![]()

1

INTRODUCTION: INDIAN FASHION

In the summer of 2010, while conducting field research on fashion designers in New Delhi, I happened to spot a middle-aged Punjabi1 lady shopping for vegetables in South Delhi’s Kailash Colony2 market wearing a Kota sari with bright green classic Crocs. At first, the sight was jarring, as I had by other association always considered Crocs to be distinctly ungraceful and certainly not something that I expected to see paired with a sari. However, upon further reflection and acclimatization to the rhythm of everyday life in India, this initially unusual pairing of two geographically distinct items no longer seemed odd. Instead it accurately represented the unique nature of contemporary urban fashion that features vibrant juxtapositions of local styles with global trends and traditional dress practices alongside Western influences and international brands—where designer churidars get accessorized with Jimmy Choo Cosma clutches, Ikat kurtas liven up purani (old) Levis jeans, leather juttis stay cozy with argyle socks and zip front wool cardigans can be worn to match the shades of almost any type of sari.

That same summer, much to the delight of Delhi’s fashion bloggers, international store Zara was having its first seasonal sale in India. Zara had only recently opened stores in Delhi and Mumbai and the lines for the trial rooms at its City Select Mall location snaked around the store. For those who couldn’t afford the marked down sale prices it was an opportunity to look and try, and then find similar styles at Sarojini Nagar’s streetside export surplus stalls.

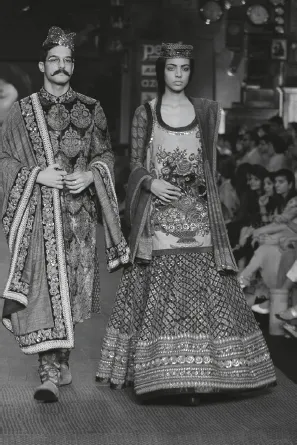

Around the same time, on yet another end of the fashion spectrum, a select group of Indian designers were showcasing their interpretation of Indian couture at the 2010 Pearls Infrastructure Delhi Couture Fashion Week. Though a formalized couture week at that time was a relatively new addition to the annual fashion event calendar, the alignment of traditional dress practices with a reinterpretation of couture to suit the Indian palette had already become a well established and profitable strategy. The platform of Indian couture had not only brought indigenous crafts and handloom textiles to the forefront, but also further ensured the continued relevance of traditional clothing styles within the arena of high fashion. The highlights from 2010’s couture week included the launch of JJ Valaya’s signature Alika jacket—positioned to rival the iconic Chanel suit. Gaurav Gupta’s models walked down the ramp to a remixed version of the popular Indian children’s rhyme machhli jal ki rani hai,3 while audiences gasped upon seeing his infamous sari and lehenga gowns embellished with deconstructed Swarovski crystals. Bollywood designer Manish Malhotra’s exuberant anarkalis had a Spanish influence, while Sabyasachi Mukherjee’s much anticipated catwalk show titled Aparajito4 (the unvanquished) opened with the national anthem followed by scenes from the film 1947 Earth5 in the backdrop. Sabyasachi’s collection exuded a deep nostalgia for the grandeur of India past—its textile heritage, royal ensembles and style icons (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Two looks from Sabyasachi Mukherjee’s 2010 Couture Collection titled Aparajito. Showcased at the 2010 Pearls Infrastructure Delhi Couture Week. Image courtesy Sabyasachi Mukherjee.

This was emphasized through his use of rich muted colors and tarnished embellishments that made the garments appear vintage. The overall style of the garments was primarily traditiona—lehengas, saris, anarkalis, achkans, angrakhas, cholis, to name a few—the cuts of which were reminiscent of Mughal court ensembles. Positioned as an “epic tale in Indian handloom, khadi and Zardozi”6 the collection featured an impressive array of textiles and embellishments sourced from many different parts of India. These included block-prints from Rajasthan, Kalamkari from Andhra Pradesh, aged Zardozi and badla work, and a variety of other handloom textiles decadently layered over each other. Most notable, however, was the fact that 80 percent of the collection was comprised of khadi.

