![]()

1

Precedents and Back-Channel Games, 1968–1970

He, Nixon, was aware that I, the Soviet Ambassador, had “successfully and without any publicity” maintained confidential ties that Presidents Kennedy and Johnson had had with the Soviet Government…. In that connection, he is designating his chief aide, Kissinger, for such contacts with me.

—Anatoly Dobrynin to the Kremlin, February 1969

Aside from the Watergate scandal that led to the only presidential resignation in U.S. history, Richard Milhous Nixon is usually associated with three foreign policy initiatives: the opening to China, the end of American involvement in the Vietnam War, and détente with the Soviet Union. The fact that these three major foreign policy initiatives relied on back-channel diplomacy was a product not only of design but also an underlying philosophy about secrecy and the conduct of international relations. Nixon and his special advisor for national security affairs, and later secretary of state, Dr. Henry Kissinger, carefully managed and compartmentalized confidential exchanges, often without the knowledge of the Departments of State and Defense. From the beginning of the administration, these men consciously centralized the policymaking machinery in the White House–based National Security Council (NSC).1

U.S.-Soviet back channels suited both the Kremlin and the White House and had begun before Nixon assumed office in 1969. This chapter traces the development of the Nixon administration’s foreign policy structure, early back-channel overtures to the Soviets, the evolution of bureaucratic rivalries within the administration, and the early development of the Channel between Kissinger and Dobrynin. Once in place, the new Nixon administration quickly established the foundation of back-channel dialogue and created mechanisms that would later become the central venue of U.S.-Soviet relations and the shaping of détente. Trends that became apparent in 1971 and 1972 had their origins as bureaucratic actors maneuvered and the Soviets and the new administration became more comfortable with each other.

Richard Nixon assumed the presidency on January 20, 1969, as arguably one of the best prepared of his predecessors when it came to foreign policy. Inside and outside public office, Nixon cultivated contacts with world leaders, traveled extensively, read widely, and wrote about the larger world for a sizeable audience.2 Regardless of his own credentials, Nixon has been forever linked with Henry Kissinger. The Harvard-educated Jewish refugee from Nazi Germany, a naturalized American and professor at Harvard’s prestigious School of Government, became Nixon’s primary policy implementer.3 If Nixon was the architect, Kissinger was the builder. Like any relationship, the one between the president and his national security advisor changed over time, with peaks and valleys shaping the landscape along the way.4 In a White House where the chief of staff, H. R. “Bob” Haldeman, served as a gatekeeper to the president, Kissinger was among the few assistants who had regular and consistent access to Nixon.5 Kissinger also served as Nixon’s personal liaison in a web of back-channel negotiations and alternate diplomatic arrangements with friend and foe alike.

Many back channels existed—and not just with the Soviet Union. The Nixon administration regularly bypassed the State Department’s cable system via the Situation Room in the White House basement, sending coded communications to foreign leaders and American ambassadors stationed abroad. For example, Kissinger communicated directly with the U.S. ambassador to Pakistan, Joseph Farland, who served as an emissary to Pakistan’s military dictator, President Agha Mohammad Yahya Khan (hereafter referred to as Yahya). Kissinger also arranged a back channel through the U.S. ambassador to Bonn, Kenneth Rush, known as the “special channel,” to communicate with West German state secretary Egon Bahr and West German chancellor Willy Brandt. In early 1971, Kissinger communicated with Bahr through a covert navy operation based in Frankfurt, complete with specially encrypted messages.6 The “special channel” with the West Germans affected the Kissinger-Dobrynin channel as the United States responded to Willy Brandt’s policy of improving relations with the Communist East (Ostpolitik), and in the negotiations over the Quadripartite Access Agreement on Berlin signed in September 1971.

