![]()

1

Śītalā, the Cold Mother

Indian medical culture depends on the knowledge and practices of physicians, surgeons, ritualists, healers, magicians, astrologers, ascetics, yogis, fakirs, etc. These specialists derive their authority from education, consortium, lineage, or divine designation. Alongside, there exists a series of healing measures that do not require the skills of specialized personnel. Such is the case of rites informed by faith (śraddhā), belief (viśvāsa) and devotion (bhakti). Within this context, an unsystematic, and often undocumented, healing culture has emerged. Rather than on knowledge, authority and tradition, this relies on the capacity of devotees to move powerful and holistic healers: the gods. One such deity is the goddess Śītalā.

The name śītalā is a tatsama śabda (identical loanword) derived from the Sanskrit root śīta, ‘cold’. It can be a noun (‘cold’, ‘coldness’) or an adjective (‘cold’, ‘cool’, ‘cooling’, ‘refreshing’, ‘calm’, ‘gentle’, ‘mild’, ‘free from passion’). The goddess is ‘Coldness’, or the ‘Cold [Lady]’. Śītalā, who is principally a women’s goddess, is visualized as a mother (mā, mātā) who protects children from paediatric ailments, notably exanthemata. She is also a fertility goddess, who helps women in finding good husbands and conceiving healthy sons. Her auspicious presence ensures the wellbeing of the family, and protects sources of livelihood. Being cold, Śītalā is summoned to ensure regular refreshing rains, and to prevent famines, droughts and cattle diseases. The worship of Śītalā is not just functional to protection. It has served for centuries to learning and disseminating basic hygienic norms for the wellbeing of the household.

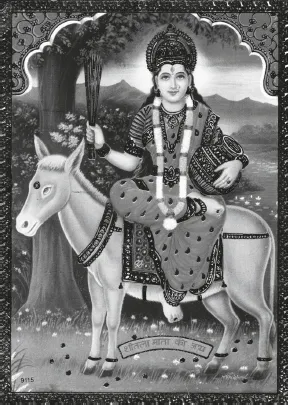

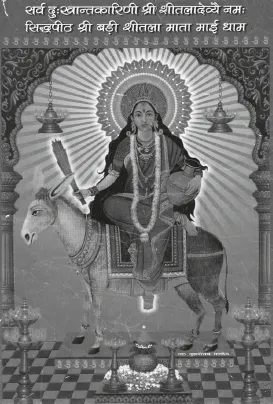

Śītalā Devī is easily distinguishable. According to a consolidated iconography, she sits side-saddle on an ass, holds a broom and carries in the crook of her left arm a big pitcher. Textual sources agree with a standard description: the three-eyed goddess is a white-complexioned naked (digambara, ‘sky-clad’) young lady with long black dishevelled hair and a winnowing basket on her head. All these objects bear witness to her skills in managing and controlling diseases. The vessel contains cold healing water. With the broom the goddess wipes ‘dirt’ away. The winnower, a reminder of her agricultural origin, is used to throw fresh air at those burning with fevers. In modern and contemporary renditions, Śītalā wears a red sari, is heavily bejewelled and is adorned with a gold tiara.1

FIGURE 1.1 Śītalā Mātā, postcard (author’s collection).

The description is that of a reassuring goddess. Yet from the eighteenth century, Śītalā begins to be represented consistently as a capricious, dangerous and disease-inflicting deity. It is the beginning of the myth of the ‘goddess of smallpox’. Stories of a powerful yet lesser goddess of Indian peasantry originally emerge in a minor chapter of the Bengali premodern maṅgalkāvyas (B. auspicious poems). In the Śītalāmaṅgalkāvyas, Śītalā is an intimidating presence who distributes infected pulses in village markets, or sends hordes of disease-demons, thus causing outbreaks of smallpox and other contagious illnesses. Only when properly worshipped does she agree to heal her victims. This mythology has been enthusiastically received. Unfamiliar to the rest of India, it has been celebrated by Bengali intellectuals as genuine folk poetry, and has informed virtually all scholarly works on the goddess.

In this book, I argue that, to appreciate the place of Śītalā in Indian culture, one should study her from a trans-regional perspective. It has been posited that there exist two isoglosses: the Bengali disease-inflicting goddess, and the north-western protector of children (Wadley 1980: 35). I do not agree. The vindictive goddess of maṅgal poems is an exception confined to a small section of a regional literary genre. Bengalis, as other Indians, do not fear Śītalā, whom they worship as a protector and an auspicious presence.

