![]() Part One:

Part One:

Literary non-fiction![]()

1: Introduction

by Sally Cline

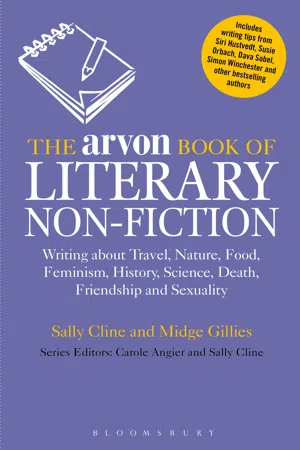

The plan of this book, like the plan of each book in this series, is based on the model of the UK’s Arvon Foundation for Writing.

Courses at Arvon traditionally have two established writers working together as mentors with both emerging and experienced writers, with many different writing genres ranging from short stories, through novels, poetry, TV and radio writing, biography, and memoir to general non-fiction.

Similarly, all the books in our series will have two writer-tutors and an exciting range of topics. The first two volumes (published 2010 and 2012) covered life writing and crime writing. Those that follow will include children’s fiction, historical fiction, short stories, television and radio, and novels.

In this volume on literary non-fiction, we have brought our different writing experiences and our complementary voices to the subject of literary non-fiction in its many forms. Among the areas we have chosen to cover are social and cultural history, nature, landscape, food, feminism, travel, social history, neuroscience, sexuality, death, and the mysteries of mind and body.

At the Arvon Foundation, the two tutors invite a guest midweek to add another voice to the writerly conversation. Again following the Arvon model we have invited thirty guests, each of them distinguished in their own area of literary non-fiction, to contribute their experiences and their talents in their own voices to our book.

Thus, we have travel writers, historians, landscape and nature writers, feminist philosophers, psychotherapists, novelists who write non-fiction and non-fiction authors who write novels. They will expand the conversation that is about to take place between the authors of this book and the readers and the guest writers participating in it.

Our book has the same three-part structure that all volumes in this series will have. Part One is devoted to the history, definitions and philosophy of literary non-fiction as well as to the challenges of writing it. Part Two is our Guest Section, where we can hear a wondrous variety of different voices. Part Three is practical, active and very much the readers’ section. It is a hands-on approach to planning, researching and writing literary non-fiction.

Part One: Literary non-fiction

We begin the first part of this section with several key questions: what does the term literary non-fiction mean? How does this genre differ from any other mode of non-fiction and especially from the prose called creative non-fiction? What is fascinating about genre-bending books? Why is it important that literary non-fiction writers show a respect for truth in its many forms? We then discuss how the concept of excellence lies at the heart of the mysteries of literary non-fiction. This is of course subjective, yet it contains essential elements many can agree upon.

We then move to an analysis of the challenges of literary non-fiction and how they can be overcome. We discuss the structural and ethical difficulties of this kind of writing, in particular the problem of who owns the lives of its subjects.

We ask questions about the re-creation of the past, how it can be achieved accurately and where it may lead. We are interested in the kinds of imaginative explorations needed to make familiar subjects jump up and seem strange and wonderful. Then we try to analyse the attraction and the difficulties of blurring the edges between non-fiction areas (for instance, books that are part autobiography, part travel, part philosophy). Having tackled the theory and the thorns, we then turn to non-fiction subjects which we find exciting. Midge explores in detail travel writing, nature and landscape, history in several forms; Sally immerses herself in feminism, food, friendship, sexuality, death and in parts of neuroscience and psychology that analyse the strange behaviour of our minds and bodies.

Part Two: Tips and tales

In Part Two of the book, our guests talk directly to readers. Thirty top non-fiction writers provide pithy, provocative and thoughtful pieces about their own craft. All thirty authors are among the very best and best-known writers in their field. They offer helpful hints on the writing game, their own despairs and joys, and the challenges that face us all.

Our contributors include those who enjoy the delights of nature and place, such as Richard Mabey, Jennifer Potter, Robert Macfarlane and Barry Lopez. We have biographers such as Philip Hoare and Diana Souhami, who stretch the boundaries of non-fiction in diverse directions to weave together fact, fiction, autobiography, history, literature, natural science, humour and danger. We devote a whole section to food writing and have invited, among many possible food writers, the historian Lizzie Collingham to talk about the complexities of her craft.

We have gathered feminists from across the globe to challenge received opinion in their writings. Australia’s Dale Spender joins the UK’s Susie Orbach, Natasha Walter and Bidisha, who use their individual expertise in psychotherapy, analysis, broadcasting and digital media to throw light on contemporary sexual politics.

Travel authors form a strong part of this section. They range from Colin Thubron to Sara Wheeler and Rosemary Bailey. Yet none of them is a straightforward travel writer: their books are also memoirs, or philosophical essays, or even dramas with foreign characters and strange riveting plot lines.

The genre of literary non-fiction is home to a number of diverse modes of scribbling,, and we have novelists who write non-fiction and non-fiction writers who write novels. Siri Hustvedt, a witty and revelatory novelist, writes an equally powerful neurological memoir.

If the quintessential element of literary non-fiction is the mixture of originality and imagination, then writers Francis Spufford and Dava Sobel beautifully embody it. Both endow their works with significant themes and a happy fusion of styles. And we have the wonderful storyteller Simon Winchester, whose subjects have included a book about a madman, a publisher and a dictionary, and a biography of an ocean in Atlantic.

