- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

A Cultural History of Dress and Fashion in the Medieval Age

About this book

During the medieval period, people invested heavily in looking good. The finest fashions demanded careful chemistry and compounds imported from great distances and at considerable risk to merchants; the Church became a major consumer of both the richest and humblest varieties of cloth, shoes, and adornment; and vernacular poets began to embroider their stories with hundreds of verses describing a plethora of dress styles, fabrics, and shopping experiences.

Drawing on a wealth of pictorial, textual and object sources, the volume examines how dress cultures developed – often to a degree of dazzling sophistication – between the years 800 to 1450.

Beautifully illustrated with 100 images, A Cultural History of Dress and Fashion in the Medieval Age presents an overview of the period with essays on textiles, production and distribution, the body, belief, gender and sexuality, status, ethnicity, visual representations, and literary representations.

Drawing on a wealth of pictorial, textual and object sources, the volume examines how dress cultures developed – often to a degree of dazzling sophistication – between the years 800 to 1450.

Beautifully illustrated with 100 images, A Cultural History of Dress and Fashion in the Medieval Age presents an overview of the period with essays on textiles, production and distribution, the body, belief, gender and sexuality, status, ethnicity, visual representations, and literary representations.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access A Cultural History of Dress and Fashion in the Medieval Age by Sarah-Grace Heller in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Fashion Design. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

Textiles

ELIZABETH COATSWORTH AND GALE R. OWEN-CROCKER

INTRODUCTION

The extremes of wealth and poverty of the Middle Ages, and the many levels between, were exemplified by the textiles that clothed bodies and furnished environments. Textiles were an essential and ubiquitous part of medieval life, from the luxurious and decorative to the utilitarian, from coronation robes and episcopal vestments to sanitary towels. The increasingly elaborate beds that became fashionable in the later Middle Ages required good quality mattresses, sheets, pillowcases, blankets, and bedcovers, as well as decorative, draught-excluding hangings around and above them. Table cloths and towels were used both in secular homes and at the altars in churches, and both environments also required seat covers, cushions, and the curtains which both insulated and provided a little privacy in the essentially public medieval existence. All of these soft furnishings were precious possessions, bequeathed in wills and inventoried among the possessions of their late owners or the churches to which they belonged. When traveling, medieval people made use of tents; cloth covered their waggons and wrapped their bundles of goods, which were tied with string or rope. Flags and sails of ships were made of cloth.

Most of the garments people wore were made of textile, supplemented with leather, fur, and metalwork. Dress was an identifying characteristic of gender, status, and role in life: the fiber that it was made of, the quantity of cloth, the expense of the dye, the elaboration of the finishing, all contributed to an impression of the wearer’s rank and calling. Ecclesiastical dress ranged from the undyed, coarse robes of monk and nun to the mass vestments of priests, bishops, archbishops, and popes, which at their most elaborate might be of expensive silk cloth, encrusted with pearls and gemstones, and decorated with embroidery in gold or silver. The rich and royal could command new outfits for every season and special occasions, of the finest native or imported cloth and the most fashionable colors of fur; even their horses were dressed in trappers sometimes decorated with the heraldry of their aristocratic owners. Many of the poorer people, in contrast, probably never owned a garment of new material: their clothes might be made up of pieces of old textile or items passed on from previous owners. In the early Middle Ages, and probably to the end of the medieval period in rural areas, domestically-produced textiles were normal. With the growth of towns, professionally-made garments and furnishings could be readily bought, both new and second-hand.

