eBook - ePub

Shakespeare's Theatres and the Effects of Performance

- 306 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Shakespeare's Theatres and the Effects of Performance

About this book

How did Elizabethan and Jacobean acting companies create their visual and aural effects? What materials were available to them and how did they influence staging and writing? What impact did the sensations of theatre have on early modern audiences? How did the construction of the playhouses contribute to technological innovations in the theatre? What effect might these innovations have had on the writing of plays? Shakespeare's Theatres and The Effects of Performance is a landmark collection of essays by leading international scholars addressing these and other questions to create a unique and comprehensive overview of the practicalities and realities of the theatre in the early modern period.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Shakespeare's Theatres and the Effects of Performance by Farah Karim Cooper, Tiffany Stern, Farah Karim Cooper,Tiffany Stern in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Shakespeare Drama. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

The Fabric of Early Modern Theatres

Chapter One

‘This Wide and Universal Theatre’: The Theatre as Prop in Shakespeare’s Metadrama

Tiffany Stern

It is sometimes said that the early modern playhouse was a hearing, rather than a seeing, space. ‘Audience’, or ‘auditors’, or ‘hearers’, words regularly used for the people who attended plays, are said to indicate that the theatre was a place where language flourished, perhaps in the face of the visual.1 Up to a point, this is true: when Moth, preparing to perform young Hercules in Shakespeare’s Love’s Labour’s Lost, suggests ‘if any of the audience hiss, you may cry, “Well done, Hercules”!’ (5.1.129–30), he is indicating a trick he will play on a group of people who are not only intently listening to the production but also responding to it with sound. If they hiss him, says Moth, he will pretend the sound they make issues from his property snake: he will embrace and reinterpret the audience’s noise within the aural world of his performance. Less complicatedly, when the Chorus to Henry VIII calls the audience ‘gentle hearers’ he unites the people before him as noble listeners; his stress on the aural is linked to a request that the ‘hearers’ ‘think ye see / The very persons of our noble story’ (Prologue, 17, 25–6), and allow imagination to prevail over aspects of the theatre’s pretence.

Yet concentration on the auditory has led to a neglect of other and contrary references. Shakespeare, like many writers of his time, also called his audience ‘spectators’. The Chorus to The Winter’s Tale specifically reverses the terminology used in Henry VIII, addressing the audience as ‘gentle spectators’, even though similarly begging them to heighten the experience with their imaginations: ‘imagine […] that I now may be / In fair Bohemia’ (4.1.20–1). As it seems, then, the audience might equally be conceived of as, primarily, devoted to ‘hearing’, or devoted to ‘seeing’ – but, either way, the expectation is that on occasion they will bolster their physical experiences with imagination.

Imagination was requested because hearing and, even more obviously, seeing, were dictated by the theatrical spaces in which they took place. The visual vitality of London’s theatres was such that they repeatedly, and confidently, conveyed one and the same thing, imposing it on to all plays: themselves. With their painted ceilings, pillars and stage background they offered an unchanging backdrop for every play mounted within them; with their universal lighting, they imposed the same mood on to every drama. The fixed features of these theatres could not be substantially remoulded for specific performances, and few efforts seem to have been taken to change general ambiance from one production to another. Though references suggest that genre-specific hangings might be employed – black hangings signalling a tragedy (so making a literary rather than a ‘realistic’ statement) – general staging seldom acknowledged the separation of one play from another. It is the fact that every play had, essentially, the same staging, that explains that repeated plea for imagination found throughout Shakespeare: imagination was required not to flesh out the empty stage, but to override or reshape the permanent features that playhouses imposed on every production. Yet often, as this chapter will show, what ‘imagination’ actually consisted of was more rooted in the theatre than Shakespeare may have realised.

One indication of how prominent the playhouse’s appearance was to the theatrical experience is the fact that the round, outdoor playhouse in which Shakespeare’s early plays had been performed was named ‘The Theatre’. As writers of the time knew, ‘theatre’ was ‘Greek […] derived from a verb that signifies to See […] Whence a noun that signifies a Theater, where persons are brought forth to be shown unto people.’2 Watching and being watched, observing and being observed, and showing and being shown were activities heralded by the space – and the other round theatres that imitated it. Plays always had to fit around, utilise or add to what the stage was, visually, offering; all of the major theatres, round and square, for which Shakespeare wrote, are described as being stunning not to perform in (or watch performances in) but to look at: ‘the gorgeous Playing place erected in the fieldes […] as they please to have it called, a Theatre’; ‘the Globe, the glory of the banke’; ‘the new Globe […] which is saide to be the fairest that ever was in England’; and the theatre for which ‘great charge and troble’ was spent, the mysterious ‘Torchy [Black]friars’.3

