![]()

1

Ottoman Sarajevo

In the summer of 1875, Arthur Evans, later to find fame and knighthood as the excavator of the Minoan civilization, was on a walking tour of Bosnia-Hercegovina during the troubled period of the ‘insurrection’ – revolts by peasants against Ottoman rule in Bosnia-Hercegovina.1 The country, so far relatively unexplored by Westerners, was coming increasingly under the political spotlight in Britain and elsewhere, and Evans was curious to see it for himself. He provides a valuable record of Sarajevo at the time seen through Western eyes. He describes the city as

a vast garden, from amidst whose foliage swell the domes and cupolas of mosques and baths; loftier still, rises the new Serbian cathedral; and lancing upwards, as to tourney with the sky, near a hundred minarets. The airy height to the East, sceptred with these slender spires of Islâm [sic] and turret-crowned with the Turkish fortress (raised originally by the first Vizier of Bosnia on the site of the older ‘Grad’ of Bosnian princes), commands the rest of the city, and marks the domination of the infidel. Around it clusters the upper town, populated exclusively by the ruling caste; but the bulk of the city occupies a narrow flat amidst the hills, cut in twain by the little river Miljaška [sic], and united by three stone and four wooden bridges. Around this arena, tier above tier – at first wooded hills, then rugged limestone precipices – rises a splendid amphitheatre of mountains culminating in the peak of Trebević, which frowns over 3,000 feet above the city – herself near 1,800 feet above sea level.2

Evans’ account sees the city in essentially ‘Oriental’ terms, noting the domination of Ottoman rule as expressed through the ‘sceptres’ of the minarets and the ‘crown’ of the fortress.3 The place he describes had been founded in the fifteenth century after the Ottoman invasion of the region and shared many common features with other Ottoman towns and cities in Bosnia-Hercegovina and further east, in terms of its spatial organization, its economic and commercial basis, buildings, institutions and élites. It was home to four main confessional groups with their corresponding social and cultural traditions; Serbian Orthodox, Roman Catholic and Sephardic Jews were allowed to organize their own religious and communal affairs under the Ottoman millet system, while the Muslim majority in the city held the dominant position, as reflected in Evans’ description.

The presence in Sarajevo by the 1860s of the consulates of the six major powers had expanded the number of curious westerners, both in an official capacity and those who came as tourists to explore, paint and write about this relatively unknown region. Although it was only a few days’ journey from the ‘West’, it had for them a strongly ‘Eastern’ feel. The records of writers such as Evans, and other contemporary paintings, maps and references to buildings in the city, although at least in part intended to show the bad state of the country in the last stages of Ottoman rule, provide a very useful (if incomplete) indication of how Sarajevo looked, worked and was lived in by its inhabitants in the years immediately preceding the occupation.4

They also show how the city and its people looked to the influx of military and civilian personnel on arrival in 1878 and indicate how the occupiers might have experienced what they saw and considered to be in need of improvement when compared with their Western standards.5 Unfortunately, it has not been possible to access Ottoman government records or travellers’ accounts for the immediate pre-occupation period, but the Western visitors’ tone is relatively negative (and at times superior). Their negativity can be seen in the context of the Western powers’ (self-) perceived role as the arbitrators and key players in ‘the Eastern question’.6 This ‘question’ had developed as a result of the increasing instability and weakness of Ottoman rule in the Balkans at the time, which affected Sarajevo’s economic prosperity.7 Friedrich Schlesinger, though he could be charged with commenting with hindsight, echoed this when writing on the economic development of Sarajevo for the directory Bosnischer Bote in 1902: ‘the impression created in the later part of the nineteenth century was that its previously significant prosperity must already have been declining for some time’.8

Sarajevo’s urban geography, so clearly described by Evans, would have contributed to his experience of its ‘otherness’ when compared to west-European cities. Partly owing to the natural boundaries supplied by the mountains and the relatively narrow flat area along the river, many streets were no more than 6 metres wide, without a clear building line; two-storey houses built on the surrounding hills were sited to get maximum light and followed the contours of the steep slopes.9 There were few public spaces such as squares, and most public life, almost exclusively involving men, was centred around the streets and, in particular, the market area, Baščaršija, with its small wooden shops and artisanal workshops. There were also public bath houses, segregated for men and women, hans in the market area where travellers and traders could stay for one night free of charge under vakuf endowments, and in every mahala, or district, a mosque, often small and built of wood, with its minaret and fountain outside for ritual washing.10 These physical characteristics were all part of what made Sarajevo a quintessentially Ottoman city.

Evans’ initial description of the city bears comparison with visual records of the time. Sir William Holmes, the ‘English consul’, painted a watercolour of Sarajevo from the west in 1864, which shows much of the detail described by Evans.11 This was later published as a postcard, demonstrating the popularity of both the subject and the vantage point. A photograph from the east, also made into a postcard later, is said to date from 1878 and similarly shows the minarets, domes and greenery, surrounded by mountains, with poplar trees along the banks of the river. In this photograph, the Gazi Husrev-beg mosque, the new Serbian Orthodox church, konak and military barracks are dominant features on the right and left banks of the river respectively, rising out clearly above the domestic buildings and smaller mosques which are at most two storeys high.12

Another watercolour painter who recorded Sarajevo much as it would have looked to visitors such as Evans, albeit post-occupation, was Lieutenant Eduard Loidolt, an officer in the Austro-Hungarian army, who was stationed in Sarajevo and other parts of Bosnia between September 1879 and September 1882.13 He too painted the low-level indigenous architecture, trees and incidental detail, helpfully labelling and numbering parts of many of his pictures to show what he had painted. His 1881 picture of the two bridges, which together spanned the Koševo stream by the Ali-Paša mosque, shows the wooden bridge structure with the stone bridge behind.14 These can also be seen in the Kataster map of 1882, which records Sarajevo much as it was before the Austro-Hungarian developments, and can be taken, with a few exceptions, to be a visual account of the city as it was when the occupiers first arrived.15 Its key gives an indication of the prevalence of greenery; there are symbols for orchards, vegetable gardens, ornamental gardens, scrubland, arable land, grazing land and meadow, and examples of all of these are to be seen throughout the map. Even in the centre of the city there were plenty of small orchards and vegetable gardens, often surrounded by walls. Many were subsequently built over during the following 30 years as land prices in the city centre rose and demand grew for more residential and retail space.

