- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

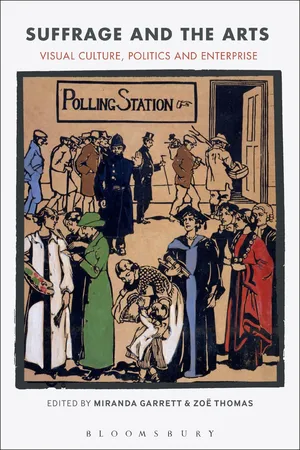

Suffrage and the Arts re-establishes the central role that artistic women and men-from jewellers, portrait painters, embroiderers, through to retailers of 'artistic' products-played in the suffrage campaign in the British Isles. As political individuals, they were foot soldiers who helped sustain the momentum of the movement and as designers, makers and sellers they spread the message of the campaign to new local, national and international audiences, mediating how suffrage activism was understood by society at large. Published to coincide with the centenary of the 1918 Representation of the People Act, which granted the vote to women over the age of thirty meeting a property qualification, this edited collection offers a range of new perspectives and readings of the outpouring of creative responses to the campaign.

Contributors, who include historians, art historians, curators, museum professionals and suffrage experts, call upon the historiographical developments of the last thirty years, alongside new archival discoveries, to showcase the vibrancy of ongoing research in this area. Throughout, chapters investigate the wider socio-cultural backdrop to suffrage and the women's movement, the difficult choices that were made between professional, artistic aspirations and political commitment, and how institutional and informal networks influenced creative expression and participation in feminist politics. From shining light on the use of portraiture to bolster the cultural cachet of the militant Women's Social and Political Union, uncovering the links between Victorian interior design, enterprise and suffrage, through to questioning the supposed conservativism of women's art institutions during the campaign and in the inter-war era, Suffrage and the Arts is a timely and important collection which will contribute to a number of scholarly fields.

Contributors, who include historians, art historians, curators, museum professionals and suffrage experts, call upon the historiographical developments of the last thirty years, alongside new archival discoveries, to showcase the vibrancy of ongoing research in this area. Throughout, chapters investigate the wider socio-cultural backdrop to suffrage and the women's movement, the difficult choices that were made between professional, artistic aspirations and political commitment, and how institutional and informal networks influenced creative expression and participation in feminist politics. From shining light on the use of portraiture to bolster the cultural cachet of the militant Women's Social and Political Union, uncovering the links between Victorian interior design, enterprise and suffrage, through to questioning the supposed conservativism of women's art institutions during the campaign and in the inter-war era, Suffrage and the Arts is a timely and important collection which will contribute to a number of scholarly fields.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Suffrage and the Arts by Miranda Garrett,Zoë Thomas in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Design & History of Modern Art. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART ONE

Institutional Politics

CHAPTER ONE

‘I loathe the thought of suffrage sex wars being brought into it’: Institutional conservatism in early twentieth-century women’s art organizations

Zoë Thomas

In 1950, painter Margaret Geddes (1914–1998) wrote an article about the history of the Women’s International Art Club – of which she was the Chair – for the celebrated art journal The Studio. Although the Club had been founded in Paris at the turn of the century, it quickly moved to London to ‘promote contacts between women artists of all nations and to arrange exhibitions of their work’. In her article, Geddes informed readers that:

There is a good deal of prejudice, both amongst the lay public and amongst artists themselves, against any society which exists exclusively for women artists, and the Women’s International Art Club has come in for its share of criticism … Whatever may have been the case in the past, it is said, nowadays there is surely no reason for women to segregate themselves in this way? It is apparently necessary, therefore, when writing of a women’s club, that one should start with an apology for its existence!

Geddes then proclaimed that she refused to ‘get involved in an argument about women’ and instead wanted to focus on the ‘interesting’ and ‘outstanding work’ at the Club’s exhibitions. A final caveat was added when she reassured readers that the group was ‘entirely non-political’.1 The article was published five years after the Second World War, twenty-two years after full emancipation had been granted to women in Britain in 1928. Written by a painter born in 1914, Margaret Geddes belonged to a later generation than many of the artists whose lives are explored within this collection. This extract is significant, however, as her comments reveal the prevalent anxieties about women’s art groups and intrigue about the political preferences of members in the 1950s, an anxiety that had been present throughout the suffrage campaign and had clearly continued long afterwards.

