- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Natural History of Moths

About this book

The Natural History of Moths covers all aspects of moth biology and ecology.

Moths are often as beautiful as butterflies, and with more than 2,000 species on the British list they are more numerous, more diverse and occupy a far wider variety of habitats and lifestyles. Yet for most naturalists they remain a little-known and neglected group. Not since E. B. Ford's 1955 New Naturalist volume has the biology of moths been treated in a popular book. Here, Mark Young sets out to redress this imbalance and to show the great variety and interest of these sometimes striking, sometimes subtle insects. He draws together the results of amateur study and the latest scientific research to paint a broad picture of all aspects of moth biology, brought to life with many fascinating examples from the moth faunas of Britain and abroad.

The breeding, feeding, distribution and life-history ecology of moths are described, in addition to more specialised aspects of their biology, such as pheromone atraction of mates, interactions with host plants, and the anti-predator responses that many moths use to foil bats and birds.

While butterfly conservation problems have often provided headline news in the press, the difficulties facing moths have received much less attention. However, threats arising from the loss and degradation of natural habitats have had no less effect on moths, and have endangered many more species. The status and fortunes of many moths are still unknown, but a growing number of success stories. such as that of the Black-veined Moth, point the way to better practice for the future, and to the preservation of this enormous wealth of beauty, diversity and natural history interest.

Moths are often as beautiful as butterflies, and with more than 2,000 species on the British list they are more numerous, more diverse and occupy a far wider variety of habitats and lifestyles. Yet for most naturalists they remain a little-known and neglected group. Not since E. B. Ford's 1955 New Naturalist volume has the biology of moths been treated in a popular book. Here, Mark Young sets out to redress this imbalance and to show the great variety and interest of these sometimes striking, sometimes subtle insects. He draws together the results of amateur study and the latest scientific research to paint a broad picture of all aspects of moth biology, brought to life with many fascinating examples from the moth faunas of Britain and abroad.

The breeding, feeding, distribution and life-history ecology of moths are described, in addition to more specialised aspects of their biology, such as pheromone atraction of mates, interactions with host plants, and the anti-predator responses that many moths use to foil bats and birds.

While butterfly conservation problems have often provided headline news in the press, the difficulties facing moths have received much less attention. However, threats arising from the loss and degradation of natural habitats have had no less effect on moths, and have endangered many more species. The status and fortunes of many moths are still unknown, but a growing number of success stories. such as that of the Black-veined Moth, point the way to better practice for the future, and to the preservation of this enormous wealth of beauty, diversity and natural history interest.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Natural History of Moths by Mark Young,Lyn Wells in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Entomology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

An Introduction to Moths

An Introduction to Moths

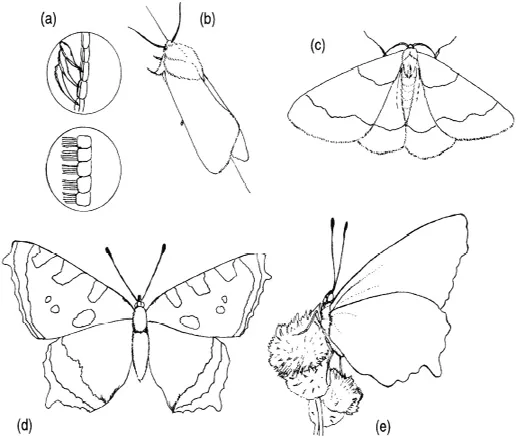

The contrast between a butterfly, a ‘typical’ moth and a burnet moth (not to scale).