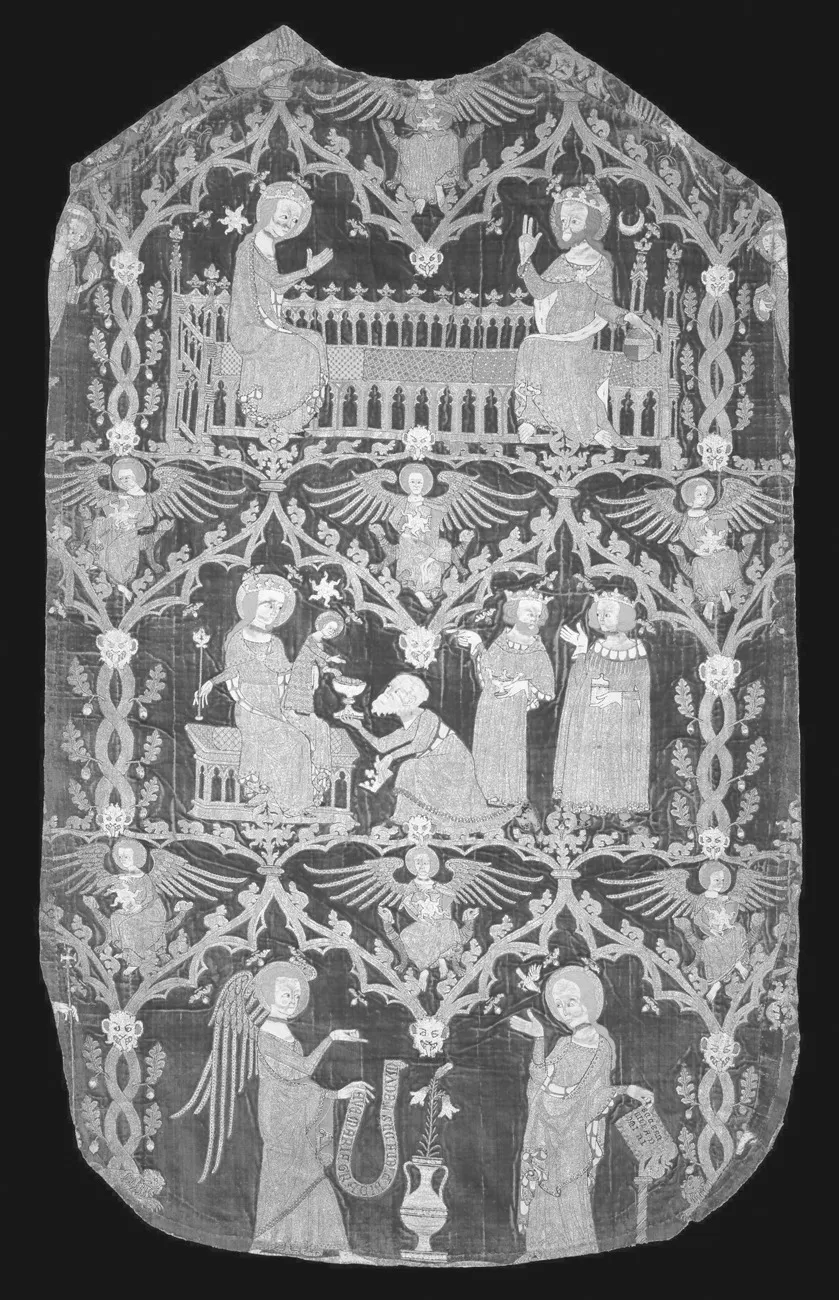

Textile was not only utilitarian: it could also be both decorative and instructive. Painted, embroidered, or tapestry-woven cloths might depict scenes from the life of Christ or the Virgin Mary, images of saints or inspirational secular stories, or they could carry emblems, such as the cross, the shell of St. James, the heraldic emblem of a family, or a composite of the arms of two families linked by marriage. Such decorative cloths could be found as wall hangings in churches and secular dwellings. Ecclesiastical copes, chasubles, stoles, and maniples were sometimes decorated with an embroidered, instructive, iconography (Figure 1.1). Heraldic imagery might represent the patron on precious textiles presented to the Church or it might make appropriate decoration on secular domestic furnishings.

The medieval textile industry was necessarily productive, keeping up with demand that was not only for purpose of replacement but was also subject to fashion, to competitive dressing and furnishing among the upper classes, and to the requirements of officials who needed to demonstrate their status through their clothes and household furnishings. Armies of merchants and cloth workers were also employed to produce textiles for individual occasions that might take months to prepare: providing wardrobes of clothes and furnishings for royal brides; costumes, hangings, and carpets for coronations. At more short notice, they provided for the funerals of major figures that might demand a pall cover and clothing given as charity to the poor who were hired as formal mourners, as well as clothing for the bereaved family.