Geddes’ refusal to ‘get involved in an argument about women’ was the official stance taken by many of the major women’s art organizations in Britain across the early-to-mid twentieth century. Alongside the Women’s International Art Club, these organizations included groups such as the Society of Women Artists (founded during 1856–1857), the Glasgow Society of Women Artists (founded in 1882) and the Women’s Guild of Arts (founded in 1907).2 These organizations were created because women were often barred entry to prestigious male-only art institutions (no woman had been a member of the Royal Academy of Arts since the eighteenth century, for instance), which, alongside more insidious gendered prejudices, produced a masculine environment which dominated the professional art scene.3 Naturally, each women’s art organization developed different characteristics and aims. The Society of Women Artists was proud of its royal patronage and exhibited the works of those designated ‘amateurs’ alongside ‘professionals’ while the Women’s International Art Club concentrated on forging transnational links between artistic women at annual exhibitions, although, as Grace Brockington has shown, it was dominated by British members.4 In contrast, the Women’s Guild of Arts focused on providing an exclusive network for professional women associated with the Arts and Crafts movement. The Guild was formed because women were not allowed to join the Art Workers’ Guild, a prestigious group for radical male architects and designers, which was established in 1884 and prohibited female members from joining until 1964.

During the suffrage campaign and in the years that followed, individual members, separate from their activities within these art organizations, were often at the forefront of those advocating political and social reforms. They designed and made suffrage banners, posters, postcards and other ephemera, and their role in the fight for political and social change deserves greater prominence in histories of the movement, as does the potential of the arts to awaken a sense of selfhood that fed directly into feminist causes. But despite being institutions seeking to improve women’s professional and artistic opportunities, as the scholarship of Pamela Gerrish Nunn, amongst others, has demonstrated, the committees of all these major women’s art organizations appear united in their refusal to take a public stance on topics deemed overtly political, and there is little evidence of any sustained collective support for suffrage in the twentieth century.5 Alongside this, to date, it has been difficult for researchers to assess the institutional perspectives of the networks of women who made up these organizations due to a lack of surviving archival materials.6 However, a recently discovered archive pertaining to the, at times fraught, private institutional debates between different members of the Women’s Guild of Arts at the height of suffrage militancy, c. 1907–1913 – alongside reappraisal of the Women’s International Art Club’s meeting minutes – allows this chapter to focus on this apparent contradiction between the institutional and personal responses of female artists to suffrage and feminism.

Behind the scenes in early twentieth-century Britain, members of artistic women’s organizations had become increasingly polarized in their perspectives about feminist politics and the appropriate influence of this on the arts. The neutrality and abstention from political concerns which these institutions outwardly demonstrated were not mirrored in internal discussions. Debates raged, members resigned and opinionated letters were exchanged. Some began to find it impossible to separate the quest for equal citizenship from their positions as professional artists and became frustrated by institutional apathy. But for others, the daily gendered challenges they faced in the arts led them to prioritize the fight for artistic equality above fighting for constitutional reforms. Many identified first, and foremost, as artists (rather than disenfranchised women) and prioritized closing the gendered gap separating them from their male peers over their engagement in the electoral process. Crucially, it was felt by a considerable number that the heightened societal anxieties about gender relations and suffrage in the early twentieth century, and the increasingly separatist approach of suffrage groups such as the Women’s Social and Political Union, exacerbated gender tensions and moved women further from the ultimate goal of artistic gender unity. As such, these individuals greatly encouraged the organizations they were members of to avoid any discussions about gender or politics and to simply try and exist as exemplars of artistic expertise. As Helen McCarthy has noted, many women – working across the professions – were often ambivalent to feminist ideology because they instead wanted ‘to claim for themselves an identity that was not solely defined by gendered political struggle’.7

