- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The ancient Mesoptamian city of Ur was a Sumerian city state which flourished as a centre of trade and civilisation between 2800–2000 BCE. However, in the recent past it suffered from the disastrous Gulf war and from neglect. It still remains a potent symbol for people of all faiths and will have an important role to play in the future.

This account of Ur's past looks at both the ancient city and its evolution over centuries, and its archaeological interpretation in more recent times. From the 19th century explorers and their identification of the site of Mukayyar as the Biblical city of Ur, the study proceeds to look in detail at the archaeologist Leonard Woolley and his key discoveries during the 1920s and 30s. Using the findings as a framework and utilising the latest evidence from environmental, historical and archaeological studies, the volume explores the site's past in chronological order from the Ubaid period in the 5th millennium to the death of Alexander. It looks in detail at the architectural remains: the sacred buildings, royal graves and also the private housing which provides a unique record of life 4000 years ago. The volume also describes the part played by Ur in the Gulf war and discusses the problems raised for archaeologists in the war's aftermath.

This account of Ur's past looks at both the ancient city and its evolution over centuries, and its archaeological interpretation in more recent times. From the 19th century explorers and their identification of the site of Mukayyar as the Biblical city of Ur, the study proceeds to look in detail at the archaeologist Leonard Woolley and his key discoveries during the 1920s and 30s. Using the findings as a framework and utilising the latest evidence from environmental, historical and archaeological studies, the volume explores the site's past in chronological order from the Ubaid period in the 5th millennium to the death of Alexander. It looks in detail at the architectural remains: the sacred buildings, royal graves and also the private housing which provides a unique record of life 4000 years ago. The volume also describes the part played by Ur in the Gulf war and discusses the problems raised for archaeologists in the war's aftermath.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Ur by Harriet Crawford in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Biblical Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Rediscovery of Ur

To many Europeans in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the name Ur of the Chaldees conjured up an image of the archetypal mysterious Orient peopled by bearded figures in long white robes or wild tribesmen on fine horses. To Iraqis today, Ur is one of the oldest and most important of their heritage sites. Thanks to many years of meticulous work by scholars, we now know that the real settlement of Ur flourished for more than 5,000 years, and, for much of that time, was an important political and economic centre. This longevity was the result of its geographical position at the head of the Persian Gulf. This gave Ur control of one of the most important early trade routes that brought metals and many other goods into the Mesopotamian heartland. Control of the metals trade in particular undoubtedly gave Ur considerable political leverage, although other, less important, land-based trade routes existed as well. In addition, the trade brought great wealth to the city – wealth which is evident in the monuments and artefacts recovered from the site.

To the north-west the Euphrates connected Ur directly to the Anatolian heartland, making it one of the most strategically placed of the early cities. Few others could boast of such excellent internal and external connections. Ur’s heyday came in the second half of the third millennium BC when its rulers competed on equal terms with the other cities of the plain and eventually imposed their rule over the whole area, creating what has been called the earliest empire in the region. After its destruction, in about 1800 BC, the city’s trading links, coupled with the standing of its divine patron, the Moon God Sin, led to a swift rebuilding and a new life as a regional capital. It was only the retreat of the Gulf coast southwards and then the migration of the course of the river eastwards that caused Ur’s abandonment.