Mukherjee’s use and transformation of khadi as a luxury material for creating couture was not only a thematic decision but also a strategic one—as a statement on the importance of preserving traditional dress and textiles, as well as asserting a sense of distinction for Indian design and fashion. Furthermore, the collection’s promotion of Indian handloom also served to underscore his mission to “save the saree.”

As indicated by the assortment of vignettes above, the past two decades have witnessed a sea change in the consumption, display, performance, composition and design of fashion in India. The catalyst for much of this can be traced back to the early 1990s and the large-scale economic reforms initiated by the Indian government at that time. Referred to as India’s economic liberalization, these reforms were aimed towards making the economy more dynamic, progressive and globally competitive. This period, and the years following, witnessed a marked shift from earlier socialist policies that India had adhered to soon after it gained independence in 1947. While the older political viewpoint focused on modernization and industrial development with a protectionist approach that stressed self-reliance and social justice, India’s new neo-liberal policies included an openness to international trade and investment, deregulation, tax reforms, initiation of privatization and various inflation-controlling measures.

Broadly speaking, these policies involved extensive attitudinal changes not only from an economic and political perspective, but also on a socio-cultural level across various strata of Indian society. Through generating new kinds of professional opportunities with increased financial gains, the reforms had a profound impact on the profile of the emerging elite and middle-classes in India, who were now also subject to new ideologies of progress and modernity, a new universe of material goods and new arenas of public display. Changing social roles amongst these urban classes, particularly women, combined with greater financial and social mobility, consumer confidence, and access to commodities and transnational7 lifestyles—that were previously only within the reach of the elite or those in Western capitalist countries—also had implications on fashionable dress. Alongside an increase in choices with regard to availability of international and national clothing brands, India’s fashion industry also transitioned from being largely export-oriented to focusing on local consumers, and supporting emerging indigenous designers towards establishing a strong Indian design aesthetic.

Despite such dynamism and the fact that New Delhi and Mumbai are now counted amongst the world’s top fashion cities,8 the movement and nature of “fashion” in India, when compared to the global acclaim enjoyed by Indian traditional dress and craft practices, remains a lesser-explored subject. My initial research revealed few academic texts or discussions on the topic. Most twentieth century fashion theory regarded fashion as a Western phenomenon and categorized all other forms of non-Western dress as fixed, non- or anti-fashion (Flugel 1971[1930]; Polhemus and Proctor 1978; Hollander 1994; Lipovetsky 1994; Entwistle 2000; Wilson 2003 [1985] etc.). In addressing such inconsistencies between academic discourse and the everyday existence of fashion, combined with the general predominance of stereotypical viewpoints about Indian dress, this book offers a broad survey of contemporary fashion in India as it relates to the emerging urban classes in the decades following the country’s liberalization phase. Its aim is to highlight the presence and nature of dress innovation in India, especially in the case of women’s attire and its design, and demonstrate that there are other modernities and instances of fashion beyond the viewpoint of American and European fashion history.

Since the majority of the book’s discussion is concerned with current dress practices in India, a key point of focus is inevitably the impact of globalization, along with an exploration of the coexistence of tradition and modernity and the resulting hybridity evident in contemporary fashion. Though such characteristics are broadly similar to the way fashion has come to be shaped in other parts of Asia, what gives Indian fashion its own distinctive nature is its specificity to the local context. This includes references to India’s individual history, the continued influence of nationalist ideals, the revival and use of Indian crafts and textiles, and consideration for the vibrant and ever-evolving traditions in tandem with the socio-cultural changes taking place subsequent to liberalization. In addition to covering these aspects in depth, a central argument presented in this text is that the time period following the economic reforms brought about its own unique circumstances and identity-based anxieties as a result of which India’s globalized middle-class and elite segments once again felt the need for the assertion of a distinct Indian identity, which extended to fashion and dress. Interestingly, this led to the remobilization and reinterpretation of various methods of self-fashioning that saw their roots in the colonial period and Indian nationalism, some of which also reaffirm the lasting influence of Orientalist frameworks. Various strategies of sartorial fusion practiced in response to colonial dress, the nationalist movements and the politics and symbolism of textiles and dress as part of the Swadeshi movement9 continue to resonate in current day constructions of the desi-chic look and related design ideals, and form some of the core concepts within the book.

