![]()

Part One

Socio-political Undercurrents

1

Facts, Figures and Guesstimates

The impression is sometimes given that civilian evacuees from Burma were relatively few in number and mainly British by nationality. The statistics tell a different story. The evacuation was a mass movement and most of the evacuees were Indians. In normal circumstances the most recent census would be the starting point for an analysis of sections of a colonial population. Every ten years, British authorities counted, measured, weighed, compared, analysed and recorded their colonial subjects in every corner of Empire. However, there was nothing normal about Burma in 1941. The raw data for the census of that year went up in smoke in a Japanese air raid. The statistics relating to the population, its profile, size and racial composition, where people lived, what work they did and their ages were all destroyed. The Census in 1951 did not take place, so it will never be known how the population changed during the war.

The most recent reliable information available was provided by the 1931 Census.1 The total population of Burma in that year was 14,647,497, of which 1,017,825 were Indians. Seventy-five per cent of all Indians were males and 63 per cent had been born in India. The combined total of Europeans plus Anglo-Indians and Anglo-Burmans was 30,851.2 Because Anglo-Indian and Anglo-Burman often took European names, the Census Superintendent confided that up to 3,000 or 4,000 Anglo-Indians might have been wrongly designated as ‘Europeans’.3 Be that as it may, 11,651 Europeans were recorded as resident in Burma in 1931. Only 6,426 of them had been born in Great Britain and Ireland. These totals were consistent with previous censuses.4 A steady stream of Europeans had left Burma in the months preceding the Japanese invasion, so the European population in Burma had probably decreased by the beginning of 1942. At the same time (and for the same reason), the Indian population had probably declined as well.

The occupational statistics in the Census for 1931 contained few surprises, except perhaps that only 365 Europeans were described as public administrators. This confirmed the view that before the war a very small number of British officials had governed the whole of Burma. On the other hand, 1,594 of the Europeans held senior positions in the law, medicine and engineering. About the same number were in the ‘liberal arts’, most of them teachers and missionaries. A further 3,821 were identified as managers, industrialists, technicians and businessmen; 1,638 were in the Army and 1,793 were in the ‘public force’ (police, jailers, etc.). By contrast only 26 Burmans were in the Army and 10,576 were in jail. The majority of medical practitioners, policemen, railway employees and soldiers were Indians and very large numbers of Indians were traders and ‘producers of raw materials’.

Three conclusions can be drawn from these figures. First, the ratio of Indians to Europeans living in Burma in 1941 was probably about 130:1. Second, fewer than 12,000 Europeans lived in Burma at any one time. Third, even if the exact population of Burma in 1941 was known, it would still be impossible to deduce how many of them became evacuees in 1942.

* * *

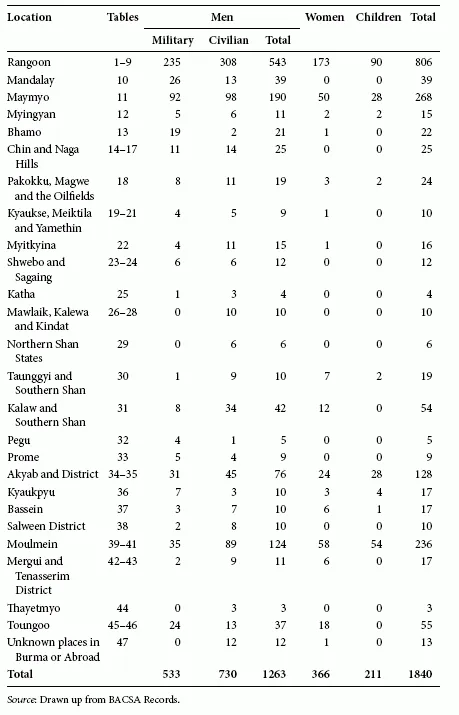

Two other statistical sources shed light on the European population at the time. The first was the British Association for Cemeteries in South Asia (BACSA) Register of Deaths and Burials. Britons who died in colonial Burma were almost always buried in European cemeteries. The Public Works Department (PWD) and local churches kept these cemeteries in good order before the war, but after the war most of them fell into disrepair. Cattle grazed among vandalized headstones and some cemeteries reverted to jungle. In the nick of time, BACSA stepped in to draw up the Register of Deaths and Burials (Table 1.1). It casts further light on pre-war colonial society in Burma.5

Climatic conditions, poor sanitation, limited health provision and frequent outbreaks of violence, all contributed to the high mortality rates among the 12,000 or so Europeans normally resident in Burma during the twentieth century. The BACSA records bear witness to conquest, epidemics, floods and rebellions, and provide details of nearly 2,000 Europeans buried in Burma between 1682 and 1948.6 They include 1,263 men (533 military and 730 civilians), 366 women and 211 children. Most of the deceased were buried in Rangoon (806), Maymyo (268), Moulmein (236) and Akyab (128).7 Some of the most poignant memorials were the most recent, none more so than the monument erected at Thanbyuzayat to the 3,771 Prisoners of War (POWs) who died while constructing the Thailand to Burma Railway. At the other end of the scale, the BACSA Register records hundreds of individual tragedies – the deaths of infants, teenage girls, young wives in childbirth and of the many young men cut down in their prime. Tropical disease, unclean water and heat were usually to blame. The Europeans’ average age at death was 38.

