![]()

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION

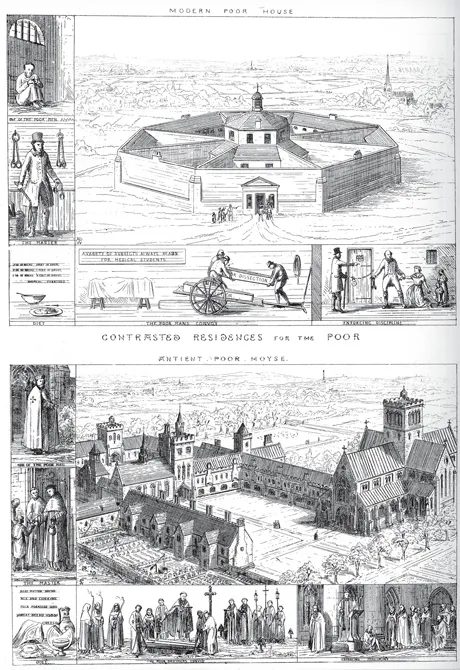

Augustus Welby Pugin, leader of the Gothic Revival in Britain, was a key figure in proposing a link between architecture and society, but he was perhaps more effective with his drawings than with his writings or buildings. In his book Contrasts of 1836 he set out to prove the virtue of fourteenth-century Gothic in comparison with what he regarded as the degraded architecture of his own day, but much of the textual argument is about the Reformation, polemical rather than factual, and no longer pertinent or credible, so we scarcely attend to it today. The drawings, though, still resonate (Figure 1.1). Here we are shown comparative poor houses: above is a parody of the workhouse, playing on the utilitarian philosopher Jeremy Bentham’s panoptican concept,1 below an idealized depiction of a medieval hospice. Quite as interesting as the views of the buildings themselves are the marginal scenes of life within them, presented like a strip cartoon around the edge. Top left in each case shows one of the poor men, the modern one apparently in a prison with a high barred window sitting in a state of relative undress on straw, while his medieval counterpart stands cloaked and hatted before the church door. Moving on down, Pugin depicts the master: the top-hatted modern one brandishing a cat-o’-nine-tails with manacles on the wall, while the medieval one is a priest ministering to a woman and child, again at the church door. The lower strips show other aspects of life: a diet of thin gruel as opposed to bread, cheese, ham and ale; a body being taken away for dissection as opposed to receiving a Christian burial; and the enforcement of discipline in the modern case with prison, chains, and force, in the medieval one with admonishment from the pulpit towards good behaviour. The polemic is visually compelling, all the more so for its almost Dickensian satire and social concern, and the twenty-four-year-old Pugin was surprisingly astute in the choice of things to connect with architecture: food, clothes, discipline, and the death ritual (or lack of it in the modern case). It was a knowing choice, and one that would satisfy a modern anthropologist. Food is not only considered an essential factor in establishing human society,2 but also involves taste, not by mere accident the key term used for aesthetic judgement. Clothes are indicators of social position and rank, as explained in the almost contemporary anti-utilitarian book Sartor Resartus by Thomas Carlyle, though we do not know whether Pugin read it.3 Discipline is the common instrument of social control and was to become by the mid-twentieth century the focal point of Foucault’s revolution in theory.4 Burying the dead has long been considered a defining characteristic of humanity.5 Some of Pugin’s points might have been substantiated with carefully chosen evidence, but he had neither the time nor the patience to gather it, and the images poured out of his fervent imagination.6 All who feel the efficacy of architecture might concur with the sentiment, but the connection is objectively hard to substantiate.

Figure 1.1 Contrasted ‘residences for the poor’ from A. W. N. Pugin’s book Contrasts of 1836.

Beyond the ‘merely functional’

This is a book about how architecture affects people’s lives. It will attempt to penetrate beyond traditional assumptions about utility, style and aesthetic effect to deal with the implicit, with the way that architecture shapes our experience without our conscious awareness. It will show that by providing a background for our lives, buildings tacitly suggest and sustain a classification of people and things that contributes to the constitution of a shared reality. Buildings do this not just through coded decoration or intentional aesthetic message – though these may be part of the story – but more essentially by how they are used, and by the meanings established during use, during the relationships that people enact with them. Accepting that buildings have some kind of shaping influence on life is not to say that architecture determines behaviour, or that ‘form follows function’, as Louis Sullivan so simply and famously put it.7 By suggesting a kind of hand-to-glove fit, this oversimplified formula based on the Darwinian evolutionary principle concealed a much more complex interaction between people and their habitat.8 Most buildings apart from prisons are not physically coercive, nor do they force people to behave in particular ways, yet all buildings limit the available possibilities and can by their organization suggest or persuade towards particular courses of action.9 To give a simple example, whether you enter a theatre by the box-office or the stage door confirms your role as spectator or actor, dividing spatially between separated frontstage and backstage worlds which reinforce those roles, so obliging you to behave as one or the other. Failure to comply with these conventions is almost unthinkable, as we know that it is ‘not our place’ to presume to enter by the stage door, just as we should not enter the main door without a ticket or inappropriately dressed.

