- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

A Cultural History of Dress and Fashion in Antiquity

About this book

Whilst seemingly simple garments such as the tunic remained staples of the classical wardrobe, sources from the period reveal a rich variety of changing styles and attitudes to clothing across the ancient world. Covering the period 500 BCE to 800 CE and drawing on sources ranging from extant garments and architectural iconography to official edicts and literature, this volume reveals Antiquity's preoccupation with dress, which was matched by an appreciation of the processes of production rarely seen in later periods.

From a courtesan's sheer faux-silk garb to the sumptuous purple dyes of an emperor's finery, clothing was as much a marker of status and personal expression as it was a site of social control and anxiety. Contemporary commentators expressed alarm in equal measure at the over-dressed, the excessively ascetic or at 'barbarian' silhouettes.

Richly illustrated with 100 images, A Cultural History of Dress and Fashion in Antiquity presents an overview of the period with essays on textiles, production and distribution, the body, belief, gender and sexuality, status, ethnicity, visual representations, and literary representations.

From a courtesan's sheer faux-silk garb to the sumptuous purple dyes of an emperor's finery, clothing was as much a marker of status and personal expression as it was a site of social control and anxiety. Contemporary commentators expressed alarm in equal measure at the over-dressed, the excessively ascetic or at 'barbarian' silhouettes.

Richly illustrated with 100 images, A Cultural History of Dress and Fashion in Antiquity presents an overview of the period with essays on textiles, production and distribution, the body, belief, gender and sexuality, status, ethnicity, visual representations, and literary representations.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access A Cultural History of Dress and Fashion in Antiquity by Mary Harlow in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Fashion Design. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

Textiles

EVA ANDERSSON STRAND AND ULLA MANNERING

INTRODUCTION

In its widest definition, the term textile includes more than a woven fabric, it can denote any fibrous construction, including nets, braided, and felted structures. A textile is the result of complex interactions between resources, technology, and society. The production process of a textile, from fiber to finished product, consists of several different stages. It is important to note that even when different types of textiles were produced in different periods and regions, the textile chaîne opératoire involved the same stages of production, e.g. fiber procurement, fiber preparation, spinning, weaving, and finishing, and each stage involved several sub-processes. Thus, the production of a textile is the result of, on the one hand, resources, technology, and society and, on the other, the need, wishes and choices of a population, which in turn influence the exploitation of resources. Moreover, the availability of resources condition the choices of individuals and society.1

Textiles and Preservation

In Antiquity, textiles were made from natural fibers of either plant or animal origin. Like any perishable organic material, these fibers were subject to rapid decomposition in archaeological contexts and their preservation required special conditions to avoid their destruction by micro-organisms. Environmental conditions that affect the survival of plant and animal fiber materials in positive ways are acidic conditions, favoring the preservation of proteinaceous fibers; a basic environment does the same for fibers of vegetal origin. As most degradation requires the presence of air, many archaeological textiles are found in contexts where anaerobic and/or waterlogged conditions occur. Other conditions—like extreme dryness or permanent frost, or the presence of salt, or exposure to a fire that leads to the creation of carbonized samples, or through mineralization when coming into contact with metal salts—have also preserved many textiles. In Europe, most textile remains have been found in connection with burials, such as costumes, wrappings of human remains and/or grave goods, furnishing, and other utility textiles. As the organic materials in inhumation graves are exposed to heavy and fast degradation, textiles recovered from these contexts are often highly fragmented. In northern Europe, bogs and wetland deposits have preserved many complete wool textiles and other objects made of skin and fur.2 Other important contexts where textiles or associated goods may occur are ritual offerings, settlements, refuse heaps, earth fillings and, of course, in written sources and iconography. Depending on the context, geography, and chronology, textiles have survived in differing quantities and qualities from north to south, east to west.3 In southern Europe, preservation conditions are different, finds of textiles are less well-preserved and fewer finds are known.4 By contrast, the dry conditions of Egypt have allowed a vast quantity of textiles to survive, both in the form of whole garments but, more often, in fragments.

While textile designs vary greatly, textile technology and textile tools changed less in the period under examination. In general, people were using the same raw materials, fiber processing methods, tools and textile techniques all over Europe for most of the millennium between 500 BC–AD 500, but with varying intensity and purpose.

FIBERS FOR PRODUCING TEXTILES

Plant Fibers and Their Processing

Flax deriving from the annual plant of the Linacea species, notably Linum usitatissimum, hemp (Cannabis sativa), and nettle (Urtica dioica) are plants that were used to produce textile fibers in ancient societies across Europe, North Africa and the Near East.5