Table 1.1 Register of European deaths and burials

The deaths recorded during, before and after 1942 challenge the assumption that all colonials were strapping young men. Many European women had gone to live in Burma, and by the 1930s and 1940s several Europeans had become elderly and infirm. Take the European cemetery in Maymyo, for example; 16 of those buried were in their sixties, 13 were in their seventies and 11 were in their eighties – Elizabeth Shephard (80), Lieutenant Commander Stanley Higgins (81), Eric McColl (81), Laura and James Gahan (both 82), Frederic Griffiths (83), Edward Richardson (84), Charles Edward Court (86) and A. E. C. Walker (89). Frances Lutter was 96 and Henry Lutter died at the age of 100. Nor was Maymyo unique. Two 99-year-old Europeans (Dr Charles Lawrie and William Smith) died in Kalaw in the late 1930s. Burma was obviously not just a place of work for Europeans; it was also a place for retirement. It would be safe to assume that a good number of elderly Europeans still lived in Burma in 1941 and that many of them had to be evacuated in 1942. Indeed in 1942, 188 of those listed in the BACSA Register were aged 60 or more and 41 of them were over 80 years of age. The not insignificant geriatric element in the population must have added to the evacuation organizers’ difficulties.

At the other end of the spectrum, in the BACSA Register, 110 European infants are recorded as having died before their first birthdays. It goes without saying that many more infants lived than died during the early 1940s.8 Soon after the evacuation, Reginald Clarke wrote home to tell his wife that Muriel Horrocks had had a son on 23 December, that Joan Robertson had had a third son in November, that Billie Hughes was having her first child, that Mrs Marsden-Ranger had had a daughter and that Mrs MacWhite was about to have her first child. It prompted a friend, Mrs Beryl Parry, to remark that Burma must have been ‘a very relaxing place’.9 Of course, scores of infants and nursing mothers heaped more logistical difficulties on the Evacuation Department.

The Register highlights another problem. The European population in Burma was widely scattered. Although most of them lived and died in the major conurbations of Rangoon, Mandalay, Maymyo, Moulmein and Akyab, others were buried in 30 different cemeteries scattered around the country. Each of these cemeteries served as a hub for a far-flung hinterland in which lived tiny communities of Europeans.10 Gathering these people together in 1942, transporting them and monitoring their movements were very difficult tasks.

The BACSA Register recorded the circumstances of many of the deaths that occurred during and immediately after the evacuation. Raymond Hall, an Assistant in the Steel Bros Timber Department was one of the earliest European casualties of the war. He was killed on 20 January 1942 when Japanese troops overran his outpost in south-east Burma. He was buried in Kawkareik. J. G. Fielding-Hall was buried in the Pegu cemetery in March 1942. He committed suicide in Prome after being blamed (quite unfairly) for the premature release of prisoners and ‘lunatics’ in Rangoon a few weeks earlier. Japanese soldiers shot G. G. Evans of BBTC in Prome in March 1942. He was also buried in Pegu. William Michael Van Wyck (Burma Civil Service, Class 1) was buried in Akyab in February 1944. He was killed while gathering intelligence in Arakan. Two employees of MacGregor & Co., William Nimmo and E. McGrindle were both killed by the Japanese after being parachuted behind enemy lines in 1944. They were buried in the Papun cemetery. J. Cook of the Burma Agricultural Service was buried in the Toungoo cemetery. Japanese troops shot him while he was working for CAS (B).

The deaths of several ‘last ditchers’ are recorded in the BACSA Register. These were men who courageously stayed behind to implement the government’s scorched earth policy. For example, D. H. Hutchinson, a BOC superintendent died of heatstroke while demolishing the Chauk oilfield on 18 April 1942. Brigadier F. A. G. Roughton CBE who liaised between the Army and the Oil Companies also died of heatstroke at Yenangyaung during the demolition in April 1942. Roughton was a retired Indian Army officer in the Burma Frontier Force and he had been ADC to Dorman-Smith.