FIGURE 1.1: Chasuble showing the famed English embroidery style called opus anglicanum, embroidery and pearls on velvet, c. 1330–50, British. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

In response to such demands, in the course of the Middle Ages textile production became increasingly commercialized, mechanized, regulated, and international.

RAW MATERIALS AND PRODUCTION

The manufacture of textile, from its start as plant or animal fiber, was one of the major sources of wealth in the medieval period, and at many stages was highly labor intensive, such that few people, whether as landowners, merchants, laborers, or craftsmen and women, would not have been involved in it at some level. The processes involving wool and linen would have taken place across the medieval world, for at least local use, though quality of raw materials or production, especially in weaving or dyeing, dictated which areas benefitted from international trade. Cotton, though grown in the Mediterranean area, was probably not exploited in northern Europe in the early medieval period, and was first used there as cotton wool for stuffing, especially for the padded doublets which became fashionable male dress. It came to be used increasingly as thread for weaving later in the medieval period. The production of silk, both thread and textile, took place for much of the medieval period entirely outside Europe: it was an expensive import for the luxury end of the market.1

The main raw materials of textile throughout the medieval period were the wool of domesticated animals (sheep and goats) and linen processed from flax crops and also from hemp, though there is less surviving evidence of the latter (Figure 1.2).

Sheep, smaller and more hairy, less wooly animals than the highly developed breeds of our own time, were an essential part of the medieval economy, providing meat, milk, and cheese for food, horn for various uses from knife handles to translucent panels for lamps and windows, and skin for parchment. Their coats yielded whole fleeces for warmth, as well as the sheared or plucked wool which was spun into thread. Primitive sheep moulted naturally, and it is likely that much of the wool for spinning was acquired by simply plucking and pulling it off a sheep (“rooing”). Such a natural method of harvesting wool would make it less liable to be prickly when woven into cloth than wool which had been sheared, producing sharp ends. Wool contains lanolin, a natural wax that protects sheep from the weather. Modern treatment of wool involves washing processes which remove the lanolin, but in medieval times the waterproofing qualities of wool would have been a large part of its appeal. Worsted wools were not scoured to remove this lanolin. Woolens were scoured but were then artificially greased.2 Since washing the woven cloth would have diminished this protective element, or the expensively generated surface texture of woolens, wool textiles were generally not immersed in water but were spot-cleaned (as was silk). Different substances were used to clean the cloth according to the nature of the stain. Fifteenth- and sixteenth-century German recipes include cleaning agents for stains from axel-grease, urine, wine, and ink.3

FIGURE 1.2: Sheep and goats depicted in the Old English Hexateuch, compiled at St. Augustine’s Abbey in Canterbury, second half of the eleventh century. Cotton Claudius B iv, fol. 22 v. © British Library.

Primitive sheep displayed a wide range of natural colors, from white and gray through shades of tan, brown, and blacks. Poor people, or those wishing to display simplicity in their dress for religious reasons, are likely to have used undyed material for their clothes and furnishings, but that does not mean that the textiles used by such people were necessarily monochrome: selection of wool by color at the spinning stage would mean that different hues were available to create striped or checked cloth; or a mixture of tones could have been used in weaving to produce mottled effects. Wool then, from the earliest medieval times was a fiber that would have been readily available to villagers at any time of the year, a versatile, practical material. Long stapled wool was competently spun into hard, glossy threads which are found preserved in the metal oxides of metalwork, chiefly women’s dress accessories, in furnished graves of the early Middle Ages (fifth to seventh centuries). Later, the introduction of the spinning wheel and of elaborate finishing techniques (see below pp. 21–22) made it possible to exploit shorter, woolier fibers, and a greater range of wool textiles was developed. While sheep breeds in the modern sense are not recognized before the eighteenth century, selective breeding, crossing-breeding of sheep from different areas, sometimes as a result of human population moves, ensured a considerable variety of types with different colors and wool qualities long before the end of the fifteenth century. Wool fabrics of different weights and textures were commercially produced, and the range of cloth types, together with the added value of different dyeing processes meant that in the late Middle Ages there was wide choice of wool cloths for different purposes and at different prices. Wool was used for garments, furnishings, and the sails of ships. Britain, especially England, was in the forefront of the wool trade, reaching its peak in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, exporting vast quantities, especially to Flanders for weaving and also selling to Italian merchants.4 Trade in soft Spanish merino wool developed from the twelfth century and this was exported in large quantities to England and Flanders for weaving.

