- 358 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

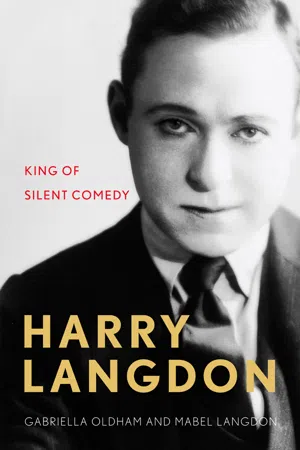

Yes, you can access Harry Langdon by Gabriella Oldham,Mabel Langdon in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Film History & Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Vaudeville Roots

By the time his second son was born, William Wiley Langdon from Clinton, Missouri, had nearly given up his wanderlust. William had roamed the American Midwest, working as a sign painter, until he met and married Illinois girl Lavinia Lookingbill.1 William and Lavinia resided in Illinois and Wisconsin before eventually settling among the 30,000 inhabitants of Council Bluffs, Iowa, sometime in the early 1880s. They had already started their family: first came John, and then a year later, on June 15, 1884, Harry Philmore Langdon was born.

Council Bluffs might have appealed to William for its business potential. On the east bank of the Missouri River and directly across from Omaha, Nebraska, Council Bluffs had become a thriving hub with the expansion of the railroads in the late 1860s and early 1870s. It was said that Abraham Lincoln had selected a spot on Lafayette Avenue in Council Bluffs as the eastern terminus of the transcontinental railroad.2

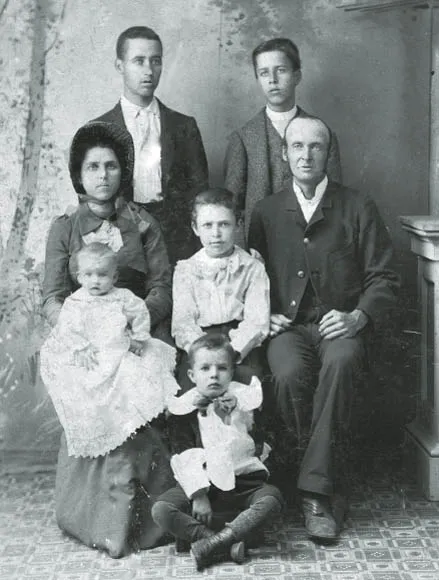

Even though he settled in Council Bluffs, William never lost the urge to keep moving. He and Lavinia and their brood of five boys (John, Harry, James, Charles, and Claude) and one girl (Gertrude) replanted themselves in several different neighborhoods within the town.3 They bought a small house on East Pierce Street in 1885, moved not far away to Vine Street for about a year in 1889, and then relocated again to Harrison Street in 1891. Harry attended elementary school—the extent of his education—when the Langdons resided in the Avenue B school district. In 1894 the family lived in a more centrally located apartment on West Broadway, from which little Harry could more easily ride the streetcar across the bridge into Omaha. There, big-city life and the theater were far more captivating to Harry than working in the family business as a painter.

William had established a painting business with his brothers. The Council Bluffs directories from 1882 to 1922 listed W. W. Langdon as a house and sign painter. He was joined throughout the years by sons Charles in 1893, John four years later, and Claude in 1910. Girls were clearly not part of the family business and settled for more feminine occupations: the name of baby sister Gertrude first appeared in the records in 1914 as a music teacher. James, whose lifelong nickname was Tully, was variously listed as a painter for his father and as a clerk, a cutter, and a butcher at the local Keeline and Pace stores. In 1912 Tully was finally listed as an “actor”—a startling divergence from the family occupation. This was no doubt thanks to his older brother’s burgeoning influence; while nearly every other Langdon male was painting or paperhanging, Harry was escaping to the theatrical world whenever he could. Harry’s name appeared in the records only once—in 1901 as a painter, a temporary and likely reluctant hiatus while in between theatrical jobs on the road. The next time Harry’s name appeared in the directory was in 1913 as an “actor,” and so it remained for all subsequent entries—and for the rest of his life after leaving Council Bluffs.

As William built his family business, Lavinia—typically listed as a “housekeeper” in census records—tried to keep her children in line, and Harry seemed to be the only outlier in the group. William was reputedly not very religious, but Lavinia was a devoted member of the Salvation Army, a Christian group dedicated to following the Scriptures and serving humanity to bring them closer to God’s salvation.4 In 1865 William Booth and his wife had founded the Salvation Army in London, basing it on a military model with ranking officials, uniforms, and flags and with a mission of serving as “soldiers” in God’s army.5 Their mission of providing “soup, soap, and salvation” to those in need spread to the United States in 1880, initially in Philadelphia and then outward across the country. A Council Bluffs corps of the Salvation Army opened in October 1886, closed in November 1911, and later reopened in April 1920. Although none of the Langdons served as officers, Lavinia—and as many of her children as she could persuade—must have regularly congregated at various locations along East Broadway for Sunday services, which were often held both morning and night. They likely participated in midweek prayer meetings and the open-air meetings or marches for which the Salvation Army was noted. Especially at Christmas, family dinners were offered, along with activities for children. In 1893 one meeting site was Dohany’s Opera House at 15 Bryant Street, an amazing coincidence for Harry, who had discovered the theater as a refuge from his mundane life. Built on the site of Palmer’s Concert Hall, which had been destroyed by fire, the Dohany was dedicated in 1882 and had a seating capacity of 1,400, which must have made it an inspiring venue for Salvation Army meetings. When it was not hosting weekly prayer ensembles, the Dohany offered lively vaudeville programs with ventriloquists, singers, dancers, comedians, dancing animals, and novelty acts. The audiences were often both appreciative and rambunctious in their criticism.6

