![]()

1

Introduction

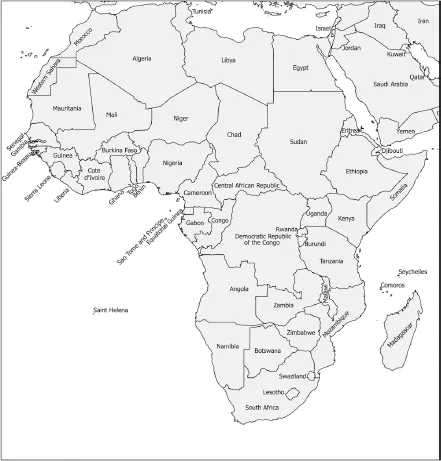

This short volume is intended to bring to the attention of the wider archaeological community the potential for the investigation of Africa’s more recent past. Less broadly than this it represents a call for consideration to be paid to some of East Africa’s neglected nineteenth-century urban heritage. It necessarily concentrates upon Tanzania and Kenya, as the towns within these states form not only the bulk of my research experience, but also the key entry points into Africa for many of the nineteenth-century colonial regimes which were to shape the destinies of the people of the continent. These towns include Mombasa (Kenya), Tanga, Pangani, Bagamoyo, Dar es Salaam, Kilwa Kivinje, Chole (United Republic of Tanzania) and Zanzibar (a semi-autonomous part of Tanzania under the Revolutionary Government of Zanzibar). The work looks at the remains of the physical impact of European interaction with the people and environments of nineteenth-century East Africa and compares these with examples of colonial approaches outside what was the British and German sphere of influence. It does this through the examination of European-built heritage and the ways European powers manipulated space within towns in order to control people and economies. It also looks at the importance of conserving this heritage as a tangible reminder of the impact nineteenth-century colonialism had on forming our contemporary opinion of, and life in, Africa (Figure 1).

Within this broad theme there are a number of interconnected aims. The main aim is to examine the role of the built environment as a tool of ideological expression within the colonial environment, and to look at how it may be possible to begin to decipher the intentions and impacts of Europeans in nineteenth-century East Africa from the structures they created. Secondly, I hope to demonstrate the possible ways in which archaeology can be used to address fundamental questions of social and political change in colonial regimes. In other words, how do the physical remains express the social impact that colonial activity had on people in the nineteenth century?

The impact of nineteenth-century European colonialism upon world cultures has been, and continues to be, undeniably profound. More and more in contemporary archaeology (and heritage studies), this impact is being recognized in the way we formulate our perception of the past. Whether we look at pre-colonial societies or colonial and post-colonial heritages it is all unavoidably (it can be argued) viewed through the lens of the European colonial influence. This recognition raises some interesting questions about the theoretical validity of a piece of work such as this one. As a piece of work which is in essence a study of European colonial activity from an unavoidably European perspective, the remainder of this first chapter is therefore intended to give an indication of the kinds of theoretical questions that underpin the ideas expressed throughout the rest of the book.

Theoretical foundationsa

European activity in nineteenth-century East Africa falls within the broad historical phase of Second Modernity. The term Second Modernity is a theory first developed by philosopher Enrique Dussel in relation to the historic period between the seventeenth century and the second half of the twentieth century (Rhodes 2013). It refers to the idea that people who live under colonial rule are subject not only to Western economic and political forces but are also influenced in the way they see and think of themselves (and others) based upon a change in mindset brought about by Western influence and control. The Second Phase of European Colonialism is the period of world history when global mercantile activities led to the development of European colonies, most notably by Britain, Holland, France and later Germany, and largely focused on Africa and India from the seventeenth century until colonial states began to acquire independence in the second half of the twentieth century. This is sometimes referred to as New Imperialism and follows the earlier period of European colonialism (or First Modernity) that saw Spanish and Portuguese exploitation in the Americas. The global historical activity that occurred during the Second Phase of European Colonialism resulted in the development of subaltern non-colonialist social theory such as Second Modernity. Developed out of post-colonial studies and specifically Latin American Social Theory, the idea of Second Modernity was a response to Marx’s lack of analyses of class struggle in Latin America and his apparent scepticism in the development of the bourgeoisie in non-European societies. The bourgeoisie were central to Marx’s theory of social change, or ‘Universal History’, as it was the bourgeoisie who represented the first revolutionary class in history and who (through maintaining the ability to control and revolutionize the means of material production), were able for the first time to actively influence and change social relations. This, however, he did not apply to feudal societies. It was the development of international markets through the tool of colonialism that Marx saw as the necessary stage through which a previously feudal society must pass before the creation of the revolutionary bourgeoisie. His assessment was, however, from a purely European perspective and lacked investigation into the development of capitalism outside that of the European model (i.e. where colonial control implanted European structures into non-European geographies). As Castro-Gómez (2008: 262) observes: ‘Latin America was, it seemed to Marx, a grouping of semi-feudal societies governed by large landowners that wielded their despotic power without any organized structure.’ Colonialism is then, for Marx, a tool of capitalism and responsible for the overthrow of feudal societies in the march toward revolution. Colonialism in effect ‘delivers’ capitalism, and by association the revolutionary bourgeoisie. He did not see, as others have subsequently done, that colonialism is more than an economic or political phenomenon. And it was the study of this more expansive and socially pervasive impact of colonialism that led to the growth of late twentieth-century subaltern social theories from former European colonies of which Second Modernity and the writing of the Argentinean Enrique Dussel was one.

