![]()

Chapter One

What are opposites?

1.1 Introduction

This study is a contribution to the body of knowledge about what are popularly called opposites and sometimes also labelled antonyms or binaries. I will refer in general to such pairs of lexemes (and later, also to pairs of phrases or even clauses) as opposites, though I will also use a range of more specific terms for different kinds of opposites. The phenomenon of their particular semantic relation will most often be referred to as opposition. The main studies of opposition in linguistics have traditionally been in the area of lexicology and semantics, though as we shall see there is a small but growing number of studies investigating opposites in context. My main concern will be with pairs of words whose oppositional relationship arises specifically from their textual surroundings, which I am naming constructed opposites, created opposites or unconventional opposites interchangeably, but which have also been variously called non-systemic semantic opposition (Mettinger 1994:74), and non-canonical antonyms (Murphy 2003:11 and Davies 2008:80). This book will introduce and explore the phenomenon of the textually constructed opposite relation, initially formally and functionally, and then by a series of case studies which will consider its implications for ideological and aesthetic meaning in texts and their contexts of production and reception.1

It is important to recognize at the outset that this study relies to some extent on the acceptance of some kind of lexical semantics which hypothesizes that in addition to the cognitive storage of items (lexemes) and rules for their combination (morphology and syntax), human beings also have certain kinds of knowledge about the meaning (sense) relations between these lexical items. Thus, one of the things that we may know about the word hot in English is that it is opposite to the word cold, and more extreme in relation to temperature than the words cool and warm. There have been many developments in linguistics since de Saussure made explicit his ideas on the internal structure of human languages, and many of them have challenged the fundamental distinction between langue and parole, later adapted by Chomsky as a cognitive distinction between competence and performance. Nevertheless, one of the conclusions of this book will be that in order to explain the cognitive aspects of opposition-creation in texts, we will need to refer to at least some kind of core concept of oppositeness and its realization in lexical relations. This context-free notion of the capacity of words (lexemes) to be related by oppositeness will be referred to below as ‘conventional’ opposition, to reflect the idea that although there is nothing intrinsic about these relationships, and their importance may vary between languages and cultures, there is nevertheless some kind of tacit agreement between members of speech communities that certain words are formally opposite to each other. This is reflected, of course, in the importance that opposites are accorded in our culture in early education as evidence by the plethora of early books aimed at teaching pre-literate toddlers the core opposites.

I was first alerted to the contextual creation of opposition by an election slogan of the Conservative Party in the 1983 British election. There was a picture of a black man2 with a slogan underneath reading as follows:

Labour says he’s black. Tories say he’s British.

The parallel structure of the two clauses in this slogan (X says Y is Z) together with the conventional opposition between Labour and Conservative in Subject position (X) and identical content in the opening of the subordinate clause (he’s) sets up the expectation of a balancing pair of opposites as the two subordinate Complements (Y). What we have as a result is black and British being constructed as a pair of opposites by the advert. The implication is apparently that if the Labour Party calls a man black, they are denying his Britishness. This is therefore a complementary opposition; it is implied that you cannot be both black and British. This opposition appears to confirm the Conservative Party as one that is non-racist, since they are presented as ‘colour blind’ and those voters who are looking for that message may thus see them as emphasizing the inclusiveness of their definition of British. But the very creation of the complementary opposition black-British in itself indicates a potential to see these qualities as incompatible (you can’t be British if you do identify yourself as black) – and therefore feeds the prejudices of the racist potential voters too. Here is one (black British) reader’s response to this slogan:

In case I was in any doubt as to what this new black Briton looked like, in 1983 the Conservative party produced an advertisement that featured a photograph of a smartly suited, briefcase-wielding, well-groomed black man under the heading ‘Labour says he’s black, Tories say he’s British.’ Unsurprisingly, this black Briton neither looked like me, nor, in fact, did he look like anybody I knew. The Conservative party was soon forced to withdraw this advertisement, after it was pointed out that the terms ‘black’ and ‘British’ were not, in fact, mutually exclusive. However, at least we non-white Britons had been afforded a glimpse of one of ‘their’ images of ‘us’. (Phillips 2004)