Most of the Langdon family in Council Bluffs, Iowa. Clockwise from left: baby Gertrude, Lavinia, Charles, John, William, and James, with Harry in the center.

Harry found the theater far more fascinating than either the classroom or business. For him, nothing could compare to the music and makeup, the flickering stage lights, and the applause. All of it touched Harry’s artistic sensibilities at a tender age. He was already exploring his musical talent, a gift that Lavinia claimed came from his uncle Isaac, who would have made a great church musician if he had not wasted his talent playing the piano in saloons and being shot to death in a drunken brawl. Harry tinkered with the banjo, piano, trumpet, and other wind instruments and was sneaking into the Dohany to see the shows—and just as quickly being ousted as a pest. It is touching to imagine that, at least briefly, the Dohany would be both inspiration and aspiration for young Harry. There, he witnessed his deeply religious mother’s model of spiritual strength, even if the extent of his own participation was rattling a tambourine to accompany the robust singing of hymns. But he was also absorbed in the theater’s colorful representations of entertainment and the thrill of public recognition. These possibilities fed his young spirit, which refused to be boxed into a traditional job. Both aspects of Harry’s life at the Dohany would continue to influence his childhood years and direct his future.

As a remarkably sensible eight-year-old, however, Harry realized he could not achieve the spotlight right away. He resigned himself to delivering the Omaha Bee in a residential neighborhood, sometimes selling newspapers all day and sleeping in the press room at night. Still, this was monotony for a boy whose fantasies were activated simply by passing the theater. His large family could not afford to indulge in the social extravagance of actually attending a performance (nor would his religious mother have approved of a show-business life, which upstanding citizens generally regarded as scandalous and immoral). To help at home, Harry dutifully rode across the river to Omaha, peddled his papers, and contributed his earnings to the household. To amuse himself between filial obligations, Harry discovered a talent for drawing caricatures. Staff at the newspaper’s editorial offices praised his work, and Harry even sold an occasional cartoon to the Bee.

Two years later, when his delivery route was switched to include the downtown section where the Dohany stood tall and proud, ten-year-old Harry would dart into the showplace at the end of his workday and study the vaudeville programs. He attended so frequently that he memorized some of the skits and performed them, to the delight of his neighborhood pals. In an interview for the French weekly Mon Ciné in 1925, Harry (a new movie star at the time) reminisced that he had built an impromptu theater out of old planks, crates, and curtains in his father’s backyard and provided entertainment to the local kids, initially for free and then for “money”—meaning beads and candy sticks. His production, entitled “The Grand Theatre of the World, and Omaha,” was lavishly designed, at least from a child’s-eye view. Harry had assembled fruit boxes to create a suit of medieval armor and charmed his way through multiple long monologues—primarily because he was the only actor available. He began to sense the power that came from being his own director, producer, and writer. The adoring accolades of his young, naïve audience only fueled his desire for more.7

Harry also recruited his brother Tully and taught him the choreography he had learned through observation, including a song culminating in a fancy split. To raise more “funds” for his home productions, Harry brought Tully to a local restaurant, stood in the doorway, and asked whether the diners wanted to see some live entertainment. Given the evident determination of the two boys, the diners usually agreed to the performance. Harry then accompanied Tully on the mouth harp to a song-and-dance routine capped off by the well-rehearsed split. The coins Harry collected from the diners formed the basis of what he called the “company treasury.”8

While Lavinia wondered what had possessed her wayward son, William was often less than pleased with Harry’s homespun theatrical pursuits. One day, in an effort to construct a vehicle intended to be a train, Harry used a barrel for the wheels, affixed a coal oil bucket to serve as the funnel, and then deposited William’s celluloid collars into the bucket and set them on fire to supply the necessary smoke. Then, hiding “offstage” in the “wings” of his performance space, Harry pulled the barrel along by a rope to create a rolling locomotive effect. While the neighborhood kids marveled at the illusion, William was furious that his personal possessions had become disposable props for this foolhardy spectacle. Harry found he could not sit for quite a while after his father expressed his disapproval of the act.

