![]()

1

On Jordan’s Banks

The Origins of Community, Faith, and Struggle in Cairo

The black church has historically served as a key staging ground for black freedom struggles in Cairo, Illinois. At crucial junctures throughout the city’s history, social movement organizations have relied on black churches for their extensive organizational and ideational resources. In turn, local congregations opened their doors and extended their hands in support of struggles for rights, respect, and empowerment. By the late 1960s the city’s black churches had a strong legacy of protest and occupied a position of social and cultural preeminence that grassroots activists were forced to navigate in their attempts to build effective movements for racial change and social justice. However, the black church’s centrality to local protest traditions was neither inevitable nor complete but rather contingent on three interrelated factors: the distinctive social and political conditions of black life in the northern borderland; the relative homogeneity of black religious traditions; and the agency and skill of activists responsible for recruiting congregations into the movement.

In this chapter I trace the broad contours of black life and community in Cairo, Illinois, across four overlapping historical periods, showing how the city’s economic instability and distinctive blend of northern and southern racial practices combined to ensure the black church’s emergence as the central institution in black community building and protest traditions. More specifically, I argue that the consignment of black Cairoites to the lowest rungs of the river city’s declining economy hindered the development of a proletarianized black working class and attendant black middle class capable of sustaining autonomous institutions that might have rivaled the church’s role in the black community. Further, political reforms passed during the early twentieth century undercut the ward-based electoral power of black voters, putting an end to an era of black officeholding and patronage. Pushed to the margins of formal political institutions, black Cairoites increasingly looked to the church as a site of political protest and social movement activity.

In turn, I demonstrate that the rise of Cairo’s black churches to a position of political and cultural preeminence was also facilitated by the specific quality of the religious tradition they harbored. In contrast to many larger cosmopolitan midwestern cities, post-Civil War Cairo was bypassed by the new waves of migration and industrial expansion that elsewhere contributed to a diversification of African American faith traditions or to secularization. In contrast, Cairo, like other borderland cities, maintained a comparatively strong and homogenous religious culture rooted firmly in the evangelical Methodist and Baptist traditions. This unifying religious culture provided an important institutional basis for racial solidarity and ecumenical organizing upon which local activists would capitalize in their efforts to build viable black freedom struggles.

Way Down in Egypt Land (1818–1861)

At the dawn of the nineteenth century, a small patch of cypress-filled swampland at the confluence of America’s two great waterways—the Ohio and the Mississippi—captured the interest of the new nation, North and South. Strategically located in the newly incorporated Illinois Territory on the westernmost front of the nascent American empire, these muddy bottomlands drew expeditionary forces, fur trappers, merchants, and eventually eastern speculators seeking to profit from the river traffic central to the burgeoning market revolution of the new century. Profiteers were aided in their endeavors by the encroachment of Euro-American migrants and squatters from the Upland South. They were also abetted by treaties signed with the five tribes of the Illinois Confederacy in 1803 and 1818, which resulted in the ceding of the tribes’ remaining land rights, paving the way for statehood and public land sales.1

Despite this convergence of waters and events, efforts to capitalize on the site’s position at the confluence were punctuated by a series of failures. Virginia planter and slaveholder Abraham Bird was among the first to observe the site’s potential while setting up camp at the confluence on a journey to Cape Girardeau in 1795. Though Bird departed shortly after for the sugar plantations of Louisiana, his sons William and Thompson Bird expanded the family’s mercantile interests to the confluence in July 1817, purchasing 318 acres in the southernmost part of the contemporary city of Cairo. On the same day that the southern planters staked their claim, an ambitious group of eastern speculators headed by the Baltimore merchant John Comegys incorporated the City and Bank Company of Cairo and purchased a larger 1,800-acre tract just north of the Birds’ holdings. Envisioning a great river metropolis, Comegys and his compatriots solicited sponsorship from European financiers. However, within a few short months the project collapsed and the land defaulted back to the territorial legislature. Accordingly, it fell to the Birds’ enslaved African laborers to erect the first-known permanent structures at the confluence, consisting of a waterfront tavern and store that drew the trade of flatboat and steamer crews charged with transporting cotton, sugar, rice, and human cargo.2

