![]()

Part One

Political and Economic Dimensions of Identity Constructions in the Linguistic Landscape

1

Turbulent Linguistic Landscapes and the Semiotics of Citizenship1

Christopher Stroud

1 Introduction

When encounters take place in contexts of contest and division, representations and plays of identity in public spaces may be heightened or erased. Such encounters take particularly acute forms in the cramped spaces of the periphery. Here, sociopolitical and economic constraints, together with histories of displacement and disempowerment of groups and individuals, turn the novelty and uncertainty typical of interactions across difference into fuel for tension and conflict. This is the case for South Africa, where historically what types of bodies could circulate in what places was severely regimented and heavily policed. Today, twenty years after the transition from apartheid to democracy, South Africa is a restless society in the midst of extensive transformation. Despite this, contemporary legacies of apartheid find expression in xenophobic violence against in-migrating Africans, in the many service delivery protests taking place in townships across the country, as well as in local struggles over land redistribution and ownership.

One contemporary expression of apartheid racialization has to do with what places people ‘feel at home’ in, and to what extent they share a common perception of place across racial and social boundaries. To a large extent, the history of apartheid segregated place still ‘shape/s/ how bodies surface’ (Ahmed, 2007: p. 154), as ‘bodies remember such histories [colonialism/apartheid, my insertion], even when we forget them’ (Ahmed, 2007: p. 154). Issues of ‘belonging’, ‘community’ and ‘identification’ with a particular space(s) are a key dynamic in the ‘complex nature of [South Africa’s] multiculturalism as place sharing, of cross cultural interaction or multiculturalism of inhabitance’ (Wise, 2005: p. 171). Feeling in or out of place is one of the main determinants behind whether individuals are able to exercise agency and local participation, as well as whether encounters across difference are expressed as contest or conviviality. Such a sense of place is very much an embodied sensitivity, with Ahmed noting how:

People inhabit, appropriate and perform their embodied, emplaced and mobile selves against the backdrop of linguistic or semiotic landscapes, with diversities of bodies in place often reflected in the complexities of their linguistic and material representation.2 Because LLs provide the discourses and important reference points by means of which people make sense of local place (Leeman and Modan, 2009; Stroud and Jegels, 2014), the challenges confronting a sociolinguistically informed politics of place are those of heeding the plural voices layered into, or erased out of, the semiotic landscape (Mac Giolla Chríost, 2007; Shohamy and Gorter, 2008; Woldemariam and Lanza, 2014 a, b). This chapter is an investigation into how LLs are actively deployed by groups and individuals to enhance local engagement, sense of belonging or acts of resistance, and to create conditions for new emotional geographies of place. In this sense, the chapter highlights how stances on self and the identities emerging out of contested positionalities in place are layered into LLs, and how they reflect landscapes as a ‘place of affect’ (Jaworski and Thurlow, 2010). Two illustrations from the South African context are used to develop this point. The first case study explores how a sense of place and its semiotics is construed around the bodies that inhabit them. The second illustration suggests ways in which bodies may be incited to be by the semiotic landscapes they inhabit, that is, how LLs contribute to individuals’ corporeal fit and manifest identities in place. The two case studies reveal the tight linkages between semiotic landscapes and the politics of place, suggesting ways in which multi-semiotic, linguistic, practices are used for dynamic and novel forms of citizenship. Importantly, the chapter argues for framing an analysis of a politics of place in terms of productive, temporally layered and extended juxtapositions of competing discourses about how place should be represented and owned. By way of discussion, I offer the notion of turbulence as a potentially innovative way of capturing such a dynamic, and attempt to draw out some implications of a ‘turbulent’ analysis for approaches to LLs.