Despite their concern over the behavior of their precocious offspring, William and Lavinia considered Harry special. According to family lore, they had almost lost him when, at a very young age, Harry suffered a terrible disease (likely diphtheria) that closed his throat, leading the doctor to tell them there was no hope of survival. A grief-stricken William sat on the front porch just as the local veterinarian rode by and asked what was wrong. The veterinarian advised William not to give up and directed him to fill a tub with water and lye in the barn. Over Lavinia’s objections, the two men carried the ailing Harry in a sheet and rocked him over the tub so that he could inhale the dreadful fumes rising from the brew. Miraculously, Harry’s throat opened and he could breathe freely again, but the fumes also damaged his vocal cords, leaving him with a voice that was higher than normal. Whatever the cause of this vocal quality, Langdon’s voice later had both positive and negative effects on his stage and film work.9

Harry’s parents knew they would eventually lose their son—if not to illness, then to the theater. So they resigned themselves to the likelihood that Harry would not carry on the family business with his brothers. Harry, however, never doubted his “calling.” Passionately stagestruck, he found personal fulfillment at the theater that nothing else offered. He had no personal friendships that bound him to home or school (which he barely attended). The neighborhood kids were useful primarily as an enthusiastic audience, and they no doubt looked forward to Harry’s exciting stories. He was a one-man show, re-creating the world on his miniature stage. He was always on the hunt for the next adventure that would take him beyond his boundaries. Others around him may have had fantastic aspirations, but Harry was the only one among his family and friends who made them real. It was neither bravery nor daring: for Harry, it was a natural instinct and an impulse he had to follow.

Not even his pet duck, which followed him everywhere, could hold Harry back when the theater beckoned. William knew Harry had fled to some theatrical daydream when he spotted the duck wandering through the streets searching for his companion. William would then set off to drag Harry away from the Dohany and back home. This occurred frequently because, when left to his own devices, Harry would even forget to come home for dinner. When mealtime passed and Harry’s seat at the dinner table remained vacant, his parents knew they would find him in the backstage corner of the Dohany. In 1896 tickets cost ten to thirty cents, and whenever Harry could afford the price of admission, every cent was worth the sacrifice.

Harry wasted no time finding jobs in the theater and was amenable to being a ticket taker, usher, prop boy, cashier, call boy, sign painter, or even painter of footprints on the sidewalk, used to entice patrons to walk into the “opry house.” At such times, Harry no doubt thanked his father, at least mentally, for exposing him to the painting business. At night, Harry steadfastly memorized the parts of both lead actors and bit players.

Like many theaters of the day, the Dohany featured amateur nights, which allowed the management to save money by not having to pay for professional entertainment. Proud relatives welcomed the opportunity to cheer their gifted offspring and boo the competition. One Friday, on his first amateur night, Harry was introduced to the actual experience of stage acting—and stage fright—in front of a paying audience.

Obviously impressed with his flair for imitation, the manager of the Dohany asked Harry to be the house entry at next Friday’s amateur show. Although Harry’s act was not polished, the manager felt assured of getting a halfway decent performance. Harry practiced his song-and-dance number in front of a mirror at home, and his performance onstage—a combination of innate talent and unintentional comic mistakes caused by nervousness—won him enthusiastic applause and laughter. In later years, Langdon spoke of feeling like a “successful flop” as he stumbled through his song-and-dance set. The stage director and the manager, however, convinced Harry that he had been the hit of the show. They may have thought Harry’s “stardom” would never go beyond the amateur stage, but he was perfect for their purposes, and they encouraged him to continue performing. He persevered, motivated perhaps by the dream of being a star one day. Harry eventually won an assortment of prizes, including canaries, cut-glass bowls, and goldfish. His family once boasted that, thanks to Harry, they had six large clocks for their parlor.

Harry, now twelve years old, no doubt believed that show business was his destiny. So when the Kickapoo Indian Medicine Show visited Council Bluffs, it left with a new member. The spectacle of “Natives” in full regalia and quick-talking salesmen peddling miraculous nostrums convinced Harry to join without delay. The Kickapoo show was the brainchild of John E. Healy and his partner Charles F. Bigelow in the late 1880s. They devised the idea of touring with a show that exhibited Indian life and “authentic” members of the Kickapoo tribe (their winter residence was a “wigwam” in New Haven, Connecticut). In bottles, tins, and boxes depicting Wild West–style Indians in feathered and beaded garb, the company sold “all-natural medicines”—oils, tonics, pills, salves, and soaps that cured everything from coughs, chills, fevers, piles, ulcers, worms, and cancers to digestive and kidney irregularities. The roster of natural ingredients, meant to impress ailing clients and persuade them to part with their dollars, included licorice, dandelion, burdock root, aloe, horehound, cloves, camphor, myrrh, and sassafras. Mother Nature was sometimes assisted by a 60 percent alcohol content.10

Trouper that he was, Harry hawked the medicine, engaged in rigged fights, sang and danced, and did whatever his boss—a tough type by the name of “Dutch” Schultz—told him to do. He pitched tents, slept in a trunk, and filled medicine bottles in secluded spots or hotel rooms, out of sight of the gullible small-town residents. Ignoring the obvious huckstering that was a big component of the medicine show, Harry enjoyed providing comedy ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Foreword

- Introduction

- 1. Vaudeville Roots

- 2. Golden Silence

- 3. Elusive Stardom

- 4. The Stronger Man

- 5. Legacy

- Acknowledgments

- Filmography

- Notes

- Selected Bibliography

- Index