- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Puffin

About this book

A comprehensive monograph on the Atlantic Puffin. With its colourful beak and fast, whirring flight, this is the most recognisable and popular of all North Atlantic seabirds.

Puffins spend most of the year at sea, but for a few months of the year the come to shore, nesting in burrows on steep cliffs or on inaccessible islands. Awe-inspiring numbers of these birds can sometimes be seen bobbing on the sea or flying in vast wheels over the colony, bringing fish in their beaks back to the chicks. However, the species has declined sharply over the last decade; this is due to a collapse in fish stocks caused by overfishing and global warming, combined with an exponential increase in Pipefish (which can kill the chicks).

The Puffin is a revised and expanded second edition of Poyser's 1984 title on these endearing birds, widely considered to be a Poyser classic. It includes sections on their affinities, nesting and incubation, movements, foraging ecology, survivorship, predation, and research methodology; particular attention is paid to conservation, with the species considered an important 'indicator' of the health of our coasts.

Puffins spend most of the year at sea, but for a few months of the year the come to shore, nesting in burrows on steep cliffs or on inaccessible islands. Awe-inspiring numbers of these birds can sometimes be seen bobbing on the sea or flying in vast wheels over the colony, bringing fish in their beaks back to the chicks. However, the species has declined sharply over the last decade; this is due to a collapse in fish stocks caused by overfishing and global warming, combined with an exponential increase in Pipefish (which can kill the chicks).

The Puffin is a revised and expanded second edition of Poyser's 1984 title on these endearing birds, widely considered to be a Poyser classic. It includes sections on their affinities, nesting and incubation, movements, foraging ecology, survivorship, predation, and research methodology; particular attention is paid to conservation, with the species considered an important 'indicator' of the health of our coasts.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER 1

Puffins and auks

The first detailed description of the Atlantic Puffin was made by John Caius in 1570. His original text was in Latin and the following translation is from Evans (1903): ‘There is a certain sea-bird of our country, in size and form of body like a little Duck with webbed and reddish feet, placed nearer to the hinder parts than in other web-footed kinds except the Pygosceles [penguins]: with a somewhat thin beak, rather more extended in breadth vertically than stretching laterally to a very great length, furrowed by four red grooves above, and two below, pale ochre in colour. The part lying between these and the head is bluish, and of such a shape as is the moon, when ten days have elapsed from conjunction. The bird is black on the upper surface of the whole body, save where the eyes are set, which are enclosed in white; but is wholly white below, save on the upper breast, where it is black. It gets its living from the sea. This bird our people call the Puphin, we say Pupin from its ordinary cry of ‘pupin’. It hides in holes in the ground … And so is driven out from a Rabbit’s burrow by a ferret turned in by any hunter in a place situated not far from the sea. It is used as fish among us during the solemn fast of Lent: being in substance and taste not unlike a seal. It is a gregarious animal, and has its proper time for lying hidden, as the Cuckoo and the Swallow. It lays for the most part two eggs in Rabbit burrows in the earth… I kept one in my house for eight months. It bit with right good will those who supplied it with food or touched it, but in a mild and harmless way.’

Caius was obviously familiar with the Puffin, although we now know that it lays one not two eggs, disappears out to sea outside the breeding season rather than hibernating and most people would consider its bite painful rather than mild. He sent this description and a drawing to Gessner who, in his Historia animalium (1551–58), changed it to ‘If you imagine that this bird was white, and had then put on a black cloak with a cowl, you would give this bird the name of Little Friar of the sea (fratercula marina)’. This upset Caius who considered it frivolous and struck the remark out of his own copy of that book (Nutton 1985).

Puphin, or some variant from the verb puff which means to become swollen, appears to have been used from at least 1287, although originally it referred to the very fat young shearwaters that were salted and traded as food. This explains the considerable confusion between the names of the puffin and shearwater (the French name for the Manx Shearwater is Puffin d’anglais and its scientific name is Puffinus puffinus). To add further confusion, in 1666 Merrett in his Pinax rerum naturalium britannicarum gives the Puphin as Puphinus Anglicus (Bircham 2007) and the Black Guillemot was sometimes known at the Puffinet (Lockwood 1984).

