![]()

Part I

Theory

Forethought

On Blackness and Time

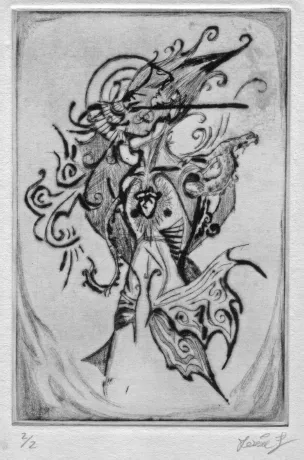

F.1 Becoming: A mythological portrayal of the black subject’s encounter with time and space, J.L. Fields, 2014.

There is the peculiar case of history—a loop passing as a science of time that, unless known, is certain to repeat. The saying is overlaid with a certain “doom” to motivate, to move knowledge along. The certainty history can be known as historical conceit. Knowing is taxonomy, classifying practices appearing as comprehensible orders. With the knowing—with all the slicing, cataloguing, and distributing—comes repetition. In other words, history does not repeat. Knowing history repeats it.

What, given significant history, happens to the unknown, the objects falling repeatedly, there, in-between historical procedures? How does one describe the interval between historical categories? “What” exists, there, caught between history and time?

Illumination begins in states of historical isolation. The subject catches fleeting glimpses out of the dark corners of the mind’s eye. Nothing can be done about it. Its mind rummages on its own, turning over while returning to the same thoughts. The realization of thinking about thinking stops the process—only to begin another loop.

Gradually, suddenly and all at once, the subject reaches for cognition. It is there, already, patiently waiting for a shift in perception, in order to see it. The iterative loop is the problem and the clue. When writing, redundancies are avoided to move the subject along. With thinking, incessant repetition is diagnosed as madness. In isolation, however, redundancy is essential. It is a measure of being.

Time is redundancy progressing. It has everything and nothing to do with nature—the rising and setting of the sun, the change of seasons. The “leap year,” for example, corrects the slippage between time (nature) and time (concept). Only within rarified scientific venues is time treated as an object of thinking, concept, and representation. If other iterative looping forms are noticed outside these contexts, they are misperceived, again and again, as mere repetition. Illumination comes while the subject/mind, now psyche, records objects falling, repeatedly, between successive historical periods. In other words, the mind/psyche is making time.

One can go on, and on, about time and miss the obvious shift in perception. The iterative looping—the recognition of objects, the making of time—cannot occur without a fixed interval. Time occurs in space. The term, space, means what it always means. It is the interval or absence occurring between a set of similar objects operating, perhaps, in succession and certainly in an arrangement. A musical score, for example, is a means to distribute sound and the absence of sound. The score’s concept evolves through an arrangement and distribution of space intervals. This distribution identifies sound and the absence of sound and confines them in suspense, in strict isolation. There is no moral harm in doing so. To bring music into being, this is what scores do.

The sound interval of the score, within the absence of sound in isolation, is where, spatially speaking, the mind/psyche records. Isolation is the spatial condition necessary for the mind/psyche to make time. Present prior to appearance and object, it is quintessential a priori. There is no perception, of any kind, without it.

While the mind/psyche ponders its objects and absence of objects—its own manifestation of time—it, along with the space interval it operates within, is the object of scrutiny. It, like the limits of its own looping concepts, is a fixed object of a time concept. That the mind/psyche can be contained by an abstract space interval of which it is becoming aware is the result of being conditioned by historical contemplations. Its persistent rise to consciousness allows for the production and arrangement of, among other things, time. By encountering the problem of making of time, it perceives a feature of space—and realizes it is inside.

With this cognition, the mind/psyche reasons by applying time to another thought:

Being ambivalent about the being “I,” it knows, already, thinking. “I am,” apparently, follows thought. In using its developing sense of time—the sense that things precede other things in a loop—it discerns something is missing. For the loop to be a loop, let alone iterative, it must arc between at least three things—the subject (i.e. I am), the perceiving subject (i.e. I Think), and the perceiving subject in isolation (i.e. missing). Turning the original phrase over and over in its new mind, it paraphrases a revelation:

The mind/psyche’s I/where?/there formulation speaks for the missing presence preceding the “I think.” It is akin to the absence of sound in isolation. No thinking can be done without it. It is being inside.

The mind/psyche thinks spatially. It contemplates objects, time, and “there” all at once. At the moment of being inside, it wonders how it looks. The thought recognizes the interior’s most significant quality, darkness. This darkness is so vast, ubiquitous, and opaque that “I think” and “I am” appear unaware.

With darkness comes the impossibility of its measurement. This is not to say that the space interval exists without dimension. As the mind/psyche’s thinking demonstrates, looping objects make time. The iterative loop cannot occur without the relative displacement of an object to itself or other objects. This “movement” occurs on a two-dimensional plane. Like time (nature) and time (concept), it is important to make a distinction between space and space. The flatness of space is its “natural” state. The “space” arising from it, literally and figuratively speaking, is a conceptual projection (of space). Space, in its natural state, is far more complex than the mind/psyche can comprehend and yet, contemplating in the midst of it all, it is inseparable from it. In other words, the mind/psyche is in a state of becoming black.

