![]()

Part One

Coleridge, Romanticism and Oriental Cultures

1

‘Bid him bow down to that which is above him’: The ‘kowtow controversy’ and Representations of Asian Ceremonials in Romantic Literature

Peter J. Kitson

This chapter will discuss the nineteenth-century British fascination with the Qing ritual of the ketou, variously anglicized as ‘ko-tou’ or ‘kowtow’, as represented in a number of key Romantic-period texts. James L. Hevia has convincingly argued that the Qing demand that foreign ambassadors to the imperial court perform the full imperial kowtow of the three kneelings and the nine knockings of the forehead came to be seen as metonymic of European relations with China in the nineteenth century and quite out of step with accepted norms of the sovereignty and equality of nations, derived from the Westphalian system, established in 1634 as a consequence of the bloody Thirty Years’ War between European nation states (Hevia, 2009, pp. 212–34). Famously, the sixth President of the United Sates, John Quincy Adams, argued that the cause of the Anglo-Chinese War of 1839–42 was not opium which was ‘a mere incident to the dispute’, but ‘the kowtow – the arrogant and insupportable pretensions of China that she will hold commercial intercourse with the rest of mankind not upon terms of equal reciprocity, but upon the insulting and degrading forms of the relations between lord and vassal’ (quoted Gelber, 2007, p. 188). Yet as Hevia argues, ‘Britain went to war with China over diplomatic and commercial issues and the ketou became a kind of fetish object around which the great divide between China and the West, between archaic and modern civilizations, came to be represented’ (2009, p. 220). It was not only Europeans who objected to the ceremony: derided by Chinese intellectuals of the May Fourth and New Culture movements, the kowtow has become the key symbol of Asian despotism and remains a familiar jibe in contemporary popular speech.

Yet the issue of the kowtow was never that simple, indeed the emperor would regularly and reverentially perform the full kowtow in person to the tablets of the non-divine Confucius. In a Confucian system where the harmony of body and mind was stressed, the act expressed in bodily practice the mental veneration of the participant for the subject, in this case the emperor. Kowtowing remains a part of Buddhist, Daoist and Confucian ceremonies. Europeans who view the ceremony as indicative of a lost, archaic, ritualistic and pre-modern polity as represented in, say, Bernardo Bertolucci’s magnificent The Last Emperor (1987), will also view with equanimity the sight of the Austrian mountaineer Heinrich Harrer (played by the American actor Brad Pitt) and many others fervently kowtowing to the Dalai Lama in Seven Years in Tibet (1997). The kowtow was, and still is, a pan-Asian practice not confined to imperial China. This chapter is not concerned with the history of the ceremony in Ming and Qing guest ritual, or the formal paraphernalia of the Chinese tributary system, which has been extensively discussed elsewhere, but, rather, with the British discourse and rhetoric of the kowtow and Asian ceremonials of prostration in general. The kowtow, like infanticide, the sati, the lingchi or cannibalism, became a scandal in nineteenth-century British discourse, a marker of barbarism indicating a lack of civilization.

Ambassadors and emperors

In a series of publications Hevia has argued that Europeans and Americans fetishized the kowtow placing the ceremonial in the context of a European discourse of humiliation and abasement familiar to them but entirely foreign to Chinese understandings: ‘after Said, it is difficult to reduce complex indigenous practices to the essences required for producing the classic binary oppositions of Orientalism’ (2009, p. 213). He details the complexity of the ceremony and its multiple meanings within a Confucian cosmology that did not expound the virtues of abject servitude, far from it. The kowtow was only one facet of the complex but routine ceremony of government. Europeans chose to read into the practice their own binaries of freedom and despotism, and servitude and independence. The origin of the debate lies in the European encounters with China from the sixteenth century onwards. Ming and Qing China arranged the visits of European embassies in terms of their established system of tributary relations. Europeans with a different set of notions of international diplomacy, established by the Westphalian system were aware of Chinese practices and viewed the kowtow as a ceremony implying submission to the Chinese emperor rather than the sovereign equality that they were seeking to establish. Both forms of practice, as Hevia and David L. Porter have argued, were equally a product of the national and specific political and ceremonial discourses of their respective polities.

The first British embassy to China of 1792–4, led by the highly experienced and urbane diplomat, George Viscount Macartney, was aware of and sensitive, to an extent, to the issue of the kowtow, and the imperial court were also understanding, to an extent, of British sensibilities. The full kowtow was dispensed with, after a period of prolonged negotiation, for the Macartney audience with the emperor at the Mountain Resort for Escaping Summer Heat (Bishu shanjuang) at Chengde of September 1793. Macartney formally negotiated a compromise by which he knelt on one knee before the emperor as he would before his sovereign George III, and bowed his head, delivering his letter from the king directly into the emperor’s hands. Significantly, Macartney had not rejected the ceremony out of hand, but had agreed to perform the full public kowtow if a Chinese official of equivalent rank agreed to perform the ceremony before a portrait of the British king, or if the emperor undertook to promise in writing that on a future occasion such an official if presented to the king would also perform the full ceremony. As Hevia has shown, rather than the Qing court insisting on an inflexible ceremony, it was willing, albeit reluctantly, to allow an altered version of the ceremony to take place both to accommodate British concerns and successfully (in Chinese terms) complete the visit. This was because it understood that the visit of a British embassy was unprecedented and needed bespoke handling (Hevia, 2009, p. 227). Macartney’s resistance to undertaking the full imperial kowtow then had nothing to do with the apparent ‘failure’ that the embassy was later charged with; indeed, Macartney and others always insisted that his embassy was very much a success in the larger sense.