Other painted images of the pre-Austro-Hungarian city are to be found in Ljubica Mladenović’s work on painting in the nineteenth century.16 The book contains reproductions of watercolour sketches by war artists L. E. Petrović and Theodor Breidwiser [sic], showing battles in the streets of Sarajevo in 1878 when the occupying forces were struggling to take possession of the city. Although presumably intended as records of the fighting, they provide much incidental detail of key buildings and their surroundings. Petrović’s view of Alipašina džamija, Donja Hiseta i Musala (the Ali-Paša mosque, the Donja Hiseta area and the Musala) shows the area from the south, before the Miljacka and Koševo stream were regulated and the Landesregierung’s first administration building (now the presidency building) was built.17 Similarly, Breidwiser’s pictures of heavy fighting around the Magribija mosque and at Nadkovaći show how in the former case much, and in the latter, little, has changed since 1878.18 Mladenović also features J. J. Kirchner, another Austro-Hungarian officer, who stayed in Sarajevo between 1874 and 1884 and painted street scenes, some of which are reproduced.19 They show a more human scale and are full of busy people and animals, suggesting the intimate, semi-rural nature of the city centre before the occupation.

Urban spatial separation, including residential, trade and government features

As Evans notes, and these paintings illustrate, the pre-1878 city was dominated to the east by the old walled citadel with its fortress, on a steep hill above the bend in the river and commanding views westwards down the valley of the Miljacka to the plain.20 The Vratnik area (also known as ‘Grad’ or ‘Castell’), which is within the walled part, remains today much as it must have looked then, partly owing to the narrow and winding streets which are steeply inclined, making development of larger structures difficult.

To the west of this, also on a steep slope on the northern flank of the hills, is the Kovači area. The buildings here were, and remain, predominantly of the older, indigenous type; some have retained their orchards of plum trees, as were recorded in the Kataster map throughout the city in 1882. The streets are narrow here too, following the contours of the hillside, and houses are built on terraces, allowing views out across the valley. Among these were the houses of the élites, ‘the ruling caste’, as Evans put it. The Kataster map shows many vegetable gardens and orchards in both these areas, indicating a relatively low density of housing. Some small workshops are also attached to the plots, suggesting that the areas were not exclusively inhabited by the wealthy.

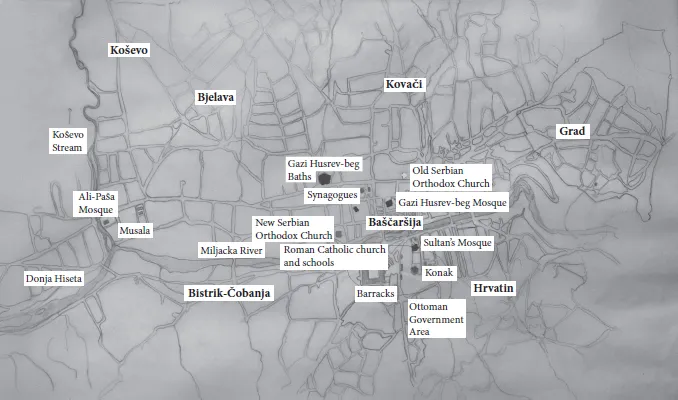

Figure 1.1 Sarajevo City map pre-1878 showing key areas. The chief area for post-occupation development was along the valley floor westwards from Baščaršija; this was made possible partly as a result of the regulation and embankment of the river in the 1880s and 1890s. Much of the housing on the surrounding hills remained relatively unchanged (for comparison, see Figure 2.1 in Chapter 2).

Source: Map based on Hartleben 1895, adapted.

Schlesinger agrees with Evans’ report on these higher, eastern areas being the preserve of the well-to-do Muslims, observing:

The valley floor with the densely-built Čaršija was little-inhabited by the well-to-do Mohammedan population; they preferred to settle on the neighbouring hills, surrounded by orchards and little groves. There were very few houses in Čaršija, which contained mainly shops and workshops, locked up and left at dusk.21

In saying this, he also emphasizes a key feature of the spatial organization of the city which was to change after 1878; the separation of residential and market and manufacturing areas. The post-occupation ‘Europeanization’ of parts of Sarajevo introduced the mix of ground-floor shops with apartment accommodation above; this was a major contrast to the ‘zoned’ Ottoman model.

In this period, Sarajevo still retained an important role as a trading centre for goods, as it was, in Evans’ words, at ‘the meeting place of the main roads leading to Austria, north of the Save, Dalmatia and Free Serbia, and being situate on the caravan route to Stamboul’.22 Ferdinand Hauptmann, in his major study of the Bosnian economy published in 1983, explains the city’s importance as a Stapelplatz (depot), providing storage not only for goods produced in Bosnia but also for Western goods going east to the Turkish provinces. He notes that the lack of passable roads and the difficulties of transport meant that most other places in Bosnia got their imported goods from Sarajevo, as they were not able to import them directly themselves; this was to change with improved communications following the occupation.23 Schlesinger refers to the difficulties for traders in his account of the pre-occupation ec...