![]()

PART I:

QUESTIONS

LOGOS

1

SAYING WHAT ONE SEES, LETTING SEE WHAT ONE SAYS: ARISTOTLE’S RHETORIC AND THE RHETORIC OF THE SOPHISTS

NARCISSUS AND ECHO

In the Metamorphoses (III.339–510),1 Ovid retells the story of an ancient Greek myth. There once was a newborn unparalleled in beauty, who was named Narcissus by his mother, a river in Boeotia. To see if her son would live a long life, she went to find Tiresias, who had just been blinded by Juno and who had been given the gift of clairvoyance by Jupiter in exchange. This was Tiresias’ first prophecy. In response to the mother’s question about her son, Tiresias said, “if he does not know himself,” thereby reversing the imperative engraved on the pediment of the temple of Delphi, the “know thyself” that has been so endlessly interpreted in Western philosophy since the age of the Seven Sages and Socrates up through Hegel, or Freud. When Narcissus was an adolescent, men, women, and nymphs alike were smitten with him. But the nymph Echo was the most in love of all. She was an odd nymph—nothing but a body and a voice—for she had been punished by Juno in accordance with her sin: Echo knew all too well how to chatter, “to babble,” in order to detain Juno and prevent her from catching her husband, Jupiter, while he was adulterously caressing other nymphs. As punishment, Juno condemned Echo to “a diminished power of language” and to having only “very brief usages of her voice” (367). Echo therefore could do no more than “repeat the last sounds at the end of someone’s speech, and reproduce the last words she had heard” (368f.). Echo the “résonable”2 (358): speech without creativity, cut off from any intention to signify, talking of nothing and to nobody; speech that does not even contain a complete sentence or a repetition of what was first said, but that simply duplicates sound waves. Echo, the misery of speech that only refers back to itself, loves Narcissus and follows him everywhere.

During a hunt, Narcissus found himself alone, separated from his friends. He called out, “Is anybody there?”—“Anybody there,” Echo responded. “Come out,” he said—“Come out,” she replied. “Come out here”—“Out here.” But as soon as the nymph came out from the thicket to embrace him, he pushed her away and ran off. She dried up from hopelessness: there was nothing left of her but “a voice and bones” (398), which took, they say, the form of a stone. “Sound is what lives on in her” (401).

Narcissus was cursed by all the admirers whom he disdained.

Eventually, Vengeance led him to a spring of undisturbed purity. We know the rest: that “as soon as he wanted to appease his thirst, a new thirst was born” (415); he “contemplated” (420) what he saw there with an “insatiable look” (439); “he was captivated by the image he saw” (416); “he was mirrored and admired himself” (424). But this perfect lover who smiles when Narcissus smiles, who holds out his arms when he holds out his arms, is only a “fleeting simulation” (432), a “shadow” (434), a “lying form” (493). Narcissus, when he finally understood that “I am he” (463), dried up in turn and “himself died on account of what he had seen” (440). “Goodbye,” he said to his image. “Goodbye,” responded Echo, while in the place of his extinguished body the poet’s flower began to grow.

Narcissus: the simple look that only sees itself, sight reduced to the worst of seeing—the simulacrum. Echo: the simple voice that only repeats itself, speech reduced to the worst of speech—to sound. Narcissus and Echo miss each other eternally and die desiccated: sight and speech, obscured in this way, are untenable, and slowly die without each other.

There is a philosophical term that serves as a counter-poison to the myth, and gives a name to the interlacing of speech and sight, the wedding of Narcissus and Echo. For Martin Heidegger this term bespeaks the essence of ancient Greek philosophy: “phenomenology.” I would like to begin with this term, taken from the Heideggerian reading of Aristotle—but not to dwell upon what is evidently central to metaphysics and thought; rather, to find the motive that leads outwards, which in turn shall lead me toward sophistry. Sophistry: a way to think the echo philosophically. Herein lies the paradox of my project: in taking up the theme of “the places of seeing,” to speak of the one who, Plato said, “will appear to you as someone . . . who has no eyes at all” (Sophist, 239e).

