eBook - ePub

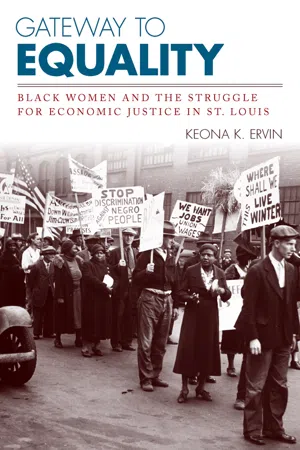

Gateway to Equality

Black Women and the Struggle for Economic Justice in St. Louis

- 294 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Gateway to Equality by Keona K. Ervin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Women in History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

The University Press of KentuckyYear

2017Print ISBN

9780813177540, 9780813168838eBook ISBN

97808131698661

“We Strike and Win”

Food Factory Workers and Labor Radicalism

The nut shellers who toiled in one of the five factories owned and operated by the R. E. Funsten Nut Company entered the shop floor on Monday, May 15, 1933, as they always had, but this day did not follow the normal routine. That morning, Carrie Smith, an eighteen-year veteran at the company, initiated a strike at the plant, informing her colleagues that workers at Funsten’s shop on Easton Avenue had planned to strike at 7:30 a.m. and that colleagues in her own shop would do so thirty minutes later. The plan was to whistle when the time had come. Smith announced, “The heavy stuff’s here! Get your hats and coats and let’s go”; the first part of the phrase was code for workers to stop production. Smith confronted a foreman on her way out to make sure that her colleagues would have no problems with exiting the shop floor. The strikers marched to a nearby park, where they elected Smith chairman and chose ten additional participants to serve on the strike committee. Smith and a colleague confronted their boss, talking for two hours. When they failed to get an agreement to raise wages, the two representatives joined the strikers and made plans to meet with Mayor Bernard F. Dickmann the following morning.1

Tapping the organizational apparatuses of community institutions and radical labor unions, black women domestic and industrial workers fashioned a militant worker rights struggle forged out of their particular economic experiences. An outgrowth and extension of the Communist Party’s unemployed rights movement, the Funsten Nut Strike marked black women’s attempt to recoup losses in pay, put an end to the mistreatment they suffered on a regular basis, and implicate the state in the marginalizing effects of industrial capitalism. Women workers reached their tipping point when, between 1931 and 1933, they succumbed to a series of five wage cuts. With backing from the Communist Party and its Food Workers Industrial Union, a majority of African American women and a minority of immigrant ethnic women waged a workplace struggle that turned into a general eight-day work stoppage with more than one thousand participating. Through militant mass action, nut shellers claimed that as members of the industrial working class, they deserved a living wage. Existing analyses of the strike point out how the insurgency marked a fresh brand of worker self-organization, reflective of early 1930s radical trade unionism, which galvanized communities and connected workers’ living concerns to the workplace. Others establish black working-class women’s radical economic politics within the scope of a broader working-class movement for racial justice in the border South. This strike was a pivotal moment in the history of Gateway City labor radicalism, in which questions of black women’s survival found center stage.2

The nut pickers’ strike was St. Louis’s most significant economic rights battle during the early 1930s. Newspapers in and outside of the Gateway City covered the episode, prominent local leaders weighed in or became involved, and the Communist Party USA (CPUSA) used the strike as a moment to mark the urban Midwest as a new hotbed of radical labor politics spearheaded by black working women. The nut pickers’ strike was among the most important labor battles of its time for three main reasons.

Most importantly, the strike established black working-class women as central actors in the battle for workers’ rights. Black working-class women formed the majority of the leadership and the rank and file; they were the face of the struggle. They effectively politicized their status as marginal wage workers at the intersection of struggles for economic, racial, and gender justice. At heart, their struggle carved out space for black working-class women within industrial labor, which was viewed by most people as the exclusive or near-exclusive domain of white men. Relatedly, the strike brought visibility to black working-class women’s economic experiences and raised their visibility as political subjects. Carrie Smith and Cora Lewis, along with a thousand others who joined them, drew attention to their status as workers whose wages made black women’s survival possible. Their labor benefited their families and communities, and it bridged workplace and community along with aiding the struggle for economic justice and racial equality.