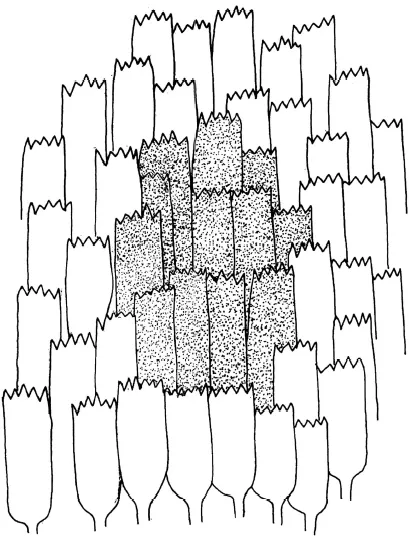

MOTHS are members of the great insect order, Lepidoptera, which includes the more familiar butterflies — both have scale-covered wings, from which the scientific name is derived (Gk lepis=scale, pteron=wing). These scales are set like roof slates all over the wings and are the fine dust which rubs off so easily on to inquisitive fingers. Each scale is coloured and it is the mosaic of these myriad colours that gives butterflies and moths their fascinating and subtle patterns and colour schemes.

Butterflies have always received more notice than moths, no doubt because of their day-flying habits and their generally more gaudy appearance, but I hope to convince you that moths deserve their share of attention too. They can be as brightly coloured — in fact many, like the ‘burnets’ (Zygaenidae) or the ‘tigers’ (part of the Arctiidae) are constantly mistaken for butterflies — and some of them are also day-flying, so that they can claim all the attractions of butterflies. In addition, moths have a wealth of extra features: such as the ability of some to detect bats' ultrasonic squeaks and either to take evasive flight or to produce their own confusing noises in return (see Chapter 8); or the well known trick of releasing powerful scent to attract potential mates from over a kilometre away (see Chapter 7). My purpose in this book is to review what is now known about these and many other exciting aspects of moths' natural history, illustrating this with information from recent scientific research.

FIG 1 Scales from the wing of a moth.

A BUTTERFLY IS JUST A MOTH BY ANOTHER NAME

There is no proper answer to the question what is the difference between a butterfly and a moth?'. We have chosen to give the label ‘butterflies’ to members of a small number of related families within the order Lepidoptera. In these families the species generally share certain habits and features. They are day-flying; have colourful wings; hold their wings closed over their backs when at rest; have clubbed ends to their antennae: and by these combined characters we have come to know them. However, the ‘skipper butterflies’ hold their wings in various angled positions and have only moderately thickened antennae, whereas the ‘burnet moths’ (for example) are colourful, day-flying species, with well thickened ends to their antennae and we might well ask why they are not also called butterflies.

FIG 2 Contrasting features of butterflies and moths. (a) Detailed structure of antennae; (b) a moth at rest, with ‘roof-like’ folded wings and simple antennae; (c) a geometrid moth at rest, with wings flat; (d) a butterfly, showing ‘knobbed’ antennae; (e) a butterfly at rest, with wings held above the body.

COUNTING SPECIES

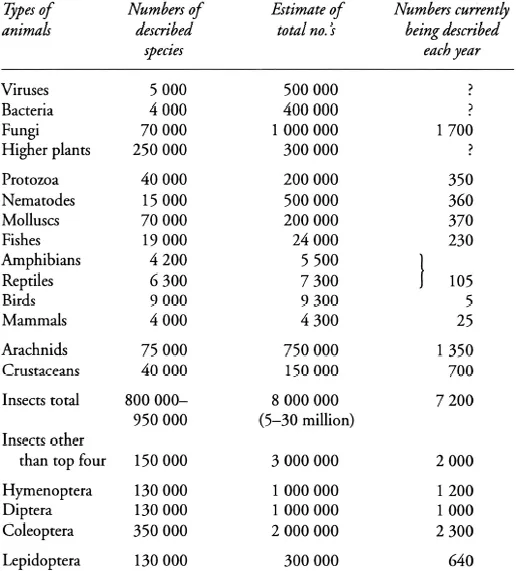

The Lepidoptera include about 130000 known species, with an incalculable number still to be found and described, especially in the tropics (Groombridge, 1992; Nauman, 1994). Of these, the butterflies account for around 18500 species, or only 12%; this alone indicates why there is so much to be gained from studying moths. Lepidoptera are one of the ‘big four’ insect orders, equalled or exceeded in number only by the true flies (Diptera), with 130000 species; the bees, wasps, ants and saw-flies (Hymenoptera), with 130000 species; and the beetles (Coleoptera), with 350000 species. Together these four orders make up 80% of the insects and a staggering 33% of all known animals. The paltry tallies of mammals, 4000 species, and birds, 9700 species, are put into stark perspective by the richness of insect species. On average, around 700 new species of Lepidoptera are described each year, whereas only 5 or so new birds and about 25 new mammals are found.