SAYING WHAT ONE SEES: ARISTOTLE’S PHENOMENOLOGY AND THAT OF THE SOPHISTS

NOTIONS OF PHENOMENON AND PHENOMENOLOGY: AN ULTRA-HEIDEGGERIAN GREECE

As Heidegger remarks, even if the term “phenomenology” does not appear historically until the eighteenth century (in Lambert), in its historicity it is Greek: phainomenon, the middle participle of phainō, “that which shows itself, by itself, from itself,” and logos, “to say.” In paragraph 7 of Being and Time, Heidegger reminds us that phainō comes from phōs, “light.” Though even here, to tell the truth, there is already a tightly drawn etymological knot. Chantraine points out that phainō comes from the Sanskrit radical bha, which has a built-in “semantic ambivalence” because it signifies both “to illuminate, to shine” (phainoi, <phami>) and “to explain, to speak” (phēmi, fari in Latin). In other words, there is already a belonging together in bha of the sayable and the shining; there is already phenomenology in the phenomenon itself.

Finally, phōs, the same word as “light,” but with the acute accent instead of the perispomenon, designates as well (e.g. in Homer) man, the hero, the mortal. Chantraine tells us that the etymology here is somewhat “obscure.” However, “if the modification of the dental consonant is secondary, there is a formal identity between the Greek nominative and the Sanskrit bhas, meaning light, brightness, majesty”; “but,” he adds, “from a semantic point of view, the identification is troublesome.” Phenomenologically, on the contrary, it is too good to be true: etymological evidence that unifies “to appear,” “to say,” and “man.” The man of ancient Greece, that is to say man as such, is the one who sees light as a mortal (the light of the day of his birth, and of the return, death). He sees that which appears in the light, phenomena, and that which illuminates phenomena in saying them.

Here we find a matrix of the common perception of Greece, at once classical and Romantic, and motivating Heidegger’s interest: if truth is the belonging together of appearing and saying in human Dasein, at once openness and finitude, then truth is both the tracing of and the meditation on this etymology.

THE PHENOMENOLOGICAL CHARTER: ARISTOTLE, DE INTERPRETATIONE 1, 16A3–8

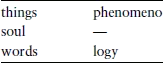

De Interpretatione deploys, in its very first lines, the classical structure that informs phenomenology and remains the great charter of language:

That is:

There is phenomenology, therefore, in the mediation of the soul allowing a passage from things into words:

Phenomenology appears very well as a question of transitivity; the phenomenon shows itself in language and lets itself be written and spoken on a double condition: that it “passes” into the soul, and that the soul “passes” into the logos.

However, this double condition constitutes a double problem as well: are we sure that the mediation of the soul does not obscure anything, and in turn, that the mediation of logos does not skew the affections of the soul? For the purpose of exposing “the phenomenological method” of his research, Heidegger proposes an exploration of the concepts of phenomenon and logos in paragraph 7 of Being and Time, winding up with a “provisional concept of phenomenology,” in order for the reader to progressively shed his or her classical prejudices and arrive at an understanding of the term that is more Greek, and more Aristotelian. Nevertheless, as we shall see, it seems just as possible to follow such a line of inquiry backwards in the opposite direction: we have to admit then that this phenomenological structure is, always already, and already in Aristotle, covered over and layered in and as the constitution of objectivity. In other words, transitivity in the end is only the guarantee that turns showing into a sign, logos into a judgment, unveiling into correspondence, and the phenomenon into an object. Is a Greek phenomenology, in spite of being the paradigm of phenomenology, unobtainable?

THE MUTE PARADISE OF PHENOMENONOESIS

In the best of all possible phenomenological worlds, transitivities would go without saying. In fact, Aristotle expressly assures us of the first one, the passage of the phenomenon into the soul, though under certain conditions. De Anima (III, 427b11) in effect stipulates that “the sensation of proper sensibles”—the “proper” sensible being “that which cannot be perceived by any other sense” (II, 418a11)—“is always true.” It is precisely on this point that Heidegger comments when he wants to push aside modern misinterpretations of the Greek concept of truth:

But, as soon as the mediation of the soul does not skew anything and transitivity is assured by an apprehension without detour, this truth that is always true...