When British novelist Charles Dickens arrived at the confluence on the steamboat Fulton in 1842, he was anxious to see the town “vaunted in England as a mine of Golden Hope,” but he was horrified to discover what he would record in his travelogue American Notes (1842) as little more than “a dismal swamp,” “a detestable morass,” and “an ugly sepulcher . . . uncheered by any gleam of promise.” Cairo, which the writer parodied as “Eden” in his subsequent novel Martin Chuzzlewit (1843), was to Dickens the archetypal nineteenth-century “paper town” designed to appeal to distant speculators by way of “monstrous representations” that falsely portrayed a bustling river city populated by factories, hotels, and public buildings.3 In the five years preceding Dickens’s sojourn, London-based investment bankers Wright & Company had sponsored a second attempt to develop the site. In 1837 Boston merchant Darius Holbrook secured a charter aimed at transforming Cairo into a “great commercial and manufacturing mart and emporium”; using capital from Wright & Company, the newly incorporated Cairo City and Canal Company oversaw the clearing of land and construction of levees. However, Holbrook’s company failed during the depression of the late 1830s, prompting an exodus of workers and a collapse in foreign investment. When Dickens arrived just a few years later he found Cairo largely abandoned; only a score of impoverished squatters remained. Desperate to recoup their losses, several of the original speculators formed the Cairo Property Trust and in 1852 secured Cairo’s bid to become the southern terminus for the Illinois Central Railroad (ICR), marking a key juncture in the community’s fortunes and development.4

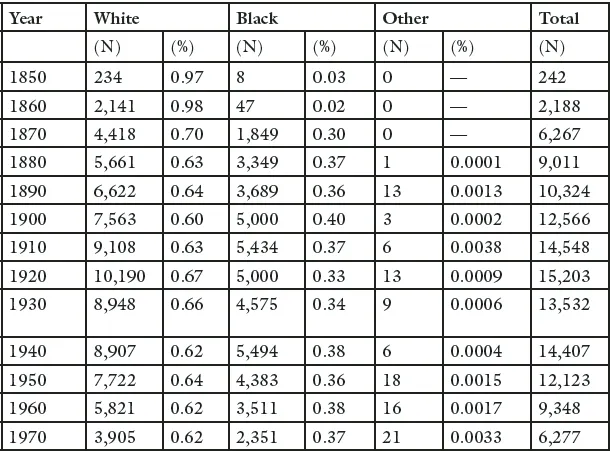

In the decade that followed, Cairo would emerge as Southern Illinois’s largest city and an important midwestern transshipment hub focused on the storage, processing, and transportation of staple crops, consumer goods, and enslaved workers. In 1854 the number of boats landing in Cairo totaled 3,798, surpassing nearby St. Louis, which received 3,006 vessels that same year. After the completion of the ICR in 1854, Cairo dockworkers loaded cargo directly from riverboats onto railroad cars heading northward. The commodities that they carried—molasses, sugar, wool, and cotton—reveal Cairo’s dependence on the southern plantation economy as well as its role as a gateway to northern and eastern markets.5This unique interstitial position afforded Cairo what one scholar of the borderland has defined as “a dual personality,” reflective of both northern and southern traditions.6 In addition to the burgeoning river and rail trade, antebellum Cairo maintained a number of small industries, including lumber mills, ironworks, brickworks, and flour mills. The city’s commercial expansion resulted in renewed migration, growing the population from 242 in 1850 to 2,188 just ten years later (see table 1.1). Initially populated by rural white migrants from the Upland South, Cairo—like many other borderland communities—began to attract northeastern artisanal families as well as significant numbers of German and Irish immigrants who transformed the cultural landscape by establishing their own institutions, including foreign-language newspapers, beer gardens, sports clubs, literary societies, and churches. Initially, the city’s Catholic population attended St. Patrick’s Church, founded in 1838. However, in 1872 the construction of St. Joseph’s Church afforded German immigrants their own edifice. Parochial schooling was also established along ethnic lines; Irish immigrants attended St. Patrick’s parochial school and German immigrants St. Joseph’s.7

In contrast, Cairo’s African American population remained comparatively small due to Illinois’s status as a “quasi-slave state” and rigorous enforcement of both the Fugitive Slave Act (1850) and black exclusion laws (1853). Though the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 barred the importation of enslaved workers into the territory, human bondage persisted in the southernmost parts of Illinois, Ohio, and Delaware in a variety of de jure and de facto guises. After statehood in 1818 more than one thousand black Illinoisans remained enslaved under a complex legal framework: longstanding protections of the property rights of slaveholders of French descent were combined with indentured servitude and special provisions for the leasing of enslaved workers at the United States Saline works in Shawneetown. In contrast to their southern counterparts, the majority of those enslaved labored in domestic or industrial capacities, not in the production of cash crops. However, even in the absence of the plantation system of agriculture that typified the political economy of communities farther south, support for racial slavery among Egypt’s pro-southern Democrat elite was strong, prompting a failed attempt in 1824 to secure a constitutional convention permitting the ownership of chattel property. As state laws governing indenture and enslavement gradually tightened, some Alexander County slaveholders (like the Birds) shuttled their workers back and forth across the Mississippi River to Missouri in an effort to secure their property rights as Missouri citizens. Others, like Alexander County state representative Henry Livingston Webb, simply kept their indentured servants illegally. Accordingly, the earliest black Cairoites arrived as forced laborers or manumitted slaves and entered a northern borderland community where their rights were ambiguously defined and almost always unprotected.8