2 Political phenomenologies of LLs

Local places hosting local interactions comprise important sites for the unfolding of political dynamics and the performance of citizenship. Bourdieu, for instance, has emphasized how local interactions can be ‘sites of struggle of competing and contradictory representations [with] a potential to change dominant classifications’ (quoted in Chouliaraki and Fairclough, 1999: p. 105), and Besnier (2009: p. 11) alerts us to how ‘politics happens where one may be led to least expect it – in the nooks and crannies of everyday life, outside of institutionalized contexts’. Isin (2009: p. 371), in the same vein, invites us to consider the increasing importance of the politics of the ordinary, introducing the notion of ‘acts of citizenship’ to refer to those ‘deeds by which actors constitute themselves (and others) as subjects of rights’. Acts of citizenship take place in new sites outside of the conventionally political, such as demonstrations, theatre performances and the like. Places where many diverse types of actor jostle, such as local bars, streets and public spaces, comprise saturated sites of difference. Not surprisingly, ‘acts of citizenship’ in such sites are about the enactment of various forms of conviviality or contest with others, creating inclusiveness or resisting marginalization.

However, it is also through acts of citizenship that the practical achievement of place-making itself is achieved. Nayak (2010: p. 2372) explains how people’s sense of place is informed by, and encapsulates, ‘ideas of nation, region, home or locality as geographically located and emotionally expressed’, and Mondada (2011: p. 291) stresses ‘the importance of social action for the making of space’, and the need to highlight ‘the details of the embodied production of these voices in and on space as well as of the controversial nature of plural versions of space’. Casey (1997) proposes the notions of ‘thick’ and ‘thin’ places to capture the different quality of places; ‘thick places become repositories of the self’s concernful absorption’, whereas ‘thin’ places ‘offer nothing to hold the self in place, and no memorable or resonant command of placial experience’ (Duff, 2010: p. 882). Through processes of ‘affective rendering’ (or ‘acts of citizenship’) that inscribe privacy, belonging, ownership and community onto public spaces, thin places can be transformed into thick places. Linguistic landscaping is one powerful means of affective rendering, comprising acts of citizenship that, together with practices such as graffiti writing, planting of gardens and the like, mediate the production of thick places.

Such a dynamic, practice or process-oriented approach to place-making fits well with recent social theorizing that recognizes and builds on the inherent mobility and fluidity of social processes more generally – a perspective also adopted in the sociolinguistics of mobility (e.g. Blommaert, 2013). This vantage point invites us to consider a dynamic account of space, text and interactions in the semiotic production and politics of place, where individuals are part of ‘a fluid, urban semiotic space, and produce meaning as they move, write, read and travel’ (Pennycook, 2010: p. 148; cf. Jaworski, 2014). This in turn requires a methodology that can capture how signage is affectively embodied and enacted through everyday practices of place-making (De Certeau, 1984; Lee, 2004; Hall, 2009; Leeman and Modan, 2009; Malinowski, 2009; Trumper-Hecht, 2010). A praxeological approach takes participants’ practices in interaction as a point of departure, detailing how discursive versions of urban space unfold through social interaction, where participants orient to specific spatial, situated material and embodied features of the environment (Mondada, 2011; Stroud and Jegels, 2014). In a study of the troubled township of Manenberg in South Africa’s Western Cape, Stroud and Jegels (2014) discuss how a multivocal (and sometimes contested) sense of place unfolded in concrete social encounters as the residents of Manenberg offered up interactionally negotiated narratives of crime, security, freedom of movement, aspiration and futurity. As they spoke of the precarity of life in the township and their hopes and aspirations for the future, they organized their tellings in narrative frames that were built around the incorporation of artefacts of local LLs, thus ‘orient/ing/ to specific spatial, situated, material and embodied features of the environment, making them relevant for the situated organization and achievement of the encounter’ (Mondada, 2011: p. 291). In the following, I attempt to develop this approach further towards the politics of place, making use of two case studies as illustration. The first study explores how those who inhabit or move through a place contribute to the ‘design’ or ‘sense of place’, that is, how semiotic landscapes engage with bodies. The second study discusses how bodies themselves are engaged by landscapes, that is, the impact of semiotic landscapes on inciting the body to a sense of belonging or displacement in place. Ultimately, both case studies contribute to answering the question of how landscapes might be transformed, so that bodies can inhabit and move in place differently.