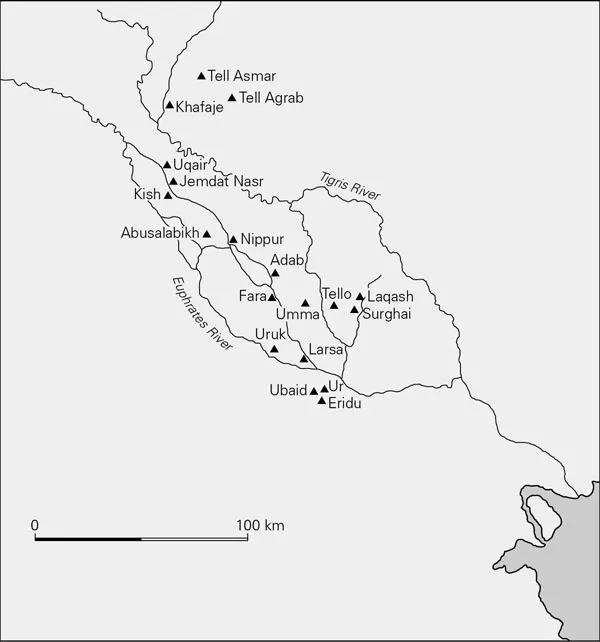

The early fame of Ur in the West was due to the description in Genesis 11.8–31, which says that the city was the birthplace of Abraham, the founding father of the Jewish people. On this timescale its identification with a group of mounds ten miles west of the Euphrates in what is now a sandy desert in southern Iraq is relatively recent (Map 1). The first European to visit the site was probably Pietro della Valle, the early seventeenth-century Italian traveller who, when he eventually returned home, brought back with him bricks with cuneiform inscriptions, which no one could read, and a number of cylinder seals. In the early nineteenth century, under the Ottoman Empire, interest revived among Europeans in identifying the exact place where the ancient city had stood. A number of candidates were proposed, of which the favourite was a tell called variously Umghyer, Mughyer, Múgeyer, or Tell el-Mukayyar, the hill of pitch/bitumen. Bitumen was used instead of mortar in some of the exposed brickwork and this gave the tell its name. The site was visited in 1835 by J. Baillie Fraser, who described the two-storey construction at the heart of the mound, later to be identified as the ziggurat, or temple tower, and paced out its dimensions.

Map of Mesopotamia

A certain amount of confusion was caused by various misidentifications, first by Sir Henry Rawlinson, the remarkable diplomat and scholar, who was one of the first to translate cuneiform. He initially proposed that Uruk/Warka was the biblical city of Ur. Later, Colonel Chesney, who was in charge of the ill-fated ‘Expedition for the survey of the rivers Euphrates and Tigris’, proposed a more elaborate idea. The expedition had set out in 1835 in two ironclad paddle steamers to navigate the length of the Euphrates from Birejik in modern Syria to the head of the Persian Gulf. The report of the expedition, which it was hoped would provide a shorter and more convenient passage to India, was not published for fifteen years because of various problems. When it did appear, Chesney claimed that the city of O’rfáh (Urfa) in Syria was the biblical Ur, perhaps because there is a strong local tradition that Abraham was born there; the cave in which this was said to have happened is still a sacred place today. He also suggested that the name then apparently migrated to Kal’ah Sherkát (close to modern Ashur), and finally came to rest in the area around Mujáyah, as he called it. ‘The mound of Mujáyah, it is presumed, marks the site of the ancient capital of Aur, the Orchoe of Ptolemy …’ A further layer of uncertainty was added by the biblical tradition which also associated the name of Abraham with Harran (Gen. 11.31), near modern Urfa.

Even after the correct identification of the site by Rawlinson as a result of his decipherment of cuneiform inscriptions on bricks brought back by W. K. Loftus after a visit there in 1849, some doubts remained. In the inscription Rawlinson also recognized the name of the god Sin, the moon god to whom the ziggurat was dedicated, and the name of an area of the city called Ibra, which he took to be the same word as Abraham. A consensus was finally reached, largely as a result of Woolley’s work, and the identification of Tell el-Mukayyar with Ur is now generally accepted.

The interest caused by this identification resulted in 1854 in the British Museum employing J. E. Taylor, the British vice-consul in Basra, to investigate various sites in southern Iraq, including Ur. Permission had to be obtained from the sultan in Constantinople for such work and many of the finds found their way to the imperial treasury there. Taylor’s Report to the Royal Asiatic Society in 1854 described the ziggurat with its buttresses and air holes in the walls. He identified two storeys and found many fragments of blue-glazed bricks and copper nails on the top of the mound, but his most important finds were four well-preserved foundation cylinders of Nabonidus of Babylon. These were buried by the king at the four corners of the ziggurat when he restored it, and he was also responsible for the blue-glazed bricks, which had probably faced the top storey. In addition, Taylor dug what he thought was a house with a narrow, arched door, but which later work showed was part of the Gate of Judgement, or E-dub-lal-mah, where justice was dispensed at one of the entrances to the inner court of Nanna. He also recognized many other mounds lying south of the ziggurat as part of the city. Sadly, after Taylor’s second season when he worked mainly at Eridu, where another ziggurat was found, the British Museum decided to concentrate their efforts and their money in Assyria, where the pickings for museums were much richer. It was as a result of this work in the north that the museum acquired its magnificent collection of Assyrian palace reliefs. Work in the south did not begin again for more than sixty years.

Looking back, we can see that these pioneering explorers achieved a good deal. They showed beyond doubt that the early civilizations of Mesopotamia had built large cities with monumental buildings in the inhospitable south as well as in the more fertile northern plains of Iraq. These men worked with no training and little equipment, in a hostile environment where water was short and sandstorms a common occurrence. It was also dangerous, as their camps could be prowled around by lions or by desert raiders, and the workforce was usually made up of local people whose attitude varied between mild curiosity and outright hostility. It was also dangerous for the tells they explored, as there was also a pervasive feeling that these strange foreigners must be looking for gold. This belief was bound to lead to theft, illicit digging and the plundering of sites.