Dussel argues that European modernity was founded on materiality that had been specifically created after Spain’s sixteenth-century territorial expansion (Castro-Gómez 2008: 272). He goes on to argue for the historical existence of two modernities. The first, beginning in the sixteenth century when the Christian Renaissance spread globally via Spain’s colonial domination of the Americas, and the second, was the colonial expansion into Africa and Asia by Britain, Holland, France and later Germany. The impetus for Dussel’s thinking was an attempt to dismantle the Eurocentrism of modern philosophy believing that modern philosophy was another representation of European conquest over the rest of the world. In this way mirroring Said’s ideas of ‘Europe’ and the ‘Other’ (Said 1979) and Wallerstein’s (1980) world-system with its ‘Core’ and ‘Periphery’. In doing this Dussel aimed to liberate non-European social discourse from the ‘Eurocentric myth of modernity’ (1995: 148).

Another important figure in the development of the idea of Second Modernity and its intrinsic tie to colonialism is Walter Mignolo. Mignolo developed a critique of Wallerstein’s world-systems theory based upon Dussel’s ideas of the (non-bourgeois) Hispanic world, arguing that ‘World-systems analyses is indeed a critique of Eurocentrism, but a Eurocentric critique of Eurocentrism’ (Mignolo 2000: 314). World-systems analyses are based upon a neo-Marxist model of economic history formulated primarily by Wallerstein in the 1970s and 1980s (Wallerstein 1980, 2005). It attempts to explain economic globalization, or supra-national economic activity, through the concept of inequitable interrelation between national economic units. The model’s primary supposition being that the economies of ‘the developing world’ are in every way effecet by (and should therefore be analysed in terms of their relation to) the economies of the wider world. A world which is dominated by the USA, Japan and Europe. Like Marx, Wallerstein argues that the modern capitalist world-system originated in Europe in the sixteenth century via the economic transformation from feudal organization to capitalist. Mignolo bases his criticism of Wallerstein’s world system on the opinion that the theory is simply another example of Western ideas being presented to non-European peoples as the model for critical analyses. In his explanation Mignolo quotes Darcy Ribeiro:

In the same way that Europe carried a variety of techniques and inventions to the people included in its network of domination …it also introduced to them its equipment of concepts, preconcepts, and idiosyncrasy that referred at the same time to Europe itself and to the colonial people. The colonial people, deprived of their riches and of the fruit of their labour under colonial regimes, suffered, furthermore, the degradation of assuming as their proper image that was no more than the reflection of the European vision of the world … . (Ribeiro 1968 in Mignolo 2000: 13)

In looking at cultural identity and modernity in Latin America, the Peruvian sociologist Aníbal Quijano also put forward the argument during the 1990s that colonial power cannot be reduced to economic, political and military domination of the world by Europe, but that it also supports and spreads globally European models of the formation of knowledge in modernity (Castro-Gómez 2008: 280). This is what Gómez calls the ‘coloniality of power’ and sees the action of colonization as attempting to replace indigenous forms of knowledge with those more appropriate to the underlying aims of the controlling Western regime. I hope to demonstrate through this book how these forms of colonial power and their attempts to control indigenous activity are visible through the building history of colonial Africa and how archaeology can be used as a technique of analyses.

