![]()

1

Building a Viable Society:

Our Positioning within the Field of Social Design

We believe that the expertise developed within the design discipline offers unique value to the process of seeking solutions for the complex challenges societies face today. And we believe there is a need to revise our practice of creating products, services and systems when we wish to create a more socially just and sustainable world. These positions are, in themselves, not new – they drive many of today’s design thinkers, scholars and practitioners. But to what extent and how these concerns affect their actual design practice can vary greatly. The design approach cultivated in this book falls into the realm of what is loosely called ‘social design’, a field to which many of these thinkers, scholars and practitioners belong – sometimes because they explicitly claim to be, and sometimes because others see them as important figures in this field.

The term ‘social design’ has been around for a while. Many refer to it as a particular branch of design. But when people say they study or practise social design, what they mean still remains unclear. This murkiness about its definition has not obstructed the rapid expansion we have seen in the field. An increasing number of design students, design schools, practitioners and scholars use the term to explain what they do. In fact, its conceptual ambiguity may be precisely the reason why social design has become so popular around the world: it allows for multiple interpretations and practices to develop in parallel. As a result, what social design means at the Politecnico di Milano (Polytechnic University of Milan) may have little to do with the work done at the Designing Out Crime centre in Sydney. And research in social design at Carnegie Mellon may share little theoretical ground with the social design work executed in the favelas of Brazil.

Since you have shown enough interest in this book to begin reading it, we suppose that you have come across the notion of social design before. You probably have a vague idea of what social design is, some hunch or maybe more of a hope for what it can do. It might also be the case that you have accurate knowledge of a particular view on the field, and maybe you even have professional experience in social design practice. Either way, to be able to understand our take on social design, first we have to find common ground together. This chapter is aimed at doing just that. It is intended to clarify the field of social design and bring order to the various ways in which it has manifested in designers’ and design scholars’ thinking, writings and actual practice. Not only will this chapter give you an overview of the field of social design, it will also serve to more clearly articulate how this book offers a unique contribution to it.

An historical account of social design

There is an important turn in design history that is often noted as the start of social design: the publication of Victor Papanek’s book Design for the Real World: Human Ecology and Social Change. The first step towards defining this evolving field is to understand how the industrial design discipline has changed in relation to this book.

All of design practice is continuously evolving. The image of a designer artfully crafting an object for somebody else single-handedly is a nostalgic view – it may have been accurate in the past, but today such practices have all but ceased to exist. The design practice of today exists within a complex web of relationships with a global outlook. Design thinkers, usability experts, trend watchers, marketers, programmers, design engineers, technicians, assemblers, distributors, suppliers and salespeople – to name just a few – all have a share in deciding what should be designed and how to get it ‘out there’. One of the major developments that stimulated this networked and distributed design cycle was the rise of mass production in the late nineteenth century. Rapid scaling of production paved the way for a whole new paradigm in design. More products could be produced for less money, meaning more convenience and comfort could be offered to more people. After the Second World War, this form of design really took off.

In his book (first published in 1971), Papanek warns against the consequences of commercializing design. He expresses his concerns about designers ‘confecting trivial “toys for adults”’ that people do not need, the depletion of resources their production would lead to and the piles of junk that would rise around the globe when such useless products are thrown away. Papanek saw how influential commercial design practice would become, and how much it would impact society at large as a result of the sheer magnitude of its scale and reach. As countermovement, he called upon designers to move away from commercial design, and instead be responsive to people’s ‘true needs’ (p. x). At the time, the book garnered more objection than support from Papanek’s peers, but today it has become a key reference work in the design field that has greatly inspired what we now call ‘sustainable design’, ‘humanitarian design’ and yes, ‘social design’.

What Papanek was attempting to advance was a design practice driven by ethical considerations. In this, Papanek was not the first. Design schools like Bauhaus and innovators like Buckminster Fuller had also proposed using design as a means to create a better world – a fact that served to stimulate ideological and ethical considerations in practice. But instead of optimizing commercial design in the ethical sense, or repositioning design as a local, artisanal practice, Design for the Real World pled for a radical new kind of design practice. Admittedly though, Papanek gave very little guidance as to what this practice could or should look like. So just how much the new forms of design practice that developed from that point onwards can really be attributed to Papanek’s thinking remains debatable. Yet it is fair to say his book continues to be an important inspiration for many. Is it possible to track the ways that design has become more socially responsible or ethically just, starting from the time of the book’s publication?