The site of Ur itself is not welcoming. It lies 220 miles south of Baghdad and about 10 miles west of the modern course of the Euphrates in a low-lying wasteland of dunes and sand. It used to be close to the Basra to Baghdad railway, part of the proposed Berlin to Basra line that was never completed. It was possible to get off the train from Baghdad at the grandly named Ur Junction, where a branch line turned off to Nasariyah, and drive a mere two miles across the desert to the site itself, but the station was closed sometime after the Second World War, leaving a long, hot journey in a four-wheeled vehicle as the only option. It is now apparent, with the advantages provided by satellite photographs and modern boring equipment, that its surroundings were very different in the past. At the time the settlement was founded, in the Ubaid period from the late sixth to late fifth millenna BC, the level of the Persian Gulf was rising, and by the Uruk period a 1,000 years or so later, the water was 2.5 metres above today’s level with the coastline reaching as far as Ur itself, creating new marshes and a new delta. Pournelle, an expert in the interpretation of satellite photographs, describes these early settlements like Ur as ‘islands embedded in a marshy plain, situated on the borders and in the heart of vast deltaic marshlands … Their waterways served less as irrigation canals than as transport routes.’ Loftus, writing in 1857, states that even then, ‘During inundation [Ur] was completely surrounded by water’, and Mallowan in the 1920s observed the same phenomenon.

This conjures up a rather different picture from the one we see today and suggests that the economy of the early settlement here, and in other comparable locations in southern Iraq, was largely dependent on the surrounding marshes for survival. The marshes provided food, fish, birds, edible tubers and much else, as well as raw materials such as reeds, which were used for everything from roofing to boats, containers, fodder and fuel. Crops could also be sown on the tops of the levees, or turtle backs as they are called by Pournelle, and date trees cultivated, but these were initially of less economic significance. The marshes may not have been the healthiest locations, but they were extraordinarily rich in the essentials of early village – and even urban – life.

With the recent recognition of the vital importance of the marshes as a sustaining environment for these early settlers, it has to be asked if the introduction of agriculture had the transforming effect on society that is generally assumed. It could be argued that agriculture becomes less significant as a stimulant for the development of the first villages in the deltaic region and overturns many of our previous assumptions about the so-called agricultural revolution. The proposed picture of the vital importance of the marshes is supported by the earliest texts from the end of the fourth millennium. Although agriculture was well established by then, the texts still stress the importance of fish and reeds to the local economies. The settlements began to trade as a means of acquiring materials the marshes could not supply.

By the early second millennium, the waters of the Gulf began to retreat after a series of fluctuations, and the subsistence balance shifted irrevocably towards irrigation, agriculture and animal husbandry as the most important sources of essential foods. Trade continued to grow and, as we shall see, the site of Ur boasted two harbours, one on the river and one on a canal, to facilitate travel and trade. As the head of the Gulf retreated southwards, access to the important maritime route down the Persian Gulf must have become more difficult. This factor almost certainly contributed to the economic decay of the city.

Fifty years and more after Taylor left Ur, archaeological work was restarted in 1918 after the First World War, when the presence of British troops brought some security to the region. The situation was very different in other ways too. Archaeology was becoming a profession in its own right for which training and certain skills were becoming essential, rather than being seen as an addendum to exploration. R. Campbell Thompson, who was serving as an Intelligence officer on the staff of the British Army in Mesopotamia, and who had previously been an assistant at the British Museum, went to Ur to undertake some experimental work for the museum. The results were sufficiently interesting for Dr Hall, also a wartime Intelligence officer, to be deputed to go to Ur the following year to carry out further excavations. Hall had started work at the British Museum in 1896 as an assistant to E. A. Wallis Budge, becoming Assistant Keeper, Department of Egyptian and Assyrian Antiquities, in 1919. He had extensive experience of digging in Egypt, as well as a good knowledge of the objects in the museum’s collections, making him well equipped to dig at Ur.