Second, the strike helped strengthen the organizational infrastructure of radical unionism and set the stage for an emerging wave of progressive and radical workers’ rights struggles as workers in the electric and automobile industries and workers in garment industries, for example, followed suit by engaging in their own work stoppages. Black working-class women’s campaign for better wages performed essential work for progressive and radical organizations that operated at the local level. The strike extended the influence of the radical left’s unemployed rights’ struggle into the arena of industrial work, connecting industrial workers and the unemployed within the same political framework. It also helped the CPUSA maintain its influence within the labor movement and extend its credibility and distinctiveness through adoption of an antiracist platform that made space for black working-class women’s political leadership. In addition to assisting the local left, strikers and members of the newly formed union connected liberal social reformers, radicals, and municipal leaders, forcing them to consider the causes and contexts of working women’s economic experiences. The community-based approach deployed by the nut pickers, along with their commitment to build solidarity across the color line and among those who performed so-called unskilled labor, laid the groundwork for the emergence of progressive unionism, most powerfully practiced by union members of the nascent Congress of Industrial Organizations. Unionists found relative success by adopting the practices of the nut pickers. Black working-class women’s social activism broadened and deepened the economic justice struggle in St. Louis.

Finally, the nut pickers’ story, a mix of poverty tales and labor’s public expression of its deep disgust, captured the promise and limits that the 1930s brought to the ordinary worker. The labor struggle exemplified the political culmination of worker discontent and disaffection that came to define 1930s politics. It provided St. Louisans with its “instance right at home.” “Some future social historian, writing on the country’s plight in 1933,” an editorialist for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch opined, “may well view as a significant phenomenon of our times that 1200 adult woman workers in St. Louis went on strike against a wage scale of 50 cents and less a day, and won terms that were expected to double their pay.” The nut pickers’ case became symbolic of the conditions that had come to define industrial capitalism and a model of the power of workers’ self-organization. Women like Cora Lewis and Carrie Smith symbolized the beleaguered American worker across race and gender.3

Nut shellers, the more militant faction of nut pickers’ working-class sisters, were a marginal group among those deemed the leaders of black politics, who ranged from heads of social service agencies and advocacy groups to black clergy and black municipal officials. Unlike domestic workers, nut pickers were beyond the scope of legible black female political subjectivity within certain influential and powerful arenas in their own racial community; their story suggests that the ability of this particular subgroup of black working-class women to gain access to political subjectivity depended on the possibility of seizing coalition-building opportunities with groups outside their racial circle. Nut pickers confronted marginalization and political misapprehension. Out of their social marginality, they forged interracial working-class solidarities with the CPUSA, which had also encountered social marginalization among established political and social leaders because of its radicalism. A range of figures with a stake in the strike’s outcome carried misguided notions. Some believed that the nut pickers were dupes of the CPUSA, not an uncommon accusation used to delegitimate black progressive and radical politics; others thought they were outside of the respectable black female working class; while still others, including the nut pickers’ staunchest supporters, believed that black working women lacked political savvy and finesse. The labor struggles of nut pickers, in particular, expose the gap between black working-class women’s marginalization and misapprehension and their own conceptualization of their politics. The gap suggests that among black working-class women, nut pickers uniquely labored to dispute ideas about who embodied the cutting edge of working-class struggle.

“A Shadow of Racism in It”: The Nut-Picking Industry

The black women who toiled in the nut shelling factories that were scattered across the St. Louis metropolitan region labored under segregated arrangements and in deplorable conditions. Trapped in a factory management system that privileged employees of a lighter hue, black women worked longer hours, earned less money, and performed more arduous work than the immigrant women of Polish descent who joined them. Black women earned just three to four cents per pound of shelled nuts, compared to the four to six cents that immigrant women earned—a 30 percent to 40 percent difference. In the basements where they worked, black women nut pickers separated nutmeats from their shells, an act requiring dexterity and causing physical strain; by contrast, immigrant women performed the preferred work of sorting and weighing half and whole pieces. Managers created a racial division of labor and even segregated starting and quitting times. “There was a shadow of racism in it,” wrote Jennie C. Buckner of the St. Louis Urban League. “The dirty work was parceled out in the Negro community.” Such divisions belied the fact that despite their different experiences, all women working in the industry were precarious laborers working under exploitative conditions. All toiled in poorly ventilated rooms, and no health standards were in place. Unpredictable harvesting seasons created chronic turnover and exacerbated the employment cycle during market slumps. After the stock market crash, for example, some factory floors were “practically idle.” The combined weight of such negative attributes meant that anyone working in the field labored in a socially stigmatized, submarginal sector of the local economy.4