The “I am” raises a question. “Being flat, how does dark space within achieve any spatial complexity?” The question itself reveals an appetite for three-dimensional states. Being dark and flat, space, in its natural state, is infinitely more complex than appearance and/or projection. It is only there, bound to flatness, where thinking observes an object intersecting itself while passing “behind” another; or looping bodies having the capacity to “orbit” their selves.

While the Black Subject thinks from within, it conjures being “outside.” Here, it confronts history’s machinery, classifications, and categories—and the space interval’s situation of being confined, repeatedly, between categorical operations. For a moment, different “periods” seem to progress by building on prior periods. But this is not, from the perspective of the Black Subject, how history operates.

History’s means of measurement is based on what resides within it—not on mere chronology. It reconstructs a constant “original” and, by measuring itself against it, it advances. This advancing, called progress, only applies to being outside. Time on the inside collapses, again and again, back onto itself, creating rich, opaque densities in the confines of flatness. This is due to the “knowing history” process—a process where the historian, in providing proof of the advance, must always loop back to the named original fixed in time. Herein lies the potential undoing of all historical illusions and conceits—that is, to notice that as history advances it returns to the same subject in the same space at the same time.

An analogy is offered to make the scheme most clear. A blank musical score is not blank. It is filled with lines of musical staff representing infinite time and silence. The composer, in creating the composition, does not slice in to time or silence. The composition is superimposed. It is an overlay of sound. The composition arranges sound by returning to silence—the same silence that is there, underneath and behind, all along.

This too is the true nature of the historian knowing history. He externalizes himself by superimposing—by projecting on to the substrate of dark, flat space inhabited by the Black Subject. Knowing all along the flat substrate is not empty, he claims the original be compromised and devoid of proper history. He is mesmerized by the construction, believing the superimposition cancels-out contingency. But, the presence within necessitates repeated overlays. In pursuit of progress and period, the historian braves lifting his layered artifice to ensure “It” remains there—inside.

To this point the Black Subject has evolved, primarily, in its awareness. The making of time, the first breakthrough, is the result of persistent recognition. And now, deliberating in dark, flat space, it reasons whether something can be made from it. Realizing that the iterative loop restarts at the moment of thinking about thinking, it comprehends, suddenly, thought as object displaced from the mind. In other words, a thought is a projection of thinking. Turning this new-found concept to the predicament of being inside, the Black Subject reasons that infinite darkness and flatness are preconditions for projections (i.e. history, time, and space). The notion of being outside and inside history is a projection of historical thinking. Combined with making time, the Black Subject realizes it has been projecting all along.

The same thought emerges within consciousness full-blown. Projecting I/where?/there, spatially speaking, is making history. The Black Subject, now “It,” develops a strong, almost physical, sense—a craving—

i am outside of

history. i wish

i had some peanuts; it

looks hungry there in

its cage

i am inside of

history. its

hungrier than i

thot.

Ishmael Reed, “Dualism: In Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man”

(Conjure: Selected Poems, 1963–70 [Amherst, MA, 1972]: 50)

Introduction to Part I

Architecture in Black(2) Part I is a reprint of Architecture in Black, originally published in 2000 by the Athlone Press. This material, in the context of the expanded second edition, provides a cohesive semiotic evaluation of racial signs moving between historical and aesthetic classifications formulated by G. W. F. Hegel. Hegel’s edifice—its literary weight, its formulaic categories, its racial preoccupations—is transgressed by black semiotic theory. This paradigm, explicated by H. L. Gates, Jr’s The Signifying Monkey (1988), doubles as an analytical tool and aesthetic invention. It highlights, critiques, and revises vestiges of Hegelian racial motifs, signs, and so on in contemporary architectural discourse and theory.

An examination of dialectics is found in two texts: Hegel’s The Philosophy of History (1837) and Aesthetics (1835). The former demonstrates an anthropological construction of racial determinism in modern canonical history. The latter, through the negation and adaptation of racial (read: dialectical) categories, characterizes various art forms (e.g. poetry, painting, sculpture, architecture, etc.) as indicators of a race’s ability to signify Hegel’s ideal aesthetic system. Most important, the critique demonstrates the negative aesthetic affirmation of blackness and architecture.

Building on its critique, the text segues to a revision of Hegel’s dialectical system. First, the methodology defines Hegel’s edifice as a complex, yet closed, sign system. Second, by way of Saussurean semiotics, Hegel’s aesthetic model is objectified and subjected to the same dialectical process it proposes. By definition, its closed character gives way to Saussure’s arbitrary nature of the sign. The process results in the “discovery” of a unique form of racial consciousness (blackness) using arbitrariness in the production of language and cultural artifacts (e.g. poetry). The very existence of this black sign system, defined as the “black vernacular” by H. L. Gates, Jr, negates Hegel’s prima facie evidence that the flatness of blackness, in history and aesthetics represent innate inferiority.