Part Three: Write on

Here we stop talking and invite you, the readers, to participate in some hands-on work. We offer a selection of chapters containing creative exercises alongside practical advice. We have divided the section into three parts: planning, researching and finally writing the book.

Under Planning, we look at structure, format of books, prologues, prefaces, bibliographies and indexes, as well as how to use and indicate referential material.

Under Research, we talk about internet research, libraries, archives and interviewing, and wrestle with that tough question of when it is time to stop researching and start using the keyboard.

The Writing section includes exercises, illustrations and top tips for most of the points given in the book: for instance, on interviewing; on description, quotes and dialogue; on the use of fictional techniques; on how to achieve a balance between facts and artistic truths.

![]()

2: What is literary non-fiction?

by Sally Cline

What is literary non-fiction? It is rainbow-hued and many-splendoured. It can be a book about the Arabian Desert or the exquisite sluggishness of the sloth. It can be a book devoted to the differences between shaved ice and hot oatmeal in this culture or another far away. It can express feminist excitement and rage or it can be about understanding badgers or standing up to sharks. It can help us understand the wonders of neuroscience or the history of antiquities.

It can be about anything writers of non-fiction can dream of, but it has to have the stamp of literature.

Any non-fiction book will contain one riveting element to pull readers in: the fact that it is about something that actually exists or actually happened. Readers want to know about real lives and real events, especially those that are not our own, indeed are unlike our own. They want to know about other places, foreign travel, different landscapes. Readers want to know which trees grow where, what happened in a particular historical period, how we can unearth the mysteries of body and mind. Non-fiction books can provide fascinating information on social or political groups, cultures, philosophies. What is Buddhism? How does feminism work today? Why do we eat what we eat, whereas people in other lands eat unbelievably different foods? I remember feeling queasy when my friend told me she had been served goat stew at a British dinner party. If she had said she had eaten it in Morocco or the Caribbean I would have been less surprised, though I would still have felt peculiar. I have to say that I am a long-time vegetarian, so English Sunday roasts, American chilli hotdogs, barbecued alligators or Texas turkey turnovers do not thrill me. But they do interest me, because they are not matters of invention but matters of fact.

The importance of non-fiction to readers is exactly that. We do not need to suspend our disbelief; what we are being told is true. Or so we hope and believe. The version in print or on our Kindles may not be totally accurate, but generally readers assume that non-fiction authors believe their accounts are true, or at least were at the time of writing. Most writers also believe that, indeed strive towards that. If we are invading the territory of the family, ours or other people’s, we need to be even more careful. One area of literary non-fiction, that of life writing, is particularly vulnerable to this problem. The challenge of what is ethical as well as what is ‘true’ is always there.

Often the non-fiction material most of us write will include a clear and balanced argument. Traditionally, our general purpose is to be simple, clear and direct. There are some non-fiction writers who use supposition or their imagination to smooth out their narratives. On occasion I have done this to good effect; but for many non-fiction readers brought up to respect a straightforward classical style and tempo, the use of literary techniques in fiction may appear inappropriate. This certainly has been true in the past, although today matters are changing.

There have always been genre-bending books in literary non-fiction, such as A.J.A. Symons’s The Quest for Corvo and the works of W.G. Sebald, which successfully blur the boundaries between fact and fiction.1 Jonathan Raban’s Coasting: A Private Voyage about a voyage round Britain in a two-masted sailboat, partly a seafaring tale, partly a memoir, partly a novel, successfully blends a journey-narrative with a discussion of the history of the sea. Another exceptional example is Leviathan by one of our guest writers Philip Hoare, an amazing feat which blends memoir, social history, biography, literary criticism and nature writing.2 These are all works of imagination and indisputably works of non-fiction literature.

We would suggest that a non-fiction work is creative if it conforms to the fundamental requirements of respect for truth, but also results from originality of thought and expression. To be considered, in addition, literary, the work must possess the key characteristic of literature, which is writing that has permanent worth through its intrinsic excellence.

Central to the concept of excellence is the use of fine and polished language, which will show mastery of imagery, texture, colour, word choice, rhythm and voice. Literary non-fiction writers will also offer a way of looking at the world, as well as serious research, which makes the content credible and helps shape the material.

Useful examples of what is literary non-fiction and what is not can be found in food writing, as I show in a later chapter in this book. I single out the differences between engaging but non-literary food writers who offer good recipes and anecdotes about culinary procedures, and imaginative literary food writers – for example Muslim or Jewish writers who imbue their material with the culture, religion or ethics of the society from which that food stems. Their research offers us a new world in which to feast, in which to delight.

Sometimes excellence in non-fiction literature can include the management of fictional devices such as suspense, a compelling narrative or a story arc. Where this takes place the writer deploys description, conflict, change and resolution in the manner of the classic short story. The challenge for these writers is that, while using the relevant fictional tools, they must always remember that at the heart of their prose must be truth.

The best literary non-fiction dwells among lasting themes, and offers a sense of the profound in which the subject stands for more than itself.

A good example is Barbara Ehrenreich’s witty and thoughtful Smile or Die: How Positive Thinking Fooled America and the World. On the surface this is a sharp, often brutal attack on the ‘have-a-nice-day’ greeting which has permeated American life.3 Ehrenreich’s style is not dissimilar in places to that used in the later New Journalism and in the best creative non-fiction. What separ...