It was from the 15 or so accounts of the Macartney embassy that the British discourse of the kowtow and resistance to it emerged into British culture. In his Journal of the embassy, published by John Barrow in 1807, Macartney presents his refusal to kowtow as a success and an instance of the benefits of British firmness and rectitude. His act is gendered as masculine and characterized as essentially British at a time when, as Linda Colley has influentially argued, Britons were forging their own national identity, against those of other imagined communities (Colley, 1994). Macartney’s Journal provides a detailed account of how the subject of the kowtow was carefully broached, promoted and, finally, altered for the British. Macartney comments on the introduction of the kowtow issues, ‘the subject of the Court ceremonies’ by the Chinese on 15 August. He argues that ‘whatever ceremonies were usual for the Chinese to perform, the Emperor would prefer my paying him the same obeisance which I did to my own Sovereign.’ Macartney stresses his ‘first duty’ as to ‘do what might be agreeable to my own King’ whose ‘dignity . . . must be the measure of my conduct’ (1962, pp. 84, 85, 100). On 10 September, Macartney records that the Chinese agreed to ‘adopt the English ceremony’ being willing to ‘kneel upon one knee only on those occasions when it was usual for the Chinese to prostrate themselves’ (1962, p. 119). Macartney is here keen to differentiate between kneeling on one knee and bowing, which he perceives to be a manly form of ceremonial, and kneeling on two knees which he describes as a foreign act of ‘prostration’, unacceptable to a British subject of His Majesty.

Given the subsequent history of the kowtow controversy, Macartney’s Journal is very restrained and, while he notices how his Chinese minders are anxious and determined about the ceremony, he does not overemphasize its significance for him, putting it down as ‘a curious negotiation’ which provided him with ‘a tolerable insight into the character of this Court, and that political address upon which they so value themselves’ (1962, p. 119). He records that at the presentation he paid his compliments by ‘kneeling on one knee, whilst all the Chinese made their usual prostrations’, remarking that the impression given to him of the entire ceremony was ‘that of calm dignity, that sober pomp of Asiatic greatness, which European refinements have not yet attained’ (Macartney, 1962, pp. 122, 124). Macartney shows how the Qing court is flexible, arguing that the allegedly ‘immutable laws’ of the Chinese as instanced in ‘the ceremony in my own case’ are abrogated when necessary. He argues that such ‘ceremonies of demeanour’ are merely a ‘trick of behaviour’ and that once they have been thrown off, the Chinese are easy and familiar, engaging in free conversation as they are ‘naturally, lively, loquacious and good-humoured’ (Macartney, 1962, pp. 153–4, 222–3). Macartney shows no serious understanding of the semiotics of Qing guest ritual, but neither does he dismiss the Chinese as rigid, inflexible and antiquated.

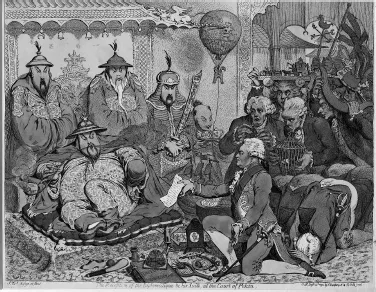

The emergence of the kowtow as a symbol of Asiatic alterity for Britons, however, begins to emerge more strongly in the other published accounts of the embassy. In 1792, James Gillray imaginatively depicted the reception of Macartney’s embassy at the Qing empire as one of submission before a heavily orientalized and unpleasantly racialized depiction of the imperial court in his print, The Reception of the Diplomatique & His Suite at the Court of Pekin (Figure 1.1).

Macartney kneels on one knee but the remainder of the embassy prostrate themselves absurdly in front of an unrecognizable version of the Qianlong emperor, promoting the very worst stereotypes of European orientalist imaginings. Gillray’s looking ahead to Macartney’s forthcoming participation in the ceremonial of the Chinese court clearly reads the event as an example of Chinese despotism and British folly, with the emperor requiring backhanded payments and the British bringing mere toys and ephemera in response. At the same time, Macartney’s refusal to kowtow indicates his unwillingness to participate in the tawdry ceremonial: a potent and prophetic iconography of the new British imaginings of the Asian ritual.