There was no obvious correlation, such as age, political allegiance or artistic field, between the women who were increasingly split between these two perspectives. The pursuit of ‘equality’, and what this objective represented to different women across the nineteenth and twentieth centuries in Britain, was influenced by fluctuating professional needs, class, ethnicity, age and a complex personal reconciliation of ideals and everyday necessity. Relative priorities could focus on the constitutional, civic, financial or (pertinent to the subject of this chapter) professional. Assumptions that the focal point of early twentieth-century feminist and women-centred politics was always ‘the vote’ are not tenable. As Lucy Delap has argued, it is ‘anachronistic to treat suffrage as coterminous with feminism’.8 Moving away from positioning commitment to suffrage as the sole marker through which women’s activity of this era is evaluated, this chapter shows that even the more conservative members of women’s art organizations were, in their own – not unproblematic – way, committed to promoting opportunities for professional equality. Addressing the multiplicity of, at times incompatible, ways women in the arts sought societal change, is vital when assessing why groups such as the Women’s Guild of Arts appear to have outwardly shown so little interest in suffrage. In so doing, this chapter stresses the need to situate the campaign amidst the wider historical landscape, as this provides a window onto the intersecting political and professional allegiances that shaped women’s priorities and responses to suffrage and feminism in twentieth-century Britain.

* * *

The Women’s Guild of Arts was established as an Arts and Crafts organization for women in 1907. Textile designer May Morris (1862–1938) was the driving force but others were involved in its foundation and early years, such as embroiderer Mary Thackeray Turner (1854–1907), tempera painter and art patron Christiana Herringham (1852–1929), gilder Mary Batten (1874–1932), embroiderer Grace Christie (1872–1953), muralist Mary Sargant Florence (1857–1954), sculptor Feodora Gleichen (1861–1922), calligrapher Florence Kate Kingsford (1871–1949) and stained-glass artist Mary Lowndes (1856–1929).9 There were approximately sixty full members and candidates gained membership through a vigorous entry procedure where their work was inspected and voted on by existing members. Members included many of the most renowned artistic women of the era, such as painter Evelyn De Morgan (1855–1919) and women who individually appear in many chapters of this book: Honorary Associate and embroiderer Una Taylor (1857–1922), illustrator Pamela Colman Smith (1878–1951) and interior decorator Agnes Garrett (1845–1935). London-based members encouraged women to join from across the country by offering reduced fees to ‘country’ members, which included individuals such as the weaver Annie Garnett (1864–1942) in the Lake District.10 Although the Guild was formed because women were not allowed to join the Art Workers’ Guild, official papers always avoided inflammatory statements about why it had been necessary to form a separate group for women. Across the first sixty years of the twentieth century, the Guild provided a, now largely forgotten, network for professional women active in the fine and applied arts, and facilitated regular lectures and meetings, informal demonstration evenings, exhibitions, parties and ‘At Homes’ in the homes and studios of members.

Members were much influenced by circulating debates about whether to collaborate professionally with, or separately from, men – a topic also being debated within suffrage societies.11 By the early twentieth century, female art groups were increasingly seen as concessionary among women who wanted to be defined as professionals as it was felt these groups created an unnecessary segregation of the sexes, strengthening perceptions of the feminine persona of the perceived amateur ‘lady artist’. In a 1913 letter from Guild member Feodora Gleichen to May Morris, Gleichen exemplified the view of many of her peers when she insisted there ‘ought to be no such thing as distinction of sexes in art’. She continued: ‘I have always been dead against any women’s societies of art … and if this society is going to become one of the many women’s society things, I shall certainly leave it. I only joined because I understood it to be on a totally different basis to these other narrow societies.’12 Instead, women sought to train, exhibit and work alongside men, while also joining a growing number of mixed-sex art groups. But despite the mounting feeling that women’s organizations were anachronistic, women continued to be deni...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle Page

- Title Page

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- Foreword

- Introduction

- Part One: Institutional Politics

- Part Two: Enterprise and Marketing

- Part Three: Paintings on Display

- Part Four: Representing Suffrage

- Index

- Imprint