![]()

CHAPTER 1

SUBJUGATION 800–1200

The Frankish Empire

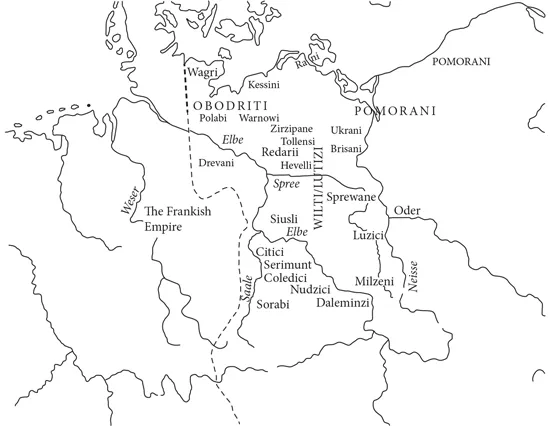

Around 800, the year when Charlemagne was crowned emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, the limits of Slav settlement extended at least as far west as the lower Elbe and the Saale (see Map 1.1). They stretched northwards to a point close to where Kiel now stands, embracing what later became east Holstein. Along this frontier the heathen Slavs faced the Christian forces of the expanding Frankish Empire (Herrmann 1985: 10). The chain of events culminating in this situation leads us back to the decline of the Western Roman Empire. It was this that had first provided the Franks, a Germanic tribe originating in the region of the lower Rhine, with opportunities for expansion. Clovis or Chlodwig (c. 466–511), king of the Salian Franks from 481, succeeded in enlarging his domains to incorporate much of Roman Gaul, and his conversion to Christianity in 496 brought him the assistance of Roman bishops and officials in consolidating his gains. From a small tribal territory a great empire emerged, and throughout the reign of the Merovingian dynasty (c. 500–752) expansion continued (Scheuch 2001: 13).

Map 1.1 Western limits of Wendish settlement c. 800 (shown by a broken line _ _ _ _) and names and locations of main Wendish tribes.

To the east of the Frankish Empire in the early sixth century lay the territory of the heathen Thuringians (Toringi), a Germanic tribe, stretching as far east as the River Saale. Clovis’s four sons continued their father’s policy of expansion and, in alliance with the Saxons, conquered the Thuringians in 531, incorporating their land (Herrmann 1985: 36–7; Köbler 1999: 650; Scheuch 2001: 13). In the following century the Franks encountered the empire of Samo, a state created out of an alliance of Wendish tribes which around 625 had fought successfully against the Avars before coalescing as a political unit. Dagobert, king of the Franks, seeing himself threatened by Samo, embarked on a campaign against him, but suffered defeat at Wogastiburg (location unknown) (Labuda 1949: 23–4, 126–32; Herrmann 1985: 12, 37). It is in the context of Dagobert’s defeat that we encounter the Sorbs, one of the Wendish tribes, and learn the name of their leader Dervanus. In 630 or 631, according to the chronicle of Fredegar, ‘Dervanus too, a leader from the tribe of the Sorbs, who were of the clan of the Slavs and in times past had belonged to the kingdom of the Franks, consigned himself with his followers to the kingdom of Samo (. . . etiam et Dervanus dux gente Surbiorum, que ex genere Sclavinorum erant et ad regnum Francorum iam olim aspecserant, se ad regnum Samonem cum suis tradedit)’ (Fredegar 1888: 155). Samo died in 658. The location of his kingdom is uncertain, but it may have been on the River Morava, on the site of the future Moravia (Magocsi 1993: 8–9).

Fredegar is the earliest source to mention the Sorbs by name and also the earliest record of the name of any of the Wendish tribes in the area which later became Germany (Herrmann 1985: 7). In the scheme of Slavonic tribal nomenclature 630/631 is an early date. The name of the Poles (Poleni), by comparison, is first recorded over 300 years later in the Chronicle of Thietmar (975–1018). It is worth noting that the Surbi in Fredegar’s account are a subgroup of the Sclavini (the same form as that used a 100 years earlier by Jordanes).