The diagrammatic features of the dialectic and its counterpoint, the black vernacular, are examined in a series of architecture theory case studies. Seemingly banal nineteen-century debates on German architectural style are, in the context of the book, tautological extensions of racial/dialectical categories. Similarly, contemporary cases of architectural theory, in the call for new semiotic paradigms, are, in fact, describing H. L. Gates’s “black vernacular.” The situation demonstrates that even the most provocative and enlightened forms of architectural theory are compartmentalized, operating in strictly isolated territories. The case studies confirm Architecture in Black is the first to formally introduce architectural theory to black semiotic structures.

![]()

1

Hegel’s Tropes: History, Architecture, and the Black Subject

Philosophy and aesthetics: A total model of history

Hegel called architecture the mother of all arts: architecture was deemed autonomous and inclusive of all other fields such as music, fine art and theater performance. (by Arata Isozaki (Kojin, 1995: x))

A hut and the house of god presuppose inhabitants, men, images of gods, etc. and have been constructed for them. Thus in the first place a need is there, lying outside art. And its appropriate satisfaction has nothing to do with fine art and does not evoke any works of art . . . [W]e . . . have on our hands a division in the case of art and architecture. (Hegel (aesthetics), 1975: 632–3)

The citations chosen to begin this text represent the conundrum of historical writing in the context of architecture. lsozaki’s statement signifies a popular architectural myth—that architecture is the sum-total of the fine arts. Hegel, the father of modern history, debunks this myth and places architecture in its proper aesthetic place—a place outside art. Architecture overcomes this dilemma by skillfully misquoting and misapprehending Hegel’s system of aesthetics. But before placing Hegel’s statement in an absolute position of historical/aesthetic truth, let us assume that it too consciously constructs and conceals a similar error-making technique. In Hegel’s case, however, the technique is used to represent philosophy as history, and his aesthetic system signifies his idealized version of history. When architecture, as demonstrated by the first citation, erroneously embraces Hegel’s system of aesthetics (a philosophical/aesthetic system that is against the contingencies of architecture), the resulting relationship produces a logical and seductive series of historical and/or aesthetic errors. Even though the statements of the “architect” and the “philosopher” represent confrontational logics, they also represent a rare opportunity to suspend disbelief. Let us suppose I am a black author (I am), and I write about blackness (I do). Let us also suppose I have succumbed to a certain state of dementia causing me to see blackness everywhere—in history, in aesthetics, in architecture, in et cetera. What if I wanted to do some misreading and establish some black methodological errors of my own? How can I make sense of these two oppositional statements in terms of my black state of mind? Is it possible to construct a methodological intersection to demonstrate that Hegel’s aesthetic problem with architecture is, in reality, a philosophical problem with blackness?

To answer these questions, I will first proceed with a close reading of Hegel’s construction of history to verify the presence of historical anomalies. Second, I will demonstrate that these anomalies are, in fact, black racial tropes that Hegel constructs and places outside art and alongside architecture.

* * *

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770–1831), from his chair at the University of Berlin, delivered two sets of lectures that are of particular interest in establishing more concrete representations of history and aesthetics. An analysis of these texts is necessary to understand the comprehensive nature of Hegel’s ideas and reveals a distinct textual structure. This dialectical structure, independent of the content found within it, represents the same methodological device existing in both texts. In essence, it is a device existing between the two texts to be discussed. The first text, Lectures on the Philosophy of World History, was given from the winter semester of 1822–3 through the winter semester of 1830–1. Similarly, Aesthetics: Lectures on the Fine Arts was delivered in 1823, 1826, and 1828–9. These dates are important for three reasons. First, The Philosophy of History and Aesthetics demonstrate sustained levels of argument scholarship and intellectual inquiry maintained for 9 and 6 years, respectively. Because these texts were constructed as lectures, their respective arguments evolved concurrently and became more refined during the years in which they were presented (Fields, 2000: 169, note 3). Second, because they were produced by the same mind of the same individual at the same time, they should be considered evidence of simultaneous texts, one conveying explicit notions about race (The Philosophy of History), and the other about the fine arts and architecture (Aesthetics). The internal logics of both texts, as will be demonstrated, are highly complementary. One text (Aesthetics) represents the methodological/formal extension of the other (The Philosophy of History). Finally, although the lectures are discussed here in isolation, they must also be considered as significant examples of a broader range of historical and philosophical activity, including the rise of racial determinism characteristic of intellectual, philosophical, and historical discourse in the nineteenth century (Fields, 2000: 170, note 4). Given the comprehensive scheme of representation initiated by these texts, it i...