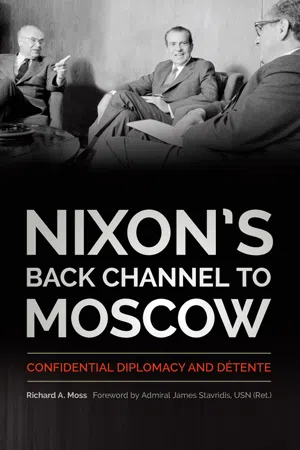

Republican presidential candidate Richard Nixon and President Lyndon Johnson face each other across the table of the White House Cabinet Room, July 1968. Once elected, Nixon used early back channels with the Soviets to kill the idea of an early summit meeting between the Soviet Union, the outgoing Johnson administration, and the incoming Nixon administration. (LBJ Library, WHPO. LBJ Library photo by Yoichi R. Okamoto)

The back-channel interlocutors, Anatoly Dobrynin and Henry Kissinger, in the White House Map Room, March 1972. Decades later, Dobrynin inscribed a copy of his memoir, In Confidence, to Kissinger: opponent, partner, friend. (RNPLM)

Under Nixon’s general guidance and agreement, Kissinger reformulated the foreign policy machinery and centralized power in the NSC system.7 Kissinger worked vigorously to put Nixon’s and his own imprint on the system. As the president’s special assistant for national security affairs, Kissinger chaired a number of committees under the umbrella of the NSC, giving him an institutional-bureaucratic advantage over the secretaries of state and defense. Kissinger supervised the work of the Senior Review Group (SRG), an interagency group that discussed policy option papers, and the 40 Committee, which oversaw covert activities.8 Kissinger also spearheaded the Washington Special Actions Group (WSAG), an NSC subcommittee for crisis management and the preparation of contingency plans, which was set up after the North Koreans shot down an American EC-121 reconnaissance plane in April 1969.9 The NSC-based foreign policy was also a source of bureaucratic conflict.

Although he had been one of Nixon’s few close personal friends since the 1940s, Secretary of State William P. Rogers was gradually relegated to irrelevance by the administration’s conduct of foreign policy generally, and the use of back channels specifically. According to Kissinger, the use of back channels to circumvent Rogers began “the day after Inauguration.”10 Efforts to bypass the State Department had begun earlier, when Nixon set up early back channels with the Soviets during the 1968 presidential campaign and the postelection transition period through Robert Ellsworth and Henry Kissinger. Back channels and secret policy initiatives continued through Nixon’s time in office, often without Rogers’s knowledge. By the autumn of 1971, Rogers had been almost completely circumvented on détente, the opening to China, and even the Middle East. In May 1972, just days before the departure to the Moscow Summit, Nixon told Kissinger, “Be sure you warn Gromyko and obviously Brezhnev that they’ve got to be very careful not to talk about the special channel where Rogers is involved.” The president cautioned, “Because then we’d have to explain what the hell it is to him.”11 Even at this late date, approaching the end of the first term, Nixon wanted to keep Rogers in the dark.

Rogers’s diminished position became publicly known during Nixon’s first term, and the press usually focused on Kissinger. In a multipage spread in the New York Times Magazine in 1972, for example, Milton Viorst wrote how morale at the State Department and the Foreign Service had declined as a result of the conduct of foreign policy from the White House instead of the State Department’s headquarters on C Street. Although the headline read, “William Rogers Thinks Like Richard Nixon,” the first picture was actually of Kissinger with the caption, “Nixon’s national security adviser has been called ‘the Secretary of State in everything but title.’”12 As if to highlight the virtual insignificance of the State Department under Rogers, the Viorst article half-heartedly attempted to explain Rogers’s justifications about State’s diminished role in the foreign policy process. The article also devoted considerable space to Kissinger: “He is executive of the National Security Council and of the various interagency committees established under its aegis; the channel through which intelligence and memoranda are regularly conveyed to the president, and the president’s daily briefer on foreign-policy problems…. Because of his proximity to the president and his unlimited access to information, he is in a position to be the most powerful man in the foreign-policy process. And—except, perhaps, for the president himself—he is just that.”13

Viorst wrote before the extent of back-channel diplomacy became known. Behind the scenes, the back-channel modus operandi fanned the flames of a heated rivalry between Kissinger and Rogers, and by early 1971 Kissinger had the upper hand due to his indispensable role in the administration’s foreign policies.