The bleak situation was that black working-class women were caught in a labor market that confined them to the dirtiest, lowest-paying, least desirable, least healthful, and most dangerous jobs in the city. For black women laboring in St. Louis during the 1930s, industrial employment offered very little compensation. Black women in the local nut-shelling industry were among the poorest workwomen in the city; approximately one-third of them were on the city’s relief rolls and some received funds from the Provident Association, a private charity that bore considerable responsibility for administering relief during the Depression’s early years. Black women made up the majority of African Americans on relief rolls, and black female manufacturing workers constituted the largest group on relief of any category. A Women’s Bureau Department of Labor report added the Gateway City to a list of other major cities like Chicago, Houston, Philadelphia, and Cleveland, where more than 40 percent of black women workers were jobless. Even despite Funsten Nut Company’s growth in sales over the course of the early twentieth century and its expansion to multiple plants, nut shellers’ wages were so meager that they significantly lowered statewide median wages—a fact not lost on organizers and statisticians. If “all the large group of low paid women in the nut-shelling plants was excluded in the St. Louis figures,” claimed Ruth I. Voris of the Women’s Bureau of the U.S. Department of Labor, then Missouri’s median wage values for women workers would have been noticeably higher. During the 1920s nut pickers earned a median income of only $4.60 per week, which was half of what laundry workers made and some dollars short of tobacco and bag workers’ earnings. In some cases, even domestic workers earned more than nut pickers. Ordinarily, however, “because of the larger wages paid in the factories, that is, Nut, Bag, Rag, etc., Negro applicants in this lower bracket constantly refuse offers of Domestic work,” one Urban League study reported. Though black women workers in the nut-shelling industry composed only a small fraction of the total number of black women workers in St. Louis’s paid labor economy, they composed the majority of the meager 7 percent of black women workers in industrial employment.5

Gendered Cartographies: Nut Factory Blues

Before the strike of 1933, the figure of the black female nut picker had already amassed cultural capital as the leading subject in St. Louis blues musicians Charley Jordan and “Hi” Henry Brown’s 1932 Vocalion Records tune “Nut Factory Blues.” Among a rising tide of black musicians who found commercial success through piercing analysis of the pain and possibility of black working-class life in the urban United States, these two blues artists contributed to the project of remaking the terrain of American popular culture by exploring quotidian worlds. As Amiri Baraka observes, urban blues reflected “the Northern Negro and the Southern Negro,” a binary suggesting that the “‘space’ that the city provided was not only horizontal; it could make strata, and disparities grew within the group itself.” Indeed, “Nut Factory Blues” exposed class fissures within black communities but also traversed more complicated and less explored ground as it mined the terrain of black working-class communal life through the prism of gender. In their construction of the black woman factory worker, Jordan and Brown suggest that the interplay between urban space, race, gender, labor, sexual relations, domestic violence, and household production becomes discernible. Bluesmen of the classical era crafted narratives of black women as economic actors—workers, producers, breadwinners—in effect making black women’s working-class subjectivity speak for and to broad processes.6