3 Bodies engaging place

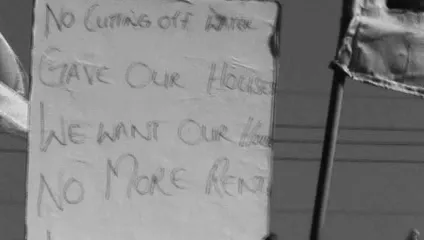

The first case study is of a protest march that is initially and ostensibly against poor service delivery, evictions and lack of housing. In angrily protesting against their harsh living conditions, the protesters are using a variety of semiotic means such as T-shirts and placards to engender a collective affect (Rojo, 2014). At the same time, they are also creating a particular representation of ‘place’. In fact, what we witness most vividly in this turbulent event is how a sense of place-ness emerges out of the act of citizenship carried in the protest. The complex semiotics of the march, comprising artefacts of the LL, are integral, not only to the representation of place but also to its (re)production. Furthermore, as we shall see, what is particularly interesting here is that what was originally a service-delivery protest against rent hikes and eviction morphs over time and as the march unfolds into an occupy movement. The target of the occupy movement is the end-point of the march, Rondebosch Common, one of the affluent southern suburbs of Cape Town. This is a historically white suburb that has over decades acquired the ‘shape of the bodies’ (Ahmed, 2007: p. 156) that have historically inhabited it – large houses, clean open spaces and tree-lined avenues testify to the socioeconomic privileges of its exclusively white inhabitants. The excluded bodies of the marchers are loudly contesting this privilege, although the (re)production of Rondebosch Common during the protest as a place of racialized trespass is not the initial purpose of the march but one that emerges out of an un-orchestrated shift of emphasis in the way the march event develops.

Figure 1.1 is a piece of the LL comprising handwritten placards in English, demanding in loud, red, block letters an end to rent and that household water not be cut off.

The artefacts, and others like it, are part of a multivocal act of citizenship comprising chants and slogans delivered in a variety of languages – English, isiXhosa and Cape Flats Afrikaans – where some of the performances can trace their origins to anti-apartheid protests in the 1980s and earlier. One such manifestation illustrated in Figure 1.2 is the burning of rent arrears’ papers, designed to pull up memories of the Sharpeville massacre’s burning of pass-books.

Used here, the burning of the documents (an insertion of an LL artefact made prominent by its very erasure) transposes critiques of the constrained mobility of the recent apartheid past into the marchers’ current critique of constraining living conditions. This action contributes a chronotopical structure to the protest march, where the specific spatio-temporal event of the massacre, an event that is inundated with historical significance and that arouses strong affect, serves to lend legitimacy, integrity and historical credence to the marchers.

Figure 1.1 A placard for an English public sphere of protest.

Figure 1.2 Burning the rent arrears papers.

When the march was still primarily about rents and possible evictions, marchers appeared to be less strictly organized: the banners they carried, the languages and slogans they displayed and the clothing they wore were heterogeneous and diverse. However, in the actual march itself (Figure 1.3), we find a gradual uniformization of the clothing, banners and slogans, and that signage has shifted from being multilingual, to monolingual.

Out of an initial diversity of messages dealing with rent hikes, electricity outage, water grievances and evictions, only one single political message is promoted, namely the black lettering UDF on a yellow background, invoking the old struggle organization, the United Democratic Front. The LLs of placards and clothing reflect a ‘compacting’ of the march, and a smoothing of the jumble of multivocality, bodies and language into one ‘voice’. This contributes to the emergence of a ‘uniform public space’ of serious, focused and orderly political engagement (cf. Ben-Rafael, Shohamy, Amara and Trumper-Hecht, 2006).

Figure 1.3 Disciplined and uniformed marchers.

It is unclear at what point in the march the sequence of events shift or tip from an initial emphasis on a protest against evictions to one where Rondebosch Common becomes the target of a symbolic occupation and re-imagined as a multiracial and inclusive space. In one way, it appears to be a parallel – if still subordinate – thematic of the protest, one that emerges more tangibly as the march gathers momentum. In the course of the march, Rondebosch Common is increasingly represented as a place of racial trespass, when the protesters, many of them so-called back-yard dwellers accuse the white residents themselves of being ‘back-yard dwellers’, in other words, illegitimate occupants, thereby unsettling the legitimacy and rejecting the exclusivity of the white bodies that have historically shaped the sense of...