It is only to be expected that Shakespeare would call attention to the visually charged theatrical environments his plays continually negotiated. He did so in a series of pointed theatrical references to actors, theatres and staging; references that were examined collectively in book-length form by Anne Righter (later Anne Barton) in her influential Shakespeare and the Idea of the Play of 1962. Like others after her, Righter saw Shakespeare’s theatrical allusions as compensatory and, often, subversive: the theatre was, thought Righter, what was left behind when imagination failed. Shakespeare, Righter argued, learned to hate his stage; ‘shortly after the turn of the century […] the actor, all his splendour gone, became a symbol of disorder, of futility, and pride’: Hamlet’s references to actors as ‘robustious periwig-pated fellow[s]’ (3.2.9) were, Righter felt, Shakespeare’s attempts to do down an environment he now despised.4 Yet, when Hamlet is made to criticise players who ‘tear a passion to tatters’ and ‘split the ears of the groundlings’ (3.2.10–11), he may equally be expressing the quiet confidence of a playwright assured of the Chamberlain’s Men’s acting superiority. For Hamlet, performed in 1601 when Shakespeare’s company was at the height of its success, and had recently built its new Globe theatre, is filled with references to playing, to staging, and, as will be discussed, to the Globe itself. Given that Shakespeare had a hefty financial stake in the Chamberlain’s Men, it seems more likely that Hamlet is drawing attention to the company’s unassailable performing superiority and its unmatched stage than critiquing it: not least because, as a ‘sharer’, Shakespeare probably oversaw the building of – and perhaps even helped design – the Globe itself.

Shakespeare’s many self-conscious gestures towards his theatre are, these days, often described as ‘metatheatrical’ or ‘metadramatic’ – vocabulary derived from Lionel Abel’s 1963 Metatheatre: A New View of Dramatic Form.5 Both words are used particularly for the moments when Shakespeare’s theatre comments on itself in some way: by staging plays-within-plays, or by referring to the playhouse’s physical structure. But the nomenclature of ‘metatheatre’ and ‘metadrama’ comes with interpretative baggage. Sometimes Shakespeare’s recourse to metatheatre is said to show that his plays are about dramatic form: that Shakespeare in his plays repeatedly and worriedly reflects on what drama means, how reality can be moulded theatrically, and how to elevate the stage as an art.6 Alternatively Shakespeare’s metatheatre is said to prefigure Brecht’s ‘verfremdungseffekt’ or ‘alienation-effect’: thus Shakespeare’s plays are said to be ‘subversive’ in their ‘level of anti-realism’ because they need to palliate ‘the dangers … in the deceptions of realism’.7 Both approaches to Shakespeare’s metatheatre share with Righter a sense that theatrical reference is negative. The first imagines that Shakespeare was conflicted about his art – an idea voiced by Hazlitt and Lamb in the nineteenth century, but not necessarily true of a period before English literature was sub-divided into ‘high’ and ‘low’, with theatre falling into the ‘low’ category. The other imagines that Shakespeare, like Brecht, set out to alarm his audience with stage references. But while it is true that Brecht’s emphasis on the theatrical will have been shocking to spectators used to staged ‘realism’, Shakespeare, writing for a non-illusionistic stage, would hardly surprise spectators by telling them that they were in the theatre.8 Indeed, Shakespeare’s reference to a theatre that was so visually a part of performance could be seen as the reverse of alienation: it celebrated the space, while letting the spectators off the hook, allowing them the relaxing option of not, for once, having to add imaginative fancy to what they see in order to believe.

Against writers who, from Righter onwards, have found Shakespeare’s theatrical references alienating or artful, this chapter will argue that, on the contrary, such references are proud acknowledgements of staging possibilities. Examining Shakespeare’s approach to the visual and aural aspects of his playhouses, it will concentrate on the many moments when Shakespeare, for all his requests to overcome stage limitations through ‘imagination’, carefully worked with what was in front of him; it will suggest that early modern theatres were, as props, enthusiastically, if complicatedly, employed.

As few structural features beyond that of the stage itself have been written about, the argument will look at what surrounded the stage from below (the ‘hell’ with its ‘trap’), from above (the ‘heaven[s]’), on the stage level itself (‘earth’ and its ‘pillars’), and from behind (the ‘scene’ with its ‘balcony’ and ‘ladders’; and the ‘tiring-house’ with its stage ‘bell’). In doing so, it will investigate the various statements, metaphors and analogies the stage made for and about itself, and their interpretative ramifications for Shakespeare. So the first section will discuss the broad ‘theatrum mundi’ construction of Shakespeare’s theatres, with their ‘heaven’, ‘hell’ and ‘earth’. The second section will turn to the stage when it is frank about its architecture, considering the factual and fictional use of the pillars. The third section will explore ways in which the stage might exploit its literary geography, considering the literal and metaphorical function of the backstage ‘scene’. The fourth section will investigate the theatre at its most functional and realistic, examining use made of the (tiring) house and balcony. Finally the stage’s most fixed aural prop, the stage bell or clock, will be explored. Shakespeare’s complexity, and his profoundest ‘metatheatre’, this chapter will suggest, is angled to the ways in which the physical reality of the stage met the fictions enacted upon it. Exploring the meaning of stage space as location and prop, this chapter will suggest that Shakespeare used his theatre’s construction itself as a prime locus of imaginative power.