Goats, which are biologically similar to sheep, have received less attention in relation to the medieval economy than sheep, and there is less archeological evidence of goat fiber in textile. However, they are known to have been domesticated early and they provided all the foodstuffs and materials that sheep did. Their fine hair may have been a luxury equivalent to wool: the correspondence of Boniface, the eighth-century Anglo-Saxon missionary to Frisia and Saxony, records that he sent goat-hair bedclothes and a cloak of silk and goat-hair to England as gifts;5 and fragments of well-preserved, gray, twill textiles preserved on prestigious square-headed brooches worn by women at Tittleshall, Norfolk, and Wasperton, Warwickshire, demonstrate that the soft underwool of goats was used to make a fabric similar to the “cashmere” of today. The Tittleshall garment, dated to the mid-sixth century by its accompanying brooch, was especially luxurious as it also had a fur collar or cape6 (Figure 1.3).

FIGURE 1.3: Tittleshall woman from grave 13 (Walton Rogers, 2013, figure 7.2) with “cashmere”-like cloak. She also wears a linen veil and linen under-gown. Illustration by Anthony Barton. © The Anglo-Saxon Laboratory. The authors are grateful to Penelope Walton Rogers for supplying this illustration.

Flax had been introduced into northwest Europe in prehistoric times and was cultivated for linen by methods that, in some regions, hardly changed until as recently as the early twentieth century.7 Flax cultivation was arduous and labor-intensive. It began with the preparation of the fields in early spring, planting after the last frost, and constant weeding until the harvesting of the crop three to four months later. The flax plant, Linum usitatissimum L., is fast growing and may reach a height of 100–145 centimeters (over 4 feet). At harvest time, the stems were pulled by hand and the seeds removed by combing or rippling, after which the stems were retted to loosen the fibers from the outer bark. Retting involved leaving the stems in water for about three weeks. This could be achieved by spreading them in dewy fields or by using rivers; alternatively, some flax producers seem to have dug ponds, or exploited existing ones, which avoided the polluting effect of the rotting process on the local river. The stems were then hung up to dry, after which they were beaten with a mallet to loosen the woody part of the stems, then scutched with a heavy knife-like tool to release the inner fibers. These fibers were then heckled (or hackled), passed through a series of combs with metal spikes, to remove the last traces of the woody outer coating. The resulting cleaned fibers could then be wound round a distaff in preparation for spinning. Spinning was carried out in the same way as for wool, with a drop spindle (below), until the introduction of the spinning wheel, and it was woven on the same kinds of loom. It could be dyed, but was most often used undyed, in the creamy-white color it assumed after bleaching. Flax cloth could be washed frequently. Laundering was a predominantly female task, and in towns with public facilities, or at washing places on rivers, it was a social, communal activity. Linens were immersed in water and rubbed with soap, made from animal fat and lye, an alkaline liquid, then rubbed together and beaten.8 After drying, it could be bleached, and pressed smooth with a hot stone or a ball of glass. Although linen could be used for outer garments, the fact that it could be laundered made it especially suitable for undergarments, so that people could wear fresh, clean clothing next to their skin. Richer people, who owned more shirts, and who could afford to pay for laundry, might appear fresher and cleaner than the poor who could not spare their few clothes to be laundered very often. Its washable nature also made linen suitable for textiles subject to staining, such as table linen, towels, and bedding. Churches were required by statute to keep their altar linen clean, though lazy priests and impoverished parishes might not always maintain standards.9

Cotton is also a plant fiber. It is harvested from the fluffy boll, or capsule, found protecting the seeds of shrubs of the genus Gossypium. Pr...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Introduction

- 1 Textiles

- 2 Production and Distribution

- 3 The Body

- 4 Belief

- 5 Gender and Sexuality

- 6 Status

- 7 Ethnicity

- 8 Visual Representations

- 9 Literary Representations

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Notes on Contributors

- Index

- eCopyright