Before we can do so, it is important to recall that the design profession was primarily focused on ‘the object’ at the time. The outcomes of design activity were tangible – things you could drop on the floor. Artefacts like that – be they chairs, washing machines, cupboards, pencils or typewriters – were clear nodes between two systems: the production system that fabricated the product and the system of use in which the thing had a meaning. At that time, these two systems existed independently from one another, and it was the designer who had to mediate between them. Design became the pumping heart of capitalism devoted to making commodities that could be sold. Capitalism worked with ‘markets’ and success was measured through sales numbers. But as soon as the product was sold, its system of use began to evolve – a system in which the product was related to by its owner, created desire in others, mediated behaviours via its use and co-shaped cultures. Many industrial products changed societies in ways we can only recognize in hindsight. Many of these changes happened the way Papanek predicted. His book was a call to take the societal impact of design seriously and to account for it within professional design practice.

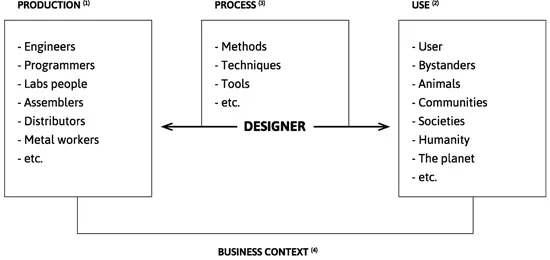

Figure 1.1 is a schematic depiction of industrial design practice in the 1970s. In it, the designer – armed with tools and methods – mediates between the system of production and the system of use. When creatively and conceptually giving form to an artefact1, the designer must somehow align his knowledge of both systems. In the 1970s, the job was primarily guided by commercial principles, which meant that – to put it bluntly – designers were geared to understand the system of production in terms of efficiency and cost-reduction, and the system of use in terms of market opportunities and sales. The main focus for commercial design practice has been, and is, individual needs and desires.

FIGURE 1.1 Schematic representation of the industrial design practice in the 1970s.

So how exactly have industrial design practices become more socially responsible, and when did this happen? In hindsight, and to the best of our knowledge, we see four pathways that have been taken by the design scholars and practitioners of the discipline. Each pathway focuses on one of the four building blocks of industrial design practice: (1) the production system, (2) the system of use, (3) the design process or (4) the business context. Each of these components of industrial design practice has undergone changes intended to improve it in ethical terms. However, some developments have been more explicitly inspired by the work of Papanek than others. In the coming sections, we will discuss the development of industrial design practice along these four lines. Since it is our aim to give an overview, we only discuss these developments in general terms and highlight those we see as essential.

Responsible production

One could say that the practice of responsible production is guided by a question: how to account for the ways that production impacts people and the planet (Plates 3–5)?

What we see here is an effort to make production more sustainable and socially equitable, minimize the detrimental effects of production principles and direct product production towards improving people’s lives. Emphasis has been placed on the systemic nature of production, meaning that its separate stages need to be considered as a whole to lower its carbon footprint. Nowadays, design students are taught how to carry out ‘lifecycle analyses’ to minimize the environmental and social impact of a product throughout its life – from production to use to disposal. This entails making conscious choices about materials, production facilities, assembly, distribution channels and disposal options (for example, see Giudice, La Rosa, & Risitano, 2006). This development has been bolstered in recent years by the arrival of the ‘cradle-to-cradle’ approach, introduced by Michael Braungart and William McDonough (2002), which promotes using production materials and techniques holistically, in ways that both integrate and imitate natural processes. Striving for cradle-to-cradle design prevents harmful environmental burdens and can even provide economic growth to people who need it the most, they explain. And indeed, there are an increasing number of brands producing goods in tandem with specific groups in order to transform and empower the role they play in society. For example, Indian women from marginalized communities who take part in design production initiatives can work towards financial independence, and prison inmates who learn a trade can more easily enter the workforce after their release.2

The social and environmental impact made by the system of production is clearly being addressed in the aforementioned methods. But the practice of responsible production has asked very little from the user – or ‘consumer’ in the consumerist paradigm. At best, consumers learn how their purchases might (positively) affect communities and the planet from the explicit labelling on responsible products. This means consumers can make better, more responsible choices. However, as of now, advances in thinking about creating and sustaining a circular economy explain more dramatic changes on the consumption side. Based on new types of business models, people are encouraged to share products or repair them in case of failure instead of demanding new ones as service (Bocken et al., 2016). This shows that while responsible production practices may have started off by focusing mainly on the system of production, scholars and practitioners have gradually expanded their focus to include the system of use – not merely as a consequence of the production system where people adopt (or do not adopt) responsibly produced products, but more and more as a system that has potential to be the driver for more sustainable production principles.