Hall was given seventy Turkish prisoners of war, together with their Indian guards, to work for him. This detachment of soldiers was in addition to the local workers supplied by their sheikh. Hall needed to find ways to control a large and unskilled workforce with only the help of three NCOs (non-commissioned officers), none of whom had any archaeological experience. He achieved a remarkable amount in a season lasting about three months, especially when it is remembered that he also worked – though for much shorter periods – at Eridu and al Ubaid, where he uncovered some of the superb decorations fallen from the façade of a mid-third-millennium temple. At Ur, he uncovered the building, later to be identified as a possible palace, the E-Hur-sag, built within the sacred precinct that surrounded the ziggurat. He also traced the south-east face of the ziggurat itself. In addition, he retrieved numerous tablets and other small finds, and dug a number of graves, including some dating back to the late third millennium.

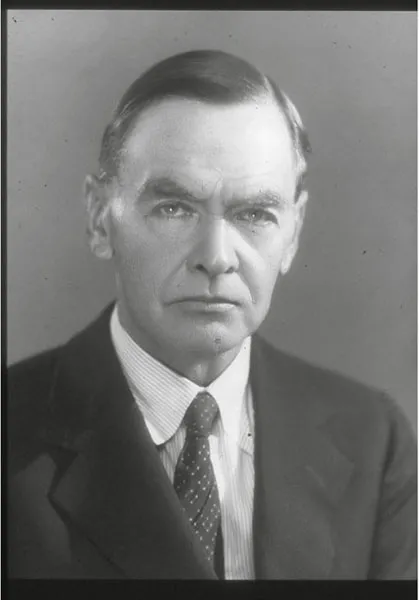

Hall’s work was limited to a single season because the British Museum had no money to pay for further work – a frustrating situation familiar to many archaeologists since. In 1922, however, George Byron Gordon, the Director of the University Museum in Philadelphia, who knew of Hall’s work, proposed that a joint expedition with the British Museum should be set up to work at Ur, and that Leonard Woolley, whom he knew already (see page 8), should be appointed to lead the expedition (Fig. 1.i). Woolley was to work at Ur for the next twelve years.

1.i Portrait of Sir Leonard Woolley © National Portrait Gallery, London

Charles Leonard Woolley was a clergyman’s son, born in 1880. He went up as a scholarship boy to New College Oxford, intending to go into the church himself. However, he did less well academically than expected, and reluctantly gave up the idea of the ministry. He had no clear idea of what he would do instead, although he toyed with the idea of teaching. He describes how he became an archaeologist in the following paragraph:

I have seldom been more surprised in my life than I was when the Warden of New College told me that he had decided I should be an archaeologist … I must confess that when the prospect did present itself, not as a mere idea to be played with (for one did not lightly play with the Warden’s decisions), but as something definite and settled, I was not altogether happy about it. I preferred the open air and was more interested in my fellow men than in dead-and-gone things.

As it turned out, the Warden had made an inspired decision.

Woolley began his archaeological career in 1905 as an assistant keeper in the Ashmolean Museum and had his first taste of fieldwork on Hadrian’s Wall. In his second season in the area, he found the so-called Lion of Corbridge, proving that he already had that most important of archaeological assets: luck. However, three years later he left the Ashmolean and went to work for the University of Pennsylvania in the Nubian Desert. Here he was introduced to the Near East, to Arabic, and to the meticulous methods of excavation and recording used by Randall MacIver, who had been taught by Flinders Petrie himself. Later, Woolley was to use a version of Petrie’s famous sequence-dating when excavating at Ur. The method had evolved when Petrie was digging a huge cemetery whose date was unknown. Petrie recorded the relative depth of each grave and of the pots found in them, arguing that those at the bottom of the sequence had to be the oldest. In this way he was able to build up a picture of which pots belonged where in the sequence and to use that relative dating to tie his cemetery to other better-dated sites where possible. This work in Nubia was also the beginning of an important partnership between Woolley and Pennsylvania that was cemented by a visit there in 1910.

Woolley’s career progressed rapidly and, in 1912, he was appointed to lead a field expedition to Carchemish, under the aegis of the British Museum. He was accompanied by T. E. Lawrence as his assistant and they became great friends. Even more impo...

Table of contents

- Archaeological Histories

- Title

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- 1 The Rediscovery of Ur

- 2 The Earliest Levels at Ur

- 3 Uruk and Jemdat Nasr Phases

- 4 The Rise of the City State

- 5 Art and Technology: Objects from the Royal Cemetery

- 6 The Defeat of the City State of Ur by the Rulers of Akkad

- 7 Imperial Ur: The Public Face

- 8 Ur Beyond the Sacred Precinct: Ur III to Isin-Larsa (Early Old Babylonian) Periods

- 9 Post-imperial Ur: Kassites to Neo-Babylonians

- 10 Death and Afterlife

- Timelines

- Further Reading

- Index

- Copyright