Giving a comprehensive portrayal of Śītalā, however, is a gigantic task. The goddess has adapted variously to āñcalik culture. Sanskrit and vernacular texts, written and oral alike, describe her as a benevolent mother, a riverine goddess, a murderous hag, a tantric Śakti, a wise Brahman elderly woman, a sweeper, a washer-lady and a queen/princess. She has been associated with characters of the Rāmāyaṇa and the Mahābhārata, and is worshipped as a form of pan-Hindu (Kālarātrī, Gaṅgā, Sarasvatī, Parvatī, Lakṣmī, Vaiṣṇo Devī, Durgā) or regional (Masānī, Manasā, Olā Bibi, Ṣaṣṭhī, various Caṇḍīs and the seven sister) goddesses. Her titles are generally those of a protective mother.2 Other appellatives point at royalty and auspiciousness: Bhagavatī, Ṭhākurāni, Maṅgalā (Auspicious One), Jāgatrānī (Queen of the World), Dayāmāyī (Compassionate One) and Karuṇamāyī (Merciful One). Only in the ŚMKs, she is the threatening Vasanta Rāy (Queen of the Spring, i.e. of the pox season), Rog Rāy (Queen of Fevers) and Rogeśvarī (Lord of Diseases).

Ritual culture too is not uniform. Śītalā is offered stale, cooling and refreshing vegetarian edibles, but also the blood and flesh of sacrificed animals. Her pūjārīs (votaries) are Brahmans but also members of low occupational classes. She is celebrated by the working class, the peasantry, middle and upper classes and royalty in open-air shrines (thān) and majestic temples (mandir). She has a standard anthropomorphic iconography, but is believed to inhabit stones, ponds, rivers, terracotta animals and various trees. She is the rain and, more generally, the waters. Devotees have darśana (vision) of Śītalā when worshipping her mūrtis and pratimās (icons). Alternatively, the goddess manifests on occasion of intense meditation, austerities, in dreams and during phenomena of devotional possession.

Within such apparently chaotic landscape, Śītalā has continued to give voice to the same anxiety: protection from disease. The following song, collected by Dr Robert Pringle, Superintendent General of Vaccination in the North-western Provinces, illustrates the nature of the goddess in a historical period marked by virulent smallpox epidemics:

Visit, oh! Seetla, this secluded dwelling; stand at the door, / And give this child the gift of health. / Much have we worshipped thee for its sake before its birth: / We have worshipped thee at Pryag (Allahabad) and Juggernauth [in Puri], / And bathed in the sacred Ganges at Hurdwar [Haridwar], / And we have made obeisance at all thy shrines. / We will paint thy face with ‘roree’ [H. rorī, red clay], and pour into thy lap sweet smelling spices. / Then go, and swing thyself happy on thine own neem tree, / That so all in this house may be happy likewise. (Pringle 1885: 740)

Lexicographers confirm the protective nature of the goddess, and report that Śītalā is adhiṣṭhātrī (Skt. adhiṣṭatr̥: presider, controller) (Nā 1245; BaŚ 2029) and, more specifically, vasantavisphoṭakāderadhiṣṭātrī (‘She who controls the spring [fever] and the pox’) (ŚKD 346, vol. 5). Śītalā is the goddess who hinders disease (H. ‘rog nivarāk devī’) (Giri et al. n.d.: 75). She is a remover and a destroyer (haranī) of illness, a skill she derives from her being actually and intrinsically cold (Wadley 1980: 35; Filippi 2002: 196). In particular, she controls and heals from imbalances that express themselves through unnatural states of hotness (e.g. disease, misfortune and environmental catastrophes). Interpreting her name as a euphemism, ‘an attempt to ward off the goddess’s fire as she rages through the Bengali countryside […]’ (Dimock 1982: 184; see also Kolenda 1982: 236) is inaccurate.3 Though Śītalā can be angry and seek revenge, nobody in India would call her masūrikā or visphoṭaka devī. This is no pedantic remark.

The label ‘smallpox goddess’ – or ‘disease goddess’ – suggests identity with, or dependency upon, illness. In fact, Śītalā is not the deification of smallpox. Poxes exist independently, and used to be associated with the coming of the spring season (Skt. vasanta) (cf. RSC xciv). North Indian languages bear witness to this coincidence, as smallpox is popularly known as vasanta roga (spring fever). Alternatively, the disease is called with names evocative of its most evident symptoms, i.e. pustules. Smallpox is ‘lentil’ (H. and B. masūr); ‘bursting’ (H. sphoṭ; B. sphōṭak/phuskuḍi); ‘itching’ (H. khasrā); ‘pustule’ (H. goṭī; B. guṭikā); and ‘pearl’ (H. moṭī; B. muktā). But the symptoms of smallpox are not just the ulceration of the skin and the appearance of boils and vesicles.4 The shivering of a smallpox victim is a powerful sign, and a visual reminder, of its cure. Fevers are thus called ṭhanḍī, śīt, śītalī or śītalikā (lit. ‘coolness’). Such names provide not just an indication of the most obvious therapeutic course, but are evocative of the much-needed (i.e. auspicious) visitation of the Cold Lady.5 Not by chance is the goddess called sarvarogahāriṇī (B. ‘the destroyer of all diseases’) and vasantarogahariṇī (‘the destroyer of the spring disease’ – i.e. smallpox) (Bhaṭṭācārya 1997: 150–1).

FIGURE 1.2 Śītalā Mātā, front page of vintage calendar (author’s collection). The invocation reads: sarva duḥkhāntakāriṇī śrī śītalādevyai namaḥ (Skt. ‘Obeisance to the goddess Śītalā, the destroyer of all sufferings’).

Bursts of v...