horrible housing conditions, and the pernicious, predatory practices of the real estate industry.

Two struggles in particular laid the groundwork for the Chicago Freedom Movement: the schools campaign and the campaign to improve poor housing conditions on the West Side.

Prelude I: Organizing for Better Schools

This critical phase of the 1960s Chicago civil rights movement sprang from the mounting distress of black parents and their children over unequal education in Chicago’s public schools. In the aftermath of the famous Brown v. Board of Education decision, the Chicago NAACP claimed that Chicago’s schools suffered from deliberate segregation. Unlike in the American South, that segregation resulted not from formal Jim Crow laws but from administrative policies. In early 1962, on the city’s Far South Side, black parents and students expressed the depth of their frustration by organizing protests at the Burnside School. Alma Coggs was a leader in the fight for better education at Burnside:

We were living in public housing and [had] three children. We looked for a house, and we found one on Vernon Avenue. That was in 1951; that’s when we moved to Vernon Avenue from way out in Altgeld Gardens at about 130th; and this was 9330 Vernon. It was a very stable neighborhood, but in the area around it, a little further away, all of the white families were just moving, hastening to move because of the school situation. The Burnside School became overcrowded, after not being crowded at all. We had another school about five blocks away, and that school was actually underused. It had ten empty rooms, while Burnside was built for 800 and had close to 3,000 students. That is how overcrowded it was! They would not admit any of the kids from our area to the other school, Perry Elementary.

That is how that got started. We had asked the school district as parents, we had asked them as a community, and we had asked them as the school. The Burnside School had asked to place some of the kids over there; they just said “no,” and we felt that was really what you call gerrymandering.

Instead of 9 a.m. to 3 p.m. our school had to go into something like 8 a.m. to 1 p.m. and 1 p.m. to 4 p.m. shifts: double shifts. Most of the parents were very upset about that. They just thought that that was terrible. It was hard on the teachers because you had many more students than they could handle; then the discipline became pretty bad, the kids started acting ugly, and the teachers could not handle them.

For the parents and others in the community it just got to be too much. We’d had it. It wasn’t something that was planned outside. It was something that was kind of spontaneous because it was so logical. And two or three people suggested—of course, you know, when you get the NAACP and those different groups involved—the first thing they said was “let’s picket.” . . . We had a very good PTA and it just happened that I was president of the PTA; that is how I became the spokesman for the actions. So we actually sat down and planned it, and the parents really took part. We were just protesting the fact that they ignored us, and we felt that if they allowed our students to go to school over there it would alleviate some of the problems we were having.

A lot of the parents said that we will be there, we will come out, and we will support it. We are not going to let you do it by yourselves. So not only did the parents come, but the ministers in the area also came.

The initial group was largely women, but there were quite a few men that supported us. They were apprehensive, especially once the police got involved when the Board of Education was ordering the parents out of the school. At first we were just picketing in hallways and in the school building and they asked us to leave. A lot of the folks said, “Don’t leave.” The police just told them that “it’s our duty—we’ve been ordered—to put you out; and if you don’t go peacefully we will have to arrest you.” And so that is what they did. Some of the people decided that they could not afford to be arrested. And we said, “Well, why not? Let’s see if that will accomplish anything.” But it did not, really. They did actually lock up about fifteen of us. We decided we would not go back and be locked up again. We would do our picketing outside. And so that continued for two to three weeks.

In the meantime, in the evenings afterwards, there would be meetings, and different groups wanted to meet with us and see what they could suggest. And so they had a big community meeting, and they decided on trying to sue the Board of Education. With the help of the NAACP and other outside groups, we actually sued the Board of Ed for the right to transfer our children.1

Protests erupted in other city neighborhoods, and legal action was pursued in support of equal opportunity in public education. The ferment led to the founding of the Coordinating Council of Community Organizations (CCCO) in late 1962. Meyer Weinberg was a professor at Wright Junior College in the late 1950s and early 1960s and a member of Teachers for Integrated Schools, one of the first groups to join CCCO. He recalls how he learned about the extent of segregation in the Chicago public schools:

I really didn’t know much about the history of segregation in Chicago so I had to learn it. And my teacher was Faith Rich of CORE. She had been active on the school issue starting in the 1950s. She had also coauthored an article in Crisis in 1958 with Rita Phillips called “De Facto Segregation in the Chicago Public Schools.”2 It was news to me. It became clear, at least to me, that this whole distinction between de facto segregation and de jure segregation was a fake kind of distinction, a distinction without a difference, and that segregation in the North was a conscious creation of the school system working along with city government.3

Al Raby entered the Chicago civil rights movement through Teachers for Integrated Schools. He describes his early involvement:

Meyer Weinberg called together a group of teachers and said essentially that some segment of every profession in the country had taken a position on integrated education. He had been unsuccessful in getting the teachers’ union to take a position and thought that we ought to form an organization speaking to those issues. That organization was called Teachers for Integrated Schools. In the early 1960s he and I, then, became delegates to the Coordinating Council of Community Organizations, which was a broadly based civil rights, civic, community umbrella started by the Urban League and The Woodlawn Organization. So it was as a delegate to the Coordinating Council of Community Organizations that I first became involved in the movement of the 1960s.4

Despite the protestations of black Chicagoans, superintendent Benjamin Willis and the Board of Education refused to acknowledge the existence of a problem in the public schools. CCCO leaders decided they had to make an even more dramatic plea for change, so they organized a boycott in October 1963 in which more than 225,000 black youths stayed home from school. More than 175,000 black students participated in a second boycott in February 1964. Meyer Weinberg recalls the first school boycott in the fall of 1963:

It was not spontaneous in any sense. It was well thought out. For instance, I remember getting a phone call from the PTA at Marshall High School which has been a black school since the late fifties, early sixties. I got called because I was chairman of the Education Committee of CCCO—this was less than a week, maybe three days before the first boycott. And they had a lot of questions to ask about whether they should keep their kids out. So I went there and I told them I graduated from this school [in 1938], and that when I went to it, it was a first-rate school, really a fine school, and that there is no reason why it can’t be for your children too. They were worried about the legal situation. There was a state law in Illinois that if you kept your child out of school for three consecutive days for reasons other than sickness you could be arrested for abandoning your children. [The boycott lasted one day.] It was a mass sort of thing. A quarter of a million kids were kept out, and that’s as many as there were on the March on Washington.5

David Jehnsen, organizer of the West Side Christian Parish’s youth group, gives this account of another action on the school issue:

In 1963 we changed the name of the Parish’s youth group from the Loyal Hearts to the Parish Youth Action Committee, and I worked with Alan Howe, another Parish volunteer, to train them in nonviolence and civil disobedience. We used the Nashville Sitin Movement White Paper, Dr. King’s Stride toward Freedom, my notes from a nonviolence workshop Bayard Rustin had given in preparation for the March on Washington, and a few pamphlets on Gandhi’s philosophy and the steps [in a nonviolent campaign].

In 1963 and early 1964 Chicago civil rights organizations were boycotting segregated schools to try to get rid of Ben Willis, the Superintendent of Schools. While even at this early stage we knew that simply removing the superintendent couldn’t solve the problem, we also thought we needed to be involved with the civil rights organizations in their efforts. The Parish Youth Action Committee leaders essentially took over the Crane High School Student Government and on one occasion led a five- to six hundred student march to downtown Chicago to support a demonstration at City Hall. The civil rights groups hadn’t seen this type of student involvement before and there was new credibility for the work we were doing on the West Side of Chicago.6

Rosie Simpson, one of those who boycotted and led demonstrations against Superintendent Willis, recalls the grassroots flavor of the early Chicago demonstrations:

I’d already been wrestling with the school district on severe overcrowding and segregation issues when I started going down to the Board of Education to find out what the plans were for our kids. And I found out that they were going to set up a bunch of “Willis Wagons” [portable classrooms] between the railroad tracks and the alley, and that’s where they planned to send our kids to school. We decided as parents we were not going to allow that to happen. We decided that when they came out to build that school we were going to lay down in fr...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Foreword

- List of Abbreviations

- Introduction

- Part 1. Living the Chicago Freedom Movement

- Part 2. Background and History

- Part 3. The Impact of the Chicago Freedom Movement

- Part 4. Stories from the Chicago Freedom Movement

- Part 5. Lessons Learned and the Unfinished Work

- Epilogue: Nonviolence Remix and Today’s Millennials

- Acknowledgments

- Chronology

- Selected Bibliography

- List of Contributors

- Index