Caryl Phillips naturally assumes that the Tory advertisement indicates that black and British are opposites, though the intention may not have been this in fact, and the Conservative Party might use the defence that this is not explicit in the text itself. In fact, the creation of opposites in such contexts is an example of what Grice (1975) calls a conventional implicature and Simpson (1993:127–8) calls pragmatic presupposition. This, they claim, is the creation of a presupposition or implicature not through the context-free text, but through the text in combination with its context of use. The juxtaposition of two words such as black and British in parallel structures of this kind and with conventional opposites in the Subject position of each of the parallel structures predisposes the reader to see the words as a pair of opposites. The actual interpretation of this text will depend on the reader, and Caryl Phillips as a black man on the left of the political spectrum naturally assumed that it was the Conservative Party who were racist in proposing this opposition, although their intention was to persuade readers that the Labour Party are more prejudiced because of their insistence on referring to people’s skin colour. However, the advertisement was presumably not aimed at those who would never vote Conservative, such as Phillips, but rather at those on the left of Conservative supporters who might have been looking for reassurance that the Conservative Party at the time (1983) was minimally not racist (i.e. was colour blind) and also conversely those on the right who were looking for reassurance that the Conservatives were indeed illiberal in their immigration policies (i.e. those who would accept that black and British are opposites).

Although presuppositions, even pragmatic ones, might be quite difficult to deny, it is always possible, with some effort, to ‘defease’ them (see Simpson 1993:134–8) and it is easier with pragmatic than with semantic presuppositions. Defeasing usually takes the form of denial and re-wording of the offending utterance. Here, then, this defeasing might take the form of the Conservative Party saying that they were simply trying to point out that they were more inclusive than Labour, since they accepted all kinds (colours) of people in the category ‘British’, without the need to point up the differences within that category. Indeed, even an interpretation of oppositeness really ends up indicating that it is Labour who are creating this opposition (i.e. if you’re black, you’re not British). This audacious implicature turned the accepted wisdom of the time (that it was the Tories who were racist and Labour who were not) on its head, and it was probably for that reason that the advertisement caused such a stir. It was also too subtle for a poster campaign, and as we see in Phillip’s passage, is often wrongly interpreted as the Conservatives’ own attempt at excluding black people from Britishness.

Although this was a fascinating one-off example, I was interested to see whether similar contextually created opposites occurred more widely and in other kinds of text. I therefore began to explore a text type as different as possible from news reporting; namely contemporary poetry. Since contemporary poetry is superficially very different in many ways from advertising slogans or political rhetoric, this was also a way of estimating the extent of this phenomenon in English texts more generally. I very quickly found examples in a number of poems I already knew quite well and in styles as different as Philip Larkin and E. E. Cummings. For example, Larkin builds one of his early love poems (from The North Ship 1945) on a number of opposites. Here is the first stanza:

Is it for now or for always

The world hangs on a stalk?

Is it a trick or a trysting place

The woods we have found to walk?

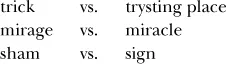

I have explored this poem in more detail elsewhere (Jeffries 1993:95), but it will serve here as a contrast to the political poster analysed above to illustrate how similar structural/semantic features of text are used by very different texts and with different effects. Stylistics is sometimes accused of ‘reading off’ meanings from structural and semantic features of texts, most famously in Fish (1981:75), but Simpson (1993:113) argues against this charge of interpretative positivism that there is no automatic assumption about the meaning of a textual feature and he demonstrates this by the use of the same analysis of two stylistically comparable examples to create two rather different interpretative effects. In the case of constructed opposites, the mechanism for creating the opposition may be the same, but the contextual meaning is different. In his poem Larkin sets up our expectations of opposition by using apparently straightforward opposites now and always, linked by the conjunction or, in the first line. We are then led by the recurrent parallel structure Is it ___ or ___? to set up further sets of new oppositions in line with the conventional one:

These oppositions are not conventional in the sense defined above, but their construction as opposites in this context is made more prominent by the alliteration between each pair as well as the shared semantic features of the paradigms with trick, mirage and sham on the one hand sharing features of deception and unreality whereas trysting place, miracle and sign on the other hand share semantic features of reality and yet a reality that seems incredible. So, incorporated into this semantic scaffolding, we have Larkin’s initial view of love: it is either just a temporary aberration (now) with no basis in reality or it is real and everlasting but wonderful (always). At the end of the poem Larkin then plays a trick on the reader when he turns the whole structure on its head, acknowledging that the original opposition on which the meaning appeared to be built is faulty, since now and always are not in fact opposed at all:

I take you for now and for always,

For always is always now.