THE STAGE AS WORLD: HEAVEN, HELL, EARTH

It is often pointed out that Shakespeare’s regular references to the world as a stage – ‘all the world’s a stage’ (As You Like It, 3.1.139), ‘I hold the world […] but as […] a stage’ (The Merchant of Venice, 1.1.77), ‘let this world no longer be a stage’ (2 Henry 4, 1.1.155) – refer to the ancient classical motif of ‘theatrum mundi’ (literally, ‘the world as stage’). This has even been said to be ‘the master-metaphor’ of Shakespeare’s canon: a metaphor Shakespeare used to remind the spectators that they themselves were not much different from actors, with movements and will prescribed by God, or the Devil, or the King.9 That, though partly true, is to forget that the very theatrum mundi metaphor was complicated by stage terminology. For when the wood that had made up what was named ‘the Theatre’ was reused to make what was named ‘the Globe’, Shakespeare’s ‘stage’ literally became his ‘world’ in a way that blatantly appropriated the master-metaphor. As, in both cases, the stage remained a stage, however, the power of the metaphor was reduced. This was a problem that beset other playhouses of the time in one form or another, for parts of the stage had been given names so reflective of the theatrum mundi motif – in particular, ‘heaven’ and ‘hell’ – as to turn plays into conceits protected from reality by their obviously fictional universe.

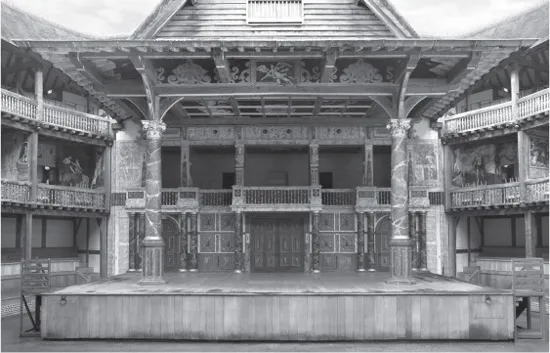

Figure 1 Tiring-House – front view, with ‘heaven’ above and ‘hell’ below. Architectural detail of Shakespeare’s Globe, photograph by Pete Le May. With kind permission of The Globe Theatre

‘Am I in earth, in heaven, or in hell?’ (Comedy of Errors, 2.2.211) asks Antipholus of Syracuse. Titus declares that ‘sith there’s no justice in earth nor hell, / We will solicit heaven’ (Titus Andronicus, 4.3.50–1); Hamlet exclaims upon the same three options ‘O all you host of heaven! O earth! What else? / And shall I couple hell?’ (Hamlet, 1.5.92–3). While these characters are referring to early modern ideas about the structure of the universe, with heaven above, earth in the middle, and hell below, they are also all, simultaneously, making references to the structure of the theatres in which they perform. For as Thomas Dekker makes clear when he describes how tailors ‘(as well as Plaiers) have a hell of their owne, (under their shopboard)’, the area under the stage was known as ‘hell’ in playhouses – a leftover from the religious staging adopted for Medieval Mystery plays.10 Likewise, as Heywood articulates when he writes of ‘the coverings of the stage, which wee call the heavens’, the roof that overhung the performers was, conversely, known as ‘heaven’ or ‘the heavens’.11 The stage where the actors performed, with heaven above and hell below was, as a consequence, the earth itself. Analogies comparing the theatre to the progress of man’s life, regularly equate the stage with earth for this reason, and there is a possibility that the stage space was sometimes entitled ‘earth’ to match its ‘heaven’ and ‘hell’ counterparts: ‘hee thinkes hee is placed in this world as in a royall Theatre: the Earth, the Stage, the Heavens the Scaffolds round about’; ‘The Earth’s the stage, heaven the spectatour is / To sitt and judge what ere is done amisse’.12

Each of the three Shakespearean characters named above, then, is speaking lines that seem metatheatrical, both verbally and visually, but that are also literal. The literal will have been highlighted by the fact that references to the spaces...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Contents

- Preface

- List of Illustrations

- List of Contributors

- Introduction

- Part One: The Fabric of Early Modern Theatres

- Part Two: Technologies of the Body

- Part Three: The Sensory Stage

- Acknowledgements

- Notes

- eCopyright