THE AUKS

The Atlantic Puffin and its sister species the Horned Puffin in the Pacific are perhaps the most widely recognised members of the auk family (Alcidae). There are no auks in the southern hemisphere, and conversely no penguins or diving-petrels in the northern hemisphere. The resemblance of the larger auks to penguins and the smaller auks to diving-petrels is due to convergent evolution, a process whereby taxonomically unrelated birds are moulded to a similar appearance by similar environmental pressures. Today, these groups of marine birds that both use their wings for underwater propulsion occupy similar ecological niches in the two hemispheres. However, no penguin has developed such an elaborate bill as a Puffin, although the crested penguins have gone in for flamboyant head plumes such as are found in some auklets.

The Atlantic Puffin is one of four species of puffin that belong to the Alcidae which include 23 living and one recently extinct species. Twenty-one species occur in the North Pacific, of which 17 are endemic. This compares with just two endemics in the North Atlantic – the Atlantic Puffin and Razorbill (three if we include the extinct Great Auk). Common and Brünnich’s Guillemots are common in both oceans but the Pacific populations of Little Auks and Black Guillemots are extremely small. The very rough population estimates suggest that approximately similar numbers of auks occur in the two oceans and the Atlantic Puffin accounts for the bulk of the world’s puffins.

EVOLUTION OF THE AUKS

Much has been written on the origin and evolution of the auks (e.g. Udvardy 1963, Bédard 1969). The early studies depended on evidence from morphology, fossils and biogeography but in recent years DNA analysis has allowed more objective judgments to be made (details in Pereira & Baker 2008). The Alcidae appear to have originated, and initially evolved, in the temperate or subtropical parts of the Pacific and only later did these early species become adapted to cold waters. Auks could have entered the Atlantic by either of the obvious Arctic routes around the top of North America and/or Eurasia after they became cold tolerant, or the now less obvious southern way before the uprising of the Isthmus of Panama prevented free movement between the oceans. Both routes were probably used, with the ancestors of Common and Brünnich’s Guillemots, Razorbill and Little Auk taking the southern route while the ancestors of Atlantic Puffin and Black Guillemot moved very much later via the northern route when the Bering Strait became ice-free during the Pliocene and Pleistocene. As suggested by the morphology of the birds and confirmed by DNA analysis, the Atlantic and Horned Puffins are much more closely related to each other than to the Tufted Puffin and Rhinoceros Auklet (Friesen et al. 1996). The separation of the Atlantic and Horned Puffins took place less than 5 million years ago; their ancestor diverged from the Tufted Puffin about twice as long ago and from the Rhinoceros Auklet six times as far back in the past. It is, however, hard to know whether the geographical isolation of the ancestors of the Atlantic and Horned Puffins resulted in the two becoming separate species, or if they were distinct before the Atlantic Puffin moved into the Atlantic.

Auks still move between the Pacific and Atlantic, albeit extremely rarely. Several Pacific species have been seen in the Atlantic or adjacent waters in historic times with records of Tufted Puffins in Maine (obtained and painted by Audubon), Sweden, south-west Greenland and most recently, off south-east England. A Parakeet Auklet has been seen in Sweden, a Crested Auklet off Iceland and a Long-billed Murrelet off southern England. Auks are resilient birds and it cannot be assumed that any individual that turns up in the wrong ocean is doomed to an early death. A single adult Ancient Murrelet, a widespread species in both the eastern and western Pacific, was present among other auks on Lundy, south-west England, during the summers of 1990–92 (Waldon 1994). Given the decreasing amounts of ice around the northern edges of North America and Asia it is probably only a matter of time before Horned Puffins reach the Atlantic or Atlantic Puffins reach the Pacific.