In the bureaucratic gamesmanship, Kissinger found a willing collaborator in the president. In his memoir, Kissinger wrote: “Inevitably, Rogers must have considered me an egotistical nitpicker who ruined his relations with the president; I tended to view him as an insensitive neophyte who threatened the careful design of our foreign policy. The relationship was bound to deteriorate.”14 It was Nixon—not Kissinger—who excluded Rogers from the first official meeting between the president and Dobrynin in February 1969. It was Nixon who agreed to have Malcolm Toon—not Rogers—represent the State Department after the short one-on-one session in which the president endorsed the Channel.15 Rogers, a novice on foreign affairs, had ably served as the attorney general during the Eisenhower administration, and Nixon reportedly chose him for his lawyerly skills.16

In the White House, Rogers came to be seen as an occasionally useful bureaucrat and a front man, not a policymaker or even an implementer of policy. By contrast, Kissinger, with his deep German accent and scholarly credentials, lent an air of intellectual sophistication and structure to Nixon’s more abstract conceptions and political image. After three years in office, Nixon bluntly reflected behind the closed doors of the Oval Office about Rogers’s role. “[Rogers] made a big, old error in terms of his own place as Secretary of State and in history,” Nixon stated matter-of-factly to George Shultz and John Ehrlichman. “[Rogers] has panted so much to be liked by his colleagues at the State Department, that the State Department runs him, rather than his running the State Department. He has panted so much to be liked by the press that covers the State Department, that the press run him, rather than [he] them.” Rogers had failed, time and again, in Nixon’s eyes, to step up to the critics and pundits who criticized the administration.17

Nixon typically shied away from personal confrontation, and in handling the Kissinger-Rogers rivalry, he usually relied on strong men to mediate or keep in check personality conflicts in his administration. Nixon primarily delegated dispute resolution to Chief of Staff Haldeman, a task upon which Haldeman regularly and revealingly reflected in his handwritten and later taped diary. With their Teutonic-sounding names, Haldeman and chief domestic advisor John Ehrlichman were known as “the two Germans” and also as the “Berlin Wall” for largely insulating Nixon from having to deal with staff squabbles.18 In addition to “the two Germans,” Attorney General John Mitchell, Nixon’s former law partner and campaign chief, was another central player in smoothing ruffled feathers within the administration.19

When Nixon ordered Kissinger to handle discussions with the Soviets on a possible Middle East settlement in the summer of 1971, he willfully excluded Rogers from the loop and fueled a Kissinger-Rogers flare-up. Likely sensing a stall and backroom maneuvering by his bureaucratic nemesis, Kissinger, Rogers forced the issue by calling Haldeman at home on January 16, 1972. However, Rogers’s gambit failed when Nixon dispatched Haldeman and Mitchell to develop a solution. Haldeman reported back to Nixon that Rogers had argued: “The theory here is that the president has announced his policy. State Department carries it out. The NSC is not supposed to be in operations, it’s supposed to be a policy group.” As for the Middle East discussions, Rogers told Haldeman, “[T]he NSC is not involved in the Mid East…. I am handling that. We’ve been doing it for three years and it’s worked very well.”20 Instead of reaffirming Rogers’s Middle East role, Nixon chastised the secretary’s outmoded thinking about the role of the State Department, and he softened the blow to Rogers in a letter drafted by Haldeman.21 Had not Kissinger’s secret July 1971 trip to China and ongoing negotiations with the North Vietnamese hammered the point home to Rogers that the NSC, and its chief, were, in fact, “in operations”?