D. K. Milligan of the Burma Forestry Service was killed in late 1942 and was buried in the Chin Hills. R. W. H. Peebles of the Burma Civil Service, Class 1, was killed in a motor accident while evacuating from Falam. Captain P. R. S. Banks, MC, of BBTC was accidentally shot and killed by his own sepoys while escaping on 28 November 1943. Two other employees of the Imperial Forestry Service – G. F. Ball MC (in May 1942) and J. H. MacKay (early in 1943) – were killed during the evacuation and buried in the Falam cemetery. Jules Martin, who was a Roman Catholic priest-cum-trader, was murdered by the Japanese. He was one of several Europeans buried in Mandalay cemetery in April 1942. Most of the others were killed in the air raid of 3 April 1942. Among the air-raid victims was Major Mills, the Senior River Pilot from Moulmein. Two ‘old Burma characters’ survived the War. One was Rev. W. R. Garrad, who was in charge of the Winchester Mission in Mandalay. He escaped from the city in 1942 and returned to Burma in 1945. He died in Rangoon in 1951 and was buried in Mandalay. Eric Gordon MacColl was born in Maymyo in 1892 and lived most of his life there. He was an artist and in 1942 was accused of kicking a Japanese officer (and he probably did). He was interned from 1942 to 1945. After the war he continued to live reclusively in a dilapidated hut in Maymyo until his death in 1973. He was buried in Maymyo cemetery.

* * *

The second source of information is a little more obscure. Although Who’s Who in Burma (1927) was well past its sell-by date in 1942, it still sheds light on the mores of Burma’s ‘elite’ on the eve of the evacuation. Of the 452 entries in Who’s Who, 168 were Burmans, 124 Indians, 98 British and 39 Chinese. Indian ‘Owners/Directors and Proprietors’ (with 37 entries) outnumbered all the other ethnic groups including the British. There were also many more Indian contractors, bankers, moneylenders, merchants, barristers, physicians, surgeons and general practitioners than those in any other single ethnic group. It is a timely reminder of the significant numbers of very wealthy Indians who lived in Burma.

Who’s Who reveals that a smattering of the wealthiest Indians lived in Mandalay, Maymyo and other towns, but the overwhelming majority (53) lived in Rangoon. Money did not necessarily buy social position in pre-war Burma. Even the wealthiest Indians were excluded from the European Pegu Club and Gymkhana Club and had to make do with the Orient Club. Many of the leading Indian businessmen were not university-educated, but those who were, attended Calcutta or Madras universities. A steady trickle had also begun to find their way into English and Scottish universities and to London Inns of Court. By contrast, 36 of the British entries were First Division Government Officials and 11 were High Court Judges. Almost all of them lived in Rangoon, 27 were members of the Pegu Club, 39 had attended English public schools, 28 were educated at Oxbridge and 22 had been decorated in the First World War. It would be fairly safe to assume that not much had changed in the intervening 15 years between 1927 and the civilian evacuation in 1942.

Wealthy well-educated Indians at the top of the social pile had little in common except for their ethnicity with the coolies and sweepers at the bottom of the pile. During the evacuation the Indian elite used to resent the way in which British officials insisted on lumping all Indians together. They frequently complained about discrimination. Many of them left Burma in privately chartered transport precisely to avoid having to mix with their low class, fellow countrymen. Yet, even during the worst moments of 1942 when all refugees of whatever colour were struggling for survival, British and Indian evacuees rarely rubbed shoulders. Despite protestations to the contrary, the British continued to erect barriers designed to separate them from Indian evacuees. It was somewhat ironic that after 1942 the Indian and European elites sank together. Only four European names and one Indian name featured among the 448 entries in the 1960 Burma Who’s Who. The evacuation delivered a deathblow to Indian and European communities alike.

* * *

A consensus had begun to emerge during the course of 1942. Newspapers and commentators alike seemed to accept that about half-a-million evacuees had escaped to India in 1942 and that about 80,000 of them had died on the way. Both sets of figures may have been ‘guesstimates’. They may have been plucked out of the air for propaganda purposes. For, by exaggerating the number of people who had supposedly escaped from Burma, and by underestimating the number who died on the way, the authorities gave impression that the evacuation was better managed than it really was. It became a case of authentication by repetition.

The ‘numbers game’ had begun very early. In January 1942 Sir Reginald Dorman-Smith announced to the press that about 200,000 people had already left Rangoon. O’Dowd Gallagher (a sensationalist war reporter) challenged the figure, saying that it ‘was nearer 300,000’.11 In April 1942, Reuters, which collaborated with the British Government, reported that ‘about 500,000 refugees’, that is, nearly half the entire Indian population in Burma, ‘had now arrived in India’.12 At the beginning of May 1942 the Indian Overseas Department issued a press statement saying that at least 250,000 of the 1 million Indians living in Burma had now been evacuated.13 The claim was repeated almost word-for-word on 1 May 1942 in a telegram from the Governor-General of India to the Secretary of State in London. In it he said that between 250,000 and 300,000 of the 1 million or more Indians living in Burma had been evacuated to India by sea, air and land.14 Four days later, the Ministry of Information in London declared that by the beginning of March 1942 about 300,000 Indians had already evacuated to India, and that others were now ‘crossing the frontier at the rate of 2,000 a day’.15 In a telegram of 9 June 1942, the Viceroy of India stated that about 400,000 Indian evacuees had arrived in India by the end of May.16 It is noticeable that very little was said at the time about the death toll among the evacuees. Indeed it was barely mentioned afterwards, and remains one of tho...