In “Nut Factory Blues,” space and place are prominent themes. “Down,” the descriptive term that bluesmen often use, immediately identifies demarcations within urban space, drawing the listener’s attention to its hierarchical dimensions. The bluesmen use the word to identify some of the mechanisms by which the city’s underbelly is exposed and examined. In the first stanza, the listener is located in the city’s downtown district, on Morgan and Sixteenth Streets. The intersection sliced through the fourth-largest neighborhood of five designated “black” districts, an area home to approximately nine thousand African Americans. Brown and Jordan juxtapose black working women and industrial capitalists to highlight the economic discrepancies between the two and to call attention to the ways that urban life facilitated “meetings” or transactions between individuals who otherwise lived separate lives. Their juxtaposition represented the stark gulf separating black women workers and those with power over women’s economic lives. It also marked the economic and physical intimacies these two groups shared precisely because of the ways power relations demanded economic exchange under coercive and subordinating terms. Conspicuous disconnection and inconspicuous intimacy coexisted at the points where these groups intersected. The second stanza takes the listener to an enclosed space below ground; the basement of a cold, damp, and dimly lit industrial factory. In locating black women here, Brown and Jordan point to the fact that managerial systems operated according to rigid, racial lines. As Baraka suggests, the bluesmen unveil carvings in city space and urban landscapes that corresponded with zones of class hierarchy, urban inequality, and labor exploitation.7

Jordan and Brown complicate their progressively fine-toothed cartography in the final line of the second stanza, where they invite the listener to ponder a kind of a gender distortion of mainstream black economic aspiration. While the song positions black women industrial workers at the bottom of the paid labor market, it nonetheless emphasizes that, at the very least, black women have standing within it. Black men, by contrast, lack standing within the world of industrial production. “Nut Factory Blues” starkly juxtaposes the black female industrial worker and the black unemployed husband, thus distorting the widely accepted formula of the family wage ideal by its offering of a consuming man and a producing woman. In Jordan and Brown’s reversal, black men bear gender while women hold economic status. In assigning black men to familial status, the bluesmen made a rhetorical move similar to that of intellectuals—especially social scientists, social workers, and justice seekers—when they situated black economic misery at the local and national levels within the larger context of a global financial crisis. For such commentators, the racial tint of class oppression found legibility through what they identified as the economic emasculation of black men and, concomitantly, the relatively higher labor force participation rates of black women when compared to the rates of white working women in the formal economy. This is to say that black women’s presence in the paid labor force, particularly in the industrial employment sector, indicated and indicted the economic inequality plaguing black working-class communities. It seems to be the case that the bluesmen were less interested in promoting a male breadwinner and dependent wife ideal as a solution than they were in exposing gender tensions, but whether one aimed to promote or expose the “problem,” in both cases the trope of the black working woman acted as a synecdoche in that through her the economic pain and social misery of the black nonworking husband, and by problematic extension, the black family, found articulation. Far from existing solely within spaces deemed formal, respectable, and professional, such critical exploration also found a home in the social worlds that black popular culture made.8

The spatial distinctions depicted in the second stanza of “Nut Factory Blues” offer a foundation from which to explore gender conflicts in black working-class households and communities. The bluesmen suggest a causal relationship between socio-spatial locations in the local economy and gender tension. Read together, the third and fourth stanzas show that conflict erupted in the liminal space between work and leisure as women received their pay and prepared themselves for the time they would spend away from the factory floor. In these scenes, black women workers encounter an additional coercive and exploitative exchange, this time with their husbands at the point of remuneration and the moments that immediately followed. We are told that women’s failure to bring their pay home and turn their checks over to their husbands resulted in two possible outcomes: abandonment or physical abuse. In its frank discussion of domestic violence and the contextualizing of such within the scope of black men’s and women’s varied relationship to “the economic,” “Nut Factory Blues” joined a tradition of social commentary in black popular cultures that mimicked blueswomen’s 1920s productions ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Abbreviations

- Introduction: The Labor of Dignity: Black Working-Class Women’s Organizing in the Gateway City

- 1. “We Strike and Win”: Food Factory Workers and Labor Radicalism

- 2. “Their Side of the Case”: Domestic Workers and New Deal Labor Reform

- 3. “The Fight against Economic Slavery”: Clerks and Youth Activism in the Don’t Buy Where You Can’t Work Movement

- 4. “Riveting the Sinews of Democracy”: Defense Workers and Double V

- 5. “Beneath Our Dignity”: Garment Workers and the Politics of Interracial Unionism

- 6. “Jobs and Homes . . . Freedom”: Working-Class Struggles against Postwar Urban Inequality

- Conclusion: The Legacies of Black Working-Class Women’s Political Leadership

- Acknowledgments

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index