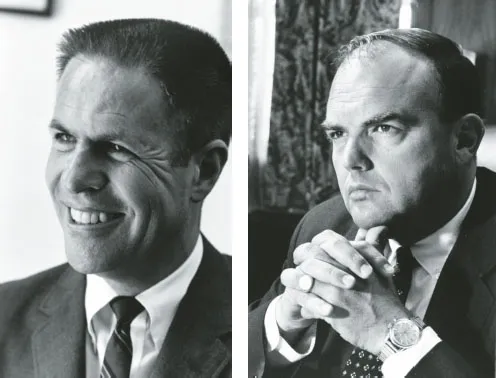

Nixon’s chief of staff, H. R. “Bob” Haldeman (above left), and chief domestic advisor, John Ehrlichman (above right). With their Teutonic-sounding names, Haldeman and Ehrlichman were known as “the two Germans” and also as the “Berlin Wall” for largely insulating Nixon from having to deal with staff squabbles. (RNPLM)

Bureaucratic maneuvering aside, back-channel diplomacy had other functions. Despite their different backgrounds, Nixon and Kissinger shared similar beliefs about the pursuit of national interests, the dangers of the thermonuclear age, and a philosophy of secrecy. Both men gravitated to the use of back channels. As Nixon scholar Joan Hoff, a proponent of the “Nixinger” foreign policy, has noted: “Both relished covert activity and liked making unilateral decisions; both distrusted bureaucracies; both resented any attempt by Congress to interfere with initiatives; and both agreed that the United States could impose order and stability on the world only if the White House controlled policy by appearing conciliatory but acting tough.”22 Back channels allowed public and private messages to diverge and provided a potential silver bullet to avoid the issue of leaks and the press.

Like the State Department, the Foreign Service, the amoebic “bureaucracy,” academics, and the “Eastern Establishment,” the Fourth Estate could not be trusted, Nixon believed. His enemies, perceived and real, could be fought with secrecy, and public opinion could be shaped or altogether circumvented by timely breakthroughs and bold plays concealed by confidential moves.23 At one point, Nixon admonished Kissinger, “Now, Henry, remember, we’re gonna be around to outlive our enemies.” In a low voice, Nixon added: “And, also, never forget: The press is the enemy. The press is the enemy. The press is the enemy. The Establishment is the enemy. The professors are the enemy…. Write that on a blackboard a hundred times and never forget it.”24 Without resorting to armchair psychology, as seems fashionable in several biographies that have labeled Nixon paranoid or neurotic, it is worth noting that once in power, the Nixon administration had some reason to be suspicious.25

In a vicious and destructive cycle, leaks by officials of highly classified documents confirmed Nixon’s hatred of the press, exacerbated his fears, and reaffirmed the use of back channels to shelter sensitive negotiations. Leaks about arms control efforts started two weeks into the administration as Nixon was caught off guard at a press conference on February 6, 1969—less than a month in office—by the revelation that Secretary of Defense Melvin Laird had halted the deployment of the Sentinel Anti-Ballistic Missile system. Laird had not discussed the matter at the NSC, according to Haldeman, and the facts had not been included in Nixon’s briefing material.26 In the first year, leaks continued with materials from high-level meetings about troop withdrawals from Vietnam, the reversion of Okinawa to Japan, the secret bombing of Cambodia, and even internal deliberations about Supreme Court nominations appearing in the press. Early in the administration, Kissinger endorsed wiretaps on NSC staffers and journalists to try to discover the sources of leaks.27 The leaks only increased, and the administration took more active measures in response.

In June 1971, the New York Times began to publish excerpts from the Pentagon Papers, a top-secret study commissioned in 1967 by then secretary of defense Robert McNamara. The study documented American involvement in Vietnam from 1945 to 1967—before Nixon became president. Initially, Nixon reacted to the news calmly, but after consulting with Kissinger and Attorney General John Mitchell, he decided to pursue legal action against the Times to block further publication.28 White House aides Egil “Bud” Krogh and David Young proposed the formation of the White House Special Investigative Unit to ferret out and stop the disclosures. The so-called Plumbers became entangled with the Committee to Re-Elect the president (CRP, or CREEP), and its illegal activities became the foundation of the “abuse of government power” charges brought against the president and a number of his top aides by 1974. Nevertheless, there were legitimate national security considerations behind the activities, at least initially.

Part of the rationale behind the Plumbers was to protect back channels. In 1995, Kissinger told journalist and author James Rosen, “We felt that if the government didn’t protect its secrets, the whole apparatus would be in danger.” Rosen explained, “The ...