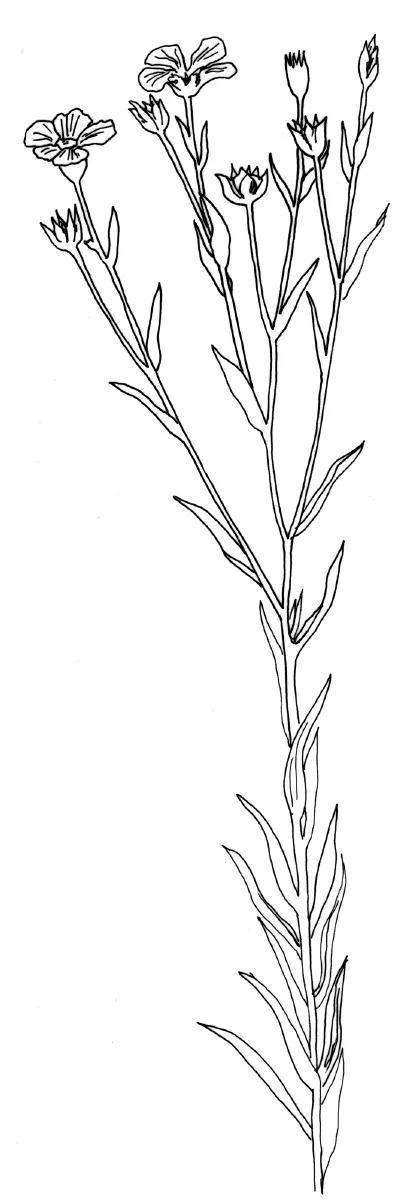

Flax (Figure 1.1) as a cultivated plant has always been considered to be one of the most important fiber plants used in ancient textile production.6 By comparing the size of preserved flax seeds from Germany and Switzerland, scholars have proposed that by the late Neolithic period (from c. 3400 BC), several different flax varieties already existed. This is supported by DNA analysis.7 Today the best quality flax fibers have a diameter of approximately 20 microns (0.002 centimeters) and are strong and soft with a fiber length of 45–100 centimeters. It has been suggested that prehistoric flax was shorter with a fiber length of 21–30 centimeters.8 Flax fibers have a silky luster and vary in color from a creamy white to a light tan. Linen textiles are cool to wear, since flax fibers conduct heat extremely well. Moreover, linen textiles have the propensity to absorb moisture very easily. At the same time, moisture evaporates quickly from them. During use, linen textiles can become almost as soft and lustrous as silk, but, in general, flax fibers lack elasticity.9

FIGURE 1.1: Flax. Courtesy of Margarita Gleba.

The best conditions for flax cultivation are fertile, well-drained loams. Depending on the region and climate, flax is sown at different times during the year. Since the roots grow near the surface and are weak, the soil has to be prepared carefully. Flax reduces the nutrients in the soil and a crop rotation with long gaps between sowing is required. The yield will otherwise be reduced and the flax will become more susceptible to disease, such as fungi attacks. During cultivation, flax needs regular access to water. It is likely that in ancient societies cultivation was well planned, especially where flax was produced on a large scale.10

When the flax is ripe it is pulled up by the roots and the seeds are stripped. The flax then has to be retted. The stems are either placed in water or spread on the ground. The moisture assists in the process of dissolving the pectin between the fibers, the bark and the stem. When flax is retted in water, it becomes extremely smelly, due to the bacterial activity. Retting pits were, therefore, usually placed outside settlement areas. The next step is breaking. In this process, a wooden club or another specialized tool, known as a break, is used to break up the dried stems and their bark in order to separate the fibers from the wooden parts (Figure 1.2). Then the flax has to be scutched, a process that scrapes away the last remains of stem and bark, which can be done with a broad wooden blade (Figure 1.3). Finally, the fibers are hackled or combed in order to separate them further and make them parallel; the fibers can also be brushed (Figure 1.4).11

FIGURE 1.2: Wooden club used to break the flax stems. © Annika Jeppsson and CTR.

FIGURE 1.3: Wooden blade used to scutch flax. © Annika Jeppsson and CTR.

FIGURE 1.4: Brush used for brushing linen fibers. © Annika Jeppsson and CTR.

Both hemp and nettle (Figure 1.5) fibers are prepared in a similar way to flax. Hemp was not used in Europe until the Iron Age.12 The hemp plant is taller than flax but the fibers are generally coarser. Most likely, hemp was preferred for the production of sails, ropes, and nets.

Archaeological finds of textiles made of nettle fibers are extremely rare, but some finds indicate that nettle was used as a textile fiber in northern Europe as well as in the Mediterranean region. Nettle fibers are, in general, shorter and thinner than flax and hemp fibers, but are well suited for producing textiles for clothing, as well as rope and other textile products. Since it is difficult to distinguish between hemp, flax, and nettle fibers, and this analysis requires specialist knowledge and equipment, archaeological plant fiber textiles have often been recorded as flax, although hemp and nettle fibers cannot be excluded. A renewed focus on species identification will hopefully provide new results on the use of various plant fibers in a European context in the future.13

Cotton is mentioned in Roman written sources, but evidence for its cultivation and use in Antiquity is scarce. It has ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Introduction

- 1. Textiles

- 2. Production and Distribution

- 3. The Body

- 4. Belief

- 5. Gender and Sexuality

- 6. Status

- 7. Ethnicity

- 8. Visual Representations

- 9. Literary Representations

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Notes on Contributors

- Index

- eCopyright