Names of Wendish tribes

There are no further seventh-century sources for the history of the Wends. The Merovingian dynasty came to an end in 751 with the death of King Childerich III. In Carolingian times the sources are less elusive, but they still concentrate on alliances and battles, victories, and defeats. Apart from the generic terms Sclavi, Slavi, Winedi, and variants of these, early medieval records contain over sixty other ethnic names denoting the various Wendish tribes in the area to the east of the Frankish Empire. They are located, roughly speaking, between the Elbe and Saale in the west and the Vistula, Bober, and Queis in the east. Possibly out of consideration for modern political sensibilities, it appears to be generally assumed that there was some kind of natural break between the tribes that subsequently came under German control and those subsumed by Poland, but there is no evidence for this. The Poleni (who gave Poland its name) were a land-locked tribe, bounded to the north, between the Oder and the Vistula, by the Pomerani. To the east of the Bober and Queis were the ancestors of today’s Silesians (Dadosani and Slezani).

Many of the Wendish tribes were small and insignificant and most of them were not independent but part of larger ethnic formations. The main significant groupings were as follows, proceeding from the Baltic southwards:

1. The Obodriti. These are first noted in connection with Charlemagne’s Saxon campaign in 781. They were made up of the Wagri (also known as Travjani), who originated in east Holstein, the Polabi, between the Rivers Trave and Elbe, the Warnowi, on the upper Warnow and Mildentz, and the tautonymous Obodriti, located between Wismar Bay and south of Lake Schwerin.

2. The Pomerani between the lower Oder and Vistula.

3. The Velunzani, also called Lutizi. Their German name is Wilzen. They included the Kessini, on the lower Warnow, the Zirzipane, between the Rivers Recknitz, Trebel, and Peene, the Tollensi, to the east and south of the Peene on the Tollense, and the Redarii, to the south and east of Lake Tollense on the upper Havel.

4. The Rujane or Rani. These were the inhabitants of the island of Rügen. As Rugini they are mentioned in a reference datable to around 703 in Bede’s Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum ‘Ecclesiastical History of the English People’, which was completed in 731 (Herrmann 1985: 8).

5. The Ukrani. These were settled on the River Uecker and are first mentioned in 934.

6. The Murizi. Their presence is first recorded in 948, when they were living on the River Müritz.

7. The Linoni. Their main centre was Lenzen in the Altmark.

8. The Drevani (first mentioned in 1004) and the Lipani (first mentioned 956) inhabited land to the west of the lower Elbe. They lost their independence to the Franks around 780 during the reign of Charlemagne.

9. The Hevelli. The name they gave themselves was Stodorani. They inhabited an area to the south of a large expanse of primeval forest separating them from the Obodriti and Velunzani. The Hevelli are first recorded c. 850 as Hehfeldi. Closely associated with them were the Dossani (948), located on the River Dosse; the Zamzizi (948), inhabiting the Ruppin area; the Rezani (948), on the upper Havel; and the Neletici (948), Liezizi (948), and Zemzizi (948), all settled on the lower Havel and the Elbe-Havel pocket, as were also the Smeldingi and Bethenici (c. 850).

10. The Sprewane (948). Their homeland lay to the east of the Hevelli on the lower Dahme and the Spree. To the south of the Hevelli was an area recorded as Ploni. Westwards from here on the right bank of the middle Elbe opposite Magdeburg was the territory of the Marzane (850). The Hevelli, Sprewane, and Marzane were separated from the Sorbian tribes to their south by the wooded and uninhabited hills of the Fläming and other forests.

11. The first reference to the Sorbs (Surbi), dated 630 or 631 (see above), does not locate them, but in the eighth and ninth centuries there are several sources which place them close to the Rivers Elbe, Saale, and Mulde. It is significant that Thietmar (975–1018), who describes the Spree landscape later associated with the Sorbs, does not record the name Sorabi (or anything like it).

12. The northernmost of the tribes who inhabited what later became Lusatia (Ger. Lausitz) were the Lusici (c. 850 as Lunsici). Their homeland became Lower Lusatia (Ger. Niederlausitz). To their south-east were the Milzeni (c. 850 as Milzane) in what eventually became Upper Lusatia (Ger. Oberlausitz). The earliest sources treat both Lusici and Milzeni as independent tribes (Herrmann 1985: 9). Near the Lusici and Milzeni were the Selpoli (948) and the Besunzane (c. 850). On the middle Oder at the end of the eleventh century the presence of the Leubuzzi is recorded. The Licicaviki are mentioned in this area in 929. Other constituents were the Citici, Serimunt, Colodici, Siusler, Daleminzi (or Glomaci), Chutici, Nisane, Plisni, Gera, Puonzowa, Tucharin, Weta, and Neletici (Herrmann 1985: 7–14).