PUFFINS AS A GROUP

This book is concerned mostly with the Atlantic Puffin. However, for the sake of completeness brief summaries (from Gaston & Jones 1998, Piatt & Kitaysky 2002a, b) of the appearance, distribution and population sizes of the four puffin species are given below.

Atlantic Puffin

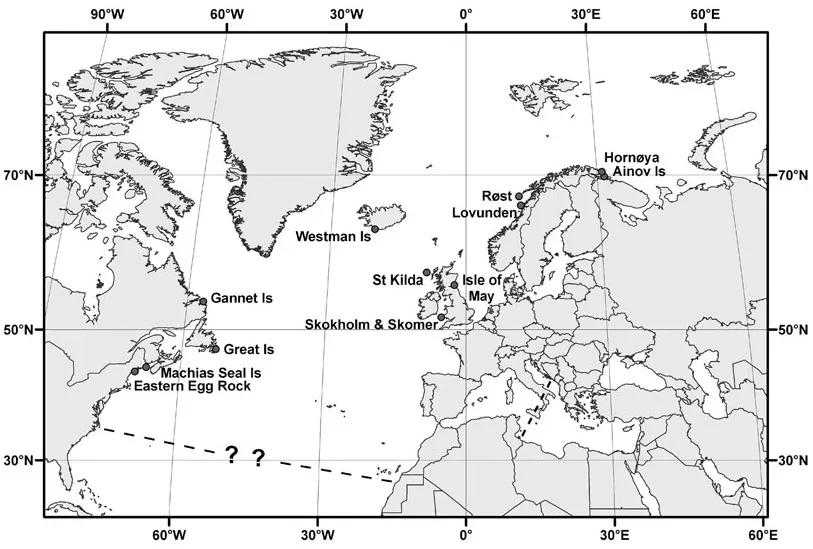

The Atlantic Puffin stands 18–20cm high and weighs 350–600g. It is black above and white below with large and well-defined white or grey face patches. The beak is large, laterally compressed and brightly coloured with a series of grooves in the outer part. A full description is given in Chapter 3. The Atlantic Puffin breeds from France and the Gulf of Maine in the south to as far north as there is ice-free land and has been studied throughout its range. It winters over vast areas of the North Atlantic and, in small numbers, the Mediterranean (Figure 1.1). It is the most numerous of the four puffins with some 20 million individuals. The single egg is incubated for six weeks and the chick is fed on small fish for another six weeks. The chick is independent after it has fledged.

Horned Puffin

Slightly larger than the Atlantic Puffin and weighing 500–650g, the Horned Puffin has blackish upperparts, white underparts and sides to the head, and a large, brightly coloured beak. The main differences between this species and the Atlantic Puffin are the pointed fleshy protuberances above each eye which point devilishly to the sky, and the inner two-thirds of the upper and lower bill which are creamy yellow, the outer part being red with the usual grooves. The legs and feet are orange.

Figure 1.1. The colonies where the major studies of Atlantic puffins have been carried out and the approximate southern limit of the distribution in winter.

Figure 1.2. The three puffins in the pacific – Tufted puffin (top), Horned puffin (mid) and Rhinoceros Auklet (bottom).

The species has a more northerly distribution than the Tufted Puffin, although the two species occur together over more than half the breeding range, breeding from the Arctic south to Japan and British Columbia. Most Horned Puffins winter well offshore in the central North Pacific. There are about one million individuals, with 86% in North America. The Horned Puffin generally nests among rocks or in cracks in the cliffs. The single egg is incubated for six weeks and the chick fed for another six weeks on fish and squid caught relatively close to the colonies.

Tufted Puffin

This is the largest puffin, standing some 30cm high and weighing 750–850g, and by far the most strikingly marked. The bird is all-dark, except in summer when the forehead and cheeks are white and there are spectacular long white or yellow tufts of feathers drooping down behind the eye and curling onto the shoulders. In the winter, the face becomes grey-brown and the plumes are lost. The legs, feet, eye-ring and bill are startlingly orange or reddish-orange, the base of the upper mandible is greenish and the outer part has several very distinct grooves which curve the opposite way to those on the bill of the Atlantic Puffin.