The reader may thus (re-)discover along with Larkin that in addition to always, another, rather different opposite of now is never, while always may be seen as simply a series of moments like now (always now). The whole anxiety about whether a new love is going to last is therefore shown to be misplaced.

What appeared to be common about these two rather disparate examples from politics and poetry respectively was that they drew on the reader’s understanding about some kind of relatively stable semantic relationship between lexemes in English (i.e. opposition) and yet they were contextually creating a similar, though not conventional, opposite between other lexemes with a result that is meaningful in that particular context.

The main aims of this book are to establish some of the parameters of the phenomenon I am calling constructed opposition, using a series of case studies as the focus for answering a number of research questions as follows:

• What is the extent of created opposition across text-types?

• What are the triggers for unconventional opposites?

• What is the relevance to unconventional opposition, if any, of the semantic sub-divisions of antonymy?

• What is the function or meaning of created opposition in particular contexts?

• What insights can we obtain into the process of interpreting unconventional opposition?

Before I discuss a range of detailed examples from the data I have been analysing for created opposition, I will try to frame this study within the context of an understanding of opposition more generally. Some of these sections are inevitably short and cannot do justice to the wealth of thought and research on this topic, but I hope that it will give a sense of how this study may fit into the wider picture.

1.2 Opposition: a history of ideas

This book is about language, and about the contextual use of language in particular. However, it is clear that the notion of two words being opposed to each other semantically in the way that is implied by the term ‘opposite’ or ‘antonym’ seems to have a special status in human thought and history. Clearly, many of the most important historical events – usually wars – and most of the world’s great religions are based on some kind of conceptual binary.

This section will not be able to trace the whole history of the significance of opposites in human thought and civilization (that is another book) but it will contextualize to some extent the remainder of this study, by demonstrating that there are interesting links between the study of language usage and both psychology and philosophy in relation to concepts of opposition.

Before embarking upon the investigation of linguistic opposition-construction, it is worth pausing to reflect that opposition has been significant to philosophers since pre-Socratic times and has continued to exercise the minds of cultural thinkers since, including Plato (see Cooper and Hutchinson 1997) and Aristotle (see Ackrill 1975), followed by Hegel (1874) as well as in recent years theorists such as Derrida (1967). The nature of the human body (two eyes, ears, legs, arms etc.) has often been claimed to be the source of some of the human ideas of beauty (e.g. Plato and Aristotle) since they claimed that beauty was predicated on some principles including symmetry, which presumes the base two. One might further argue that as well as beauty, other ideas of order (and disorder) may be binary in their most fundamental manifestations. Plato’s discussion of opposites in relation to his ‘eternal forms’ confirms that for him opposites preexist our ability to perceive them, though not all forms have an opposite; thus the property of bed-ness is not opposed by a property of not-bed-ness. Aristotle, by contrast, thought that opposite qualities, such as height, were the result of experience, and that we perceived different heights first and categorized them as opposite (taller-shorter) on the basis of such perceived differences.

It is clear in any case that the existence of opposites has underpinned much of early Greek philosophy, including thinkers before Plato and Aristotle, and informed the development of certain aspects of logic and rhetoric as Lloyd (1966) points out:

And if Aristotle explicitly investigated the logic of the use of opposites, he also threw some light on the psychology of certain argumentative devices based on opposites which are similar to those we find used in earlier Greek writers. Indeed we saw that in the context of ‘rhetorical’ arguments he expressly recommends the juxtaposition of contraries as a means of securing admissions from an unwary opponent. (170)

I will return to this persuasive use of opposites in a later chapter, but here I want to note the essential nature of opposites which was tacitly assumed in this period, and saw early Greek thinkers basing much of their work on opposites:

A large number of theories and explanations which were put forward in early Greek speculative thought may be said to belong to one or other of two simple logical types: the characteristic of the first type is that objects are classified or explained by being related to one or other of a pair of opposite principles. (Lloyd 1966:7)

Though Plato developed ideas about when opposite terms may be applied to subjects, he did not distinguish between the different logical properties of some opposite pairs. Aristotle, by contrast, did make such distinctions, as well as discussing the contextual effect and power of opposite pairs. In discussing the examples of created opposition I found in my data, one of the questions that frequently occurs is whether there is a default type of opposite, the mutually exclusive and exhaustive type (‘complementaries’ in linguistics) which is assumed in the absence of active information to the contrary. We will return to this quest...