TABLE 1 The approximate numbers of different types of animals and plants.

Source: Simplified with permission from Groombridge (1992).

Even in temperate regions, where insects might be expected to give way to warm-blooded mammals and birds, there are still many species — the lepidopterous fauna of Britain numbers around 2400, including the strays and regular migrants described in Chapter 3 (Emmet, 1991a). Although the 65 or so butterflies found regularly in Britain cover a wide range of habitats and show many interesting features, the moths are incomparably more widespread and varied in their occurrence, influence and behaviour.

MOTHS ARE FOUND EVERYWHERE

There are no marine moths, but on the autumn strand line of sandy shores in southern and eastern Britain, the eaten leaves of Sea Rocket (Cakile maritima) indicate the presence of the larvae of the Sand Dart moth (Agrotis ripae) in the sand beneath the plant. The moth itself can then be caught at ‘sugar’ (see Chapter 9) on the beach the following summer. Just above the high tide mark of rocky shores, the larvae of the Dew moth (Setina irrorella) feed on lichens splashed by the waves. There are no moths that live permanently on snow fields either, but many can be found feeding on the sparse vegetation that is briefly free from snow on mountains in summer. Wherever there are plants, there are moths, but they also use a very much wider range of foodstuffs and turn up in the most unlikely places. One family, the Tineidae, specialises in feeding on fungus, or animal, or plant debris, and often shares human habitations. Dryadaula pactolia, now widespread but originally from New Zealand, has been found feeding on fungus in wine cellars; Monopis weaverella includes fox faeces in its diet; Tinea pellionella (amongst others) has moved from birds' nests to clothes; and Myrmecozela ochraceella eats debris in wood ants' nests.

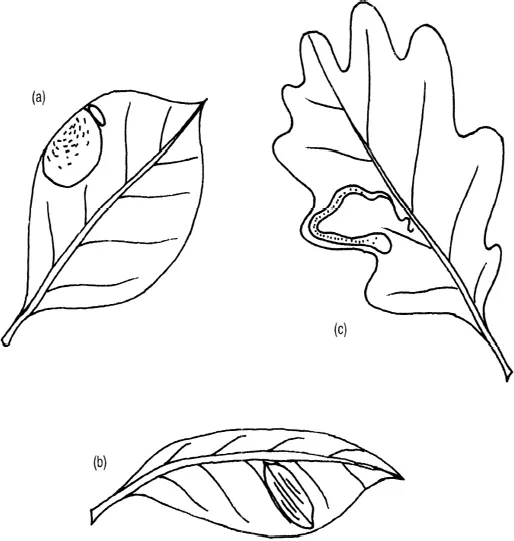

FIG 3 Leaf mine patterns. (a) Antispila sp. (Heliozelidae); (b) Phyllonorycter sp. (Gracillariidae); (c) Stigmella sp. (Nepticulidae).

The tiny size of the larvae of some moths also allows them to use highly restricted and specific food stuffs and there are many species whose entire larval life and growth takes place between the layers of one leaf (Hering, 1951). The family Nepticulidae shows this habit and, as the larvae feed, they slowly cut out a long mine in their leaf; since the mine is enclosed there is no exit for disposal of the faeces, which are piled behind the advancing larva, sometimes in intricate patterns. When the larvae are fully grown they bore out of the leaf and drop to the ground, forming a tough silken cocoon in which to pupate. Like most moths, leaf-mining species are usually restricted in their choice of foodplant and so the lepidopterist can find mined leaves and, knowing the foodplant, the shape and size of the mine, and the particular pattern of the faeces (usually called ‘frass’) can identify the species of moth that has done the damage. Other families of moths also make mines in leaves and this strategy, providing a sheltered environment and constant access to food, albeit on a very small scale, has clearly been a successful one (see Chapter 5).