Anticipating the social consequences of use

This development within industrial design practice is guided by a different question: how can a design prevent the undesired effects of its use, or how can we create ‘better’ effects for people and the planet (Plates 6–8)?

Today’s design practitioners are (mostly) well aware of the myriad, complex ways that products affect their users. The choices a designer makes about the form a particular product takes determine how people understand it and make use of it. Design considers how safely a product can be used, the kinds of emotions it can elicit and, ultimately, users’ overall experiences when interacting with it (e.g. Schifferstein & Hekkert, 2008). Anticipating users’ responses to products and services is fundamental in user-centred design, the prevailing paradigm in design today.

Although perhaps not in direct reference to Papanek, designers and especially design scholars are gradually expanding their scope by considering the longer-term consequences of product use. First of all, scholars no longer solely focus on the moment of use; researchers are looking at how product use may affect people’s subsequent actions, the life decisions they make and sustain and, ultimately, the impact use can have on users’ long-term well-being. For instance, user experience researchers are looking beyond hedonic tone to see how an artefact can foster long-term happiness for users instead (for example, see Desmet & Pohlmeyer, 2013; Hassenzahl, 2010). And the field of behaviour change is especially expanding its reach in the healthcare domain to improve people’s well-being in the long run. Products and services are being developed and tested that help people comply with necessary medical routines (for example, see De Oliveira, Cherubini, & Oliver, 2010), alter their lifestyles due to chronic illness (for example, see Klasjna et al., 2009), cope with bereavement (for example, see Massimi & Baecker, 2011) or recover from mental illnesses (for example, see Jongeneel et al., 2018). An important reference is the work of B.J. Fogg, who introduced the approach of using persuasive technology to design for behaviour change (Fogg, 2003).

Secondly, there are a growing variety of perspectives the designer can take to consider the consequences of use. Beyond creating user value, designers are considering how artefact use might affect others and the environment. Many will be familiar with design approaches that seek to prevent undesired consequences. However, some design scholars have begun to look at ways to anticipate desirable effects from a social and environmental perspective. For instance, Kristina Niedderer (2007) explores artefact characteristics that evoke mindful social interactions. And there are many scholars seeking ways to elicit more sustainable behaviours through design (for example, see Lockton et al., 2008). Some are looking for triggers that activate responsible waste disposal behaviour (for example, see De Kort, McCalley, & Midden, 2008), prompt people to waste less food (for example, see Lim et al., 2017) or help people make more sustainable transportation choices (for example, see Laschke et al., 2014).

Thirdly, and more recently, design scholars have begun to look for ways they can account for social consequences that arise over time. For instance, practice-oriented design – which is based on Elizabeth Shove and her colleagues’ (2007) social practice theory – addresses the interconnectivity of design and cultural factors, and how this can shape behaviour over time (see also Pierce et al., 2013). Although the scope of design is gradually being widened to consider the social and longer-term consequences of artefact use, such exploration is still at the formative stage and remains largely an academic endeavour.

Democratization of the design process

A further responsible turn within design practice is guided by another question: how can those affected by a design outcome have a say in what is being produced in the first place (Plates 9–11)?

Papanek argued that everybody could design. After the Second World War, a do-it-yourself (DIY) mentality developed in various countries. The British government was already encouraging people to do the things that skilled labourers had been doing before the war started. Books like Man About the House were written to help the general public participate in finishing and building houses around the country (Hunot, 1946). At the same time, but with a different impetus, the DIY-hype in the United States took off. War had taught American men and women new technical skills and given them the confidence to build their domestic lives as they wished (Goldstein, 1998). Atkinson (2006) explains that whether one engages in DIY because of financial reasons or for self-expression, all forms act as agents of democratization by ‘giving people independence and self-reliance [and] freedom from professional help’. Democratic principles and freedom are key...