Identities

Central to this strand of social theory and post-colonial studies is the question of subjectivity. Accordingly there is a long tradition of intellectuals addressing this question. Among them Dussel, Rodolfo Kusch – whose Philosophy of Indigenous Thinking as Equal to European Thought was published in 1970 but not translated into English until 2010 – and earlier still the ‘cannibal’ movement in early twentieth-century Brazil and the ‘Forja’ movement in Argentina in the 1930s. During the 1990s, subjectivity and the ways in which people describe themselves to others also became a significant area of interest within archaeology and cultural studies (see for example Hall 1996; Gosden 1999). The primary questions were related to identity, i.e. the process and manner in which individuals, groups, communities, cultures and institutions define themselves. However, the debate as to the nature of the establishment of identity can be approached in two ways. Firstly, one can argue for fixed categories based upon definable ‘foundational’ differences. Secondly, one can view one’s perception of identity as a more fluid phenomenon based upon reaction/reflexivity and dialogue (both inner and outer) (Meskell and Preucel 2004). This first taxonomical approach can be useful when it becomes necessary to quantify groups of individuals, but can stray into dangerous labels/pigeonholes and meta-identities. The second, more post-structural view, approaches the formation of identity as involving the negotiation of ‘race’, class, religion, sexuality, ethnicity and gender, as well as the environmental and cultural context in which individuals find themselves. Constructivists would even go so far as to argue that identities do not exist but are in reality discursive constructs which are formulated through one’s personal dialogue with one’s socio-cultural, physical and political environment. It is the nature of this dialogue and one’s autonomy within it that has developed into a philosophical debate as to the role of the self in the formation of identity. In the past the two main protagonists within this debate were Foucault (1972) and Giddens (1991). Both agreed that:

… self-identity is negotiated through linked processes of self-exploration and the development of intimacy with the other. (Giddens 1991: 97)

However, the debate rests upon the level of autonomy available to the individual within the multiple and competing discourses within the post-colonial/colonialist world. Foucault (1972) argues that the individual is subservient to the dominant social discourse, which is based upon the power of shared knowledge. Alternatively, Giddens (1991) views the individual within society as less the passive participant and more the creative transformer:

The self is not a passive entity, determined by external influences; in forging their self-identities, no matter how local their specific contexts of action, individuals contribute to and directly promote social influences that are global in their consequences and implications. (Giddens 1991: 2)

Giddens’ structuration theory (1991) gives the individual an understanding of the social context in which they exist and allows for reaction against it. This not only allows for one to develop multiple situationist identities but also allows for the idea that individuals have an indelible political and social autonomy. This is a concept central to the post-colonial debate on the role of participants in colonial activity. Furthermore, the search for identity, be it individual or society, requires a meta-narrative in order to formulate a dialogue between life experience (meta-narrative) and perception (the self). This meta-narrative takes the form of culture whilst cultural identity is the extent to which one is representative of a given culture behaviourally, communicatively, psychologically and sociologically.

All of these theoretical strands exist within the history of the development of post-colonial African identities, or more specifically, the international politicization of identities in the twentieth-century. As Hall (1990) demonstrates in an essay addressing the African diaspora, wrestling control of contextualizing meta-narratives is central to the struggle for equality:

Not only, in Said’s ‘Orientalist’ sense, were we constructed as different and other within the categories of knowledge of the West by those regimes. They had the power to make us see and experience ourselves as ‘other’. Every regime of representation is a regime of power formed, as Foucault reminds us, by the fatal couplet, ‘power/knowledge’. (Hall 1990: 225)

As a Western colonial science, archaeology has played a large historical role in Europe’s conquest of people and places with its inception in antiquarian exploration and acquisition. But as Hall demonstrates, archaeologists have begun to embrace deconstructive philosophies and look more deeply to the examination of alternative historical cultural narratives. One way it can be argued to have done this is through the development of Historical Archaeology. One of Historical Archaeology’s earliest proponents defined it as the study of ‘the cultural remains of literate societies that were capable of recording their own history. In this respect it contrasts directly with prehistoric archaeology, which treats all of the cultural history before the advent of writing – millions of years in duration’ (Deetz 1977: 5). More appropriately in view of the earlier discussion on the influence of Marx on contemporary thinkers’ approach to colonialism, Charles Orser suggests that historical archaeology ‘investigates complex, socially stratified societies, with people living in literate, pre-industrial, or industrial civilizations. Social stratification means that a society is divided into two or more groups that are ranked relative to one another in terms of economic, social, or other criteria.’ (Orser 2004: 240). By recognizing this stratification within the archaeological record it can be argued that alternative, non-dominant cultures can be defined and subaltern identities can be recognized.

Colonial processes

Our current understanding of colonial processes is largely based upon the development of Western anthropologists. More recent studies have begun ...