As its subtitle suggests, the book highlights the innovations inherent in the way women’s traditional clothing has evolved to date and its continued relevance to fashion—from couture to street. The book’s chapters also illustrate various instances where the perceived dichotomy between traditional dress and global fashion has instead led to some very innovative and hybrid sartorial outcomes. As evident in the case of the evolution of the sari, this phenomenon is not new to current times. To support this point, the book highlights some key scenarios from the past century and a half that not only demonstrate this, but as indicated above, also remain central to the way fashion functions in India today.

Terms and definitions

While conducting research on the subject of fashion and dress it is not uncommon to come across significant variations in the way clothing terminology is applied and understood. Hence providing a framework of terms and definitions used throughout this book is a crucial starting point for this chapter. Outlining certain dress and fashion-related terms and their meanings, like costume and traditional [dress], is also necessary as they have frequently been employed [historically] in academic and non-academic texts to include or exclude certain societies and cultures from the phenomenon of fashion. Therefore making them potentially loaded terms.

Dress vs. costume

Throughout this text the term dress is widely used due to its ability to function as a neutral and inclusive term when referring to clothes or garments of all types and styles. This is in keeping with Eicher and Higgins’ definition of dress as an “assemblage of body modifications and body supplements displayed by a person and worn at a particular moment in time” (Eicher and Higgins 1992, cf. Eicher, Evenson and Lutz 2000: 4). Alongside dress, I use the terms clothing and garment/s as they too are similarly universal terms for referring to various styles of dress, single or multiple items and outfits. In comparison, I use the term costume sparingly while discussing contemporary clothing. This is primarily because close attention to the term costume reveals it to be highly problematic due to its usage in reference to “exceptional dress, dress outside the context of everyday life: Halloween costume, masquerade costume, theatre costume” (Baizerman, Eicher and Cerny 2000: 105–6). Hence, making it largely incompatible with the majority of the discussion in this text (barring the segment on film and television). In some cases the term is also used to refer to museum collections and historic repositories of clothing from all cultures (ibid.). Bearing all of these connotations in mind, the term costume, when combined or associated with Indian dress, renders it incapable of being viewed as fashion.

Traditional, ethnic and modern

The complex nature of terms like modern on the one hand, and traditional or ethnic on the other becomes apparent when they are used in reference to dress. This is especially so in the case of most past writings on clothing practices pertaining to non-Western countries, where, for example, when the term traditional was applied to dress it was done so to denote its likeness to fixed costume (Baizerman et al. 2000: 106). Eicher et al. (2000: 45) have found that the term tradition is often used to signify practices that come from the past. Similarly, Edensor (2002) states that traditions are commonly conceived and constructed as being opposed to modern or modernity, and as a result become linked to notions of authenticity and continuity. In other words, traditional dress is regularly viewed as an authentic representation of the past or embedded in ritualized behavior that has been handed down over many generations, which in doing so has remained static or unchanged. The term ethnic, linked to ethnicity, signifies group cohesion, common identity, heritage and cultural background, which includes shared language, dress, manners and lifestyle (Eicher and Sumberg 1995). Through its close association with tradition and overarching Eurocentric frameworks that continue to impact the reception of the term as Other, ethnic is also commonly used in a manner that provokes a romantic, exoticized image.

Edensor challenges popular assumptions linked to such terms through highlighting the need for symbolic cultural elements like traditions and traditional dress to be flexible in order for them to remain relevant over time. Thereby, recognizing traditions as dynamic and dialogic “modern” entities that are “always in the process of being recreated and subject to evaluation in terms of what they bring to a contemporary situation” (Pikering 2001, cf. Edensor 2002: 105). When viewed in this way it is possible to see how traditional dress can and indeed does shift, change and adapt to accommodate new shapes, styles and items from other places and cultures—and in doing so it can be linked to fashion. Recent studies on dress and fashion have contributed to the revaluation of the terms ethnic and traditional especially when applied to non-Western dress. Tarlo (1996), Craik (1994), Cannon (1998) and Maynard (2004) all note the concept of fluidity in traditional and ethnic dress that are subject to the process of fashion change.

In this text I use both terms ethnic...