We may assume that the Latin names are mostly based on words applied by the tribes to themselves. Occasionally we are told explicitly that that is so, but, in a few cases, the Franks had a name for a Wendish tribe that differed from that used by the Wends themselves. Thietmar von Merseburg, for example, refers to ‘a district which we call Delemenci, but which the Slavs call Glomaci’ (Thietmar 1992: 61), which establishes that the names Daleminci and Glomaci both refer to the same tribe. Similarly, Stodorane was the Wendish name for the tribe called Hevelli in Germanic (Herrmann 1985: 8–9).

Eighth century

Pippin the Younger (751–768), the first king of the Carolingian dynasty, was at odds with the Saxons, a heathen Germanic people inhabiting the lands to the north-east of the Franks in the same area, broadly speaking, as that known today as Lower Saxony. From here, in the mid-fifth century, the Saxons had begun their participation in invasions and migration to the Romano-Celtic island of Britain, which would one day be England. In Merovingian times (c. 500–752) the Saxons were not only consolidating their position in Britain but also making advances on the Continent, penetrating south into Frankish territory.

Pippin’s son Charles, later known as Charlemagne, succeeded him in 768, and two years later the Frankish diet resolved on war against the heathen Saxons. The Saxon wars were at the centre of Frankish policy for nearly thirty years, during which time the Franks were sometimes allied with the Wends. In 748 several Wendish chieftains had supported Pippin in a campaign against the Saxons (Fredegar 1888: 181; Herrmann 1985: 328, 542). In 782, according to the Frankish chronicler Einhardus, Charlemagne, hearing that the Sorbs, ‘Slavs who inhabit the plains between the Elbe and the Saale’, had carried out raids into the Saxon and Thuringian lands, ordered his officers ‘to punish the insolence of the restive Slavs as quickly as possible’. No sooner had they entered Saxon territory to carry out this task, however, than they heard that the Saxons were arming for war against them. ‘So they gave up the march against the Slavs and set out with troops of the East Franks for the place where the Saxons were said to have assembled’ (Annales 1895: 61).

In 789 Charlemagne embarked on his first campaign against another Wendish tribe, the Wilti, whose great army also included Saxons, Friesians, Sorbs, and Obodriti. They were, nevertheless, no match for the Franks. Their leader, Dragavit, was obliged to surrender hostages and swear fealty to Charlemagne. Although alliances were made and broken without scruple, the Franks were steadfast in their main objective of taming the Saxons, and in 795, supported by the Obodriti prince Witzan, Charlemagne opened a new offensive against them. Crossing the Elbe, however, Witzan was ambushed by the Saxons and killed. He was succeeded by Thrasco, who three years later avenged Witzan’s death. Standing fast in the Obodriti alliance with Charlemagne, Thrasco in 798, in a combined operation with Frankish forces, triumphed over the Saxons at Suentanafeld (near Bornhöved in Holstein) (Herrmann 1985: 328).

Ninth century

Thrasco needed Charlemagne’s backing not only in hostilities against the Wilti but also to bolster his own position among the Obodriti. He appeared before Charlemagne in 804 at Hollenstedt, south of Harburg, whence the Franks were launching one of their last campaigns against the Saxons, presented gifts, and was confirmed by him as king of the Obodriti (Herrmann 1985: 328–9). For their services as the most faithful allies of the Franks in the Saxon wars, the Obodriti were rewarded with the land along the northern Elbe, including the area where Hamburg would later stand, from which Charlemagne had expelled most of the Nordalbing Saxons. The Obodriti thereby became a buffer between the Carolingian and Danish Empires. The Danes had been supporters of the Saxons and so now viewed the Obodriti with belligerence. In 808 Göttrick, king of the Danes, marched into Obodriti territory in alliance with the Wilti, the traditional enemies of the Obodriti. In the ensuing hostilities the Obodriti had great difficulty in holding their own, even with Frankish support. Thrasco’s personal position was now precarious, but in 809, with the support of his old enemies the Saxons, he attacked the Wilti, devastated their settlements, and returned home victorious, laden with booty. He then attacked the Smeldingi (a subgroup of the Hevelli), captured their capital, and compelled everyone to accept his sway. Now at the height of his power, Thrasco was taken unawares by the Danes in Reric and assassinated. His people, the Obodriti, apparently because they had failed to give the protection expected of a buffer, were now deprived of their Nordalbing lands. The Franks tried another defensive expedient, establishing a Limes Saxoniae, a protective band of territory between Lauenburg and the Kiel Förde (Herrmann 1985: 329).