Of course, Gillray was only positioning China within the much larger discourse of oriental despotism and prostration as applied to British politics. The discourse of the kowtow with its refusals, negotiations and compromises, was frequently played out in generalized oriental settings, Ottoman, Persian and Javan as this chapter will argue. Later George Cruikshank would present the reception of Lord Amherst to the Prince Regent at the Royal Pavilion, Brighton prior to his embassy’s embarkation for China in 1816 in very similar terms, in The Court at Brighton a la Chinese!! (1816). Here a corrupt and despotic Regent, hungry for expensive and exotic chinoiserie items requests Amherst to ‘get fresh patterns of Chinese deformities to finish the decoration of the Pavilion’ in return for bottles of claret, pornographic prints and novels, and portraits of the Regent. Here it is the royal family and ministers who are dressed as mandarins.

Figure 1.1 James Gillray (1792), The Reception of the Diplomatique & His Suite at the Court of Pekin. London: H. Humphrey. © Trustees of the British Museum.

In the public account of the embassy, officially authored by George Leonard Staunton, we can see the development of the kowtow into a more redolent symbol of China, than which it is ‘difficult to imagine an exterior mark of more profound humility and submission, or which implies a more intimate consciousness of the omnipotence of that being towards whom it is made’. The Account argues that the Chinese, despite the evidence of the embassy, are unable to discriminate between their obligations to the person of the emperor and those ‘of other nations or individuals . . . which are unbounded’. The Account details Macartney’s negotiations, imputing to him an awareness ‘of the tenaciousness of the Chinese court in exacting ceremonies, in which the humiliation on the one part, contributed, perhaps to render the embassies so grateful to the other’ (Staunton, 1797, vol. 2, pp. 129–30). The Account argues that, as the Chinese did not know the English well, then any ‘sacrifice of dignity’ would fail to impress them with their true character. Hence, Macartney determines on a ‘well-judged, courteous, but not abject, conduct’ with which to impress the Chinese in the face of the ‘unconditional compliance demanded by the Legate’ (Staunton, 1797, vol. 2, pp. 130–7).

Similarly, the account of the comptroller of the embassy – John Barrow’s rather self-serving Travels in China of 1804 – presents the kowtow as a symbol of both Chinese intransigence and China’s lack of progress. Barrow feels he must defend his erstwhile employer from the charge that his refusal to adopt an ‘unconditional compliance with all the humiliating ceremonies which the Chinese might have thought proper to extract from him’ would have led to a more favourable conclusion to the embassy (1804, p. 7). He argues that the willingness of the next European embassy, that of the Dutch led by van Braam in 1794–5, to ‘humiliate themselves at least thirty different times’ had led to no positive outcomes. Barrow questions what ‘advantages can reasonably be expected to accrue from a servile and unconditional compliance with the submissions required by this haughty government’ after ‘such a vile reception and degrading treatment’. Indeed Barrow recalls how van Braam, a corpulent man, was subject to the laughter of the imperial court when his wig fell off in front of the emperor while undertaking the ceremonial (1804, pp. 10, 11, 13). Barrow argues that the Chinese treated the English with more respect than the Dutch because of ‘the character and independent spirit’ of the nation as well as its great power over which they cast ‘a jealous eye’. It was Macartney’s ‘manly and open conduct’, which affirmed this and his refusal to kowtow. Barrow writes of the profound effect of ‘the refusal of an individual to comply with the ceremonies of the country’ on the emperor and his court and how ‘greatly must their pride have been mortified’ (1804, pp. 17–18). In Barrow’s account the Qing court is presented as proud, haughty and insolent, never for a moment relaxing its rigid ‘long established customs’ except in the single case of the British. The lesson learnt by the Macartney embassy is clear, ‘a tone of submission, and a tame and passive obedience to the degrading demands of this haughty court, serve only to feed its pride, and add to the absurd notions of its own vast importance’ (Barrow, 1804, pp. 20–1, 24). In his review of Barrow’s Travels for the Annual Review of 1805, Robert Southey also explicitly locates the ‘failure’ of the embassy as stemming from the fact that ‘Lord Macartney had refused to perform the nine prostrations before the emperor’ (1805, p. 73).

Barrow’s advice for dealing with Asiatic powers had become a virtual gospel by the time of the second British Embassy to China of Lord Amherst in 1816–17. By this time, relations between the two empires were becoming increasingly fraught as the balance of both trade and power shifted in favour of Britain and exports of Indian opium flooded the Chinese market in an attempt to replace silver as a means of paying for the huge volume of Chinese tea exports to Britain. Yet even in 1816, there is evidence that the Jiaqing emperor was willing to adapt the ceremony of the kowtow in an analogous manner to that practised by Macartney (Pritchard, 1943, pp. 173–4). Amherst’s instructions also directed him to conform ‘to all the ceremonies of that court’ which did not lessen his dignity or ‘commit the honour of your Sovereign’ (Staunton, 1824, p. xx). The diplomat, Sir Henry Ellis, while admitting the ceremony to be repugnant and signifying ‘oriental barbarism’ believed that it was a point of ‘etiquette’ that might have been complied with rather than sacrifice the entire objects of the embassy (1817, p. 151). Amherst also proposed to repeat his kneeling and bow...