The Tufted Puffin is the commonest puffin in the Pacific with 3 million birds (82% in North America). Breeding colonies occur on both sides of the Pacific from the Arctic south to Hokkaido Island in Japan and to the warm waters of California. Wintering areas are located in the deep oceanic waters of the central North Pacific. Birds typically breed in earth burrows near the cliff edge, partly because it is easy to dig there and partly because these are the heaviest of the puffins and have difficulty in taking off from flat ground. The colonies are sometimes very large, with many tens of thousands of pairs. The biology is ‘typically puffin’ – a single egg incubated for six weeks and the young fed on fish and squid (sometimes caught well away from the colonies) for six to seven weeks before fledging, after when the juvenile is independent. Adults eat mainly squid and planktonic invertebrates.

Rhinoceros Auklet

Adults of this species weigh 450–550g and have upperparts that are sooty-black and a whitish belly. The upper breast, throat and sides of the body are brown-grey giving the bird a slightly dirty appearance. Its bill is not as flattened or as deep as other puffins nor does it have grooves, but in the breeding season it has a large ‘horn’ pointing upwards and slightly forward from the base of the upper mandible. The breeding plumage is completed by two sets of whitish plumes, one set behind each eye, the other just below the gape.

Rhinoceros Auklets breed in large colonies in two separate areas – the Gulf of Alaska south to California (where there are only a few hundred birds) and from the western end of the Aleutian chain down the coast of Asia to Japan. The total population is about 1.25 million breeding birds. It winters inshore, just to the south of the breeding range. Unlike other puffins, this species is mainly nocturnal at the colony, visiting its burrow, which is dug in soft soil among dense vegetation or in a cave, at night. Apparently, it is then safe from predatory gulls while crashing into, or floundering among, the bushes and tall herbs. The single egg is incubated for six weeks and the young fed at a lower rate than normal for the other puffins, so that it grows more slowly and fledges when seven to eight weeks old.

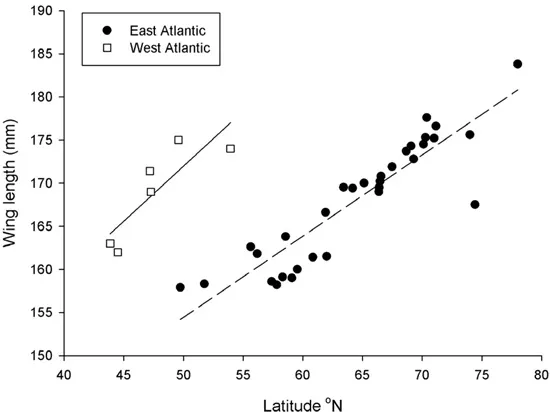

TAXONOMY OF THE ATLANTIC PUFFIN

Although the Atlantic Puffin breeds over a wide area, there are no obvious geographic differences in plumage. Birds in the north of the range are, however, large compared to those in the south (Figure 1.3). This latitudinal pattern is apparent in many taxa and is known as Bergman’s rule. On average, a Puffin in southern Britain has a wing length of 158mm and weighs c.400g whereas comparable measurements for a bird in Spitsbergen are 184mm and c.600g. However, there is considerable variation in the size of Puffins at any colony and some adults on the Isle of May are larger than the average at some colonies in northern Norway. It is therefore difficult to predict where any individual Puffin might have come from with any certainty. Puffins from western Atlantic colonies are generally larger than those from British and Faeroese colonies at the equivalent latitude. This is consistent with the idea that latitude is a proxy for temperature since conditions at similar latitudes are markedly colder in the west Atlantic compared to the east. One would expect cold-water Puffins to be larger than those in warmer climes since larger size reduces the ratio of body surface area to mass and so reduces heat loss.