Egypt’s contiguity to Missouri and Kentucky’s slave-rich Jackson Purchase region raised the specter of runaway slaves and free black refugees. White opposition to black migration constrained the growth of the black population across the northern borderland and rendered African Americans vulnerable to acts of racial violence as well as to capture and sale into slavery.9 Most free blacks moved to urban areas to build communities that could afford some degree of protection. In the decade preceding the Civil War, black Cairoites lived in close proximity to each other in several large augmented households reflective of what Sundiata Cha-Jua has described as the “adaptive extended kinship networks” of black Illinoisans during this period. Cairo’s African American households often included nuclear and extended kin as well as nonrelatives. James and Maria Renfrow, a young married couple who moved to Cairo during its ascension in the 1850s, lived alongside domestic laborers Mary Head and Agga Maddox. Similarly, Andrew and Susan Mills shared their home with washerwoman Mary Posey, steward James Gale, and housekeeper Sara Wilson. By taking in boarders, families like the Renfrows and Mills fostered a culture of mutuality designed to weather the effects of Cairo’s racially stratified labor market.10

Consigned to the lowest paid menial positions as domestic and personal servants, black Cairoites possessed little property. The wealthiest household in 1860 was headed by twenty-five-year-old cook George Williams, who amassed a fortune of just two hundred dollars. Augmented households also reflected the distinctive cultural heritage of Cairo’s black residents, many of whom had recently escaped bondage and now lived in a tenuous borderland between North and South. Some, including forty-year-old Jane Robinson, opened their homes to manumitted slaves like Jane Baker, who had recently received her freedom papers from the Cook family in Alexander County. Others, like Malinda Harville, risked their own freedom by harboring runaways fleeing across the two rivers. Harville reportedly took in a man named Joseph who in August 1855 absconded from the plantation of Thomas Rodney in Mississippi County, Missouri. Harville purchased train tickets for Joseph to Chicago, an act for which she was punished by local whites, who burned her home to the ground. However, the city’s railroads and steamers continued to function as important avenues for underground railroad activity led by free blacks like Harville and George J. L. Burroughs, a Canadian sleeping car porter who claimed to have smuggled many stowaways from Cairo to Chicago in the years preceding the Civil War.11

The precariousness of black Cairoites’ freedom no doubt solidified these bonds with their enslaved brethren just across the river. The Illinois Black Codes barred black residents from voting, assembling in large numbers, and serving on the state militia, while local customs excluded them from the city’s schools and the Catholic parishes. Even worse, free blacks in Cairo lived under the ever-present threat of kidnap and sale into slavery with no recourse to the courts. In July 1857 these growing tensions erupted when kidnappers descended on the home of two free black men, beating them and forcibly transporting them across the river into Missouri to be sold into slavery. One of the men, though “horribly mangled about the head,” was able to escape and swam back across the Mississippi River to Cairo.12 A few days later a gang of Missouri slave catchers arrived in Cairo pretending to look for runaways and launched an assault on the black settlement. Free blacks took up arms against the gang, shooting one white man in the face. Fearing for their lives, Cairo’s black residents fled to Mound City in neighboring Pulaski County. Such events garnered little sympathy from local whites, who frequently complained that the very presence of free blacks in the city constituted a direct violation of the state’s black exclusion law, which 98 percent of Alexander County voters had supported in 1848. To stave off vigilantism, local officials formed posses in the 1850s and arrested black residents under the antisettlement law. Despite these dangers, African Americans continued to migrate to Cairo and the black population rebounded to 47 in the three years after the 1857 exodus (see table 1.1). With the limited resources they possessed, the new migrants strove to develop their own institutions, including a small private school that charged a fee of one dollar per month to the city’s wealthier black families. However, broader efforts in community and institution building would await the Civil War and the vast migration of enslaved African American men, women, and children across the Ohio River.13

Table 1.1. Population of Cairo by Race, 1850–1970

Crossing Over to Canaan Land (1861–1890)

On the muddy banks of the Ohio River, men sit hunched over, staring out across the waters, their hands resting on their knees. Nearby, women in headscarves and cheap linen dresses pull their children close as Union soldiers mill around, perhaps taking down the names of the sundry passengers recently disembarked from a nearby steamer. These scenes depicted in Sophie Wessel’s 1963 painting Contraband on Cairo Levee capture the ...