But how far does this go? My teacher James Gowan, no stranger to functionalist planning concepts, once rebuked me for erring in the determinist direction by declaring sceptically: ‘I can eat a sandwich in a room of any shape: you try me!’10 As a student I was somewhat floored by this and never took him up on his offer, but I think it would be possible to create a room nasty enough to put him off his sandwich. More to the point, most people would agree that some rooms are better to eat sandwiches in than others, even if Gowan had cunningly chosen an activity that tends to be independent of site.11 The relationship between space and activity is evidently neither a compelling certainty nor open and random, but complex and variable. What makes it so hard to pin down is that it is a two-way process involving a ‘reading’ as well as a ‘doing’, so that there must be some complicity between user and building. In other words the arrangement of the building has somehow to mesh with a set of habits, beliefs, and expectations held by the person who experiences and uses it, a matter of what Marcel Mauss and Pierre Bourdieu have called the ‘habitus’.12

Once such ‘meshing’ between spaces and rituals of use is achieved, buildings and activities tend to reinforce each other, for besides the sheer convenience of ‘fit’, buildings go on to reassure their users by reinforcing their beliefs and intentions, substantiating their world. Buildings provide prompts for action and frameworks to define relationships with fellow human beings in forming societies or communities. This is why variations in buildings and social practices expose differences in understanding and in conceptions of the world, causing the questioning of things normally taken for granted. The naming of rooms, for example is but the tip of an iceberg of classification rooted in language, perception, and in the metaphorical construction by which shared worlds are ordered. Beyond the question of rooms lie greater differences in spatial usages and the application of meaning, differences one could never guess at without knowledge of practices. And buildings reflect not only relationships between persons but also those between humans and deities, humans and cosmos. In many if not most pre-modern societies practical tasks embraced a religious and cosmological dimension, allowing no clear division between the utilitarian and the ceremonial. In summary, buildings provide a mirror that reflects our world, our knowledge about it, and the way we interact with it.

This was well understood by William Lethaby, Pugin’s inheritor and the most serious architectural theorist of the following generation, who pushed the link between architecture and society further. The pursuit of ‘style pretences’ was, according to him, all wrong. ‘Art is the well-doing of what needs doing’,13 he said repeatedly, and he found in farm carts and hayricks objects of beauty, the way of finishing a loaf of bread a source of local pride and identity. Even in gardening ‘great thought is given to laying out cottage vegetable gardens to get the rows straight and right’.14 The well-organized and skilful activity knowingly done produces a beautiful and poetic result, which is ‘shipshape’ and ‘tidy’, two of Lethaby’s favourite words of approval. This spirit can also rise into communal celebration in ‘work festivals’ which mark calendrical events like harvests and raise work to the level of play: ‘almost a ritual’ he says at one point, taking the word in its usual narrow sense.15 But Lethaby also perceived the link between architecture and cosmology. In the most original of all his written works, Architecture, Mysticism and Myth, a cross-cultural survey by an architect drawing for the first time on the discipline of anthropology, he sought the basis of architectural order in the beliefs and cosmologies of the peoples concerned. In the preface to the later version, Architecture, Nature and Magic published in 1928, he claimed: ‘The main thesis that the development of building practice and ideas of the world structure acted and reacted on one another I still believe to be sound’.16 An abundance of evidence accumulated by anthropologists and historians since Lethaby’s time supports his basic thesis and the validity of his pioneering enterprise, if undermining some of the detail.

Architecture as memory and as promise

A further complication of the way architecture reflects society is the element of time and memory. The space–activity relationship does not simply and nakedly exist at a particular moment as the phrase ‘form follows function’ seems to imply, but is necessarily more protracted, involving duration, memory, and anticipation. The sense of duration, so easily overlooked, is essential to consciousness, for we have to locate ourselves in time and are always aware of temporal relations beyond the present instant.17 A simple illustration of this is the experience of music: hearing a single note means little, for it is the relation of notes that matters and the way they unfold in time, which we have to ‘bear in mind’ in order to experience it.18 A parallel in architecture is the need to walk around and through a building to experience it while at the same time somehow constructing in mind an idea of the whole. We generally use the word ‘memory’ for a rather longer term process, but...