Some birdwatchers and even serious ornithologists become upset if the name of a well-known bird is changed and mutter about ‘splitters’ (taxonomists who divide one former species into several new ones) or ‘lumpers’ (those who combine two or more species). They do not realise how lucky they are since, despite the current spate of changes resulting from the use of molecular techniques to detect cryptic species, ornithological taxonomy at the species level is now reasonably stable. This stability is, however, a recent phenomenon, and Fratercula arctica had many growing pains even after it was known that summer-plumaged and winter-plumaged individuals belonged to one species.

Figure 1.3. The increase in wing length of adult Puffins with latitude of the colony in the east and west Atlantic. Both relationships are significant (r = 0.91, p<0.001; r = 0.85, p<0.03, respectively). Sample sizes are given in Appendix 1. The outlying point in the east Atlantic is Bjørnøya at 75°N which is based on only six skins.

Until the 1960s it was generally agreed that there were three subspecies of the Atlantic Puffin that could be differentiated by size. These were the very large naumanni in the high Arctic, Spitsbergen, and north-west Greenland, the small grabae in Britain, Ireland, the Faeroe Islands, France, Channel Islands, southern Norway and, until the populations became extinct, Helgoland and Sweden, and the intermediate arctica of eastern North America, Iceland and most of Norway. The dividing line between grabae and arctica in Norway was taken as the 200km gap in the species’ distribution between Stavanger and Husøy, north of Bergen. Birds from Murmansk, Novaya Zemlya and Jan Mayen were difficult to assign to a subspecies being apparently intermediate between naumanni and arctica although some difficulties were due to only a few specimens being available. This situation took many years to sort out and some of the correspondence in the scientific literature, especially in the journal British Birds, in the early part of the last century was spiced with more than a little rancour.

When Linnaeus described the Puffin as Alca arctica in 1758 he failed to give a type locality, saying instead that it ‘lived in the Atlantic Ocean on r...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- Introduction and acknowledgements

- 1. Puffins and auks

- 2. Studies of Puffins

- 3. Appearance, development and moult

- 4. Distribution and status in Britain, Ireland and France

- 5. Distribution and status in Iceland, the Faeroe Islands, Norway, Russia, Svalbard, Greenland and the western Atlantic

- 6. Colony attendance and incubation

- 7. Chick rearing and breeding success

- 8. Puffin behaviour (by Kenny Taylor)

- 9. Food and feeding

- 10. Predators, pirates, parasites and competitors

- 11. Survival of Puffins and the Isle of May population

- 12. Puffins away from the colony

- 13. Puffins and people

- 14. Other threats to Puffins

- 15. Overview and the future

- Appendix 1. Measurements of Puffins throughout the range

- Appendix 2. Sources of counts and estimates and general background information used in Chapters 4 and 5

- Appendix 3. First and last dates of Puffins in Grampian, on the Isle of May and Fair Isle

- Appendix 4. Dates when Puffins were first seen on the sea and ashore and were last recorded ashore or carrying fish on Skokholm

- Appendix 5. Timing of breeding of Puffins on the Isle of May and the Farne Islands

- Appendix 6. Measurements of eggs of Puffins throughout the range

- Appendix 7. Annual peak and fledging weights, age at fledging and growth rates of Puffins on the Isle of May, 1974–2010

- Appendix 8. Breeding success of Puffins on the Isle of May, 1973–2010

- Appendix 9. Numbers of fish brought to young Puffins on the Isle of May, 1973–2010

- Appendix 10. Diet by weight of young Puffins on the Isle of May, 1973–2010

- Appendix 11. Lengths of sandeels, rockling and other Gadidae dropped by Puffins on the Isle of May, 1973–2010

- Appendix 12. Lengths of sprat, herring and unidentified Clupeidae dropped by Puffins on the Isle of May, 1973–2010

- Appendix 13. Annual mean weights of loads of fish, number of fish per load and frequency of feeds brought to young Puffins on the Isle of May, 1973–2010

- Appendix 14. Scientific names of birds, mammals and amphibians mentioned in the text

- References

- Plate Section

- Imprint

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Puffin by Mike P. Harris,Sarah Wanless in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Zoology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.