Until 800 (the year of Charlemagne’s coronation) the Saxons had maintained their independence, but in the first part of the ninth century they were finally subjugated by the Franks. Having resolved their Saxon problem, the Franks no longer needed their alliance with the Sorbs, who were now merely standing in the way of their expansion, so in 806 the Sorbs became the victims of Frankish aggression:

And thereupon coming to Aachen a few days later he sent his son Karl with an army into the land of the Slavs that are called Sorabi, who are situated on the River Elbe. In this expedition Miliduoch the leader of the Slavs was slain, and two strongholds were built by the army, one on the bank of the River Saale and the other near the River Elbe.

(Annales 1895: 121)

Miliduch, who in another source is described as ‘a proud king who was reigning among the Sorbs’ (rex superbus, qui regnabat in Siurbis), is the second individual in Sorbian history to be identified by name (the first was Dervanus) and the first recorded as having fallen in battle. That is enough to ensure him a place in the encyclopaedias, though nothing else is known about him (SSS, s.v. Miliduch).

In the last years of Charlemagne’s reign (died 814), the Franks were gaining a kind of control over all the Wends to their east. In his biography of Charlemagne, in a passage relating to around the year 806, Einhard claims:

Thereafter he tamed (so that he might make them pay tribute) all the barbarian and savage peoples who are located between the River Rhine, the River Vistula, the sea, and the Danube, and inhabit Germania, who in language are fairly similar, but in customs and dress are very dissimilar. The most important among them are the Weletabi, the Sorabi, the Abodriti, and the Boemani. Against these he waged war; the others, who were far more numerous, submitted to him voluntarily.

(Einhardi Vita 1911: 18)

Having installed an Elbe crossing and fortress at Höbeck (Hohbuoki) opposite Lenzen in 789, Charlemagne thought he had established Frankish authority, but in 810 the Wilti showed that they thought otherwise by destroying it. Two years later they were again defeated by a superior Frankish army and forced to hand over hostages (Herrmann 1985: 329).

The Limes Sorabicus

The emperor’s representatives on the outskirts of the Frankish Empire had special responsibilities for defence. For this purpose the Frankish Mark ‘march’ was devised, a border-territory constituting a political and military unit ruled by a Graf ‘count’. Marken ‘marches’ were set up at several points on the empire’s frontiers. They were a way of streamlining the defence of the state’s outer limits and in later centuries they provided bases for the formation of new German principalities. Just as the German word Mark may mean either ‘frontier’ or ‘border-territory, march’, so each of the Latin equivalents marchia and limes in medieval German sources has both senses. Marken as administrative units along the Saale and Elbe, where Frankish and Wendish lands met, were first created in the ninth century.

A capitulary of Charlemagne issued in Diedenhofen (Thionville) in 805 specified the points at which trading with the Wends and Avars was permitted along the Franks’ eastern limits, a line stretching from Bardewik on the lower Elbe to Lauriacum (now Lorch) on the Danube. It was once erroneously thought that the capitulary in question used the term limes sorabicus ‘Sorbian frontier’ to refer to this eastern boundary, but in fact the term is not actually found in this source. It does, however, occur later in the Annales Fuldenses under the years 849, 858, 873, and 880, but here it has the sense ‘borderland, march’ not ‘frontier’. This Limes Sorabicus was a Sorbian march, whose ruler (the Markgraf ‘margrave’) was simultaneously Duke of Thuringia. The ruler of this Sorbische Mark (as it is known in German historiography) in the years 847–873 was Takulf, Duke of the Sorbian March (dux Sorabici limitis), and after his death Ratulf (who is mentioned only once, in 874). He was followed from 880 by Boppo (or Poppo) (SSS, s.v. marchia, limes sorabicus).

Louis the Pious (r. 814–840)

Towards the end of Charlemagne’s life, once the Saxons had been subdued, the Frankish policy of expansion was gradually replaced by one of consolidation (Scheuch 2001: 18). His son and successor Louis the Pious, however, was determined to maintain the empire’s influence beyond the Elbe. He exploited intrigues and rivalries among the Obodriti aristocracy. Following the assassination of Thrasco in 809, Charlemagne had transferred the royal power not to Thrasco’s son Cedragus, who was still a child, but to Slawomir. In 817, three years into his reign, Louis the Pious, realized that he could use Cedragus, who was now a man, to manipulate Slawomir. He ordered Slawomir to share royal power with Cedragus, but Slawomir would not comply. Instead, he showed his resentment by allying himself to the Franks’ most bitter enemies, the Danes, and with them began military action in the north-Elbe region...