Other moths, especially the Sesiidae, or ‘clearwing’ moths, feed inside the stems and trunks of trees and bushes, but as the nutritive value of wood is rather limited, the slowly growing larvae often spend two or more years feeding. Clearwings, as so aptly described by their common name, lack most of the scales on their wings and generally look more like wasps, bees or flies than moths. This is a defensive strategy similar to that of the wasp-mimicking hoverflies, and the resemblances can be striking and alarming (see Chapter 8).

MOTHS AS HERBIVORES

Most people are more familiar with the typical feeding habits of free-living larvae. Some of these larvae are so large that their depredations are clearly visible, in the form of extensive damage to leaves; this is obviously a potential problem to the larvae, which do not wish to advertise their presence to hungry bird predators. When lepidopterists search for larvae they often do so by looking for the feeding signs and there is clear experimental evidence that birds do the same (see Chapter 8). It is possible to find the finger-sized larvae of the Poplar Hawk moth (Laothoe populi) by noticing the dry, pea-sized black droppings on pavements beneath poplar trees, for even one larva eats a prodigious amount of leaf and produces a comparable amount of frass. Most larvae are much smaller but they may be so abundant that their presence is just as obvious as that of the Poplar Hawk moth. The Winter moth (Operophtera brumata) can be so common that it defoliates fully grown oak trees and the noise made by the frass pellets hitting the dry leaves on the forest floor can sound like heavy drizzle. This moth is an important pest and has been studied very extensively; therefore it appears in many places in the chapters that follow. In Britain, at least, this is one of the species that the gardener tries to foil by putting grease bands around the trunks of apple trees, for the females are wingless and have to crawl up the trunks on their way from their pupation sites in the soil to their egg-laying sites on the twigs of the trees (see Chapter 4).

There is another group of defoliating moths, whose larvae are prolific silk spinners, the ‘ermine’ moths of the family Yponomeutidae. In northern Britain, the Bird Cherry Ermine (Yponomeuta evonymella) often causes the complete defoliation of Bird Cherry (Prunus padus) trees for several years in a row (see Chapter 5).

Even the smallest urban garden provides a home for many species of moth, and in a suburban setting, with many nearby gardens and mature trees, the number of species runs into hundreds. They are accessible to everyone who is shown how to find them; that they are not always immediately visible is because they have to avoid predators.

THE CLASSIFICATION OF MOTHS

Moths are closely related to caddis flies (Trichoptera) but the latter are immediately separable by the presence of hairs on their wings (hence ‘trichos’ = ‘hair’ in their scientific name). Some moths have modified hair-like scales on parts of their wings but they always also have true scales; even so it is possible to mistake some small moths for caddis flies. In fact, there are over twenty characters that reliably differentiate moths and caddis flies, but the three most primitive suborders of moths have features that make them resemble the caddis.

So far, moth classification has depended on examination of morphological structures, occasionally including the egg, larval and pupal stages, but adult characters have been paramount. Different authors give different weight to a variety of morphological systems. The mouthparts have been used to help iden...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Dedication

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Colour Plates

- Preface

- Chapter 1 - An introduction to moths

- Chapter 2 - The origins and distribution of Britain's moths

- Chapter 3 - Dispersal and migration of moths

- Chapter 4 - Life cycles and hibernation

- Chapter 5 - Plants as food for moths

- Chapter 6 - Plant defence against larvae

- Chapter 7 - The mating behaviour of moths and the use of pheromones in the control of moth pests

- Chapter 8 - Moth predators and population dynamics

- Chapter 9 - Catching and studying moths

- Chapter 10 - Conservation of moths

- References

- Plates